Historically, women who present with stage IV metastatic breast cancer (MBC), even those with an intact primary tumor, are not offered surgical treatment. Instead, the recommended primary treatment approach is systemic therapy. However, improved breast cancer screening and imaging technology have presented a different dilemma: patients with MBC may have oligometastatic or stable metastatic disease with an operable intact primary tumor, suggesting that surgery may be effective. Furthermore, over the past 25 years, multimodality treatments for new and advanced breast cancers have resulted in improved median survival times for patients with MBC.1 Therefore, for patients with MBC, it is time to reevaluate the role of resection of the intact primary tumor and the role of metastasectomy in patients without an intact primary tumor.

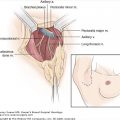

It is generally accepted that mastectomy does not confer a survival advantage after metastases have developed.2 Surgical treatment of intact primary tumors in patients with MBC has generally been reserved for palliation, such as treatment of bleeding, tumor ulceration, infection, or hygienic conditions. A salvage, or “toilet,” mastectomy is generally performed as a last resort, with no intent for cure. However, multiple national databases and single-institution studies in the past 8 years have reexamined the role of resection of intact primary tumors for patients with MBC to clarify its role in the care of breast cancer patients (Table 72-1).3-8

| Investigator | Study Period | Type of Study | Number of Patients Who Underwent Resection | Number of Patients Who Did Not Undergo Resection | Primary End Point | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Khan et al3 | 2002 | NCDB | 6861 | 9162 | Time to death |

|

| Rapiti et al4 | 2006 | Geneva Cancer Registry | 127 | 173 | 5-year breast cancer–specific survival |

|

| Babiera et al5 | 2006 | Single institution | 82 | 142 |

| No surgery: NA Surgery: PFS, HR = 0.54, p < .007 OS: HR = 0.5, p < .12 |

| Fields et al6 | 2007 | Single institution | 187 | 222 | Overall survival |

|

| Gnerlich et al7 | 2007 | SEER program data | 4578 | 5156 | Overall survival | Median survival = surgery 36 months vs no surgery 21 months, p < .001 |

| Blanchard et al8 | 2008 | Single institution | 242 | 153 | Overall survival | Median survival = surgery 27.1 months vs no surgery 16.8 months, p < .0001 |

Retrospective studies addressing the role of resection of the intact primary tumor for patients with MBC have shown an association with improved survival and metastatic disease-free survival (DFS). The best results have been observed in patients with negative surgical margins and only bone metastases.6,8 However, in several of the studies, the data are limited on the tumor characteristics that are associated with prognosis and on the use of adjuvant therapy, such as chemotherapy, hormonal therapy, and radiation therapy. This lack of information and the confounding effects of the multimodality therapies used in breast cancer treatment make it difficult to interpret the results and discern the value of surgical intervention. Furthermore, given the retrospective nature of these studies, there is little information about the clinical criteria used in deciding which patients underwent surgery and which did not.

In order to design a clinical trial many important questions regarding surgery in patients with MBC still remain unanswered: When is the best time to resect the intact primary tumor from these patients? What are the effects of systemic chemotherapy and local radiation therapy? What is the role of axillary surgery? What criteria should be used to decide whether resection of the intact primary tumor should be performed?

Unfortunately, to date, only 1 study has addressed the question of the best time to resect the intact primary tumor in patients with MBC. Rao et al performed a retrospective review of all patients with breast cancer who were treated at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center between 1997 and 2002 and who presented with an intact primary tumor and synchronous metastatic disease.9 A multivariate analysis revealed that patients who had only 1 site of metastasis (p = .024) and negative margins upon resection of the primary tumor (p = .013) and who were white (p = .004) had longer progression-free survival (PFS) times than other patients. Interestingly, further analysis revealed that non-Caucasian patients more often underwent resection for palliative indications than for curative intent, which could explain these patients’ worse outcomes. Patients who underwent surgery 3.0 to 8.9 months or later after diagnosis had longer metastatic PFS. Rao et al concluded that surgical extirpation of the primary tumor in patients with MBC was associated with longer metastatic PFS when performed more than 3 months after diagnosis. However, it was not clear whether the longer metastatic PFS resulted from the surgery or was a reflection of the added benefit of systemic chemotherapy.

Because of the limitations associated with retrospective studies, and the fact that these are the only types of studies that have been performed to determine the value of resection of an intact primary tumor in patients with MBC, the most important question still remains unanswered: Does resection of an intact primary breast tumor really improve survival in patients with MBC?10 Or do these results reflect a selection bias? To conclusively answer this question, a prospective, randomized clinical trial needs to be conducted. Fortunately, 2 prospective trials on local therapy in patients with MBC have already been initiated outside of the United States.11 One trial started in February 2005 in India (NCT00193778), and the second trial started in November 2007 in Turkey (NCT00557986). The trial in India is being conducted at the Tata Memorial Hospital and is randomizing patients who responded to 6 cycles of chemotherapy into 2 groups: surgery and no surgery. The Turkish trial is randomizing patients to surgery or no surgery before receiving any systemic therapy. In the meantime, until data are available from these prospective trials, surgery may be considered for select stage IV patients with oligometastatic or stable metastatic disease with an operable intact primary tumor.

Breast cancer most commonly metastasizes to bone, followed by the lungs, brain, and liver.12 Up until now, the treatment focus for MBC has been on palliative care rather than cure. However, a more aggressive and potentially curative treatment approach may be adequate for patients with MBC limited to a solitary metastasis or to multiple metastases at a single organ site.13 In selected patients with MBC with a controlled primary tumor (typically those treated previously), a long disease-free period, and good performance status, resection of the distant metastatic sites (metastasectomy) might be a viable option. The main goal of metastasectomy would be improved quality of life and prolonged DFS in these patients, although, as noted, cure may also be possible.

The most common first site of breast cancer metastases is bone. Patients with only bone metastases have been reported to have a more favorable prognosis and a more “indolent” course14 than patients with bone metastases and additional visceral metastases. In addition, patients with solitary bone metastases have a 39% chance of being alive after 5 years.15,16 Bone metastases have been reported to occur more frequently in certain types of breast cancers. Recent data have shown that luminal A breast cancers are more likely to metastasize to bone than basal-type cancers.17

Treating bone metastases is crucial, as bone metastases may result in considerable skeletal-related morbidity from bone pain, fractures, spinal cord compression, or hypercalcemia. In weight-bearing bones, bone metastases can lead to problems of mobility. In addition, spinal cord compression can occur and can be an acute life-threatening complication.13 Usually, the first treatment option for bone metastases on bones that are not at risk of fracturing is either endocrine- or chemotherapy-based systemic therapy. The incidence of bone metastases is increasing as patients with breast cancer are living longer.18

Surgery is most frequently used for treating long bone metastases and femoral fractures.19 The goals of relieving pain and restoring mobility may be accomplished by a variety of surgical techniques. Prophylactic surgical fixation for lytic lesions has been recommended for lesions of the cortex that are larger than 2.5 cm in size, lesions involving more than 50% of the bone diameter, or lesions that are painful despite prior radiation therapy. In addition, Weber et al advocates using adjuvant radiation therapy for all patients with surgically treated bone metastases.18 For these patients, the standard radiation dose used is 30 Gy, with few side effects seen.20 Postoperative radiation therapy should start 10 to 14 days after surgery to allow wound healing. Epidural spinal cord compression is an oncologic emergency often heralded by increasing pain in a patient with known vertebral metastases. Early diagnosis is the key to maintaining neurologic function because once neurologic deficiencies are present, surgery is rarely performed and functional improvement is unlikely.21

Sternal bone metastases should be considered to be in a different category than vertebral bone metastases. Since the sternum lacks communication with the paravertebral venous plexus, through which cancer cells spread easily to other bones, sternal metastases seem to remain solitary for a longer time.22 Noguchi et al studied 9 patients with solitary sternal metastases from breast carcinoma who were treated aggressively with partial or total resection of the sternum. The median survival time in all 9 patients was 30 months. The prognosis of the patients who also had mediastinal or parasternal lymph node metastases was poor, and all of these patients died because of a second relapse within 30 months. The prognosis of patients without mediastinal or parasternal lymph node metastasis was quite favorable (3 of them survived more than 6 years). From their study, they concluded that sternectomy should be indicated for the solitary sternal metastasis when no evidence of systemic spread is noted since it can improve the quality of life and occasionally may result in long-term survival. In addition, improvements in surgical techniques, especially by means of myocutaneous flaps and prosthetic materials, have resulted in safe, successful sternectomies and simultaneous reconstructions.23

Isolated pulmonary metastases have been reported to occur in 10% to 20% of all women with breast cancer.24 Approximately, 3% of all women with breast cancer develop a solitary pulmonary lesion detectable by chest radiography, of which 33% to 40% will be breast cancer metastases.25,26 Considering the low morbidity and mortality rates associated with pulmonary metastasectomy, it can be considered in selected patients with pulmonary metastases from breast cancer.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree