IIB

T3N0M0

A reasonable initial surgical approach is likely to achieve pathologically negative margins and provide long-term local control

Primary operable

IIIA

T3N1M0

IIIA

T0N2M0

T1N2M0

T2N2M0

An initial surgical approach is unlikely to successfully remove all disease or to provide long-term local control

Primary inoperable

IIIB

T4N0M0

T4N2M0

IIIC

Any TN3M0

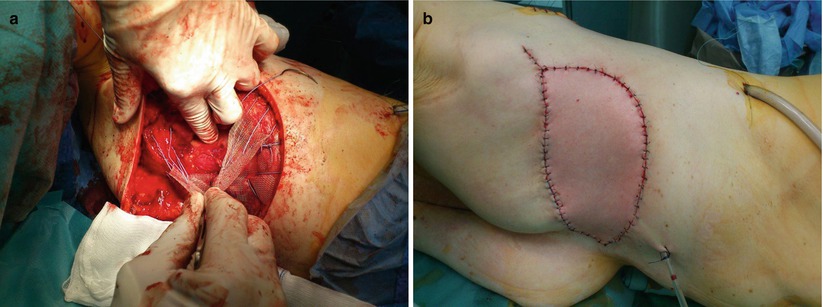

«Inflammatory breast cancer (IBC)» (◘ Fig. 54.1a) is a clinicopathologic entity different from «noninflammatory LABC» (◘ Fig. 54.1b). The very specific nature of the disease renders classification attempts difficult. However, some investigators have classified IBC into three separate groups: [1] IBC with clinical features only, [2] IBC with clinical and pathologic features and [3] IBC with pathologic features only. Other clinical varieties which have been identified, and are commonly cited, include «primary IBC» used to describe the de novo development of IBC in a previously healthy breast and «secondary IBC» used for development of inflammatory skin changes mimicking primary IBC in a breast earlier treated for cancer or on the chest wall after mastectomy for non-IBC [7].

Fig. 54.1

a Inflammatory breast cancer; b Noninflammatory locally advanced breast cancer

54.3 Management of Locally Advanced Breast Cancer and Inflammatory Breast Cancer

Management involves careful coordination of all multidisciplinary modalities, including imaging, systemic chemotherapy, surgery and radiation therapy. The use of neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NAC) has contributed significantly to improvements in overall survival (OS) since the first descriptions of this treatment and has made the role of locoregional therapy, including surgery and radiation, critical to continued improvements in outcome for this disease [8].

Locoregional treatment is based on a combination of systemic therapy, surgery and radiotherapy. In the multidisciplinary team, the role of the surgical oncologist is to localise the tumour, clarify the goals of NAC and ensure appropriate imaging before and after the treatment. An image-guided metallic clip should be placed in the tumour pre-neoadjuvant chemotherapy in patients potentially eligible for breast-conserving surgery (BCS) to permit surgical localisation, as well as in those for whom mastectomy may be required, to assist in location of the primary site by the pathologist which is especially important in cases which undergo a good partial or complete response. It can also be placed during systematic treatment, when significant regression in tumour size is observed [9]. This practice is advised especially in small and rapidly regressing tumours, while it may be omitted in patients with large and nonresponsive cancers which are more likely to have residual disease after NAC.

In patients not responding to neoadjuvant treatment, second-line chemotherapy, preoperative radiotherapy or salvage mastectomy should be discussed by the team. Sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) could be considered for patients with clinically negative axillary lymph nodes before chemotherapy. For patients with node-positive disease, axillary lymph node dissection should be performed although this is a subject of current research interest and is discussed in more detail in ► Chap. 25 [10]. Patients with inflammatory breast cancer should always undergo ANC as SLNB is contraindicated.

In patients with IBC, general recommendations are similar to noninflammatory LABC and include NAC as the treatment of choice. First-line chemotherapy must be followed by mastectomy with axillary clearance in most cases, even for patients who have responded well to chemotherapy. Immediate breast reconstruction (IBR) is not recommended. Surgery must be followed by radiotherapy to the chest wall and axilla, even when complete response was achieved with chemotherapy. Local relapse in patients with IBC is almost always followed by distant metastases and death [11].

54.4 Mastectomy after NAC

Before consideration is given to the type of surgery to be offered after NAC, it is worth considering whether surgery of any sort has oncological benefit in the LABC setting. There have been a number of studies which have failed to show any survival or local control benefits from combining surgery and chemotherapy when patients with a poor response to systemic treatment are included in the analysis. In contrast patients with a good response to NAC demonstrate both enhanced long-term survival and improved disease-free survival (DFS) after undergoing mastectomy [25].

