- People with diabetes should be seen as individuals with a condition that has medical, personal and social consequences, instead of being passive recipients of health care.

- The optimal management of diabetes occurs when the multidisciplinary diabetes care team actively involves the person with diabetes as an equal partner in their care.

- Life-threatening diabetes emergencies, such as diabetic ketoacidosis, should be effectively managed, and attention paid to prevention.

- Acute symptoms of hyperglycemia need to be addressed by careful lifestyle and pharmacologic management.

- Much of diabetes management is focused on reducing the risk of long-term complications through screening and supporting achievement of improved glycemic control and cardiovascular risk factor management.

- The time of diagnosis is a key milestone in the management of diabetes, when education, support and treatment are needed.

- Regular lifelong contact between the person with diabetes and their health care team is essential in order to support them to cope with the demands of a complex condition which changes throughout life.

- Diabetic complications should be managed effectively, if and when they present, to reduce morbidity.

Introduction

Diabetes is a lifelong condition that is, for the majority, currently incurable. It is associated with premature mortality and morbidity from an increased prevalence of cardiovascular disease and microvascular complications affecting the kidney, nerve and eye [1,2]. High-quality randomized trials have shown that improving glycemic control is associated with a reduction in microvascular complications [3–5] while a multifaceted approach to cardiovascular risk factors will reduce cardiovascular morbidity and mortality [6].

The person living with diabetes will spend the vast majority of their time managing their diabetes and only an estimated 1% of their time in contact with health care professionals. Therefore, the person with diabetes needs to be supported to take upon themselves much of the responsibility for the management of their diabetes. Given the central role of the person with diabetes and the relatively little contact with health care professionals, it is important that the purposes of the consultation or other contacts with the diabetes health care team are well defined and their aims are made clear so that the patient derives the maximum benefit from the time spent with their diabetes health care team, whether this is in a hospital or primary care setting. As well as the clinic visit, diabetes care may also be through phone or email contact or through educational sessions outside a traditional clinic setting.

This chapter provides an overview of the aims and philosophy of diabetes care. Separate aspects of care are covered in greater detail in subsequent chapters. The aims of diabetes care and management are fourfold. Life-threatening diabetes emergencies, such as diabetic ketoacidosis or severe hypoglycemia, should be managed effectively including preventative measures. The acute manifestations of hyperglycemia, such as polyuria and polydipsia, need to be addressed. In practice, these occupy only a minority of the work undertaken by diabetes health care professionals. Much of the focus of care is therefore directed towards minimizing the long-term complications through screening and working together with the person with diabetes to support improved glycemic control and cardiovascular risk factor management. This provides a challenge for the diabetes team because people often have no symptoms at the time of care and yet are asked to make lifestyle changes and take medications that may place a considerable burden on that individual. It is also important that clinicians bear in mind the fourth aim of care which is to avoid iatrogenic side effects, such as hypoglycemia. Involvement of the person with diabetes in this care planning is paramount to success.

St. Vincent’s Declaration

During the 1980s, there was a transformation in the widely held perceptions of the roles of people with diabetes and philosophy of care. Instead of being viewed as passive recipients of health care, there was an increasing recognition that people with diabetes were individuals with a condition that has medical, personal and social consequences. During this time, there was an increasing awareness and acceptance of the concept that each person with diabetes should accept part of the responsibility for their treatment and act as equal partners with health care professionals. In response to this paradigm shift, representatives of government health departments and diabetes organizations from all European countries met with diabetes experts under the auspices of the Regional Offices of the World Health Organization (WHO) and the International Diabetes Federation (IDF) in the hillside town of St. Vincent, Italy, October 10–12, 1989. They unanimously agreed upon a series of recommendations for diabetes care and urged that action should be taken in all countries throughout Europe to implement them [7]. Since this time, this philosophy of partnership between people with diabetes and health care professionals has been adopted within individual nation’s strategies to improve the quality of diabetes care.

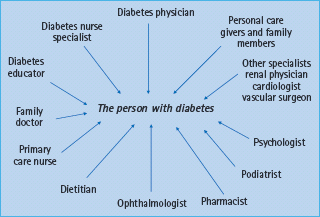

The diabetes care team

The diabetes care team involves a multidisciplinary group of health care professionals who are available to support the person with diabetes (Figure 20.1). A key component of diabetes care is to ensure that the individual with diabetes is at the center of the provision of care. This means that the person with diabetes should work together with the health care professionals as an equal member of the diabetes care team. This relationship should provide the information, advice, and education to support the empowerment of the individual with diabetes to enable them to take control of their condition and ensures that care offered is made appropriate for the individual and their circumstances.

Figure 20.1 The multidisciplinary group of health care professionals who are available to support the person with diabetes.

- Elaborate, initiate and evaluate comprehensive programs for detection and control of diabetes and of its complications with self-care and community support as major components

- Raise awareness in the population and among health care professionals of the present opportunities and the future needs for prevention of the complications of diabetes and of diabetes itself

- Organize training and teaching in diabetes management and care for people of all ages with diabetes, for their families, friends and working associates and for the health care team

- Ensure that care for children with diabetes is provided by individuals and teams specialized both in the management of diabetes and of children, and that families with a child with diabetes obtain the necessary social, economic and emotional support

- Reinforce existing centres of excellence in diabetes care, education and research

- Create new centers where the need and potential exist

- Promote independence, equity and self-sufficiency for all people with diabetes, children, adolescents, those in the working years of life and the elderly

- Remove hindrances to the fullest possible integration of people with diabetes into society

- Implement effective measures for the prevention of costly complications:

- Reduce new blindness caused by diabetes by one-third or more

- Reduce numbers of people entering end-stage renal failure by at least one-third

- Reduce by half the rate of limb amputations

- Cut morbidity and mortality from coronary heart disease by vigorous programs of risk factor reduction

- Achieve pregnancy outcomes in women with diabetes that approximate that of women without diabetes

- Reduce new blindness caused by diabetes by one-third or more

- Establish monitoring and control systems using state-of-the-art information technology for quality assurance of diabetes health care provision and for laboratory and technical procedures in diabetes diagnosis, treatment and self-management

- Promote European and international collaboration in programs of diabetes research and development through national, regional and World Health Organization (WHO) agencies and in active partnership with the person with diabetes and diabetes organizations

- Take urgent action in the spirit of the WHO program, “Health for All,” to establish joint machinery between WHO and International Diabetes Federation European Region to initiate, accelerate and facilitate the implementation of these recommendations

The large number of health professionals involved in the diabetes care team means that the roles and responsibilities of all must be clearly presented and agreed. It is often helpful for the person with diabetes if the key members of the diabetes care team are identified, as they will have more contact with some health care staff than others.

Most routine diabetes care takes place in a primary care setting but some people with diabetes with additional or complex needs will require management and support in a specialist setting for some or all of their care [8]. The diabetes physician usually takes the overall responsibility for the diabetes medical care but other specialists may be involved, for example an ophthalmologist may be needed to examine the eyes carefully and treat diabetic retinopathy if present. Diabetes care is multidisciplinary, involving doctors, nurses and many allied health care professionals whose responsibility is to support the person living with diabetes in the management of their condition. A close collaboration between primary and secondary health care professionals and among specialists is needed to ensure that all involved are aware of the issues that are relevant to the individual with diabetes and that care is integrated and coordinated across the wide range of disciplines involved. Placing the person with diabetes at the center of care is likely to facilitate collaboration.

Given the chronic nature of diabetes, continuity of care is essential. Ideally, this should be provided by the same doctors and nurses at each visit, but where this is not possible, the health care team should have access to previous records so that they are fully aware of the medical history and background of the person with diabetes. In some low and middle income countries, where medical records are focused on the acute care of infectious diseases, this is particularly challenging [9].

With the involvement of the person with diabetes in the diabetes team come a number of responsibilities for that individual. The task of implementing the day-to-day management plan lies with the person with diabetes and sometimes it can be difficult for health care professionals to accept this. It must be understood that managing diabetes is challenging, but the diabetes care team should be there to support the person through their experiences with their condition. Adolescence can be particularly challenging as this period of the person’s life coincides with a time of change when experimentation and adaptation by the adolescent are to be expected (see Chapter 52).

Improving the outcome of the consultation

The time that a person with diabetes spends with a health care professional is limited and should be used as effectively as possible. It is important that both the person with diabetes and the health care professional prepare for the clinic visit. In the UK, the Department of Health has provided literature entitled Questions to Ask, which provides guidance about the questions a person with diabetes should ask during a consultation to maximize the benefit from the visit to their health care team [10].

Before your appointment

Write down your two or three most important questions

List or bring all your medicines and pills – including vitamins and supplements

Write down details of your symptoms, including when they started and what makes them better or worse

Ask your hospital or surgery for an interpreter or communication support if needed

Ask a friend or family member to come with you, if you like

During your appointment

Don’t be afraid to ask if you don’t understand. For example, “Can you say that again? I still don’t understand”

If you don’t understand any words, ask for them to be written down and explained

Write things down, or ask a family member or friend to take notes

Before you leave your appointment check that:

You’ve covered everything on your list

You understand, for example “Can I just check I understood what you said?”

You know what should happen next – and when. Write it down

Ask who to contact if you have any more problems or questions

Ask about support groups and where to go for reliable information

Ask for copies of letters written about you – you are entitled to see these

After your appointment, don’t forget to:

Write down what you discussed and what happens next. Keep your notes

Book any tests that you can and put the dates in your diary

Ask what will happen if you are not sent your appointment details

“Can I have the results of any tests?” (If you don’t get the results when you expect – ask for them.) Ask what the results mean

The consultation or education program should lead the person with diabetes to gain a clear understanding of their condition. This can only be achieved effectively when professionals and people with diabetes are enabled to work together. The interaction should not be seen as an opportunity for the health care profession to “give care” to the patient, but an opportunity for equal involvement in decision-making and care.

People with diabetes should be encouraged to ask questions to check knowledge and further explanation and literature may be needed. It is good practice to provide the person with diabetes with copies of any letters written about them [11,12]. Questions about their treatment should be encouraged and they should be aware of what will happen next, including any requirement for further investigation. Regular review of management plans through joint dialogue, listening, discussion and decision-making between the person with diabetes and health care professional, sometimes known as care planning, is the key to enhancing relationships and partnership working [13]. Contact details should be made available so the individual with diabetes knows where to seek help if further questions arise.

Following diagnosis

The period following the diagnosis of diabetes is crucial for the long-term management of diabetes. A huge amount of information and skills need to be assimilated by the person with diabetes at a time when they may be in denial or angry with the diagnosis [14]. Considerable skill is therefore needed to support them at this time. The diabetes team should perform a medical examination (usually the physician) and develop a program of care with the person with diabetes. It is important that this is individualized so that it suits the particular person with diabetes and should include treatment-oriented goals.

Issues relating to diagnosis

The diagnosis of diabetes is based on the finding of one or more glucose values above internationally agreed values (see Chapter 2) [15]. Usually, a diagnosis has been made prior to referral to the diabetes clinic but this is not always the case. In the absence of symptoms, individuals should have two values above the diagnostic criteria. Where there is diagnostic doubt, the 75-g oral glucose tolerance test is the investigation of choice but there is ongoing discussion about the use of glycated hemoglobin as a diagnostic test [16].

While the diagnosis of diabetes has frequently been made prior to referral, advice may be required to determine the type of diabetes as the distinction is not always as clear as may be expected. When a young preschool child develops weight loss, polyuria, polydipsia and ketoacidosis over a short period of time, the diagnosis is obviously type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM). In contrast, if an asymptomatic elderly overweight individual is found to be hyperglycemic, the diagnosis is type 2 diabetes (T2DM) (see Chapter 19). These presentations lie at two ends of a spectrum, and the diagnosis of the type of diabetes may be less clear when the onset occurs in the thirties in an overweight adult who is found to have islet cell antibodies. Diabetes health care professionals should also be alert to the possibility of monogenic causes of diabetes (see Chapter 15).

Although a precise diagnosis may not be needed from the outset, an early decision should be made about the necessity for insulin therapy (see Chapter 19). While there are clinical features that suggest the type of diabetes, time is often a useful diagnostic tool to determine whether the person with diabetes requires insulin.

Diabetes education

A key component of the empowerment of the person with diabetes is the provision of diabetes education (see Chapter 21) [17]. This information should be provided in a patient-centered manner as it is retained more effectively when delivered in this way. Education may be provided individually or in a group setting.

It is essential that the person with diabetes understands their diabetes and develops the skills and competencies required to take control of their condition as well as possible if they are going to be an effective partner in the diabetes care team.

People with newly diagnosed diabetes should have the chance to speak with a diabetes specialist nurse (or practice nurse) who can explain what diabetes is [18]. This will provide an opportunity to discuss the treatment and goals as well as providing a practical demonstration of any equipment required to manage the diabetes such as blood glucose meters or insulin devices. The importance of ketones testing for those with T1DM should be explained. When self-monitoring of blood glucose has been advocated, it is essential that the person with diabetes knows how to interpret the results and what action is required in response to the treatment.

A qualified dietitian should provide advice about how to manage the relationships between food, activity and treatment (see Chapter 22). Where necessary, they should explain about the links between diabetes and diet and the benefits of a healthy diet, exercise and good diabetes control. As an essential member of an effective clinical care team, a diabetes specialist nurse or practice nurse often has a role in providing dietary advice together with relevant literature [18].

The social effects of diabetes should be discussed, as they may relate to employment, insurance or driving (see Chapter 24). Some countries require individuals with diabetes to inform the appropriate licensing authorities. Advice about diabetes and foot care should also be given (see Chapter 44).

Although education is essential following diagnosis, it is important to appreciate that this is a lifelong process that should take into account recent advances in medical science and changes in circumstances of the person with diabetes [17].

The best measure of successful education may not be simply that someone knows more, but rather that they behave differently. The simple provision of knowledge by itself is often insufficient to influence behavioral change. This can be a particular challenge for the person with T2DM who may have been asymptomatic prior to diagnosis. High demands are placed on the person with diabetes regardless of the type of diabetes, especially when the benefits are not immediate, may only accrue with time and even then may not be appreciated. The individual with diabetes needs to gain an understanding that improved glycemic control can help in preventing the complications of diabetes, such as a myocardial infarction or proliferative retinopathy, even though they may have never experienced these conditions.

The diagnosis of diabetes may provoke a grief reaction and support is needed from the diabetes team to help person with diabetes through this. Engagement is needed to help the person with diabetes come to terms with their diabetes and take control rather than being left with the feeling that their diabetes or their health care team is taking control of them. For some it may take a very long time to accept their diabetes and the demands this places on their life. Therefore, emotional and psychological support and techniques need to be available in the long term.

People with newly diagnosed diabetes often want to speak with others who have diabetes who have had similar experiences while developing diabetes. Many countries have diabetes-related charities that can provide this support and it is therefore important that the information given includes local centers or patient support groups.

The clinic visit

The diabetes team needs to work to together with the person with diabetes to review the program of care including the management goals and targets at each visit [19]. It is important that the person with diabetes shares in any decisions about treatment or care as this improves the chance of jointly agreed goals being adopted following the consultation. A family member, friend or carer should be encouraged to attend the clinic to help them stay abreast of developments in diabetes care and help the person with diabetes make informed judgments about diabetes care.

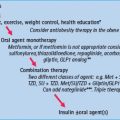

An important goal of diabetes management is to prevent the microvascular and macrovascular complications of diabetes without inducing iatrogenic side effects. This involves active management of hyperglycemia together with a multifaceted approach targeting other cardiovascular risk factors.

Glycemic management

Enquiries and discussions should be made about hyperglycemic symptoms, problems with medications, including issues relating to injections, hypoglycemia and self-monitoring of blood glucose.

Hyperglycemic symptoms

Symptoms relating to hyperglycemia usually occur when the blood glucose rises above the renal threshold leading to an osmotic diuresis. Polyuria, particularly at night, polydipsia and tiredness may ensure. General malaise may also occur and is not always ascribed to the hyperglycemia.

Medications

The diabetes care team is responsible for ensuring that the person with diabetes has access to the medication and equipment necessary for diabetes control. In many countries this is available free or at a reduced rate; many people with diabetes may be unaware of this and timely advice may alleviate some of the anxieties about the cost of diabetes.

Oral hypoglycemic drugs

Each of the oral hypoglycemic drugs has its strengths and profile of side effects (see Chapter 29) and these should be discussed. Strategies should be devised to maximize the tolerability of diabetes medications. For example, the timing of metformin in relationship to meals, or the use of long-acting preparations, may reduce the risk of gastrointestinal upset. Where treatments are not being tolerated, these may need to be changed in order to facilitate improved concordance with the regimen. Another example is the need to discuss the risks of hypoglycemia with sulfonylureas.

Insulin

Insulin therapy is complex: it must be given by self-injection or pump and there is considerable variation in the doses, regimens and devices available. It is important that during the clinic visit the individual has an opportunity to discuss injection technique and any difficulties with injection sites, which should be examined at least annually. Information about the appropriate storage of insulin and safe disposal of sharps (needles) is needed.

The most common side effects of insulin are hypoglycemia and weight gain (see Chapter 27). In addition to these, there are a number of other issues that should be addressed including injection site problems, such as lipohypertrophy, and device problems.

Assessment of glucose control

Supporting the person with diabetes to achieve excellent glycemic control is an essential component of diabetes care. The methods of assessing glucose control essentially involve short-term measures such as self-monitoring of blood glucose and long-term measures such as glycated hemoglobin (see Chapter 25). Not all those with diabetes will undertake self-monitoring of blood glucose, but when they do it is incumbent on the health care professional to discuss the findings with the person with diabetes and how these will affect future management. The glycated hemoglobin provides a further measure of the adequacy of glycemic control and sometimes there may be a discrepancy between this measure and self-monitored blood glucose. It is important to explore the reasons that underlie the differences, which may range from biologic issues such as genetically determined rates of glycation, through to inappropriately timed glucose readings to fabricated results. A pristine sheet (with no blood stains from fingersticks) and with the use of a single pen color may be a clue to the latter. The use of computers and the ability to download results may help to observe patterns of hyperglycemia, although it is important to make sure that the meter has not been shared.

It is clearly important that people with diabetes are encouraged to tell the truth. Sometimes clinicians can appear judgmental which may result in people with diabetes falsifying their results because they are scared. They can feel as if some clinicians are headteachers and they do not want to be reprimanded. It is understandable why someone would not put themselves through that if they did not have to. It is better to break down these barriers and to build a relationship whereby the person with diabetes feels that it does not benefit them to lie, and that the health care professional is there to support, not to judge.

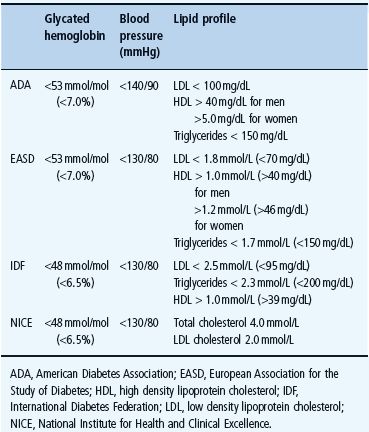

Table 20.1 Glycemic and cardiovascular risk factor targets [20–22,38].

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree