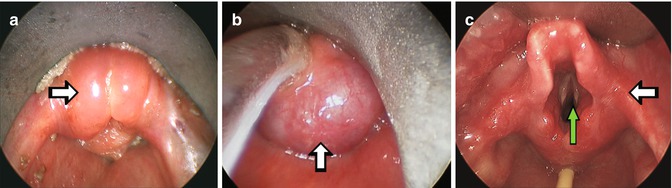

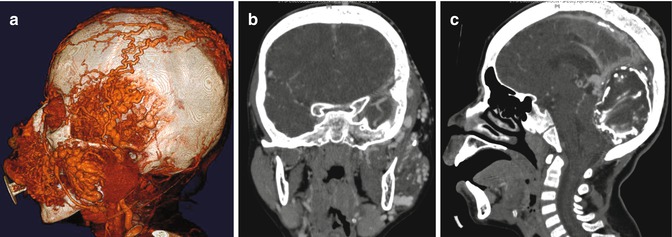

Fig. 39.1

Imaging characteristics of vascular anomalies. (a) Three-dimensional computerized tomography image of non-enhancing lymphatic malformation. (b) Axial section of same malformation. (c) Coronal section of pericranial hemangioma (arrow)

Vascular Malformation and Vascular Tumors

Vascular malformations have been separated from vascular tumors. Other vascular anomalies are seen in Table 39.1 [3]. Vascular tumors are lesions composed of vessels that demonstrate neoplastic growth. In the head and neck, this is most often a hemangioma of infancy [4]. While this discussion is limited to vascular malformations of the head and neck, many of the diagnostic and therapeutic dilemmas present in head and neck vascular tumors are also present in vascular malformations (Fig. 39.2). Vascular malformations are masses of abnormal vessels that can be present at birth or occur at any time during life. These abnormal vessels can have abnormal connections with other types of vessels, as seen in “arteriovenous” malformations (AVMs). In this situation, arteries are connected to veins prior to reaching capillaries. In lymphovenous malformations, there are abnormal connections between venous and lymphatic channels, thought to be a result of arrested separation of veins and lymph vessels. Venous and/or lymphatic malformations are often present at birth and can be detected in utero. Following detection, these lesions enlarge with the patient throughout their life. AVMs are usually detected later in life and also slowly enlarge. Local trauma to the lesion or hormonal changes during puberty can be associated with rapid malformation growth. As in any region of the body, head and neck vascular malformations can be difficult to treat due to size and location.

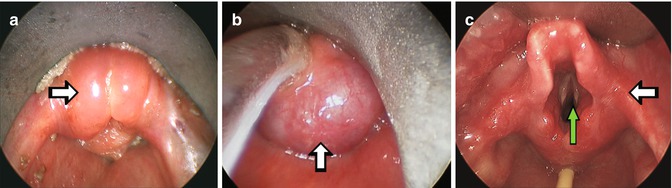

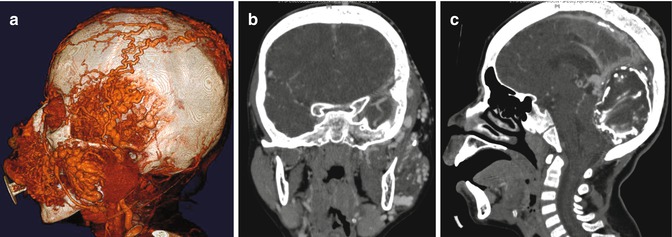

Fig. 39.2

Laryngeal involvement by vascular anomalies. (a) Epiglottis (arrow) swollen by lymphatic malformation in patient with bilateral upper neck lymphatic malformation. (b) Posterior laryngeal involvement by venous malformation (arrow). (c) Mucosal laryngeal involvement by hemangioma (white arrow), and subglottic narrowing by deep hemangioma (green arrow)

Table 39.1

Vascular anomaly classification

Vascular malformation | Vascular tumor |

|---|---|

Single vessel type | Hemangioma |

Capillary | Hemangioma of infancy |

Venous | Congenital hemangioma |

Lymphatic | Rapidly involuting congenital hemangioma (RICH) |

Arteriovenous | Non-involuting congenital hemangioma (NICH) |

Combined/complex malformations | Vascular neoplasm |

Lymphaticovenous | Kaposiform hemangioendothelioma |

Capillary-venous | Angiosarcoma |

Capillary-lymphaticovenous | Hemangiopericytoma |

Capillary-arteriovenous | Miscellaneous |

Tufted angioma | |

Pyogenic granuloma |

Considerations in Head and Neck Vascular Malformation Treatment

During evaluation and treatment of head and neck vascular malformations (HNVM), the impact of the lesion on fundamental head and neck function must be considered. Of greatest importance is airway preservation [5]. Airway compromise from vascular lesions is most commonly seen in hemangiomas of infancy (Fig. 39.3). However, vascular malformations can distort or compress any aspect of the upper airway, inducing acute airway compromise or chronic sleep disturbed breathing. Evaluation of HNVM should always include a thorough assessment of the upper airway and trachea, as any malformation swelling can induce airway compromise. The management of upper airway involvement of HNVM will be discussed in detail in Chap. 40.

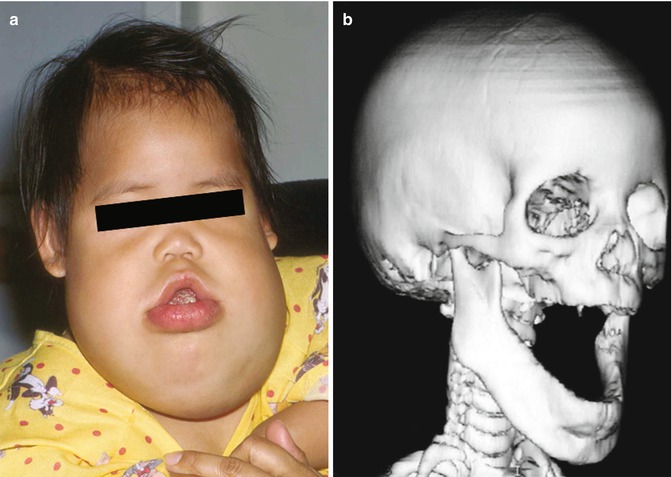

Fig. 39.3

Large low flow venous malformation involving the face and posterior cranial fossa. (a) Three-dimensional computerized tomography. (b) Coronal computerized tomography section demonstrating masticator muscle and skull base involvement. (c) Sagital computerized tomography section demonstrating large posterior cranial fossa venous malformation

Intracranial vascular malformations are often associated with HNVM [6]. Occasionally, these lesions have direct intra-extracranial communication (Fig. 39.4). These communications can compromise cerebral function, and HNVM treatment can induce cerebral injury via these communications. This is especially apparent in orbital malformations, which can impair visual function, with and without treatment. Management of orbital HNVM will be discussed in detail in Chap. 41.

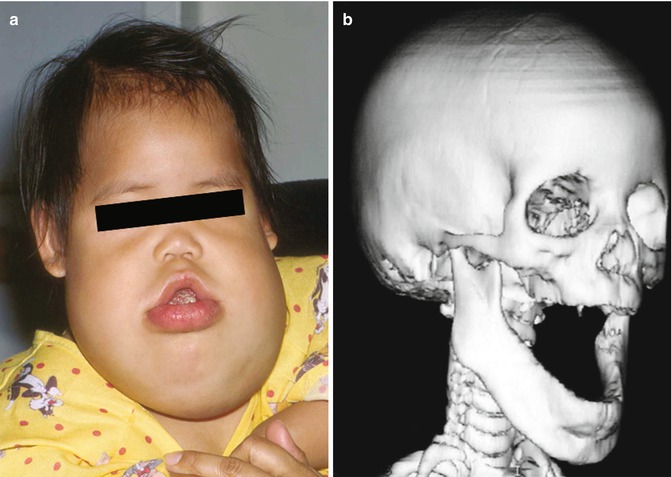

Fig. 39.4

Capillary malformation with progressive hypertrophy of soft tissue

Skull base defects from the malformation or its treatment can cause leakage of cerebrospinal fluid, increasing the possibility of meningitis. The evaluation of HNVM with high-resolution imaging techniques can detect malformations that are high risk for neurologic compromise.

The pharynx and larynx provide us with swallowing and speech capabilities, which can be affected by HNVM. Again, this can be due to the HNVM itself or its treatment. Assessment of these functions is essential in the management of HNVM, as changes in lesion size can adversely affect swallowing and speech, necessitating treatment. One of the most problematic areas is the tongue, which can be affected by any malformation.

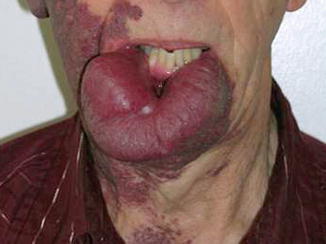

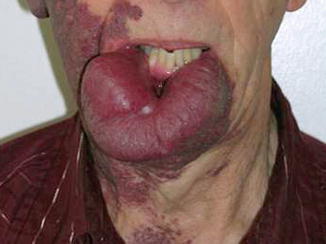

Our ability to interact with others in society is dependent on many factors; one of these is our physical appearance. In addition to causing functional changes, HNVM and their treatment often severely distort one’s appearance (Fig. 39.5). This can have a major impact on an affected individual and their family. In evaluation and management of HNVM, it is essential to monitor and treat the psychological aspects of an individual’s condition.

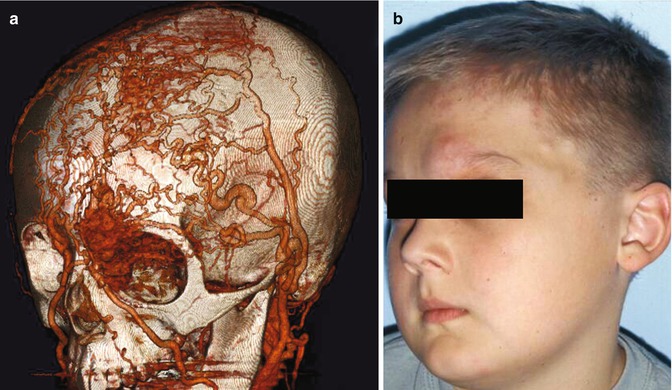

Fig. 39.5

High flow AVM of forehead, eyelid and orbit. (a) Three-dimensional computerized angiography of AVM (arrow). (b) Oblique clinical photo of affected patient

In addition to history and physical examination, HNVM need to be assessed with state-of-the-art imaging techniques, such as computerized angiography and/or magnetic resonance imaging with three-dimensional reformatting [7], to determine the full extent and physiology of the malformation (Fig. 39.6).

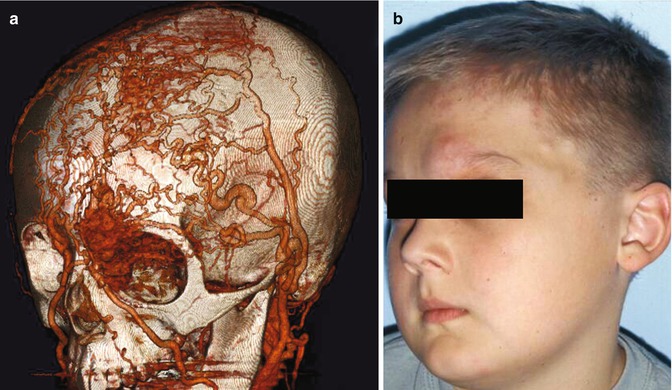

Fig. 39.6

Mandibular hyperplasia in setting of large bilateral upper neck lymphatic malformation. (a) Bilateral upper neck/ oral lymphatic malformation. (b) Three-dimensional CT of mandibular hyperplasia

Specific HNVM

Lymphatic Malformations

The most common large HNVM are lymphatic [5]. These malformations are clinically apparent at birth approximately 70 % of the time and frequently occur in the posterior neck. The other 30 % occur at any time in life in association with infection or trauma. Lymphatic malformations are low-flow lesions usually not associated with any specific syndromes, with the rare exception of Gorham-Stout syndrome, where there is skull erosion which can lead to cerebrospinal fluid leak [8]. Depending on the lymphatic malformation location, they are variably associated with soft and bony tissue hypertrophy that can adversely impact breathing, swallowing, and speech (Fig. 39.7). While lymphatic malformations are frequently associated with bony abnormalities or other systemic disease, the molecular mechanisms linking these disorders are mostly unknown [9]. Oropharyngeal and/or laryngeal involvement of the malformation can cause airway narrowing that is persistent or intermittent, as the malformation can swell intermittently with infection. When the malformation is in the orbit or near the skull base, any swelling can cause discomfort and potentially compromise function. Macroglossia is frequently associated with mandibular hypertrophy, both of which impair normal speech and swallowing function (Fig. 39.8).

Fig. 39.7

Macroglossia from microcystic lymphatic malformation

Fig. 39.8

Computerized tomography of microcystic lymphatic malformation

In addition to clinical exam findings, lymphatic malformations are diagnosed with imaging studies that describe the extent and radiographic characteristics of the lesion. More extensive lesions involving the upper neck and oral cavity are more difficult to treat. Lesions can predominantly consist of large cystic spaces (i.e., macrocystic), small cysts (i.e., microcystic), or a mixture of both [10] (Figs. 39.1 and 39.9). Often, extensive lesions have a significant venous component. Determination of lesion extent and radiographic characteristics is essential in treatment planning and patient counseling.