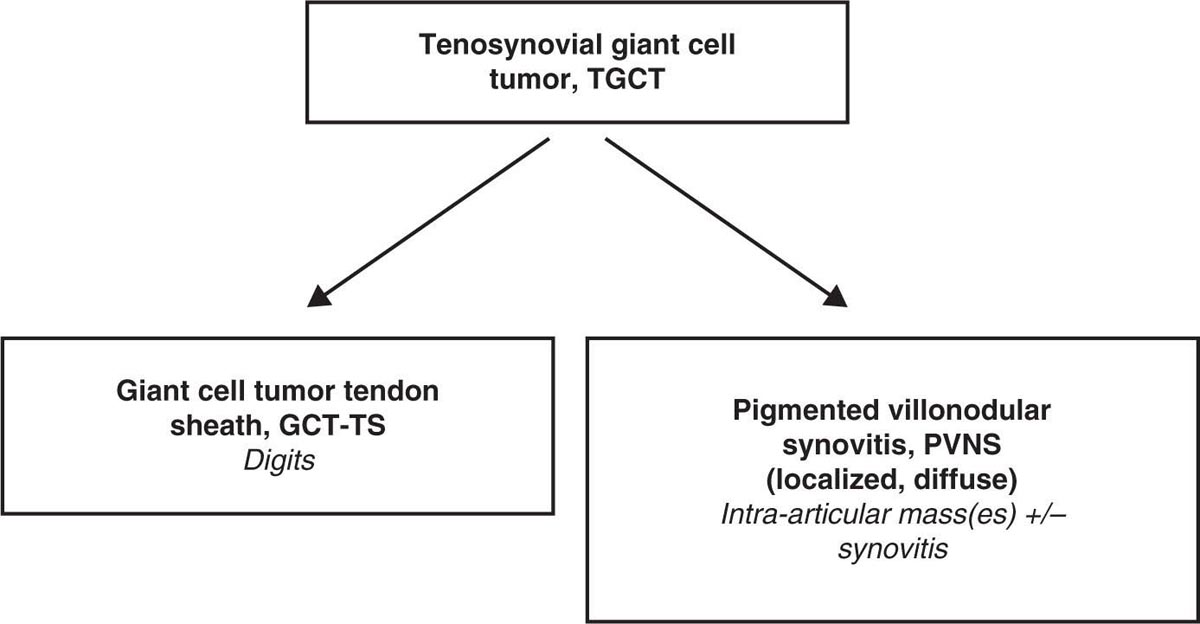

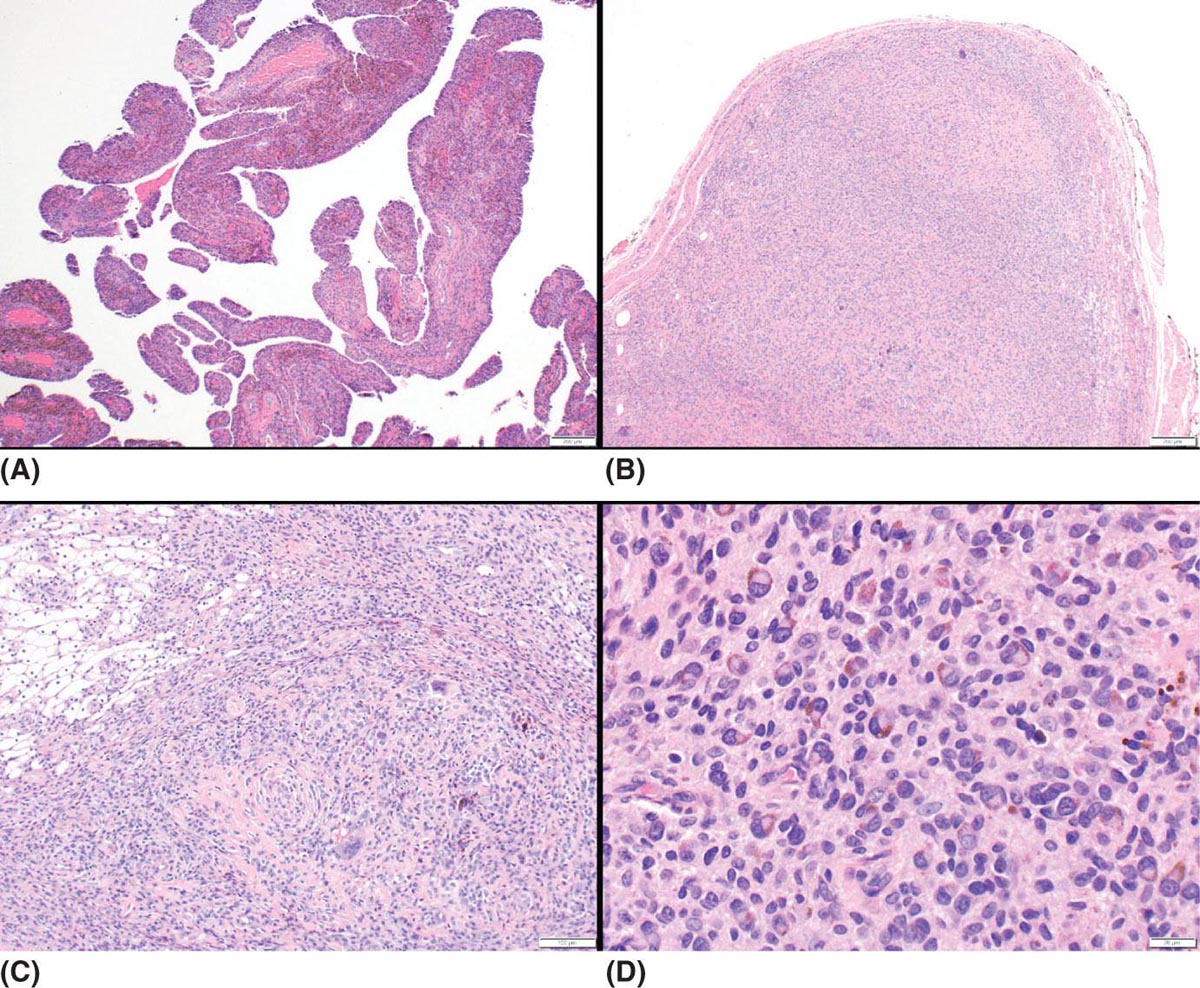

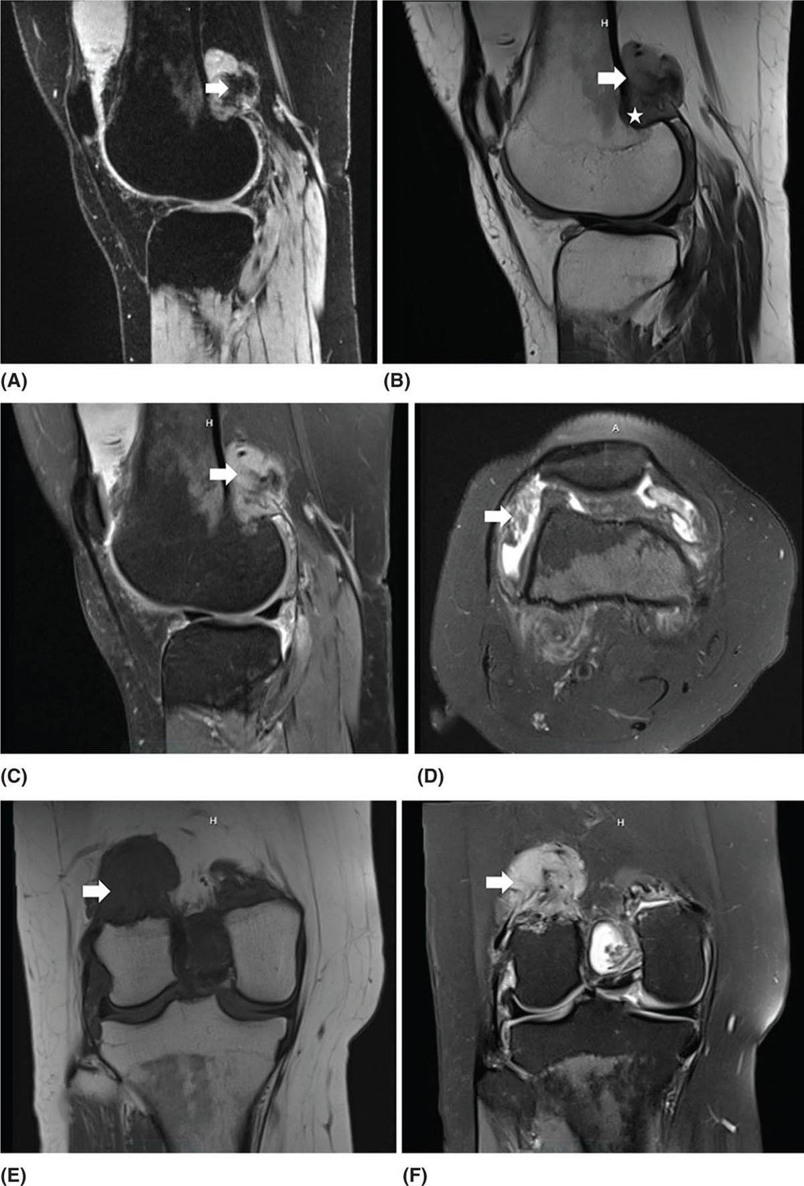

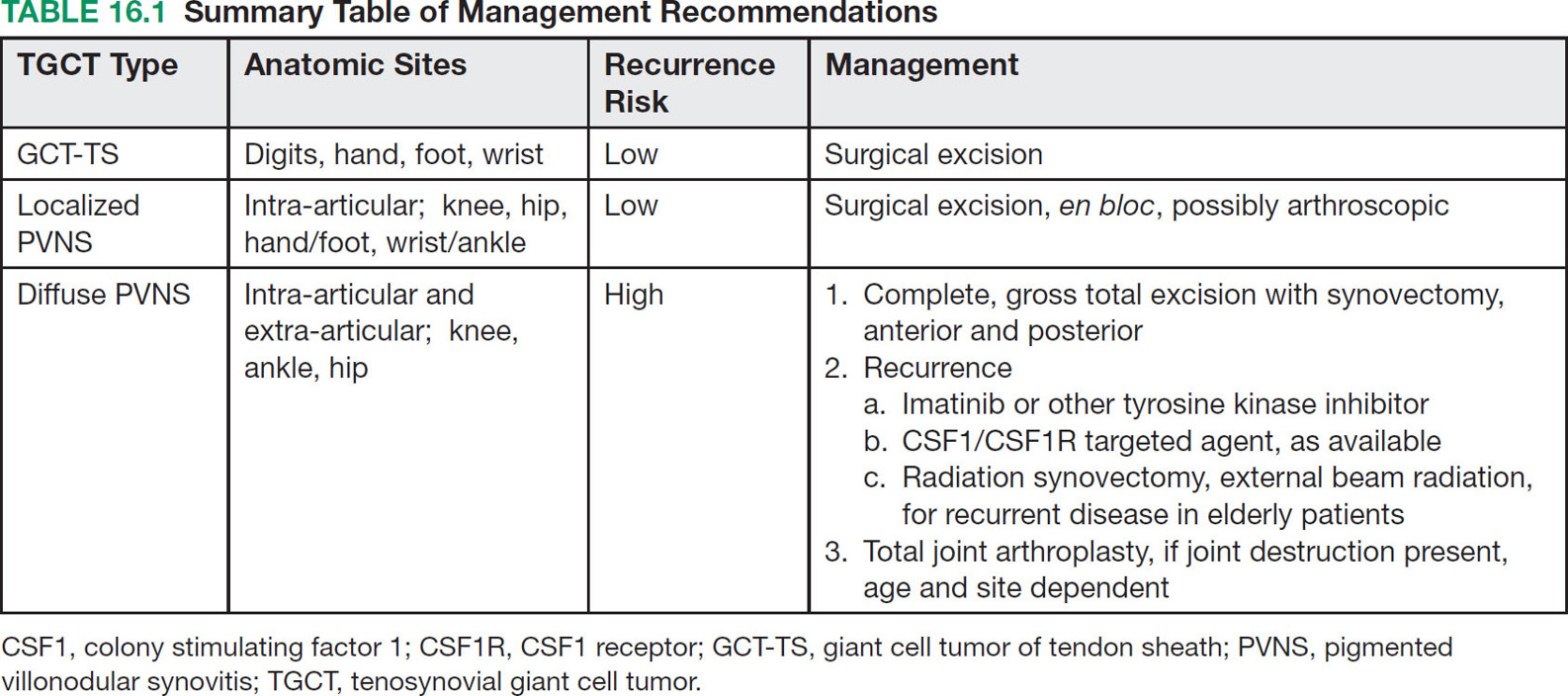

22116 Tenosynovial Giant Cell Tumor/Pigmented Villonodular Synovitis The term “pigmented villonodular synovitis” (PVNS) was coined in 1941 and is based upon the gross appearance of xanthomatous nodular densities arising in a synovial joint. Masses that arise from extra-articular synovial tissue of the tendon sheaths were also recognized, but it was unclear if these were neoplastic or reactive in etiology, and the terms giant cell tumor of tendon sheath (GCT-TS) and nodular tenosynovitis were used to describe these entities. More recently, the 2013 World Health Organization soft tissue classification schema categorized the origin of all of these entities as a “so-called fibrohistiocytic origin tumor,” termed tenosynovial giant cell tumor (TGCT) with the older traditional terms considered different forms of TGCT. The clinical spectrum of diseases caused by TGCT is broad, ranging from benign, small nodular growths in the tendon sheaths of the digits (giant cell tumor of tendon sheath, GCT-TS) to intra-articular soft tissue masses (PVNS), either focal or involving diffuse synovitis, with or without extra-articular extension, to a rarely found malignant tumor with fatal metastases. While surgical excision continues to be the initial treatment for both giant cell tumor of tendon sheath and localized PVNS, the management of diffuse PVNS is likely to evolve as other effective, nonsurgical therapies become available. This chapter reviews the diagnostic approach, recommended imaging, and general therapeutic approach for the different forms of TGCT. synovitis, nodule, giant cell tumor, tendon sheath, intra-articular, mass, diffuse colony stimulating factor-1, pigmented villonodular synovitis, surgical excision, surgical resection, tenosynovial giant cell tumor, treatment General Surgery, Giant Cell Tumor of Tendon Sheath, Macrophage Colony-Stimulating Factor, Synovitis, Pigmented Villonodular, Therapeutics INTRODUCTION A mass-like growth arising from the synovial tissue was described by several early authors,1–3 but it was not until 1941 that Jaffe and Lichenstein4 coined the term pigmented villonodular synovitis (PVNS), based upon the gross appearance of xanthomatous nodular densities arising in a synovial joint. This term continues to be used in modern parlance. Masses that arise from extra-articular synovial tissue of the tendon sheaths were also recognized, but it was unclear if these were neoplastic or reactive in etiology and the terms giant cell tumor of tendon sheath (GCT-TS) and nodular tenosynovitis were used to describe these entities. More recently, the 2013 World Health Organization soft tissue classification schema categorized the origin of all of these entities as a “so-called fibrohistiocytic origin tumor,” termed tenosynovial giant cell tumor (TGCT)5 with the older traditional terms considered different forms of TGCT (Figure 16.1). The clinical spectrum of diseases caused by TGCT is broad, ranging from benign, small nodular growths in the tendon sheaths of the digits (giant cell tumor of tendon sheath, GCT-TS) to intra-articular soft tissue masses (PVNS), either focal or involving diffuse synovitis, with or without extra-articular extension, to a rarely found, but nonetheless described, malignant tumor with fatal metastases. This tumor usually occurs in middle-aged adults.6,7 Nearly always, clinicians encounter the benign nodular growth form in the tenosynovial tissues of the hand/wrist/foot or the intra-articular mass form in a synovial joint, most often the knee. When a nodular or solitary focal mass only is identified, the disease is considered localized. When multiple focal masses or extensive synovitis is present in a synovial joint, the disease is considered diffuse. The disease is usually monoarticular, with occasional polyarticular involvement when locally spread to a nearby, adjacent joint occurs, for example in the carpal joints of the wrist or the tibiotalar and subtalar joints of the hindfoot and ankle. Differentiation between a localized versus diffuse form of disease can be problematic when a focal intra-articular mass has some degree of reactive synovitis or changes from hemarthrosis present, but not sufficient to make a diagnosis of neoplastic involvement of the synovium. Despite the plethora of names and clinical presentation, the histologic findings (Figure 16.2) are the same for each of these entities, with the exception of the malignant type.5 For many years, the management of this disease has been focused on the local control of the disease, which could be slowly destructive to local tissues resulting in debilitating arthritis, or relatively indolent with minor symptoms that cause minimal disability for patients. More recently, research findings have clearly identified the clonal, neoplastic growth of this disease and molecular insights into the genetic background of the tumor have opened the door to targeted therapies that are under investigation. ESTIMATED INCIDENCE PER YEAR, GENDER, AND RACE Incidence TGCT is an uncommon benign tumor and according to cancer agencies, it is rare by any definition (National Cancer Institute: incidence <15 per 100,000 population; European Union: incidence <50 per 100,000). The true incidence of TGCT is not known exactly; however, three prior studies have provided some insight. From 1960 to 1976, Myers et al. performed a pathology review survey of 12 Tennessee hospitals finding 166 new cases of TGCT. When broken down by type, the incidence of GCT-TS was 9.2 cases per million population and for PVNS (localized and diffuse) 1.8 cases per million population.8 222From 1990 to 1997, a study from Edinburgh of localized type PVNS revealed an incidence of 20 cases per million.7 From 2009 to 2013, Mastboom et al. completed a survey of Dutch hospitals and found 2,815 cases involving digits and 1,323 cases involving nondigits. The incidences found were GCT-TS, 34 per million person-years; PVNS localized extremity, 11 per million; and PVNS diffuse, 5 per million.6 When adjusted for worldwide population data, the estimated incidences were GCT-TS, 29 per million; PVNS localized extremity, 10 per million; and PVNS diffuse, 4 per million.6 FIGURE 16.1 Types of tenosynovial giant cell tumor and nomenclature commonly used. FIGURE 16.2 Diffuse-type tenosynovial giant cell tumor (pigmented villonodular synovitis): Hematoxylin and eosin-stained sections demonstrate a synovium-based hemosiderin pigment-laden neoplasm with papillovillous (A) and nodular architecture (B) (H&E ×100). Higher magnification reveals a diffuse proliferation of mononuclear cells in a background of multinucleate giant cells, histiocytes, and lymphocytes (C) (H&E ×200). The neoplastic mononuclear cells are large, epithelioid with eccentrically placed nuclei and a wreath-like deposition of hemosiderin (“ladybug” cells) (D) (H&E ×400). H&E, hematoxylin and eosin. 223Gender A slight predilection for females is present in all epidemiologic studies of TGCT. The Tennessee study found a female/male ratio of 1.25:1 (p < .01).8 The Dutch study had a similar sex distribution of female to male, 1.5:1.6 The Edinburgh study of localized PVNS had a female/male ratio of 1.6:1.7 Race No studies have found any racial differences among black versus white versus other populations. MOST COMMON PRESENTING SYMPTOMS The clinical presentation for TGCT varies depending upon the anatomic site and disease type. For hand and foot localized disease, presentation was painless swelling (93%) in the Edinburgh study.7 Among the patients in the Tennessee study, GCT-TS patients most often presented with a mass (99%), of which 76% were asymptomatic. Among the PVNS patients, joint swelling (75%), pain (79%), or other dysfunction (37%) were much more common than a mass (10%). Symptoms usually develop over a long period of time. When a synovial joint is involved, patients notice the intermittent joint effusions, probably related to hemarthroses, and also complain of mechanical symptoms of locking and catching. Trauma is unlikely to be etiologic, given the rarity of disease, yet minor trauma, even from daily activities, may herald the onset of symptoms, especially if hemarthroses develop. The initiation of prospective clinical trials for targeted therapy agents has resulted in the collection of patient-reported outcomes measures. In a Phase 1 trial of pexidartinib for diffuse (19) and localized (3) PVNS, the most common symptoms cited by patients were pain (82%), swelling (86%), stiffness (73%), reduced range of motion (64%), and joint instability (64%).9 DIAGNOSTIC APPROACH The workup and subsequent diagnosis of TGCT is based upon clinical suspicion, after ruling out other more common intra-articular pathology, by performing a history and physical examination, MRI, and eventual tissue biopsy confirmation. Biopsy in the most common clinical scenarios will differ, depending upon the type of disease suspected and the anatomic site. For example, for GCT-TS involving either the digits, wrist, or other extra-articular sites, the size of the lesion is usually small, for example, <5 cm, and simple excisional biopsy is not only diagnostic but also adequate treatment for the disease. For the uncommon larger extra-articular lesions, concerns about a possible sarcoma are prudent and therefore incisional biopsy, or a core-needle biopsy, is warranted to preserve surgical options for a wide excision, should that become necessary. For intra-articular masses or joint synovitis, an arthroscopic biopsy is satisfactory, provided a sufficient amount of tissue is sampled. If the diagnosis can be made upon frozen section, then proceeding with surgical excision, as appropriate, under the same anesthetic can be undertaken. However, if a frozen section is equivocal, then it is optimal to delay any definitive procedure until the diagnosis is confirmed. RADIOGRAPHIC FEATURES AND RECOMMENDED IMAGING While plain radiographs are appropriate to look for either destructive joint changes or calcifications, which might suggest alternate diagnoses, the optimal imaging of TGCT is MRI (Figure 16.3).10–12 A gradient echo sequence is most diagnostic with the key finding being the blooming artifact that occurs from the presence of metal (iron) in the hemosiderin-laden tissue often present13 (Figure 16.3A). Other types of proprietary and nonproprietary gradient echo type sequences, for example, a fast field echo sequence, are acceptable as well.14 Both clinicians and imaging review centers for clinical trials use MRI for assessing both treatment response and surveillance for relapse.12,15 Metrics for measuring treatment response are lacking, however, as the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST)16 and Choi criteria17 have not been validated for this disease. Given the intra-articular and synovitic nature of some of the tumors, volumetric assessment using multiple MRI slices is likely to be the most accurate as opposed to measuring joint effusion or other parameters. TGCT demonstrates hypermetabolic activity on PET, which is therefore a modality that is sensitive for detecting TGCT, either primary or recurrent; however, hypermetabolic regions must be differentiated from either metastatic or other primary sarcomas by either other techniques or clinical correlation as PET is not specific enough to make this distinction.18–20 FIGURE 16.3 MRI of the right knee of a 26-year-old woman with several months of gradually increasing and intermittent knee swelling followed by 3 months of persistent knee swelling, decreased range of motion, and discomfort. (A) Sagittal gradient echo sequence demonstrating a dark signal void (blooming) of pigmented villonodular synovitis (arrow). (B) Sagittal T2 sequence demonstrating low to intermediate signal characteristic of pigmented villonodular synovitis (arrow) and periarticular bone erosion just proximal to the femoral condyle (star). (C) Sagittal fat-saturated proton density sequence also demonstrating low to intermediate signal of pigmented villonodular synovitis (arrow) and additional pigmented villonodular synovitis signal behind the posterior horn of the meniscus. (D) Axial fat-saturated T2 sequence showing pigmented villonodular synovitis in the lateral gutter (arrow). (E) Coronal T1 sequence shows low signal (arrow). (F) Coronal fat-saturated proton density sequence with pigmented villonodular synovitis next to femoral condyle (arrow). 225MOLECULAR ABERRATION DRIVING THE TUMOR TGCT is a clonal neoplasm that is typically characterized by rearrangements, involving the short arm of chromosome 1 (1p11–13) besides chromosome 5 and 7 trisomies.21,22 The majority of the cases show rearrangements of the macrophage colony stimulating factor-1 (CSF1) gene located at the 1p13 locus.23 Although the most common translocation partner is COL6A3 at 2q37 [t(1;2)(p13;q37)],24,25 multiple other fusions, including a novel CSF1-S100A10 fusion gene and CSF1 transcript have also been documented.21,22,25,26 These aberrations can be detected by cytogenetic analyses, such as karyotyping and in situ hybridization as well as by reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) and RNA sequencing techniques. The neoplastic cells harboring the CSF1 fusion transcripts that induce overexpression of the protein constitute only a minority of the tumor mass, the bulk of which is made up of CSF1R (CSF1 receptor) containing reactive cells of the monocyte–macrophage lineage. This suggests the neoplastic cells create a tumor landscape that results in autocrine proliferation as well as the recruitment and induction of nonneoplastic macrophages and osteoclast-like giant cells.27 The overexpression of CSF1 and CSF1R is also seen in cases of TGCT that do not harbor translocations, suggesting alternative mechanisms of CSF1 upregulation.23,27 In addition to CSF1 overexpression, Huang et al.28 have shown alterations of cyclin A, P53, and 15q region in a cohort of malignant TCGT cases. The latter events may represent mechanisms leading to the rarely encountered malignant transformation in these tumors. From a management perspective, especially in cases that are recurrent or locally advanced, the abundance of CSF1R transmembrane tyrosine kinase receptors in these tumors offers a promising therapeutic target. The differential diagnosis of TCGT includes other neoplasms and reactive synovitides, such as hemosiderotic synovitis, detritic synovitis, rheumatoid arthritis, crystal associated arthropathies, and chronic nonspecific synovitis that may result in synovial proliferation, inflammation, and hemosiderin deposition. However, these disorders do not exhibit a diffuse proliferation of mononuclear epithelioid cells in the typical heterogeneous background of multinucleate giant cells, histiocytes, and lymphocytes as seen in TCGT (Figure 16.2). In addition, although CSF1 may be overexpressed in the lining cells of some of the reactive entities,27 the characteristic molecular findings found in TCGT are not present in other diseases. COMMON ANATOMIC LOCATIONS Excluding the digits, the knee is by far the most common anatomic site for both localized and diffuse PVNS (46% and 64%, respectively).6 Other common sites for localized disease are the hand/foot (30%) and the wrist and ankle (17%), while for the diffuse form, the ankle (10%) and hip (9%) are more common, and the hand and foot are less common (6%). GENERAL THERAPEUTIC APPROACH Giant Cell Tumor–Tendon Sheath As this usually occurs in the digits of the hand and foot or around the wrist and is localized, surgical excision is the mainstay of treatment (Table 16.1). Most clinical presentations involve a differential diagnosis of other types of tenosynovitis. Prior steroid injections may have been administered. Upon surgical exposure, either a xanthomatous type nodule or hypertrophic synovium is usually evident. Complete, gross total excision, en bloc as possible, results in successful local control of the disease in 85% to 90% of cases.29–32 Localized Pigmented Villonodular Synovitis The clinical presentation of this type of disease is usually an intra-articular focal mass associated with mechanical symptoms of joint dysfunction. In many cases, the MRI alone, with appropriate gradient echo sequences, is sufficient to have a high index of suspicion for the disease. Usually the differential diagnosis includes other intra-articular masses, such as synovial chondromatosis, lipoma arborescens, rheumatoid arthritis, gout, or amyloid associated arthropathy. Intra-articular masses are almost always benign, although cases of intra-articular sarcomas have been reported. More often, an extra-articular sarcoma has grown through and invaginated the synovial membrane, appearing as an intra-articular mass.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree