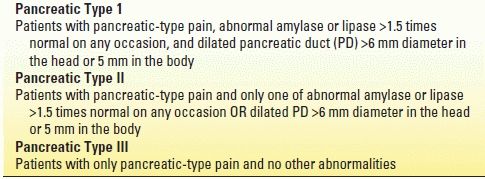

TABLE 24.2 Modified Pancreatic Classification System for Sphincter of Oddi Dysfunction

EPIDEMIOLOGY

SOD most commonly occurs in middle-aged females, although patients of any age or sex may be affected. Although SOD typically is seen in the postcholecystectomy state, it may occur with the gallbladder in situ. The epidemiology of SOD is unclear due to a paucity of population-based data and the considerable variation that exists in currently published literature, including patient selection criteria, definition of SOD used, and whether or not one or both sphincter segments are studied by sphincter of Oddi manometry (SOM). Eversman et al. performed SOM of both the biliary and pancreatic sphincter segments in 360 patients with intact sphincters. In this series, 19% had abnormal pancreatic basal sphincter pressure alone, 11% had abnormal biliary basal sphincter pressure, and 31% had abnormal basal sphincter pressure in both segments (total 61% with abnormal SOM). A more recent 14-year review of patients undergoing evaluation with SOM at our institution identified SOD in 65% of patients. These and other studies highlight the need to evaluate both the bile duct and pancreatic duct during SOM. Sphincter dysfunction may also cause recurrent pancreatitis, and manometrically documented SOD has been reported in 15% to 72% of patients previously labeled as having idiopathic pancreatitis.

PATHOGENESIS AND PATHOLOGY

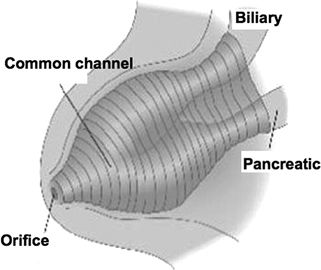

The SO is a complex of smooth muscles that surrounds the terminal common bile duct, ventral pancreatic duct, and the common channel (ampulla of Vater) if present (Fig. 24.1). Its primary role is to regulate bile and pancreatic juice flow and to prevent reflux of duodenal contents into the sterile biliary and pancreatic systems. The SO has both a variable basal pressure and phasic contractile activity, which are under both neural and hormonal control. Patients with type I SOD are thought to have a stenotic sphincter rather than a sphincter in spasm, as pathologic series of sphincteroplasty resection specimens have shown significant inflammation, reactive muscular hypertrophy, and fibrosis within the papillary zone in 60% of patients. These pathophysiologic changes at the sphincter papillary orifice are likely responsible for ductal hypertension with resultant duct dilation, elevated liver enzymes, and biliary-type pain in patients with type I SOD. In patients with type II and III SOD, the mechanism of dysfunction is not related to sphincter inflammation and scarring but is thought to be related to dysregulation of stimulatory and/or inhibitory factors.

FIGURE 24.1 The sphincter of Oddi.

How does SOD cause pain? From a theoretical point of view, this may be related to (a) impedance of flow of bile and pancreatic juice resulting in ductal hypertension, (b) muscular ischemia of the sphincter arising from spastic contractions, and (c) hypersensitivity of the papilla and/or duodenum. These mechanisms may potentially act alone or in concert to explain the genesis of pain.

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

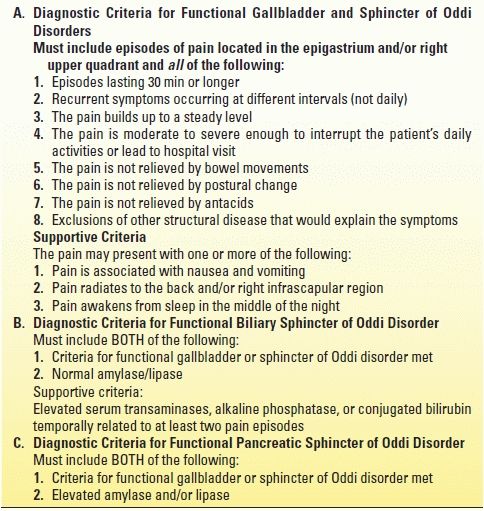

The Rome III classification system has provided diagnostic criteria for SOD (Table 24.3). Abdominal pain is the most common presenting symptom. The pain is usually localized to the epigastric area or right upper quadrant, may radiate to the back or shoulder, and lasts anywhere from 30 minutes to several hours. Pain may be precipitated by food or narcotics and often is accompanied by nausea and vomiting. The pain may begin several years after cholecystectomy and is usually similar in character to the pain that initially prompted gallbladder evaluation. Alternatively, patients may have continued pain that was not relieved by cholecystectomy. Jaundice, fever, or chills are rarely observed. Physical examination typically is negative or reveals only mild abdominal tenderness. The pain is not relieved by trial medications for acid peptic disease or irritable bowel syndrome. Laboratory abnormalities consisting of transient elevations of liver tests during episodes of pain that normalize during pain-free periods may be observed. Patients with pancreatic SOD may present with typical pancreatic pain with or without pancreatic enzyme elevation or recurrent pancreatitis.

TABLE 24.3 Rome III Criteria for Functional Biliary, Gallbladder, and Sphincter of Oddi Disorders

Adapted from Behar J, Corazziari E, Guelrud M, et al. Functional gallbladder and sphincter of Oddi disorders. Gastroenterology 2006;130:1498–1509.

The association between SOD and chronic pancreatitis is poorly understood. It is not known whether the sphincter at times becomes dysfunctional as part of the overall scarring process or whether it has a role in the pathogenesis of chronic pancreatitis. However, a high frequency of basal sphincter pressure abnormalities in the pancreatic sphincter has been identified, with 20 of 23 (87%) chronic pancreatitis patients found to have SOD in one study. Sphincterotomy has been demonstrated to improve pain in a subset of patients with chronic pancreatitis in uncontrolled studies.

While the diagnosis of SOD is commonly made after cholecystectomy, SOD may also exist in the presence of an intact gallbladder. However, the symptoms due to SOD may be indistinguishable from gallbladder-type pain, resulting in the diagnosis of SOD being made after cholecystectomy or less frequently after gallbladder abnormalities have been excluded. Given the potential complications of ERCP in patients with suspected SOD (see below), empiric cholecystectomy may be considered in select patients as initial therapy prior to ERCP even in the setting of normal gallbladder evaluation.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

The clinical presentation of SOD may be mimicked by many organic pathologies including common bile duct stones, chronic pancreatitis, ampullary tumors, peptic ulcer disease, mesenteric ischemia, renal colic, as well as other functional disorders including irritable bowel syndrome, referred musculoskeletal pain, and functional dyspepsia. Because of the 10% to 20% complication rate seen in the evaluation and therapy of patients with suspected SOD (see below), the diagnosis should be treated as one of exclusion, with other diagnostic possibilities initially pursued with appropriate testing. As well, therapeutic trials with low-risk empirical medical therapies such as proton pump inhibitors, antispasmodics, and/or pain modulators should be made before proceeding with ERCP and SOM.

Diagnostic Methods

Initial investigations for patients with suspected SOD should include laboratory tests (liver enzymes, serum amylase and/or lipase) and abdominal imaging (ultrasound or computed tomography (CT) scan). If at all possible, the enzyme studies should be drawn during an acute attack of pain, although liver test abnormalities lack both sensitivity and specificity. Mild elevations (<2× upper limit of normal) are common in SOD, whereas greater abnormalities are more suggestive of stones, tumors, and intrinsic liver disease. Imaging of the abdomen is usually normal, but occasionally dilated bile ducts or pancreatic ducts may be found (type I or type II patients). More detailed structural evaluation may be obtained with EUS and MRI/MRCP in select patients. Several noninvasive tests have been designed in an attempt to identify those individuals with SOD. The morphine–prostigmine provocative test (Nardi test) has been shown to have an unacceptable rate of false-positive studies (>40% in patients with irritable bowel syndrome) and as such is no longer recommended. Quantitative hepatobiliary scintigraphy (HBS), with or without morphine provocation, may predict an abnormal SOM and response to biliary sphincterotomy. However, abnormal results may be found in asymptomatic controls, and HBS does not address the pancreatic sphincter, which may be the cause of the patient’s symptoms. Measurement of common bile duct diameter by ultrasound after either lipid-rich meal or secretin stimulation has also been shown to have variable sensitivity (21% to 88%) and specificity (82% to 97%). Our group has prospectively compared secretin-stimulated MRCP (sMRCP) to SOM. Prediction of SOD based on sMRCP results was poor, with positive and negative predictive values of 67% and 33%, respectively. Considering the limitations of noninvasive testing, SOM demonstrating an elevated basal sphincter pressure greater than 40 mm Hg (either biliary or pancreatic) is still considered the gold standard for diagnosing SOD.

Performance of SOM

SOM is the only available method to measure SO motor activity directly and is considered by most authorities to be the most accurate evaluation for sphincter dysfunction. Although SOM can be performed intraoperatively and percutaneously, it is most commonly done in the ERCP setting. The use of manometry to detect motility disorders of the SO is similar to its use in other parts of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. However, performance of SOM is more technically demanding and hazardous, with complication rates (in particular, pancreatitis) approaching 20% in several series. Its use, therefore, should be reserved for patients with clinically significant or disabling symptoms. One needs to appreciate, however, that SOM is not likely an independent risk factor for post-ERCP pancreatitis when the aspirating manometry catheter is used. It is the suspicion of SOD itself rather than the performance of SOM that places the patient at increased risk.

The initial step in performing SOM is to administer adequate sedation, which will result in a comfortable, cooperative, motionless patient. All drugs that relax (anticholinergics, nitrates, calcium channel blockers, glucagon) or stimulate (narcotics, cholinergic agents) the sphincter should be avoided for at least 8 to 12 hours prior to SOM and during the manometric session. SOM requires selective cannulation of the bile duct and/or pancreatic duct. It is preferable to perform cholangiography and/or pancreatography prior to performance of SOM, as certain findings (e.g., bile duct stones) may obviate the need for SOM. Once deep cannulation is achieved and the patient acceptably sedated, the catheter is withdrawn across the sphincter. Ideally, both the pancreatic and bile ducts should be studied. Current data indicate that an abnormal basal sphincter pressure may be confined to one side of the sphincter in 35% to 65% of patients with abnormal manometry, and thus, one sphincter segment may be dysfunctional and the other normal. An abnormal basal sphincter pressure is more likely to be confined to the pancreatic duct segment in patients with pancreatitis and to the bile duct segment in patients with biliary-type pain and elevated liver function tests.

Most authorities use only the basal sphincter pressure as an indicator of pathology of the sphincter of Oddi, with 40 mm Hg used as the upper limits of normal for mean basal sphincter pressure (mean value plus three standard deviations). Interobserver variability for reading SOM is minimal when the observers are experienced in reading these tracings.

It has been questioned whether the short-term pressure recording obtained during SOM reflect the “24-hour pathophysiology” of the sphincter, as patients with SOD may have intermittent, episodic symptoms. If the basal sphincter pressure does vary over time, performance of SOM on two separate occasions may lead to different results and affect therapy. Three studies have demonstrated reproducibility of biliary SOM in 34 of 36 symptomatic patients overall and 10 of 10 healthy volunteers. However, reproducibility of pancreatic SOM was found in only 58% (7/12) and 40% (12/30) of persistently symptomatic patients with previously normal SOM at two large referral centers. Other studies have also shown that SO basal pressures are not constant, perhaps due to the inherent physiologic fluctuation of SO motor activity. Newer devices capable of portable, ambulatory, prolonged SOM would be of interest.

THERAPY FOR SPHINCTER OF ODDI DYSFUNCTION

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree