Fig. 30.1

T-cell activation and mechanism of action of ipilimumab. APC antigen-presenting cell, CTLA-4 cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen-4, TCR T-cell receptor, MHC major histocompatibility complex

Table 30.1

Evolution of mWHO to irResponse criteria

CR | PR | SD | PD | |

WHOcriteria | Alllesionsgone | SPD of index lesions decreases 50 % from baseline new lesions not allowed | SPD of index lesions neither CR, PR, nor new lesions not allowed | SPD of index lesions increases 25 % from nadir and/or unequivocal progression of non-index and/or new lesions |

irRC | irPR | irSD | irPD | |

irResponsecriteria | Alllesionsgone | SPD of index + any new lesions decreases 50 % from baseline new lesions allowed | SPD of index + any new lesions neither irRC, irPR, nor irPD new lesions allowed | SPD of index + any new lesions increases 25 % from nadir irPD is based on SPD only |

Based on preclinical data suggesting synergy between ipilimumab and vaccines in melanoma, a randomized double-blind phase III trial of ipilimumab 3 mg/kg with or without a peptide vaccine, gp100, was undertaken [44]. A total of 676 HLA-A-0201-restricted melanoma patients, with unresectable stage III or IV disease, were randomized. Ipilimumab induction therapy was administered every 3 weeks for four consecutive doses without maintenance, with responding patients eligible for re-induction at relapse. The median OS in the ipilimumab alone group was 10.1 months, as compared with 10.0 months in the ipilimumab plus gp100 group, and 6.4 months in the gp100 alone group (P = .003) (Fig. 30.2). A phase III trial of ipilimumab at the dose of 10 mg/kg with DTIC versus DTIC plus placebo in untreated patients with advanced melanoma completed accrual in 2008 and survival data were published on 2011 [45]. Overall survival was significantly better in the combination arm (11.2 vs 9.1 months) with higher survival rates at 1, 2, and 3 years. A relevant result was that after 2 years, there was a stable 10 % increase in the population of patients who appeared to have longer term response and the potential of cure from this therapy: estimated 2-year overall survival was 28.5 % with ipilimumab and DTIC, compared with 17.9 % with DTIC alone. The types of adverse events were consistent with those seen in prior studies of ipilimumab. On March 2011, ipilimumab became the first drug in more than a decade to be approved by FDA for the treatment of unresectable or metastatic melanoma. On July 2011 EMA approved Ipilimumab after first line treatment.

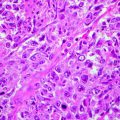

Fig. 30.2

Kaplan-Meier curve for overall survival

It is noteworthy to highlight that ipilimumab produces an uncommon, mechanism-related spectrum of autoimmune or immune-related adverse events (irAEs), creating unique challenges in diagnosis and clinical management. These irAEs are dose dependent and can occur quite rapidly. They include severe rash (50 % of cases); diarrhea and enterocolitis (10–35 % of cases); hypophysitis (5 % of cases); hepatitis (2–20 % of cases); and, more rarely, uveitis, pancreatitis, neuropathy, severe leucopenia, and red cell aplasia. Diarrhea and colitis, histologically resembling ulcerative colitis, often have a rapid onset and can, if untreated, lead to a fatal bowel perforation and septicemia. Mortality as high as 5 % has been reported. Safety guidelines recommend bowel rest and supportive care, as well as systemic steroids as first-line intervention with most patients responding to this treatment. Patients should be started on 1 mg/kg of methylprednisolone or prednisone twice daily, and the corticosteroids should be gradually tapered over 30 days or longer. When necessary, in patients with symptoms despite initiation of corticosteroids, relapse of symptoms after initial response, or partial response to corticosteroids, should be treated with the antitumor necrosis factor antibody infliximab at a dose of 5 mg/kg. Hepatitis with elevation of transaminase to over 500 U/L has also been reported. Liver function test results should be monitored before each dose of ipilimumab. Grade 3 or 4 hepatitis should be treated with steroids initially, followed sequentially by mycophenolate mofetil, tacrolimus, and, eventually, infliximab. Hypophysitis is the most commonly reported endocrine adverse reaction associated with ipilimumab. Symptoms of hormone deficiency include fatigue, insomnia, loss of libido, anorexia, weight loss, severe hyponatremia, hypothyroidism, and/or symptoms mimicking Addison disease. Unlike most other irAEs, endocrine dysfunction has a protracted course and is irreversible in many cases. It is noteworthy that patients experiencing an irAE have a higher chance of having an antitumor response to ipilimumab. In this context, the studies are in progress to identify host- or tumor-related factors that can be used as predictive biomarker. In a pooled analysis of studies CA184-007, CA184-008, and CA184-022 (and confirmed prospectively in study CA184-004), higher peripheral blood absolute lymphocyte counts (ALC) were significantly associated with clinical activity. Data have emerged recently showing that hair depigmentation develops alongside durable responses to ipilimumab in patients with advanced melanoma. Hair depigmentation suggests an association between induced autoimmunity and clinical benefit and could be a potential surrogate for response in some patients. Ipilimumab is the first-in class of a series of immunomodulating antibodies that are in clinical development such as antiPD1, antiPDL1, antiCD137. Some of these agent are being investigated in clinical trials.

Emerging Therapies for Patients with Metastatic Melanoma

Among the pathways deregulated in melanoma, the RAS/RAF/MEK/ERK pathway is an attractive target based on its role in promoting cell proliferation, invasion, and resistance to apoptosis. Beyond the presence of NRAS mutations in approximately 20 % of all melanomas, the basis for this constitutive activation was not well understood. In 2002, the BRAF mutation was discovered in a screen for mutations in the RAF genes. Subsequent biochemical investigations confirmed the role of mutated BRAF in constitutive ERK signaling and in stimulating proliferation and survival. BRAF mutations have been found in approximately 60 % patients, primarily in young individuals with melanoma originating on non-chronically sun-damaged skin [46, 47]. One of the earlier BRAF inhibitors investigated was the multikinase inhibitor sorafenib, which targets BRAF, CRAF, and the VEGF and PDGF receptor tyrosine kinases. As sorafenib was a relatively nonselective BRAF inhibitor, not significant clinical activity was demonstrated in patients with advanced melanoma [48]. However, when combined with chemotherapeutic agents, including carboplatin and paclitaxel, or temozolomide, it showed greater activity leading to phase III trials, which eventually failed both in first line and second line [49, 50]. The failure of sorafenib suggested the need for a more potent and targeted approach. The most common BRAF mutation (in approximately 90 % of clinical pathology samples) is the T1799A point mutation, in which a T → A transversion results in an amino acid substitution at position 600 in BRAF, from a valine (V) to a glutamic acid (E). This mutation occurs within the activation segment of the kinase domain, resulting in the protein taking on a constitutive active configuration [51]. Given the prevalence of this mutation in melanoma, there has been an intense interest in selective BRAF inhibitors. In a recent phase I trial, vemurafenib (PLX4032), an oral selective inhibitor of oncogenic BRAF V600E kinase, induced an objective clinical response in 81 % of patients with BRAF V600E mutation-positive melanoma [52]. The most frequent adverse events were arthralgia, rash, nausea, photosensitivity, fatigue, pruritus, and palmar-plantar dysesthesia. Interestingly, squamous cell carcinomas, keratoacanthoma subtype, developed in 31 % of the patients. The majority were resected and none led to discontinuation of treatment. A phase II trial (BRIM 2) involving patients who had received previous treatment for melanoma, positive for the BRAF V600E mutation, showed a best ORR greater than 52 %, with a median duration of response of nearly 7 months, and a median PFS greater than 6 months [53]. A phase III (BRIM 3) trial comparing the efficacy of PLX4032 with that of DTIC in 675 patients with previously untreated, metastatic melanoma positive for the BRAF V600E mutation was published recently [54]. In the interim analysis for OS (see Fig. 30.3) and final analysis for PFS, vemurafenib was associated with a relative reduction of 63 % in the risk of death and of 74 % in the risk of either death or disease progression, as compared with DTIC (P < .001 for both comparisons). Response rates were 48 % for vemurafenib and 5 % for DTIC. On August 2011, FDA approved Vemurafenib tablets (Zelboraf, made by Hoffmann –La Roche Inc.) for the treatment of patients with unresectable or metastatic melanoma with the BRAF V600E mutation as detected by an FDA approved test. On February 2012 EMA approved Vemurafenib in monotherapy for the treatment of adult patients with BRAF V600 mutation positive unresectable or metastatic melanoma. The second selective BRAF inhibitor to enter clinical development was GSK2118436. In a phase I/II clinical trial, patients with metastatic melanoma harboring BRAF mutations were accrued [55]. At the two highest doses evaluated, 150 and 250 mg twice daily, objective responses were observed in 10 of 16 patients with BRAF V600E. Of note, five patients with the BRAF V600K mutations were enrolled at the highest doses evaluated, and all had evidence of tumor regression. In addition to seeing responses at various sites of visceral metastatic disease, evidence of regression was observed early in the course of therapy in several patients with small previously untreated brain metastases [56]. The most common toxicities observed were mild-to-moderate fever, fatigue, headache, nausea, and vomiting. A first-line trial comparing GSK2118436 to DTIC in treatment naive metastatic melanoma patients documented that Dabrafenib significantly improved progression free survival compared with Dacarbazine [57].

Fig. 30.3

Overall survival. Kaplan-Meier estimates of survival in patients in the intention-to-treat population

Although dramatic clinical activity has been shown with single-agent BRAF-targeted therapy, the antitumor effect is of limited duration.

Resistance to BRAF-inhibitor therapy is common and rapidly acquired in the majority of patients [58, 59]. No Mek inhibitor has demonstrated significant clinical activity in BRAF – mutated melanoma in the phase II setting; Selumetinib had a RR of only 10 % in BRAF- mutant melanoma [60] and PD 0325901 was poorly tolerated [61, 62]. In the first published phase III trial Trametinib (GSK 1120212), as compare with chemotherapy improved rates of progression free and overall survival among patients who had metastatic melanoma with a BRAF V600E e V600K mutation [63]. The combination of Dabrafenib and Trametinib increase the rate of pirexia insteed PFS significantly improve [64]. Phase III combination of BRAF and Mek inhibitors studies are currently being tested.

KIT is a receptor tyrosine kinase that plays an important role in proliferation, development, and survival of melanocytes, hematopoietic cells, and germ cells and is ubiquitously expressed in mature melanocytes. Activating mutations and gene amplification of KIT have been found in 39 % of mucosal, 36 % of acral, and 28 % of melanomas that arise in chronically sun-damaged skin [65]. Recent reports, although limited in number, describe dramatic and durable responses to treatment with imatinib mesylate and other KIT inhibitors. Several multicenter phase II trials are currently under way to evaluate KIT-targeted agents, including imatinib, sunitinib, nilotinib, and dasatinib, in melanoma patients whose tumors harbor KIT aberrations. A randomized phase III trial will evaluate nilotinib, a multitarget kinase inhibitor, compared with DTIC as first-line therapy in patients with advanced melanoma harboring KIT mutations. Finally, as with BRAF-targeted therapies, understanding the potential mechanisms of resistance to KIT-targeted therapy is an active area of investigation.

Glossary

Adjuvant therapy

is a treatment that is given in addition to the primary, main or initial treatment.

BRAF

is a human gene that makes a protein called B-Raf. The gene is also referred to as proto-oncogene B-Raf and v-Raf murine sarcoma viral oncogene homolog B1, while the protein is more formally known as serine/threonine-protein kinase B-Raf.

Interferon-alpha

is a pleiotropic cytokine belonging to type I IFN, currently used in cancer patients.

References

1.

2.

Corona R, Mele A, Amini M, et al. Interobserver variability on the histopathologic diagnosis of cutaneous melanoma and other pigmented skin lesions. J Clin Oncol. 1996;14(4):1218–23.PubMed

3.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree