Gynecomastia (GM) is a benign proliferation of the glandular component of the male breast caused by an increase in the ratio of estrogens to androgens. It presents as a palpable, concentric, and often painful subareolar mass and may be unilateral or bilateral. Although the finding of breast enlargement may be embarrassing or distressing to the patient, surgery for GM is rarely indicated, and cancer is present in less than 1% of patients. Gynecomastia is common. Two historical case series report 57% of healthy older men have GM, which increases to nearly 70% in hospitalized older men.1,2 Further, autopsy series found GM in 40% to 55% of unselected cases.3

Gynecomastia occurs physiologically with 3 natural peaks—in the neonatal period, puberty, and senescence. During the neonatal period, 60% to 90% of infants have transient breast enlargement due to maternal estrogen influence. By puberty, 50% to 75% of boys experience breast enlargement as estrogen concentrations peak earlier than the nearly 30-fold increase in testosterone concentrations.4 Most GM related to puberty spontaneously regresses within 2 years. Finally, as men age, free testosterone levels decline and obesity becomes more prevalent, increasing relative estrogen concentrations and therefore the incidence of GM.

Although GM is often physiologic, it may be idiopathic or associated with more serious disease, congenital syndromes, and/or medications (Tables 70-1 and 70-2).5 All result in either an increase in estrogen, decrease in androgen, or a deficit in androgen receptors. Nearly 75% of men seeking evaluation have idiopathic GM, persistent GM after puberty, or drug-induced GM.6

| Pathologic | |

|---|---|

| Androgen insensitivity syndromes | |

| Congenital syndromes | Klinefelter syndrome |

| Genetic mutation in aromatase gene | |

| Neurologic disease | Spinal cord injury |

| Primary or secondary gonadal failure | |

| Starvation and refeeding | |

| Systemic illness | Liver or renal failure |

| Thyroid disease | |

| True hermaphroditism | |

| Tumors | Adrenal, colon, lung, liver, pituitary, prostate, testicular (Leydig, Sertoli, and germ cell) |

| Drugs | |

|---|---|

| Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors | |

| Amiodarone | |

| Anabolic steroids or testosterone replacement | |

| Androgen receptor blockers | Flutamide, finasteride |

| Calcium channel blockers | |

| Cytotoxic chemotherapeutics | Vincristine, methotrexate |

| Gonadotrophin-releasing hormone agents | |

| Estrogen containing cream or cosmetics | |

| H2 antagonists and proton pump inhibitors | |

| Isoniazid | |

| Ketoconazole | |

| Marijuana and heroin | |

| Metronidazole | |

| Phytoestrogens: soy products, beer | |

| Spironolactone | |

| Theophylline | |

| Tricyclic antidepressants |

The etiology of GM is frequently ascertained simply by comprehensive clinical evaluation, including history and physical examination. Attention must be given to a complete review of systems and medication evaluation. Frequently in long-standing GM no further evaluation is necessary. Gynecomastia of recent onset typically presents as a tender, smooth, mobile, rubbery mass centrally within the breast with a normal appearance to the overlying skin, nipple, and areola. In contrast, breast cancers are hard, ill-defined masses, and they may be associated with skin flattening or retraction. Nipple bleeding or discharge may be present in up to 10% of men with breast cancer.7 Gynecomastia can be unilateral or bilateral, and although unilateral GM must be differentiated from breast cancer, the overwhelming proportion of unilateral breast masses in men are benign. However, the physical findings of GM and early breast cancer may be quite similar, and any persistent breast mass of recent onset requires further evaluation.

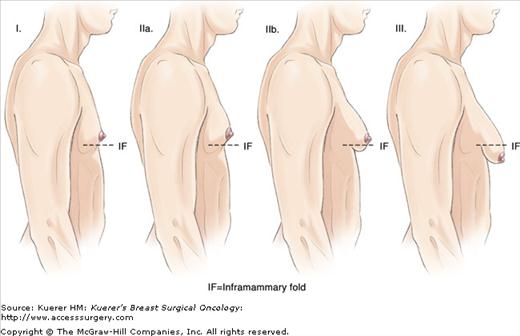

Many classification systems categorize GM with only slight variation in definition.8-10 Only Rohrich10 attempts to quantify breast tissue volumes preoperatively. None is used routinely in practice, and none is standardized in published literature. Practically, the most useful grading scale may be one that incorporates breast size, shape, and the anatomic findings that will affect surgical decision making. Although identification of breast enlargement is important for diagnosis, features such as nipple location in reference to the inframammary fold, degree of breast ptosis, and quantity of skin redundancy are important considerations when determining the appropriate surgical procedure for these patients. In general, the grades of GM are as follows9 (Fig. 70-1):

- Grade I: small visible breast enlargement without skin redundancy

- Grade IIA: moderate breast enlargement without skin redundancy

- Grade IIB: moderate breast enlargement with skin redundancy

- Grade III: marked breast enlargement with skin redundancy and ptosis

Figure 70-1

Line drawing illustration of the grades of gynecomastia. Grade I: profile view of a breast bud with prominence only in the retroareolar location. Grade IIA: profile view with larger prominence in retroareolar location. Grade IIB: same as IIA but also with visible inframammary fold. Grade III: larger than IIB, visible inframammary fold, and ptosis with nipple at or below the inframammary fold.

Gynecomastia can be classified into 2 histologic types based on morphologic features: the florid type and fibrous type. The florid type exhibits epithelial cell hyperplasia, stromal edema, and increased cellularity. This proliferative phase is composed of ≥2 cell layers often with fingerlike projections extending into the ductal lumen. The fibrotic type of GM is characterized by dense fibrous, acellular stroma, atrophic glands, and scattered ducts with a minimal degree of proliferative activity.

Mammography is reasonable in most men under evaluation for GM surgery, and particularly if there is any suspicion of cancer. In the setting of a known tissue diagnosis, mammography has a sensitivity of 90% and a specificity of 92%, respectively,11 but it is limited by a positive predictive value of 55%. In the setting of clinical symptoms, the benefit is less clear. Among 198 men with breast symptoms (tenderness, mass, tender mass, nipple sensitivity, nonspecific breast enlargement) 203 of 212 mammograms (96%) demonstrated benign findings.12 The authors concluded that mammography adds little to the initial comprehensive male breast evaluation. As in women, mammography in men can be falsely negative and should not be taken as reassurance in the setting of a dominant breast mass.13,14 The role of ultrasound in the evaluation of GM is less clear because findings include a hypoechoic mass with irregular margins in up to 80% of benign GM cases.13 No evidence supports the use of magnetic resonance imaging in the evaluation of GM.

Fine-needle aspiration of male breast masses can be helpful, with a reported negative predictive value greater than 95% and a positive predictive value of 100%.15 However, this technique requires an experienced cytopathologist and can be associated with a high rate of unsatisfactory (acellular) specimens, especially when the GM has a prominent component of stromal fibrosis.16

Although patients with physiologic GM frequently seek evaluation, few seek additional treatment when reassured that symptoms are transient and usually regress.4 Most patients with nonphysiologic GM usually require no treatment. Most resolve spontaneously within a few months or with the removal of precipitating factors. Specific treatment is indicated only when symptoms of breast enlargement are persistently painful, embarrassing, or distressing to the patient and negatively affect his overall quality of life. There is little role for medical treatment, which is only effective during the early proliferative phase before the development of stromal hyalinization and fibrosis.17 Surgical treatment of GM aims to reduce breast size, alleviate symptoms, and restore the chest contour. The most commonly employed techniques are local excision, liposuction, or subcutaneous mastectomy. Techniques such as breast reduction, mastopexy, and free nipple grafting or revision can be added as primary or secondary procedures depending on degree of skin redundancy and nipple location.

When possible, incisions should be either circumareolar or in a remote lateral position for the best cosmetic results. Extension of the incision within the pigmented areola may result in a white line as it scars, whereas those placed on the skin may result in a hypertrophic scar in 5% to 10% of cases.18 Surgical markings should be made preoperatively with the patient awake in the upright position because the exact position of the areolar border may be difficult to find especially after the injection of tumescent solutions or local anesthetics containing epinephrine.