Advances in cancer detection and early diagnosis, more effective treatments, and the adoption of healthier lifestyles by those at risk for cancer have resulted in a dramatic increase in the number of individuals living longer with their cancer. In many instances, cancer has become a survivable illness. Cancer survivors constitute 3.5% of the United States population, but second primary malignancies among this high-risk group now account for 16% of all cancer incidence.

1 The 5-year survival for many cancer sites exceeds 50%, suggesting that these patients are living longer and may be considered to have a chronic illness.

2 Cancer survivors are high health care utilizers affecting distinct health care domains owing to therapeutic exposures, genetic predisposition, and/or lifestyle risk factors.

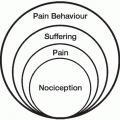

Improved quality of life (QoL) is the goal of survivorship. Survivors should understand the importance of pain control as a vital component of this process. Patient, professional, and system-related barriers that are seen during active treatment may continue to hinder optimal pain relief during survivorship.

3 For clinicians to be understanding of the very complex needs of patients with cancer, it is requisite that they be aware of often unspoken expressions of a patient’s anxieties about pain and suffering, loss of control over personal destiny, dread of dying and of the end of cherished relationships.

4New pain complaints or side effects from treatment (ie, pharmacotherapeutic or cancer treatment) require careful evaluation and management. Survivors and families need to understand their fundamental role as part of the treatment team and that successful survivorship may be dependent on their sharing any concerns or fears related to pain management. Educational tools that are easy to read and understand should be available for all patient populations. Health care providers should work to educate not only survivors and families who are currently in treatment, but also the entire community of the availability and importance of pain management in successful cancer survivorship.

The issues of pain management in these patients are often very similar to those of any chronic nonmalignant pain patient, although there are some exceptions. The potential for disease recurrence is always possible. Any new pain may imply the possibility of either a new disease process or recurrence, thus making patient interpretation of painful symptoms more difficult. Some studies suggest that fear of recurrence is negatively correlated with QoL.

5 Successful pain management for cancer survivors begins with detailed assessment, includes good health care team communication, the initiation of appropriate interventions, and ongoing reassessment of any interventions.

The natural history of chronic pain in cancer patients differs in that the initial pain complaint is often of significant intensity during the initial treatment phase, followed by chronic, less intense pain during remission.

6 Thus, cancer patients often start on opioid therapy during curative treatment and then develop chronic pain. Opioid treatment may often be continued without recognition of its potential hazards in a patient who no longer has pain from cancer. There may not be an obvious point at which the necessity for continued opioid therapy has been questioned. Uncontrolled and frequently escalating opioid therapy may not be the optimal therapy for chronic pain conditions such as myofascial pain associated with deactivation, particularly if opioid use is the primary focus of care. Problematic opioid use may be recognized in these circumstances by unchanged or decreasing functional status with escalating opioid use. Deciding when opioid therapy is more harmful than beneficial can be difficult. The prescribing clinician must determine if opioid treatment should be continued, stabilized, or discontinued. A tapering schedule is the wisest way to discontinue opioids.

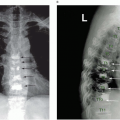

Long-term survivors may have other issues, which can include functional deficits, pain, fatigue, lymphedema, and altered bowel and bladder function. Simple activities such as mobility and the ability to perform self-care can be limited. In addition, reintegration into society with activities such as driving, social interaction, and return to work can be problematic. Cancer rehabilitation may improve QoL by minimizing disability and handicap caused by cancer and its treatment.

7Several different factors potentiate the risk for chronic comorbid conditions among cancer survivors. These include metabolic syndrome associated disease (obesity, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease), osteoporosis, and decreased functional status. Obesity is a well-established risk factor for cancers of the breast (postmenopausal), colon, kidney (renal cell), esophagus (adenocarcinoma), and endometrium; thus, a large proportion of cancer patients tend to be overweight or obese at the time of diagnosis.

8 Additional weight gain can also occur during and after cancer treatment in breast cancer, testicular, and gastrointestinal cancer patients. Because obesity is associated with cancer recurrence in both breast and prostate cancer, and reduced QoL among survivors, there is compelling evidence to support weight control efforts in this population.

9 Obesity is a common manifestation of several metabolic disorders that are frequently observed among cancer survivors. These disorders are grouped under the umbrella term, “the metabolic syndrome,” and also include diabetes and cardiovascular disease (CVD). Insulin resistance is the underlying event associated with the

metabolic syndrome and co-occurs with hyperinsulinemia and/or diabetes.

10 CVD is a major health issue among survivors, evidenced by mortality data which show that half of noncancer-related deaths are attributed to CVD.

11 Risk is especially high among men with prostate cancer who receive hormone ablation therapy, as well as patients who receive adriamycin, and radiation therapy to fields surrounding the heart.

12 Clinical studies suggest that osteoporosis remains an important health concern among survivors.

13 Functional status is often lowest immediately after treatment and tends to improve over time; however, the presence of pain and co-occurring diseases may affect this relationship.

14 Cancer survivors demonstrate almost a twofold increase in having at least one functional limitation, and, in the presence of another comorbid condition, the odds ratio increases to 5.06 (95% confidence interval [CI]: 4.47-5.72).

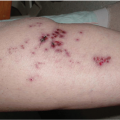

15Possible late effects of cancer and its treatment are listed in

Table 26.1.

The constantly evolving effect of a philosophical shift in cancer treatment from a primarily seek-and-destroy mindset toward one reflecting the importance of both curing the disease and controlling its attendant adverse sequelae significantly affects the cancer survivorship research paradigm. Cancer treatments today are increasingly used in the context of the survivor’s life, striving toward minimal toxicity yet optimal effectiveness and with recognition of the importance of interdisciplinary care and management. This philosophy must be communicated to researchers and care providers across diverse settings to promote its incorporation into the design of the next generation of cancer survivorship investigations. Aziz

16 summarizes the paradigm of cancer survivorship research as one that: