Several studies have demonstrated a dramatic increase in the number of skin cancer diagnoses in recent years.1,2 These increasing numbers amount to a growing patient population in need of skin malignancy management and subsequent reconstruction. Oncological surgeons should be equipped to manage these malignancies in all regions of the body. Following resection, patients are left with defects of variable sizes that involve a variety of cosmetically and functionally sensitive areas. This chapter gives oncological surgeons an outline of reconstructive principles when addressing such defects. For defects requiring more advanced reconstruction, such as the use of complex flaps, management generally would require the scope of practice of a reconstructive plastic surgeon.

There are three basic ways in which wounds heal. Primary healing occurs when wound edges are directly reapproximated, as in suturing two wound edges together. The healing process begins within hours after closure. Secondary wound healing, or “healing by secondary intention,” occurs when wounds are allowed to heal by contraction and epithelialization. Delayed primary healing occurs when a subacute or chronic wound is converted to an acute wound by sharp debridement and is then closed primarily.3

There are many factors that can complicate wound healing and these can create difficulties in reconstruction after resection of skin malignancies. Complications are more likely to occur when reconstructing tissue with a history of radiation therapy or infection, as well as in patients who have systemic illnesses, such as diabetes. Immunocompromised patients also exhibit delayed wound healing. Smoking and nutritional deficiencies can also negatively impact wound healing. When dealing with lesions in patients who have several factors decreasing their ability to heal wounds, it is important to first maximize their wound healing ability prior to reconstruction and to inform them that they are at a higher risk for postoperative complications.3,4

When attempting to close soft tissue defects, it is generally best to begin with the most straightforward reconstructive option. Healing by secondary intention or direct closure with primary healing is considered the most basic form of healing wounds. However, when this is not possible, other forms of reconstruction must be considered. Skin grafts can be appropriate coverage for some defects, but others will require more advanced soft tissue coverage with regional or distant flaps.4,5

When managing skin malignancies, reconstruction is often delayed while pathological results can be obtained. Temporizing dressings that can keep the wound clean and protected during the interim are useful. There are several dressings that can serve this purpose. In general, dressings that prevent skin retraction and prevent widening of the defect are most useful. Wound vacuum-assisted therapy can be useful in preventing wound edge retraction while also providing an occlusive dressing that removes fluid from the wound bed. This also typically requires less frequent dressing changes than traditional dressings and has been shown to decrease the size of some wounds. A wound bolster can also serve as a dressing. These are typically fashioned using Vaseline gauze covered by a plain gauze bolster over a wound that is secured with circumferential sutures. The most effective dressings tend to be those that protect the wound while minimizing discomfort to the patient. Skin grafts are sometimes used as temporizing dressings when awaiting pathology results or when further treatments, such as radiation, delay final reconstruction.3,4

See Chapter 159, “Principles of Skin Grafts and Flaps,” for information on this topic.

For soft tissue defects in certain regions without enough skin laxity to close the wound primarily, tissue expansion can be used to increase the amount of skin available for closure. Tissue expanders are most commonly used in the scalp and trunk, such as in delayed breast reconstruction.6 Approximately 50% of the scalp can be reconstructed with hair-bearing skin via expansion.7 Expanders are less frequently used in the extremities, as extremity tissue expansion has been associated with a higher complication rate.8,9

There are many wound care products on the market that serve as skin substitutes. These substitutes are often used as temporary dressings for wounds awaiting final reconstruction. Options include allografts, such as cadaveric skin or dermis, xenograft, which is tissue from a different species, or synthetic products, such as Integra10 (see Chapter 160 on “Dermal Substitutes in Oncologic Surgery”).

For defects that cannot be closed primarily and are not candidates for skin grafting, tissue must be brought in from elsewhere. Please refer to Chapter 159, “Principles of Skin Grafts and Flaps.” When dealing with soft tissue defects that need flap closure, it is often necessary to involve a reconstructive surgeon for assistance.

It is important to know the layers of the scalp when attempting closure of scalp defects. The layers of the scalp can be remembered using the mnemonic SCALP: S (Skin), C (subCutaneous tissue), A (Aponeurotic layer), L (Loose areolar tissue), and P (Pericranium).11

Vessels, lymphatics, and nerves course through the subcutaneous tissue, just superficial to the aponeurotic layer. The aponeurotic layer is commonly known as the galea. It serves as the strength layer of the scalp and is continuous with the frontalis and occipitalis muscles. The loose areolar tissue is also known as subgaleal fascia or innominate fascia and allows for scalp mobility. The pericranium is tightly adherent to the skull.11

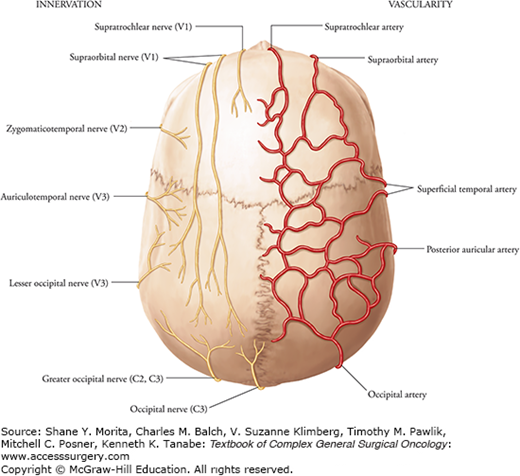

The blood supply of the scalp is derived from both the internal and external carotid systems and is divided into four distinct vascular territories. Five paired arteries supply these territories: the supraorbital, supratrochlear, superficial temporal, occipital, and posterior auricular arteries (Fig. 161-1). There is extensive collateralization among the four territories, which allows for successful scalp replantation based on a single vascular anastomosis.11

The supraorbital and supratrochlear arteries supply the anterior territory. The lateral territory is the largest of the vascular territories and is supplied by a terminal branch of the external carotid system, the superficial temporal artery. The occipital arteries supply the posterior territory. The posterolateral territory is the smallest and is supplied by the posterior auricular artery.11

Branches of the three divisions of the trigeminal nerve, the cervical spinal nerves, and branches from the cervical plexus supply sensory innervation to the scalp (Fig. 161-2).11

When possible, scalp defects should be replaced with scalp tissue. No other donor site in the body can mimic the hair-bearing quality of the scalp. Consider using tissue from the parietal region where scalp mobility is the greatest. Subgaleal undermining can increase mobility. The strong galea layer often limits scalp mobility. To increase tissue gain, the galea can be scored perpendicular to the direction of desired gain, taking extreme care to not injure scalp arteries that lie just superficial to the galea. When designing local flaps for coverage, at least one main, named scalp vessel should be incorporated to ensure adequate blood supply.12,13

If local tissue rearrangements are inadequate to cover scalp defects, tissue expansion can be useful and can often provide cosmetically superior results. Approximately 50% of the scalp can be reconstructed with tissue expansion before alopecia becomes a significant issue.7 However, expansion must be done in a staged fashion. In general, skin grafts should be used only as temporary closure when scalp reconstruction must be delayed.12,13

Available local tissue options in the scalp vary depending on size and location of the defect. This makes an algorithmic approach to closure useful.

Superficial temporal vessels supply the parietal scalp territory. The high scalp mobility in this region makes it particularly amendable to local tissue rearrangement for closure. Patients are also less likely to have exposed bone due to the underlying temporalis muscle. Reconstruction should avoid sideburn displacement when possible.

The posterior scalp is a region of moderate scalp mobility. Small defects will often close primarily, while moderate-sized areas often require rotation advancement flaps that include dissection over the trapezius and splenius capitis muscles to allow for adequate tissue gain. Larger defects will require extensive flaps.12,13

This area of the central scalp has very limited mobility, requiring extensive undermining and recruitment of tissue from more mobile regions. Small defects will often close after adequate subgaleal dissection. Medium and large defects will require rotation advancement flaps and often tissue expansion for appropriate reconstruction.12,13

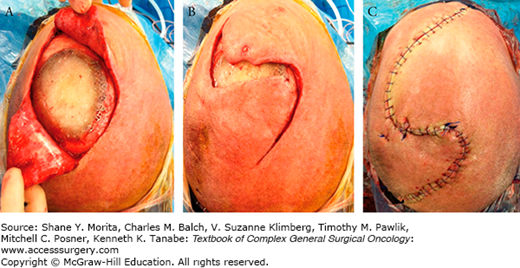

Rotation advancement flaps are commonly employed to close medium-sized defects of the scalp. At times, a unilateral advancement flap will close the wound, but often a second flap, creating bilateral advancement flaps, will be necessary for closure (Fig. 161-2). These flaps are elevated in the subgaleal plane. This plane typically dissects fairly easily with minimal bleeding. The area of tissue to be raised is fed by a pedicle, and this pedicle should include one of the above named vessels of the scalp. In general, the length of the pedicle to its base width should not exceed a 3:1 ratio to decrease the risk of necrosis. The tension at the closure site overlying the defect should be minimal. The advancement of the flap will create wound edges of uneven length, shortening the inner edge and lengthening the outer edge. This often results in a standing cone deformity. In scalp reconstruction, these should not be excised, as they will improve over time with healing. When possible, the galea should be closed, as this is the scalp strength layer and will provide a protective barrier. Absorbable sutures are typically used for galeal and subcutaneous/dermal closure followed by interrupted permanent sutures to reapproximate the skin edges. Techniques such as vertical/horizontal mattress sutures will assist in wound edge eversion. Prior to elevation of flaps, infiltration of a local anesthetic with dilute epinephrine will help decrease intraoperative skin edge bleeding and can be used to hydrodissect the subgaleal plane. The surgeon should minimize the use of hemostatic clips and electrocautery on the cut edges to prevent possible follicular damage. Remember that the galea can be scored perpendicular to the direction of desired tissue gain. This is often best performed with sharp dissection for precise incisions that avoid injury to the scalp arteries that run superficial to the galea.12,13

FIGURE 161-2

A. A scalp lesion has been resected that involved bone and required cranioplasty. Small anterior and posterior rotation advancement flaps have been created but (B) shows the flaps will not advance into the defect without undue tension. The anterior and posterior rotation advancement flaps are extended before closure (C), ensuring that at least one main vessel supplies each flap and that the incision will close without excess tension. (Used with permission from Dr. Barbu Gociman.)

The external ear is the site of 6% of all skin cancers and 10% of skin cancers in the head and neck.14 Squamous cell carcinomas are the most common with an average rate of cutaneous metastasis of 11% compared with 2% from other primary sites.15

The method of ear defect closure depends on defect thickness and location.

The ear is based on a cartilaginous framework. This framework lends itself to prominent anatomical landmarks. Knowledge of these landmarks is useful in discussing and planning excision and closure of ear lesions (Fig. 161-3).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree