(1)

State University of New York at Buffalo Kaleida Health, Buffalo, NY, USA

The therapeutic intervention of a surgical oncologist in dealing with solid tumors is usually performed through procedures aimed at complete extirpation of the tumor and preservation of functional anatomy as much as it is feasible.

Integration of Modalities

It is imperative, however, that the surgical oncologist be familiar with the applications and relative effectiveness of the other modalities of treatment, such as chemotherapy, radiation, and possibly immunotherapy. In some cases, such as rhabdomyosarcoma and osteogenic or Ewing sarcoma of the bone, neoadjuvant therapy is indicated initially in order to first shrink the tumor, thereby making the operation easier and improving survival. This therapy also allows assessment of the degree of necrosis of the tumor and of the effectiveness of the chemotherapy used, aiding the decision about continuing with the same protocol postoperatively. Although the main function of the surgical oncologist is to evaluate the resectability of a solid tumor and the possible benefit to the patient of resection, it is also appropriate to consider, based on the known literature, whether it may be best to abstain from operating on a patient who would not be likely to benefit because of the nature or stage of the tumor. Another alternative may be to delay the operation until other treatment modalities have had a chance to produce an effect. Nevertheless, the chief therapeutic modality of the surgical oncologist is the performance of a surgical procedure.

Goals for the surgical technique should be safety, oncological soundness (providing for a satisfactory margin and yet preserving functionally important structures), and a minimum of complications. A preoperative determination is made as to whether the surgical procedure could be potentially curative, or whether it would only be palliative. This distinction is often simple and obvious. Operating on a patient with limited expectations of improving his or her condition increases the surgeon’s responsibility to perform the procedure with a minimum of complications and a brief hospital stay. One should weigh the possible benefit of the contemplated operation for the patient versus the possible risk.

Tumor Biopsy

Before a surgical procedure is performed, one should have clear knowledge of the history of the tumor and the stage of the disease. To determine the histology of the tumor, a preoperative biopsy is needed. Fine needle aspiration (FNA) may provide information as to whether the cells are malignant, but it may be difficult for the pathologist to make a definitive diagnosis when the structure of the tissue is lacking. Diagnosis is made easier by knowing the organ from which the FNA was taken. Therefore, FNA is usually employed only in specific circumstances, such as a cold thyroid nodule or a mass in the head of the pancreas. More often, a core biopsy is preferred, in which a small stab-wound incision is made with a #11 blade under local anesthesia over the most protuberant part of the tumor (provided it is not close to major vessels or nerves), allowing the passage of a tru-cut needle several times into the tumor mass and the removal of tumor tissue for pathologic evaluation. Obviously, it is preferable to make several passes in different directions and to remove several cylindrical pieces of tissue in order to have sufficient diagnostic tissue for the pathologist to evaluate. The stab-wound incision may have to be away from the center of the tumor mass so that the needle avoids major blood vessels. For tumors located in areas relatively inaccessible to inspection and palpation, a guided percutaneous biopsy by an interventional radiologist may be preferable. In every biopsy, consideration should be given to the feasibility of including the biopsy tract in the definitive operation.

Another method of biopsy is the open biopsy, which usually can be done under local anesthesia with or without intravenous sedation. The incision for the open biopsy should be in conformity with the expected orientation of the definitive incision for tumor removal. In the extremities, the biopsy incision usually is a vertical, longitudinal incision along the long axis of the extremity; this type of incision provides versatility in its length for the exposure and resection of the tumor mass when the definitive incision is made.

It is preferable, however, for the biopsy incision to be at or close to the most protuberant part of the tumor, easily circumscribed with an elliptical incision in the definitive operation so that the flaps created for the two sides will share equally the degree of their development around the tumor, thus minimizing the incidence of flap necrosis.

The technique of open biopsy involves an incision that goes vertically through the subcutaneous fat to the fascia and then into the tumor mass. It is important to obtain an adequate portion of the tumor mass in order to have diagnostic tissue. Before the biopsy, the surgeon should study the available CT scans or MRIs that show the tumor, its extent, and its location and distance from the skin surface, in order to become aware of the necessary depth of the biopsy and to determine the length of the biopsy incision. For most sarcomas lying deep below the fascia, the fascia is opened and then one proceeds to cut down to the surface of the tumor and obtain a generous specimen. One should be careful not to take specimens only from very close to the surface of the tumor mass, as this may be simply reactive tissue from the periphery of the tumor mass, which is not diagnostic. Therefore, if there is any question as to the diagnostic adequacy of the removed tissue, a deeper biopsy should be attempted, provided that there is no evidence of any major vessels or nerves nearby. It is a good idea to submit the specimen to frozen section to make sure the pathologist has sufficient tissue for diagnosis. Ample tissue samples should be provided to the pathologist so that both frozen section and the appropriate permanent studies may be made. The advantage of having the pathologist do frozen section is that he or she may alert the surgeon about not having diagnostic tissue if the biopsy was not obtained from areas deep into the tumor, or conversely, that it contained only necrotic tissue in which the characteristic features of the tissue of origin are occasionally lost. The tissue obtained in the biopsy therefore should be taken from both peripheral and deeper areas of tumor.

Good hemostasis is important at the biopsy site, achieved by cauterizing the smaller bleeders, ligating or suture-ligating the larger vessels, and finally using figure-of-eight sutures to control vessels retracted within the wall of the biopsy cavity or the subcutaneous fat. Surgicel or other hemostatic material may be used, followed by closure in layers of the periphery of the tumor and the subcutaneous fat, starting from the deep layers of subcutaneous fat adjacent to the fascia and then the more superficial layers. Finally, a few interrupted, absorbable sutures can be placed in the deep dermis of each edge and tied to take away the tension from the closure of the skin itself, which can be done with a running, subcuticular suture of 4.0 or 3.0 monofilament absorbable suture or continuous over-and-over skin suture of monofilament nylon.

The reason for extra care with hemostasis and the closure in layers of the wound is to avoid extravasation and infiltration into the surrounding tissues of blood from the biopsy site, which may carry tumor cells with it and therefore cause local dissemination of the tumor. The other reason for the layer closure of the biopsy track is to prevent seepage of fluid carrying tumor cells to the skin surface of the incision. This risk is more likely to materialize when the definitive operation immediately follows the frozen section report. The use of a drain to drain the biopsy cavity is best avoided; if it must be used (as in the rare case of a deep axillary sentinel node biopsy, which requires extensive dissection), the drain track and its exit point should be placed adjacent to and in line with the biopsy incision, so that the drain and biopsy incision can be easily encompassed by the definitive incision, if the sentinel node turns out to be positive.

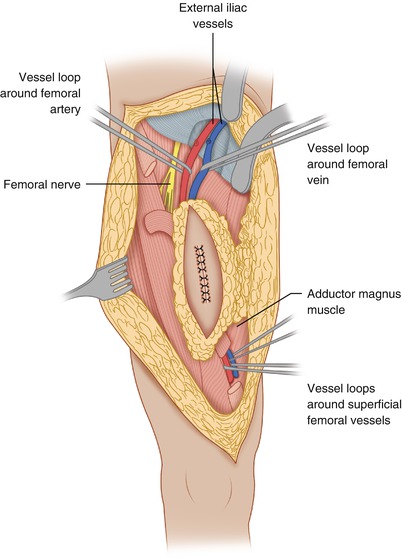

Resection of Extremity Sarcoma

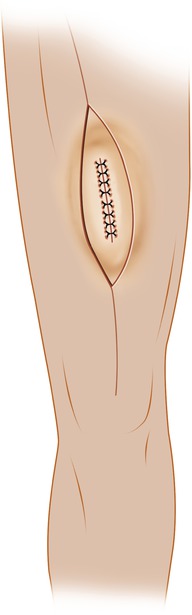

Figure 1.1 shows the elliptical incision carried out around the biopsy incision of a soft tissue sarcoma of the anterior thigh, extending far enough proximally and distally to allow identification of the approximate location of the end of the tumor mass. Around the elliptical portion of the biopsy incision, one develops flaps 3–4 mm thick for a lateral distance of 1–2 in.—in other words, sufficient to get away from the biopsy plane—and then one proceeds with dissection on top of the fascia, which is incised after the palpable extent of the tumor is passed (Fig. 1.2), provided that the preoperative CT scan or MRI and the operative findings indicate that the tumor is deep to the fascia. When the tumor is partly subcutaneous, the elliptical incision around the biopsy should include a larger section of skin, so that the incision is made well away from the tumor. In this case, a skin graft or flap rotation may be required at the end of the procedure. The portion of the incision proximal and distal to the elliptical incision is continued with a vertical dissection through the subcutaneous fat, using a scalpel and/or cautery all the way down to the fascia, given that one is already away from the area of the biopsy track and the tumor is known to be deep to the fascia. In other words, one does not have to make a flap thin all the way along the length of the flap; it is wiser to make the flap thin only in the area close to the tumor mass and/or the biopsy incision, and to make the flap thicker as one gets away from the area of the tumor. This policy considerably decreases the chance of flap necrosis and also diminishes the chances of excessive postoperative lymphorrhea and the incidence of lymphedema.

Fig. 1.1

Elliptical incision around the previous biopsy incision. It is extended proximally and distally for better exposure and control over the desired margin of resection

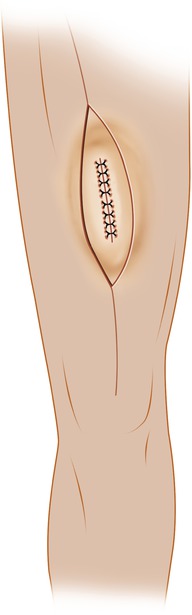

Fig. 1.2

Flaps have been developed medially and laterally around the biopsy incision

As soon as one feels that the flap development is slightly beyond the lateral extent of the tumor, the fascia is incised all the way around and longitudinally proximal and distal to the tumor to the corners of the incision, so that the anatomical structures (i.e., the underlying muscles beneath the fascia) are identified. Based on the preoperative x-ray studies and actual findings at the time of the operation, one should be able to tell which muscles need to be resected and begin to divide these muscles proximal and distal to the tumor. Figure 1.3 shows the division of the sartorius muscle, both proximally and distally. Dividing the involved muscles proximal and distal to the area of the tumor allows entry into a deeper plane, which, in combination with palpation of the exposed surface of the tumor mass, allows the determination of whether one needs to further develop the flap laterally. Absent this approach, the usual tendency is for unnecessarily wide flaps.