Melanoma accounts for less than 2% of skin cancer cases but causes most skin cancer–related deaths. Surgery continues to be the cornerstone of treatment of melanoma and surgical principles are guided by data derived from clinical research. This article examines the evolution of surgical techniques for the diagnosis and treatment of primary and locally recurrent melanoma.

Key points

- •

Early diagnosis of melanoma improves prognosis.

- •

Optimal margin width depends on the stage of the primary.

- •

Surgical excision is the preferred treatment of recurrent melanoma.

Introduction

Melanoma accounts for less than 2% of skin cancer cases, but is responsible for most skin cancer–related deaths. It is estimated that there will be 76,100 new diagnoses of melanoma and 9710 deaths in the United States in 2014.

Surgery continues to be the mainstay of care in the management of melanoma, whether it is for diagnostic, therapeutic, or palliative purposes. Forty years ago, most melanomas were excised widely with 3- to 5-cm margins, and many centers treated regional lymph nodes with routine elective lymph node dissection. This was based on the observation of local and locoregional recurrence in cases where the melanoma was narrowly excised, and it was found that surgical treatment of recurrence was difficult to impossible.

In some centers, wide excision of the primary melanoma was performed in continuity with excision of a broad strip of skin, subcutaneous tissue, and the nearest anatomic group of lymph nodes. This was based on Hogarth Pringle’s advice from three cases that he published in 1908. Over the past 40 years, there has been dramatic change in the surgical management of melanoma, which has been guided by astute clinical observations and rigorous clinical trials. More conservative margins are now considered adequate and routine complete lymph node dissections have been abandoned since the adoption of sentinel node (SN) biopsy. SN biopsy improves assessment of prognosis and in about 80% to 85% cases it also obviates complete lymph node dissections.

The goal of surgical treatment continues to be eradication of the primary lesion to achieve negative margins and assessment and treatment of regional spread to minimize the chances of local and locoregional relapse. This article details the rationale for margins of excision and discusses the surgical management of locally recurrent melanoma.

Introduction

Melanoma accounts for less than 2% of skin cancer cases, but is responsible for most skin cancer–related deaths. It is estimated that there will be 76,100 new diagnoses of melanoma and 9710 deaths in the United States in 2014.

Surgery continues to be the mainstay of care in the management of melanoma, whether it is for diagnostic, therapeutic, or palliative purposes. Forty years ago, most melanomas were excised widely with 3- to 5-cm margins, and many centers treated regional lymph nodes with routine elective lymph node dissection. This was based on the observation of local and locoregional recurrence in cases where the melanoma was narrowly excised, and it was found that surgical treatment of recurrence was difficult to impossible.

In some centers, wide excision of the primary melanoma was performed in continuity with excision of a broad strip of skin, subcutaneous tissue, and the nearest anatomic group of lymph nodes. This was based on Hogarth Pringle’s advice from three cases that he published in 1908. Over the past 40 years, there has been dramatic change in the surgical management of melanoma, which has been guided by astute clinical observations and rigorous clinical trials. More conservative margins are now considered adequate and routine complete lymph node dissections have been abandoned since the adoption of sentinel node (SN) biopsy. SN biopsy improves assessment of prognosis and in about 80% to 85% cases it also obviates complete lymph node dissections.

The goal of surgical treatment continues to be eradication of the primary lesion to achieve negative margins and assessment and treatment of regional spread to minimize the chances of local and locoregional relapse. This article details the rationale for margins of excision and discusses the surgical management of locally recurrent melanoma.

Diagnostic biopsy techniques

Diagnostic biopsy of a pigmented lesion can be performed in multiple ways ( Table 1 ). Excisional biopsy is the preferred method of evaluation of a pigmented lesion. Preliminary excision with 1- to 3-mm margins is considered desirable for appropriate diagnosis and treatment planning. Not only does it give direction regarding final excision margins, but measurement of depth, presence of ulceration, or high mitotic rate can also give direction regarding possibility of metastases to lymph nodes. This may warrant lymphatic mapping and SN biopsy.

| Type of Biopsy | Description | Utility |

|---|---|---|

| Excisional biopsy | Remove the lesion with 1- to 3-mm margins. Can be performed as an elliptical biopsy, a punch, or saucerization. | Preferred method of biopsy for pigmented lesions. |

| Incisional biopsy | A full-thickness biopsy of the thickest portion of the lesion. | Useful in certain anatomic areas, such as the face, ear, palm, sole, or digit; and in very large lesions. |

| Punch biopsy | A full-thickness biopsy that could be excisional if the lesion is very small. | Like incisional biopsy, it is useful if the lesion is large, or if the location is on the face or hand. |

| Shave biopsy | Involves removal of the superficial layers of the skin with a sharp blade. | Not the preferred method of biopsy. Performed in areas where the index of suspicion is low. Risk of incomplete depth analysis. |

However, in practice, other techniques of biopsy, such as incisional biopsy, shave biopsy, or punch biopsy, are commonly used. Biopsy technique has been debated because of the accuracy of these alternative methods of biopsy. The point of debate focuses not only on the completeness of diagnosis from these biopsies, but also the possibility that disruption of tumor may portend worse oncologic outcomes.

One of the earlier studies looked at 193 patients recorded in the California Tumor Registry treated between 1950 and 1954. Initial biopsies were performed in 115 patients and 55 were radically excised. The 10-year overall survival was 65.4% in the biopsy group versus 55.8% for those with initial complete excision. However, the study was limited in that only diameter of the lesion was recorded. Tumor thickness as a prognostic variable was not yet understood, and therefore not recorded.

Rampen and colleagues looked at incisional biopsies and reported that the risk of local tumor recurrence and metastatic potential may be increased by incisional procedures, by pushing tumor cells to the deep dermis or subcutaneous structures. In this small series of 76 patients, 14 patients who had incisional biopsies had reduced survival compared with 62 patients who had excisional biopsies. However, the authors did not stratify for other predictive factors. Austin and colleagues reported 48 cases of incisional biopsy for head and neck melanoma and reported a significant reduction of survival when compared with the excisional biopsy group. The median follow-up for this study was 36 months, and the only significant difference in either group was that patients in the incisional biopsy group were significantly older. They did not find any difference in local or regional recurrence. In contrast, a study by Griffiths and Briggs retrospectively analyzed 281 patients with clinical stage I invasive cutaneous melanoma from a period of 1967 to 1972 at the Frenchay Hospital in Bristol. They did not find any significant difference in outcome between patients who had received an incisional biopsy, minimal margin excisional biopsy, or primary wide excisional surgery.

Twenty years later, a study by Martin and colleagues looked at a subgroup of 215 patients with head and neck melanomas, and failed to show any significant differences in positive nodes, disease-free, distant disease-free, or overall survival among the excisional, incisional, or shave biopsy groups. Lederman and Sober looked prospectively at 472 patients with clinical stage I cutaneous melanoma, 353 had undergone total excisional biopsies and 119 had punch biopsies or partial excisions. All patients were grouped by four tumor thickness categories. Within these categories there was no significant difference between the incisional and the excisional biopsy groups. The authors recommended incisional biopsies for large lesions or for lesions located in cosmetically sensitive areas. Lees and Briggs performed a large retrospective study in 1991 that included 1086 patients. Of these 990 received a complete excision and 96 had an incisional biopsy. They stratified patients for age, gender, and tumor thickness and found no difference in mortality rates during a 5-year period.

Bong and colleagues evaluated 265 patients who had incisional biopsies, and matched to 469 cases of excisional biopsies from the database of the Scottish Melanoma Group. They found no difference in recurrence or disease-free survival. Molenkamp and colleagues looked at 471 patients who were stage I/II melanoma and underwent re-excision and a SN biopsy. They found that age, Breslow thickness, lymphatic invasion, and SN status were the most consistent and independent confounders of disease-free survival and overall survival. The site of primary melanoma and ulceration were also important confounders of survival. However, both the diagnostic biopsy type and presence of residual tumor cells in the re-excision specimen did not have a negative influence on disease-free and overall survival. With the rising incidence of melanoma, it is important for clinicians to be able to obtain a biopsy diagnosis, although incisional biopsy is not recommended; the presence of positive margins on excisional biopsy need not be considered a failure.

The underlying theme in all of the previously mentioned studies was that although an incisional biopsy or punch biopsy has not been shown to cause a worse disease-free and overall survival, it certainly carries the potential for a considerable sampling error and inaccurate histopathologic diagnosis leading to inaccurate staging. Also, although a shave biopsy has generally been condemned in the diagnosis of melanoma, a deep saucerization performed by an experienced clinician can be adequate. As a surgeon, it is key to adequately review the pathologic information, because in some instances a shave biopsy is adequate, but in others a repeat biopsy may be warranted, if it would change surgical treatment planning and management. The type of biopsy performed depends on the preference of the clinician, and size and location of the lesion.

Definitive surgical management: excision margins

Preventing local recurrence and maximizing disease-free and overall survival is the primary aim of surgery. The secondary aims include preserving function and cosmesis with minimal surgical morbidity and minimal hospital stay. Hence the debate has always been about what constitutes an adequate margin width. Early teachings come from Joseph Coats and Herbert Snow in the 1880s and William Handley in the early 1900s. They advocated extensive excision of the primary tumor and a fairly radical regional lymph node dissection. This viewpoint was reinforced by Olsen’s report in 1967 in approximately 500 patients, suggesting that atypical melanocytes were often found within 5 cm of the primary melanoma. She emphasized resection with wide margins to encompass these atypical melanocytes. Local recurrence was considered more likely with narrow excision.

The understanding of local recurrence has evolved and a variety of mechanisms explain the pathogenesis of local recurrence. Incomplete excision of the original tumor or persistent disease occurs rarely with wide local excision, but is seen occasionally when anatomic constraints require narrow margin excision or when Mohs surgery is used. An alternate mechanism relates to dissemination of tumor through the intradermal lymphatics. The latter is the more common form and portends a worse overall survival. This indicates systemic involvement, and the unlikely chance that wider excision would be curative. With the understanding that depth of tumor is a bad prognostic indicator compared with the diameter, the dogma of radical wide excision was challenged.

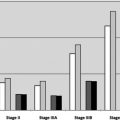

Several large retrospective studies in the 1980s indicated that the risk for local recurrence was low if the tumor was excised with 2-cm margins or more. These studies demonstrated that Breslow thickness was the most important pathologic variable to predict prognosis ( Table 2 ). One study came from the Sydney Melanoma Unit in 1985. It determined the recurrence rates in 1839 patients who underwent long-term follow-up. For thick tumors, greater than or equal to 3 mm, the local recurrence rate was 21% when the excision margin was less than 2 cm and 9% when the excision margin was 2 cm or more. For thin tumors, 0.1 to 0.7 mm, the local recurrence rates were 2% when excision margins were less than 2 cm and less than 1% when excision margins of 2 cm or more were used.