Despite important therapeutic innovations within the past several years, the odds of patients with metastatic breast cancer achieving complete response remain extremely low. Judiciously applied multiple endocrine, chemotherapeutic, or biologic therapies attempt to induce a series of remissions and ultimately adequate palliation. Patients with localized breast or chest wall recurrences, however, may be long-term survivors with appropriate therapy. At present, there is a lack of both a consensus management algorithm and an ideal treatment model of specific subsets of women. Before treatment selection for recurrent or metastatic cancer, restaging to evaluate extent of disease is indicated. In the absence of symptomatic disease, the usefulness of a routine diagnostic work-up is not evidence-based. Diagnostic tests and staging procedures are directed by the organ sites most frequently involved in metastatic breast cancer and by patient signs and symptoms. Documentation of initial metastatic sites is helpful in treatment planning and in later assessment of response to treatment. Over the past 45 years, the American Joint Committee on Cancer has regularly updated its staging standards to incorporate advances in prognostic technology.1,2 However, until the development of prognostic indices based on molecular markers are incorporated, Tumor-Node-Metastasis (TNM) staging continues to quantify only the physical extent of the disease. Anatomic staging continues to play a major role in guiding treatment decisions. Clinical decision-making still involves a number of patient and tumor characteristics.3-5 Pretreatment prognostic (measures of tumor burden or hormonal receptor status) and predictive factors (hormonal receptor and HER-2/neu status) are considered in order to select a therapy most likely to benefit patients.6

Given the biologic heterogeneity of the disease in primary and metastatic settings, the potential for continued mutation, and the variety of treatment options available, the information obtained at the initial diagnosis of breast cancer may not be as relevant to planning the treatment for recurrence in women who have recurrent metastatic breast cancer years after their initial diagnosis. Appropriate risk and biologic stratification in breast cancer will offer the unique opportunity for development of more effectively tailored targeted therapies.

Obtaining a comprehensive history is essential to provide pertinent information of primary diagnosis, treatment management, toxicity complications, and interval period to disease recurrence. Comorbidity, current medications, allergies, and menopause status is important for management planning and treatment selection. There is a great heterogeneity in the clinical presentation of metastatic breast cancer. Certain characteristics can be used to predict favorable clinical course, including long disease-free interval, hormone receptor positivity, response to prior endocrine therapy or chemotherapy, single site of metastases, and lack of liver, parenchymal lung, or central nervous system involvement. Early failure (< 6 months) on hormone therapy suggests that cytotoxic chemotherapy should be the next modality employed.

In metastatic breast cancer, maintenance of quality of life and elimination of cancer-related symptoms is the major objective. Patients with estrogen receptor–positive tumors are especially unlikely to suffer recurrence initially in the brain or liver. Routine brain and liver imaging procedures are expensive and are not indicated in the absence of symptoms, physical findings, or laboratory values suggesting involvement.

Physical examination should focus on the detection of metastases on the chest wall, skin, remaining breast, regional and distant lymph nodes, axial skeleton, lungs, liver, and central nervous system. One-third of patients with recurrent breast cancer present initially with local recurrence involving regional lymph nodes or the chest wall, with the diagnosis of recurrence made on clinical examination with subsequent biopsy confirmation. Local chest wall recurrence after mastectomy is usually the harbinger of widespread disease. In a subset of patients, it may be the only site of recurrence and surgery and/or radiation therapy may be curative. Patients with chest wall recurrences of less than 3 cm, axillary and internal mammary node recurrence (not supraclavicular, which has a poorer survival), and a greater than 2-year disease-free interval before recurrence have the best chance for prolonged survival.7-10

A complete diagnostic imaging evaluation is a major component of the staging workup of breast cancer patients. Imaging determines the extent of disease (tumor size, multifocality, multicentricity) in the breast(s), excludes or identifies additional areas of malignancy in the contralateral breast, and excludes or identifies nodal involvement and/or distant metastases.

The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) provides guidelines for the imaging staging workup of breast cancer patients.11 In general practice, a diagnostic bilateral mammogram is required for the workup of stages 0 to IV. By excluding axillary nodal metastases, ultrasound and ultrasound-guided biopsy of indeterminate lymph nodes will support the diagnosis of stage I disease and will evaluate the extent of regional nodal involvement in stages II to IV. Ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) will exclude stage IIB and IIIA disease and confirm stage IIIB disease with the exclusion or identification of skin and chest wall involvement.

Bone scans, chest x-rays, and abdominal ultrasound, computed tomography (CT), or MRI are generally recommended only in the presence of symptoms for patients with stage I, II, and IIIA breast cancer and for patients who present with stage IIIB or IIIC disease with or without the presence of symptoms. The diagnosis of stage IV disease will be supported by plain films of the chest and axial skeleton; bone scans; chest CT or MRI; abdominal ultrasound, CT, or MRI; and/or pelvis ultrasound, CT, or MRI and biopsy confirmation that suspicious findings represent distant metastases. In spite of these formal recommendations from the NCCN, many surgeons and oncologists consider and perform systemic imaging, often positron emission tomography (PET)/CT, abdominal and chest CT, for patients with node-positive, stage II or greater extent of disease. The necessity of these tests is a subject of debate, and current guidelines should be discussed within the multidisciplinary group in which the patient is treated. Additionally, many systemic therapy clinical trials may have specific criteria for staging patients before initiation of therapy.

Mammography is the backbone imaging modality of breast cancer staging and is most commonly the first test that is interpreted. With consultations, the radiologist must review all prior imaging studies from outside institution(s) and determine whether the submitted images are adequate to make an appropriate diagnosis. If inadequate, the images must be repeated. The radiologist must also determine whether additional imaging studies are needed. In the case of a suspected incomplete or unsuccessful excision, residual calcifications and mass lesions will be noted on mammography. Ultrasound and MRI are helpful in the evaluation of residual mammographically occult uncalcified tumor.

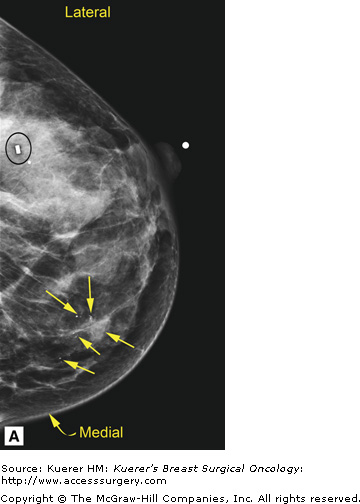

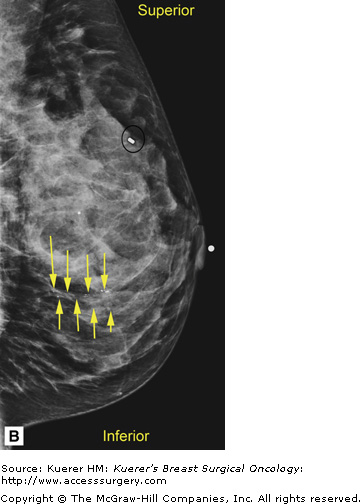

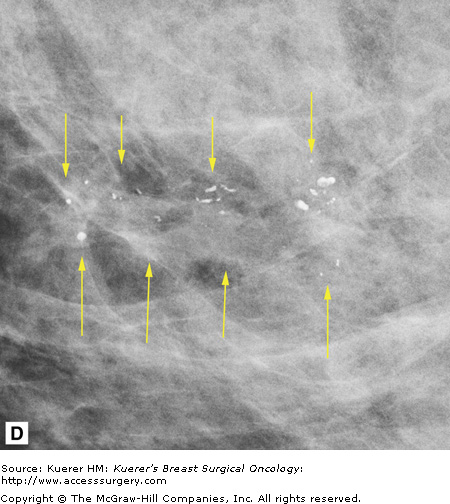

In general, mammography (or any imaging study) cannot completely exclude cancer, but mammography is consistently able to detect unsuspected breast cancer, even in women whose clinically suspicious finding is proven benign.12 All findings must be adequately imaged and thoroughly documented in the radiology report. The 9 o’clock position or location and the distance from the nipple of the suspicious finding(s) are recorded. If multiple suspicious findings are noted, then percutaneous biopsies are performed to determine multifocality or multicentricity. Any secondary signs of malignancy are recorded. With suspicious calcifications, the full extent of the calcifications is assessed, which includes measuring the volume of calcifications and the distance from the calcifications to the closest overlying skin margin and to the nipple (Fig. 36-1). A large volume of calcifications may prohibit breast conservation. Completely documented mammogram findings can then be correlated with findings seen on additional imaging studies.

Figure 36-1

(A) Cranial-caudal (CC) view and (B) lateral-medial (LM) view show calcifications (arrows) in the 9 o’clock position of the left breast located 5 cm from the nipple. The approximate volume of calcifications is 1.8 cm (LM measurement) × 1.7 cm (anterior-posterior measurement) × 1 cm (superior-inferior measurement). The medial skin margin is closest (curved arrow). The circle annotates a marker clip that denotes a prior benign biopsy. (C) CC magnification view and (D) LM magnification view characterize the calcifications (arrows) as heterogeneous, warranting biopsy.

Ultrasound is used in the evaluation of mammographically occult uncalcified tumor, mammographically identifiable tumor, the evaluation of palpable masses, and to thoroughly evaluate the regional nodal basins. A good routine breast ultrasound study includes evaluation of the whole breast and the infraclavicular, axillary, and internal mammary nodal regions. If indeterminate or suspicious infraclavicular lymph nodes are identified, the supraclavicular nodal region should be scanned. All sonographic findings are correlated with all mammographic findings and other findings seen on additional imaging studies. Suspicious masses and the highest level lymph nodes are biopsied.

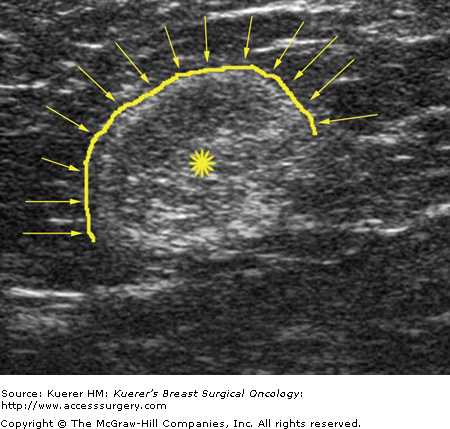

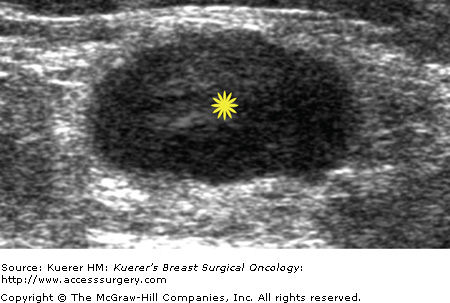

Metastatic involvement of regional nodes is an important prognostic parameter. The presence or absence of axillary metastases is the strongest prognostic indicator available for breast cancer.13-15 Although no imaging method can detect or exclude microscopic metastases, a positive diagnosis obtained with cytologic or histologic confirmation is quite reliable and can be used to influence treatment decisions. Some sonographic features that favor benignity include lymph nodes that are predominantly hyperechoic, the presence of a thin homogeneous symmetrical cortical rim around the hyperechoic hilar fat (Fig. 36-2), and symmetric cortical lobulations similar to contralateral axillary lymph nodes.16 Suspicious or metastatic-appearing sonographic features would include thickening or eccentric lobulation of the hypoechoic cortical rim, compression or displacement of the fatty hyperechoic hilum, and/or complete replacement of the hilar fat by hypoechoic tissue (Fig. 36-3).16

Fine-needle aspiration of indeterminate, suspicious, or metastatic-appearing lymph nodes (Fig. 36-4) can provide a more definitive diagnosis than ultrasound alone. Krishnamurthy et al4 found that the overall sensitivity of ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration was 86.4%, the specificity was 100%, the diagnostic accuracy was 79%, the positive predictive value was 100%, and the negative predictive value was 67%. Bedrosian et al17 reported a sensitivity of 25% and specificity of 100%. Overall, suspicious or indeterminate lymph nodes were more likely to contain metastases at final pathology than benign-appearing lymph nodes.17 Core biopsy of indeterminate, suspicious, or metastatic-appearing lymph nodes may also be done, particularly when dedicated cytopathology is unavailable. In the case of core biopsy of axillary lymph nodes, the imager must be careful to avoid the axillary vasculature.

Berg et al18 found that in women with increased risk for breast cancer, adding a screening ultrasound examination to routine mammography revealed 28% more cancers than with mammography alone. However, the additional ultrasound examination substantially increased the rates of false-positive findings and unnecessary biopsies.18