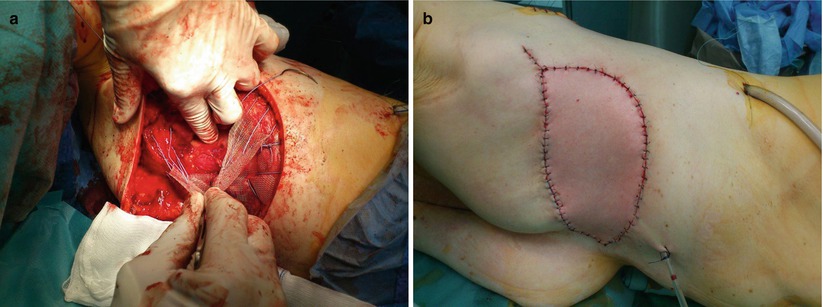

The role of mastectomy in the treatment of LABC is traditional and obligatory in some cases such as IBC where the dermal lymphatics are permeated with tumour. In such cases skin-sparing mastectomy is contraindicated as well. In cases of IBC, there is a need to resect the currently or previously involved skin at the time of mastectomy. Increased wound and skin flaps tension after mastectomy must be avoided as it may delay the start of radiotherapy significantly. If necessary, repair with an autologous tissue flap is preferable to achieve tension-free closure, for example, with a latissimus dorsi myocutaneous flap or a thoracodorsal artery perforator flap (TDAP) unless extremely broad coverage is needed [8]. In cases where an extremely wide defect is likely, a muscle-only LD flap with skin grafting may be used (or a DIEP flap may be used). Caution is needed if applying a split-thickness skin graft to achieve skin closure as subsequent radiotherapy may damage the skin graft (◘ Fig. 54.2a, b).

Fig. 54.2

a Resection of the thoracic wall with mesh and LD flap reconstruction – intraoperative; b Resection of the thoracic wall with mesh and LD flap reconstruction – postoperative

In cases with chest wall invasion, if this is confined to the musculature (pectoralis, serratus anterior), it is easy to excise the muscle en bloc with the mastectomy specimen. However, deeper invasion of the thoracic wall is a much more significant issue. Primary or secondary tumours infiltrating the ribs and sometimes the sternum require broad resection of ribs, partial sternectomy and occasionally resection of endothoracic organs. Chest wall reconstruction after such resections is performed using different types of prosthesis (surgical mesh, combined prosthesis with methyl metacrylate) covered with vascularised pedicle muscle flaps, most commonly LD and TRAM. Ulceration of the chest wall due to radiation necrosis can also be resected by these techniques, contributing to patient comfort and well-being [12].

Recently Italian surgeons published a study of 40 patients treated surgically with chest wall resection for recurrent breast cancer reaching a 5-year overall survival of 68.5% [13]. The best survival rates were achieved in younger patients without synchronic metastatic disease, not requiring additional post-resection treatment.

54.5 Mastectomy Versus Conservation Surgery in LABC after NAC

The study of the oncologic safety of breast-conserving surgery compared to mastectomy in patients receiving NAC for LABC demonstrated that it is a safe option for cases which responded well to NAC. Shrinking the tumour with NAC allows for breast-conserving surgery without compromising optimal oncologic outcomes [14, 15]. In a large NSABP B-18 study, no significant differences between mastectomy and BCT with regard to the primary end points of OS, DFS and relapse-free survival were found [16].

In operable cancers NAC improves the rate of breast-conserving surgeries, particularly among tumours >5 cm; however the risk of local recurrence in the conserved breast increases with this approach [17]. Given the good efficacy of antihuman epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2)-based neoadjuvant systemic treatment, breast-conserving surgery should be standard practice for most patients. It can be offered after NAC if the following selection criteria are met: complete resolution of skin oedema, residual tumour size <5 cm, no evidence of multicentricity and absence of extensive intramammary lymphatic invasion/extensive microcalcification [18]. The rate of conservative surgery will be higher in patients with a complete or partial clinical response, treated at specialised centres with experience in administering such treatments [19].

When feasible, oncoplastic techniques may be offered in LABC patients. Its usage does not affect oncological safety or local control after surgery. On long-term follow-up, no survival or local control issues were observed. Cosmetic outcomes were also acceptable at 5-year follow-up [20]. Therefore selected stage III breast cancer patients can be safely offered oncoplastic surgery. If a good response to neoadjuvant treatment is achieved, breast-conserving surgery can be performed with acceptable complication rates, local recurrence rates, good aesthetic and quality of life result [21]. In these patients oncoplastic surgical techniques decrease the rates of radical surgery despite the presence of initially large tumours [22].

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree