- Potential hazards facing the driver with diabetes include hypoglycemia, visual impairment, and disability from severe neuropathy or leg amputation.

- Hypoglycemia can severely disrupt driving skills by causing cognitive dysfunction and mood changes. Motor skills and judgment can become impaired when blood glucose falls below 3.8mmol/L, often without inducing hypoglycemic symptoms. Impaired awareness of hypoglycemia is a relative contraindication to driving. Drivers with diabetes must take precautions to avoid hypoglycemia and know how to treat it if it occurs while driving.

- Corrected visual acuity that is worse than 6/12 in the better eye precludes driving in the general population. People with diabetes may fulfill this criterion, but still have significant visual impairment (e.g. field loss, poor night vision and perception of movement) secondary to retinopathy, laser treatment or cataracts.

- In many countries, drivers with diabetes are legally required to declare the diagnosis for their driving license and motor insurance. Failure to do this will invalidate insurance claims.

- Driving licenses are often issued for fixed terms and only renewed following satisfactory medical review. In many countries, insulin-treated drivers are barred from driving passenger-carrying vehicles and large goods vehicles.

- Diabetes is not a bar to most occupations, and people with diabetes are protected in many countries by legislation against discrimination on the grounds of disability.

- People with insulin-treated diabetes are barred from certain occupations because of the risk of hypoglycemia. These include the armed forces, emergency services, commercial pilots, prison and security services, and jobs in potentially dangerous areas (e.g. at heights, underwater and offshore).

- Severe hypoglycemia in the workplace is uncommon and shift work seldom compromises glycemic control. Depressive illness and poor glycemic control are associated with higher unemployment and sickness absence in people with diabetes.

- Glycemic control may be suboptimal in prison because of restrictions in diet, exercise and blood glucose monitoring. Intercurrent illness and metabolic abnormalities may not be recognized or treated promptly.

- Input from a diabetes specialist may improve the quality of care. Knowledge of diabetes among prison officers and staff of short-term custodial units is often limited and may be improved by liaising with local diabetes specialist services.

- Diabetes should be declared to insurers, who may impose higher premiums or limited coverage. Many insurers’ decisions are based on outdated actuarial data or misconceptions about the current prognosis of diabetes. National diabetes organizations can provide details of insurance brokers who do not weight policies against people with diabetes.

- Life expectancy in type 1 diabetes can be modeled from age, sex and the presence of proliferative retinopathy and nephropathy. As the latter is a major determinant of survival, life insurance premiums should be reduced for all those who reach the age of 50 years without renal impairment.

- The association between excessive alcohol consumption, chronic pancreatitis and secondary diabetes is well established. Alcohol excess is also associated with central obesity and poor compliance with medication; both could increase the risk of type 2 diabetes and compromise control of established diabetes. Most epidemiologic studies, however, have demonstrated a U-shaped relationship between alcohol consumption and diabetes, with moderate intake being associated with a lower risk of diabetes.

- In type 2 diabetes, moderate alcohol consumption is associated with a 35% reduction in total mortality and lower risk of cardiovascular disease compared to abstinence. Excessive alcohol consumption is associated with hypertriglyceridemia and resistant hypertension; affected individuals have an increased vascular risk.

- Ethanol inhibits hepatic gluconeogenesis and increases the risk, severity and duration of hypoglycemia. Alcohol obscures the ability, both of the individual and of observers, to recognize and treat hypoglycemia, and intoxication can simulate hypoglycemia.

- Approximately one-third of young people with diabetes use recreational drugs at some time. The most common class of drug taken is cannabis, but amfetamine-type stimulants (including ‘ecstasy’), cocaine and opiates are also used.

- Recreational drug use is associated with a sixfold higher risk of death from acute metabolic complications of diabetes. Intravenous drug use is uncommon but is dangerous and is associated with omission of insulin therapy, frequent hospital admissions (usually with diabetic ketoacidosis) and high mortality.

- Cocaine and amfetamine-type stimulants can have profound hemodynamic effects through sympatho-adrenal activation. In addition to an increased risk of cardiac arrhythmias and myocardial ischemia, the sympathetic activation antagonizes the action of insulin and can precipitate diabetic ketoacidosis.

- Diabetes is not a bar to traveling, but changes in meals, physical activity and antidiabetic drug treatment en route and after arrival all need careful consideration. Important issues include travel insurance, medical identification, supplies and storage of medication and monitoring equipment and immunizations.

- During long flights, blood glucose should be monitored frequently and glycemic control relaxed to avoid hypoglycemia. Insulin injection schedules may require in-flight adjustment, especially if the time-shift exceeds 4 hours.

- In the Diabetes UK Cohort Study, “living alone” was associated with a more than fourfold increase in risk of death from acute metabolic complications of diabetes.

- Leaving home is potentially a period of high risk for young people with diabetes; particular concern has been expressed about the welfare of university students with type 1 diabetes.

Diabetes influences many aspects of daily life, principally through the effects of treatment and its potential side effects, particularly hypoglycemia. The development of diabetic complications, such as neuropathy and retinopathy, can also affect everyday activities, particularly when these are severe with clinical manifestations, or require time-consuming treatment such as dialysis for chronic renal failure.

Driving

Driving is an everyday activity that demands complex psychomotor skills, visuospatial coordination, vigilance and satisfactory judgment. Although motor accidents are common, medical disabilities are seldom responsible. Diabetes is designated a “prospective disability” for driving because of its potential to progress and cause complications, while side effects of treatment (principally hypoglycemia) can affect driving performance. In most countries, the duration of the license of a driver with diabetes is period-restricted by law, and its renewal is subject to review of medical fitness to drive. The problems associated with diabetes and driving and the limitations of relevant research data have been reviewed [1,2].

The main problems for the driver with diabetes are hypoglycemia and visual impairment resulting from cataract or retinopathy. Rarely, peripheral neuropathy, peripheral vascular disease and lower limb amputation can present mechanical difficulties with driving (Table 24.1), but these problems may be overcome by adapting the vehicle and using automatic transmission systems.

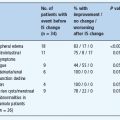

Table 24.1 Reasons for drivers with diabetes to cease driving.

| Newly diagnosed people with diabetes, especially insulin-treated, should not drive until glycemic control and vision are stable |

| Recurrent daytime hypoglycemia (particularly if severe) |

| Impaired awareness of hypoglycemia, if disabling |

| Reduced visual acuity in both eyes (worse than 6/12 on Snellen chart)–note use of mydriatics for eye examination will affect visual acuity |

| Severe sensorimotor peripheral neuropathy, especially with loss of proprioception |

| Severe peripheral vascular disease |

| Lower limb amputation |

Despite these challenges, drivers with diabetes do not appear to be involved in more accidents than their non-diabetic counterparts [3]. Population studies have shown no excess in accident rates among drivers with diabetes in Northern Ireland [4], Scotland [5], England [6], Germany [7], Iceland [8] or Pittsburgh in the USA [9], while a large survey of over 30000 drivers in Wisconsin, USA found only a modest increase [10]. In most surveys, however, incidents were self-reported and probably underestimated, while fatal accidents (in which a diabetes-related cause, such as hypoglycemia, could have had a role) were excluded. Accident rates may also have been lowered by regulatory authorities barring high-risk drivers and by drivers with advancing diabetic complications who voluntarily stop driving [4,5]. Practical advice for drivers with diabetes is given in Table 24.2.

Table 24.2 Advice for drivers with diabetes.

| Inform licensing authority* (statutory requirement) and motor insurer of diabetes and its treatment |

| Do not drive if eyesight deteriorates suddenly |

| Check blood glucose before driving (even on short journeys) and at intervals on longer journeys |

| Take frequent rests with snacks or meals; avoid alcohol |

| Keep a supply of fast-acting and longer-acting carbohydrate in the vehicle for emergency use |

| Carry personal identifi cation to indicate that you have diabetes (and are prone to hypoglycemia) |

| If hypoglycemia develops, stop driving, switch off engine, leave the driver’s seat and then treat |

| Do not resume driving for 45 minutes after blood glucose has returned to normal (delayed cognitive recovery) |

* In the UK, the licensing authority is the Driver and Vehicle Licensing Agency (DVLA), Swansea, SA99 1TU, UK.

Hypoglycemia

Drivers with insulin-treated diabetes often experience hypoglycemia while driving [4,5,11] and this can interfere with driving skills by causing cognitive dysfunction, even during relatively mild hypoglycemia that does not induce symptoms. Studies of subjects with type 1 diabetes (T1DM) using a driving simulator showed that driving performance often became impaired at blood glucose concentrations of 3.4-3.8 mmol/L, and deteriorated further at lower levels [12]. Problems included poor road positioning, driving too fast, inappropriate braking and causing “crashes” by stopping suddenly. Alarmingly, most did not experience hypoglycemic symptoms or doubt their competence to drive; only one-third treated the hypoglycemia, and only when blood glucose had fallen below 2.8 mmol/L [12]. In the UK, the Driver and Vehicle Licensing Agency (DVLA) does not distinguish between type of diabetes, and the restrictions are based on the use of insulin as therapy, as this can cause hypoglycemia in any person using this treatment. The risk of hypoglycemia in insulin-treated type 2 diabetes (T2DM) rises with duration of insulin therapy.

Judgement and insight become impaired during hypoglycemia, and some drivers with diabetes describe episodes of irrational and compulsive behavior while at the wheel [12]. Hypoglycemia also causes potentially dangerous mood changes, including irritability and anger [13]. In addition, asymptomatic hypoglycemia impairs visual information processing and contrast sensitivity, particularly in poor visibility [14,15], which may diminish driving performance.

Poor perception of hypoglycemia is also potentially dangerous. Many drivers with diabetes subjectively overestimate their current blood glucose level and feel competent to drive when they are actually hypoglycemic [16]. Impaired awareness of hypoglyc-emia, often associated with more frequent severe episodes, is particularly hazardous and is a common reason for revocation of the driving license. It is not an absolute contraindication to driving if it can be demonstrated, by frequent self-monitoring, that there is prolonged freedom from hypoglycemia [17].

Hypoglycemia is a recognized cause of road traffic accidents, but its true frequency and causal relationship to an accident are often difficult to ascertain. Blood glucose is seldom estimated immediately after a crash, and evidence for preceding hypoglyc-emia is often circumstantial. Hypoglycemia was the main cause of non-fatal motor accidents in the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial (DCCT); hypoglycemia was three times more common in the intensively treated patients, but the rate of major accidents was no higher, perhaps because of better precautionary advice [18]. Other studies found that the frequency of hypoglycemic episodes during driving correlates with the total number of accidents [4,5,19]. The frequency of hypoglycemia-related accidents is substantially lower than those caused by alcohol and drugs.

Avoiding and treating hypoglycemia while driving

General measures to avoid hypoglycemia are discussed in Chapter 33. All drivers with insulin-treated diabetes should keep some fast-acting carbohydrate in the vehicle: disturbingly, some do not [20,21]. Each car journey, no matter how short, should be planned in advance to anticipate possible risks for hypoglycemia, such as traffic delays. It is advisable to check blood glucose before and during long journeys, and to take frequent rest and meals. Unfortunately, this is seldom undertaken [22]. Driving expends energy and – as with other forms of exercise – prophylactic carbohydrate should be taken if the blood glucose is <5.0mmol/L [23].

If hypoglycemia occurs during driving, the car should be stopped in a safe place, and the engine switched off before consuming some glucose. In the UK, the patient should vacate the driver’s seat and remove the keys from the ignition, as a charge can be brought for driving while under the influence of a drug (insulin) even if the car is stationary. Driving should not be resumed for at least 45 minutes after blood glucose has returned to normal, because cognitive function is slow to recover after hypoglycemia [13].

Many features of hypoglycemia resemble alcohol intoxication, and semi-conscious hypoglycemic diabetic drivers are sometimes arrested on the assumption that they are drunk. Drivers with insulin-treated diabetes should therefore carry a card or identity bracelet stating the diagnosis. Individuals with newly diagnosed insulin-treated diabetes may have to stop driving temporarily until their glycemic control is stable.

Sulfonylureas is the only group of oral antidiabetic drugs that may cause hypoglycemia while driving, and people treated with these agents should be informed of this possibility. While GLP-1 agonists alone are not associated with a risk of hypoglycemia, this may be a problem when used in combination with a sulfonylurea. Blood glucose testing in relation to driving is not a requisite for drivers with group 1 licenses (see below), but may be required for holders of group 2 licenses who are taking this treatment combination.

Visual impairment

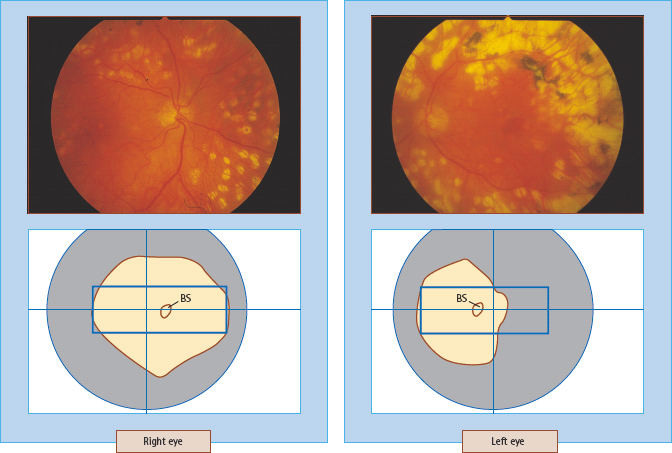

In the UK, monocular vision is accepted for driving, provided that the person meets the minimum legal requirement, i.e. is able to read a number plate with letters 8.9 cm (3.5 inches) high at a distance of 30 m (75 feet), wearing spectacles if necessary. This corresponds to a distance visual acuity of approximately 6/10 on the Snellen chart. The number plate test has deficiencies: it is poorly reproducible under clinical conditions and does not assess visual fields, night vision or the ability to see moving objects. All of these may be severely reduced by retinal ischemia in prepro-liferative retinopathy [24], while visual field loss can be caused by extensive laser photocoagulation for diabetic retinopathy [25,26] or macular edema (Figure 24.1) [27]; careful containment of laser burns may help to preserve vision [28]. Cataracts often accentuate glare from headlights, and in such cases driving in the dark should be avoided.

Figure 24.1 Visual field loss caused by photocoagulation. This 60-year-old man with diabetes needed heavy laser photocoagulation to the temporal retina of the left eye, causing nasal visual fi eld loss which caused this eye to fail the standard test for driving. The right eye required less intensive laser treatment and the visual fi eld was adequate for driving. BS, blind spot. Blue rectangle: minimum area recommended for safe driving. Courtesy of D. Flanagan, Addenbrooke’s Hospital, Cambridge, UK.

Previous surveys have identified very few drivers with diabetes who would fail the standard eyesight test. Impaired vision is an uncommon reason for the driving license to be refused or revoked [29], although many people stop driving voluntarily because their eyesight is deteriorating. Worsening vision from diabetic (or other) eye disease should be reported by the individual to the licensing authority.

Eye screening is a crucial part of assessing medical fitness to drive. Pupillary dilatation for fundoscopy or retinal photography temporarily reduces visual acuity, particularly if the usual binocular visual acuity is 6/9 or worse [30]. Patients should be told not to drive for at least 2 hours after the use of mydriatics. The driving regulatory authority may request perimetry to assess visual fields (Figure 24.1).

Statutory requirements for drivers with diabetes

In most developed countries, drivers with diabetes are required by law to declare their diabetes to the relevant regulatory authority (in the UK this is the DVLA). The statutory requirements for ordinary and vocational (professional) driving licenses vary considerably around the world; the national licensing authority should be contacted for details.

European driving licenses

Ordinary driving licenses (group 1)

The European Union (EU) States all use the same classification for driving licenses but this is not applicable to other areas. In the UK, the DVLA must be informed when a person with diabetes applies for a driving license, or if diabetes develops subsequently. Failure to do this constitutes “concealment of a material fact,” which can incur a fine [29], and can invalidate a claim to the motor insurers; professed ignorance of the law is not accepted as an excuse. The onus to declare rests with the individual driver, and doctors who provide diabetic care, including general practitioners, have a responsibility to inform patients of this legal requirement, and should offer practical advice (Table 24.2). Drivers with diabetes who are treated with diet alone or with antidiabetic medications do not have to notify the DVLA unless they have visual impairment or other diabetes-related problems that could affect medical fitness to drive. In the UK, a driving license is usually issued for a maximum of 3 years, and is renewed after completion of a medical questionnaire. The DVLA request further medical reports in a few cases, and always when an applicant reports a medical problem that may seriously affect driving (e.g. recurrent hypoglycemia). GLP-1 agonists (given by injection) can be used without restriction, other than when used in combination with a sulfonylurea for drivers with group 2 (vocational) licenses, when this must be notified to the DVLA and requires assessment of medical fitness to drive.

Although the member states of the EU have an agreed policy on restrictions on driving licenses for people with insulin-treated diabetes, considerable variations in policy and practical application exist between countries with respect to the implementation of the recommended regulations and how these are reviewed.

Vocational driving licenses (group 2)

It is extremely difficult to estimate the risk and likely outcome of a motor accident. In the absence of scientific evidence, risk and hazard are gauged by the size of vehicle being driven, which is perhaps not unreasonable, given the potential consequences of a hypoglycemic person losing control of a vehicle weighing several tons.

Most European countries restrict vocational (group 2) driving licenses for people with insulin-treated diabetes. These include category C licenses for large goods vehicles (LGV; previously called heavy goods vehicles) weighing over 7500 kg, and category D licenses for passenger-carrying vehicles (PCV; previously called public service vehicles), or those with more than 17 seats (including the driver^). In 1991, the then European Community (now the European Union) extended group 2 licenses to include small lorries and vans weighing 3500–7500 kg (category C1) and minibuses with 9–16 seats (category D1). Although all EU member states agreed to this policy (2nd European Council Directive on Driving Licences, 91/439/EEC), and presumably enacted appropriate legislation, considerable variations exist in the interpretation and imposition of these restrictions, and in some countries the EU Directive is openly disregarded. A few countries, such as the UK, Sweden and Spain, have robust systems in place to review medical fitness to drive at regular intervals. In the UK, C1 (but not D1) licenses are issued to drivers with insulin-treated diabetes as “exceptional cases” provided specific medical criteria are satisfied. A recent EU directive on driving has recommended individual assessment of all insulin-treated drivers with diabetes who apply for a Group 2 license, so medical fitness criteria will be modified in 2010.

Oral antidiabetic medication is not a bar to vocational driving licenses in the UK. In practice, however, many public transport companies restrict the employment of drivers with T2DM who take sulfonylureas; metformin or exenatide treatment is not a contraindication, but medical assessment is usually necessary. Progression to insulin therapy will terminate the employment of bus and train drivers. Taxi and ambulance drivers are not covered by the statutory regulations. In the UK, taxi licenses are issued by local authorities, which vary considerably in the assessment of medical fitness to drive [32,33], although many have now adopted group 2 licensing standards.

The European approach to vocational licensing has been criticized as being draconian and discriminatory against drivers with diabetes, showing how difficult it can be to balance the civil rights of the person with diabetes against the need to safeguard public safety.

Driving o utside Europe

Outside Europe, the regulations in different countries range from a complete ban to no restriction other than a medical examination for prospective or current drivers who require insulin [31]. Differences in approach between countries are influenced by the level of economic development and the prevalence of insulin-treated diabetes; many low and middle income countries impose no restriction on vocational driving licenses for people with insulin-treated diabetes [31]. In the USA, the Federal Highways Administration (FHWA) prohibits drivers with insulin-treated diabetes from driving commercial motor vehicles across state borders [35]. Within most states, drivers with insulin-treated diabetes can drive commercial vehicles except for lorries transporting hazardous materials and passenger-carrying buses.

In most other countries, insulin treatment alone is targeted by legislation, even though hypoglycemia can occur with other diabetic drugs. Interestingly, a Canadian survey of crashes involving truck and commercial vehicle drivers with diabetes revealed an increased in risk for drivers with T2DM treated with sulfonylu-reas [34], the presumption being that unsuspected hypoglycemia is a causal factor.

Aircraft pilot licenses

The UK Civil Aviation Authority does not allow individuals with diabetes treated with insulin or sulfonylureas to fly commercial aircraft or to work as air traffic controllers. Private pilot licenses can be issued to individuals with diabetes taking sulfonylureas (provided that they have a safety license endorsement), but not insulin. The EU has discussed introducing common airworthiness regulations for pilots with medical disorders.

Employment

With a few provisos, people with diabetes can successfully undertake a wide range of employment. There remains some prejudice against people with diabetes, but employment prospects in the UK and many other countries have improved with the introduction of legislation that makes it unlawful to treat a disabled person less favorably.

The main concern when considering people with diabetes for employment is the risk to safety associated with the condition or its treatment. Employers often fail to make the crucial distinction between a “hazard” (something with the potential to cause harm) and a “risk” (the likelihood that such harm will occur). The potential problems of diabetes relevant to employment are the hazards of acute hypoglycemia related to insulin and sulfonylureas, poor control of diabetes and the development of serious diabetic complications that may affect ability to work or interfere with performance at work.

Employment is generally restricted where hypoglycemia could be hazardous to the worker with diabetes, their colleagues or the general public. Employment-related issues, however, are not confined to people with T1DM. The rising prevalence of T2DM in the population of working age, along with the increasing use of insulin, has become an issue for occupational health assessment. Access to employment may be limited through discriminatory employment practices and restrictions posed by companies (rather than by legislation) because of perceived problems associated with diabetes or to job-sensitive issues related to the potential risks of hypoglycemia or to visual impairment. Diabetes can also affect employment through increased sick leave and absenteeism and by adversely influencing productivity. Diabetes in general has a negative long-term influence on the economic productivity of the individual; health-related disabilities can cause work limitations, especially in older employees in whom early retirement is more common on medical grounds.

A prospective survey in Edinburgh of 243 people with insulin-treated diabetes in full-time employment found that hypoglycemia occurred uncommonly at work (14% of all severe episodes) and had few adverse effects [36]. The study cohort, however, may have been subject to selection bias in terms of occupational diversity and many had suboptimal glycemic control; surprisingly few participants had impaired awareness of hypoglycemia. For some occupations (e.g. commercial airline pilots or train drivers) any risk of hypoglycemia is obviously unacceptable. Elsewhere, the case for employment restrictions may be less clear-cut.

Jobs that restrict the employment of workers with insulin-treated diabetes are listed in Table 24.3. People treated with insulin are not usually permitted to work alone in isolated or dangerous areas, or at unprotected heights. Shift-work is not necessarily a contraindication: one study in a car assembly plant found no difference in glycemic control between day and night-shift workers with diabetes, although control deteriorated if shift rotas were changed frequently [37].

Table 24.3 Forms of employment from which insulin – treated people with diabetes are generally excluded in the UK . Data from Waclawski [38] and Waclawski & Gill [56].

| Vocational driving |

| Large goods vehicles (LGV) |

| Passenger-carrying vehicles (PCV) |

| Locomotives and underground trains |

| Professional drivers (chauffeurs) |

| Taxi drivers (variable; depends on local authority) |

| Civil aviation |

| Commercial pilots and fl ight engineers |

| Aircrew |

| Air-traffic controllers |

| National and emergency services |

| Armed forces (army, navy, air force) |

| Police force |

| Fire brigade or rescue services |

| Merchant navy |

| Prison and security services |

| Dangerous areas for work |

| Offshore: oil-rigs, gas platforms |

| Moving machinery |

| Incinerators and hot-metal areas |

| Work on railway tracks |

| Coal mining |

| Heights: overhead lines, cranes, scaffolding |

In one British survey, the prevalence of diabetes in the workforce was 7.5 per 1000, including a lower-than-anticipated rate of 2.6 per 1000 for people treated with insulin [38]. Employment is generally disbarred in the armed forces, emergency work such as fire-fighting, civil aviation, jobs in the off-shore oil industry and in many forms of commercial driving [38]. Workers with diabetes seldom conceal their medical condition from their employers, and any blanket policy that disbars workers with diabetes from a specific occupation may be inappropriate or even discriminatory. Individual assessment is crucial, as employment regulations may not differentiate between different types and treatments of diabetes. Some bureaucratic regulations have been successfully challenged on medical grounds: for example, active fire fighters in the UK and a US air traffic controller were reinstated following appeals against dismissal.

In some cases, entering or persevering with a specific occupation may not always be in the individual’s long-term interests (e.g. with the advance of disabling complications). This is clearly a difficult issue, which may require sympathetic medical counseling because of possible repercussions on the individual’s income, self-esteem, future quality of life and the financial support of dependants.

Unemployment, sickness and diabetes

According to a British survey, employers do not generally believe that diabetes per se limits employment prospects, because most workers with diabetes have few medical problems and can tackle a wide range of occupations [39]. Discrimination by employers, however, may affect hiring practices; a US study reported that job applicants who told prospective employers of their diabetes were more likely to be refused than their non-diabetic siblings or individuals who did not declare that they had diabetes [40].

Some British and Dutch surveys reported no apparent excess of unemployment among people with diabetes as compared with the general population [41–44], but other studies in the UK [45,46] found that relatively more people with diabetes were not earning because of inability to work, intercurrent illness, early retirement or by being housewives. Although in many cases there was no apparent reason why an individual with diabetes could not obtain employment [46], depressive illness is strongly associated with unemployment and difficulties with work performance [47]. Adolescents with diabetes appear more likely than their non-diabetic peers to lose jobs, or to fail to follow their desired occupation or cope with shift-work [48]t Reduced employment and income in workers with diabetes in North American have been related to disability, which was seven times more common than among a sibling control group, was mainly related to diabetic complications [49,50] and was associated with lower employment income [51,52]. Sickness absence rates among employees with diabetes are reportedly either similar to, or 1.5- to twofold higher than in non-diabetic workers [40,53-55]. Workers with insulin-treated diabetes and good glycemic control had fewer sickness absences than those with poor control [56]; poor control itself (86 mmol/mol [HbA1c >10%]) is associated with a high rate of sickness absence [57].

Prison and custody

Imprisonment and short-term custody are unusual but troublesome life situations that can interfere with the management of diabetes. Hypoglycemia can occur if food is withheld after arrest, and may be confused with intoxication by alcohol or drugs. Diabetes is generally managed badly in prison because of the unsuitability of prison diets, lack of exercise and the practical difficulty of using some insulin regimens (e.g. basal bolus); also, self-monitoring may be prohibited, and glucose to treat hypoglycemia may be unavailable during long “l ock-up” periods. Most prison medical personnel have no specialist knowledge of diabetes and there may be no access to specialist supervision during custody.

Some prisoners with diabetes deliberately manipulate their treatment (e.g. by omitting insulin to induce ketoacidosis to have themselves removed to hospital which arguably offers a more amenable environment [59]). By contrast, treatment of intercur-rent illness may be delayed by prison staff, who think that the prisoner is “misbehaving.”

In some cases, withdrawal of alcohol, better dietary compliance and weight loss may actually improve glycemic control while in prison, and structured diabetic care can be provided effectively by an attending specialist physician [60,61]. Facilities for people with diabetes in police custody are generally limited, with an inability to measure blood glucose, treat diabetic emergencies or to provide insulin and appropriate meals [62]. A Scottish liaison initiative between a specialist diabetes department and the local police force identified and successfully addressed deficiencies in their custody facilities, including the provision of glucose monitoring equipment and the training of police staff [62]; this has been assisted by the development of a forensic nursing service.

Insurance

In many societies, insurance is viewed as essential to protect individuals and their families from the financial risk of unexpected events or illness, and insurance is often necessary to secure a financial loan, as for house purchase. People with diabetes are sometimes refused insurance or have to accept higher premiums and limited coverage, because the disorder is associated with reduced life expectancy, the risk of complications and greater use of health care services. Several factors are important for insurance underwriting, including the severity and duration of the diabetes, the extent of diabetic complications and other concurrent medical disorders. It is reasonable for an insurer to be cautious in dealing with applicants who have poorly controlled long-standing diabetes and established complications.

There is wide variation in insurance terms and premiums among different European countries [63], in the USA [64] and even within the UK [65], which suggests that insurers work from assumptions about diabetes rather than using scientific evidence from actuarial studies. The presence of T1DM may be the only factor considered by insurers [64], and many still base potentially discriminatory decisions on outdated information that reflects the poor outcome of diabetes diagnosed and treated decades ago. There are no standardized guidelines, nor is there any uniformity in the approach to diabetes and insurance [65], although risk classifications for life insurance have been published [66]. Some companies do not accept applicants with diabetes, while others do so without financial penalty. People with diabetes seeking insurance cover should therefore request quotations from several companies, and should be supported by a medical assessment from a physician who is competent in the specialty. Many national patient organizations have negotiated favorable terms with insurance brokers and will provide details on request.

The prognosis of people with diabetes (particularly T1DM) has improved considerably during the last 50 years, and the impact of this on life insurance for people with T1DM has been analyzed in Scandinavia [67]. In the last 30–40 years, median life expectancy has increased by over 15 years, largely because of substantial reductions in diabetic nephropathy. It has therefore been suggested that life insurance in T1DM should focus entirely on the risk of developing diabetic nephropathy [68], and a model to calculate insurance terms has been proposed, based on current age, age at diagnosis, sex, presence of nephropathy or proliferative retinopathy and other pre-existing disease [67] As the risk of nephropathy falls after 25 years of diabetes, all people who reach the age of 50 without nephropathy should have their insurance premium reduced. This approach has been adopted by most insurance companies in the Nordic countries, and by some in other European countries. To avoid penalizing people with dia betes, there must be regular updating of mortality and life expectancy data, and this information must be transmitted to actuarial advisers and insurance underwriters.

People with diabetes also face higher premiums for accident insurance, which is unjustified because there is no evidence that they have more accidents or permanent disability than the general population [69]. Neither is there any rationale for higher motor insurance premiums [64,65,70], particularly for those not treated with insulin, because no excess in road traffic accidents has been demonstrated (see above). A US study of the insurance cost of employees with diabetes showed that while health care expenditure was three times higher than all health care consumers, it was not more expensive than other chronic illnesses such as heart disease, asthma and cancer [71].

Diabetes must always be disclosed to the insurer: concealing the diagnosis constitutes the withholding of a material fact, which nullifies the contract with the insurer and thus the insurer’s liability in the event of a claim.

Alcohol

Many people enjoy drinking alcohol and diabetes should not be a barrier to social drinking. Accumulating data suggest that moderate alcohol consumption not only reduces the risks of developing T2DM but improves metabolic control and restricts diabetic complications. By contrast, alcohol can promote hypoglycemia and chronic excessive consumption may be deleterious both to long-term diabetes management and general health.

Alcohol consumption and risk of diabetes

Chronic high consumption of alcohol can predispose to the development of secondary diabetes. Alcohol has a direct toxic effect on the pancreas resulting in both acute and chronic pancreatitis. Diabetes complicates about 45% of cases of chronic pancreatitis (see Chapter 18). Insulin treatment is usually required to control hyperglycemia in patients with chronic pancreatitis, although diabetic ketoacidosis is rare. This may be because the pancreatic damage also destroys the α-cells that secrete glucagon, which is an essential factor in ketogenesis (see Chapters 13 and 34). A heavy alcoholic binge, with concomitant low food intake, can result in alcoholic ketoacidosis.

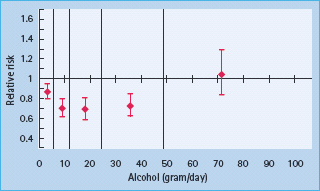

By contrast, modest alcohol consumption appears to protect against T2DM, reducing risk by up to 30% [72,73]. A U-shaped relationship has been observed between alcohol consumption and risk of diabetes, such that heavier drinkers and those who abstain from alcohol share a similar risk of developing T2DM (Figure 24.2). In epidemiologic and clamp studies, moderate alcohol consumption is associated with enhanced insulin sensitivity, which in part may be a consequence of reduced central adiposity [74]. Such epidemiologic data, however, may not provide an accurate assessment of risk for very heavy drinkers who tend to be underrepresented in such studies.

Figure 24.2 Pooled relative risk estimates for development of type 2 diabetes (with 95% confi dence intervals) for fi ve alcohol consumption categories (demarcated by the vertical lines) from 15 prospective studies. The categories are: ≤6 g/day; 6–12 g/day; 12–24 g/day; 24–48 g/day and ≥48 g/day. Reproduced from Koppes et al. [73], with permission from American Diabetes Association.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree