Cancer of the skin is the most common human malignancy, and its incidence is rising worldwide. There are approximately 900,000 to 1,200,000 new cases of skin cancer annually in the United States, with melanoma representing about 59,940 cases and about 95% of deaths due to skin cancer ( ; Jemal et al., 2007). Although the majority of deaths due to cutaneous cancer are caused by malignant melanoma, nonmelanoma skin cancer is responsible for significant morbidity. Approximately 80% of nonmelanoma skin cancers are basal cell carcinomas, and 20% are squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs) ( ). SCC is the second most common cancer among whites. Unlike basal cell carcinomas, cutaneous SCCs are associated with a substantial risk of metastasis ( ). The major factors involved in the development of skin cancer today seem to be a combination of environmental ultraviolet (UV) light exposure and the ability to tan as controlled by genetic differences in skin color. These observations explain the high incidence of skin cancer in fair-skinned individuals and in those living in lower latitudes and higher altitudes. Dark skin is highly protective against the development of skin cancer. Exposure to ionizing radiation, either as part of therapy for a variety of benign disorders or as an occupational risk (e.g., dentists, radiologists), has also been implicated in the development of SCC. Arsenic, which is used in insecticides, has continued to be a significant cause of skin cancer in farmers and industrial workers. Finally, each of these causes may be enhanced by genetic defects in the body’s ability to repair DNA and by immunosuppression. Two disorders, xeroderma pigmentosum and basal cell nevus syndrome, are important, genetically transmitted conditions characterized by a much higher than average incidence of skin cancer. Human papillomavirus (HPV), especially in certain sites and in the setting of immunosuppression, has been shown to be implicated in the pathogenesis of SCCs.

Because skin cancer occurs on the body surface, careful inspection is the first step toward early diagnosis. Although each tumor described below demonstrates certain typical features that aid in the diagnosis, any lesion that shows biologic activity—as indicated by change in size, shape, or color—should be considered suspicious. Bleeding and ulceration are generally characteristics of more advanced lesions.

Benign Skin Tumors

Different forms of benign tumors may arise from the skin, reflecting the heterogeneity of resident cell types. It is important to identify these tumors so as to distinguish them from malignancies. Furthermore, it should be noted that many of these benign neoplasms are capable of causing functional disturbances, as well as cosmetic problems.

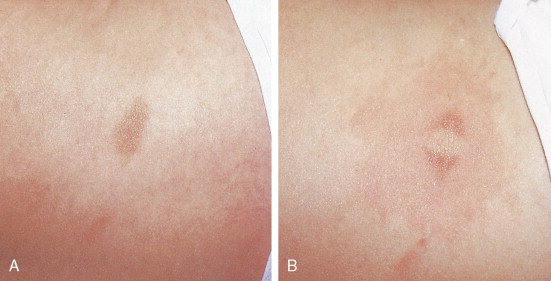

One of the most common benign tumors of the skin is seborrheic keratosis, which usually affect patients older than 30 years of age ( Figs. 13.1 and 13.2 ). Most people will develop at least one such lesion in their lifetime. Appendage tumors of the skin differentiate toward adnexal structures, including eccrine and apocrine sweat glands, hair follicles, and sebaceous glands. They may be solitary or multiple. Histopathologic examination is necessary for a correct diagnosis and classification of adnexal neoplasms ( Fig. 13.3 ). Other common benign tumors include those of vascular origin (hemangioma and variants), adipose tissue origin (lipoma and variants), fibrohistiocytic tumors (i.e., dermatofibroma), smooth muscle tumors, and neural tumors. Florid reparative processes such as hypertrophic scars and keloids may mimic true tumors ( Fig. 13.4 ). Mastocytosis (mast cell disease) can be classified in cutaneous and systemic variants ( ). Cutaneous mastocytosis includes mastocytoma ( Figs. 13.5 and 13.6 ), urticaria pigmentosa ( Fig. 13.7 ), and diffuse cutaneous mastocytosis. Cutaneous mastocytosis is frequently a benign condition and especially in children, tends to resolve spontaneously.

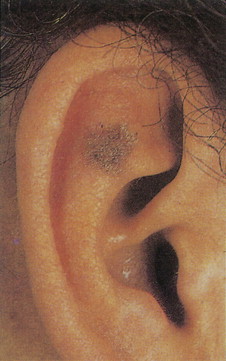

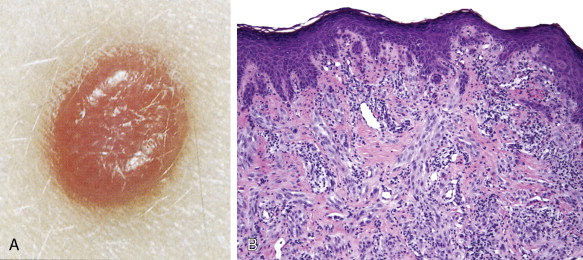

Among benign melanocytic neoplasias (nevi), Spitz nevus (spindle and epithelioid nevus) deserves special mention because of its unique characteristics ( Figs. 13.8 and 13.9 ) ( ) and the difficulty that it poses to clinicians and pathologists alike when it presents with atypical features. The original name of juvenile melanoma is confusing and should be avoided.

Premalignant Skin Tumors

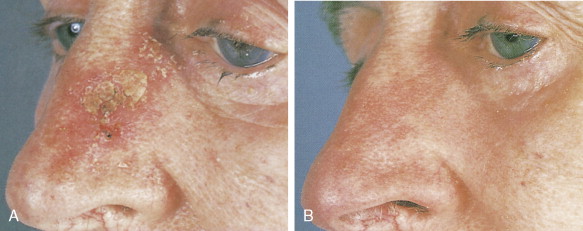

Actinic keratoses, also called solar keratoses, appear as thin, scaly, red lesions with epidermal hyperplasia and keratinocytic atypia ( Figs. 13.10 through 13.15 ). Although they are allegedly precursors of SCC, most do not proceed to frank malignancy, and conservative treatment is indicated. Because lesions tend to be multifocal and numerous, nonscarring methods of destruction, such as cryosurgery, electrodessication, or topical 5-fluorouracil cream, imiquimod 5% cream, and diclofenac 3% gel, are usually effective alternative therapies. Lesions that persist after treatment should be biopsied to rule out a malignant component. Topical sunscreens and other protective measures against sun exposure seem to be effective in preventing the development of new lesions.

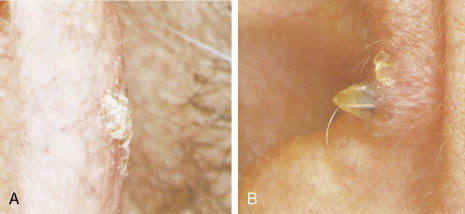

Arsenical keratoses are small, hard, punctate tumors that usually occur on the hands and feet ( Fig. 13.16 ). Increase in depth or diameter and ulceration of the lesions usually indicate progression to SCC.

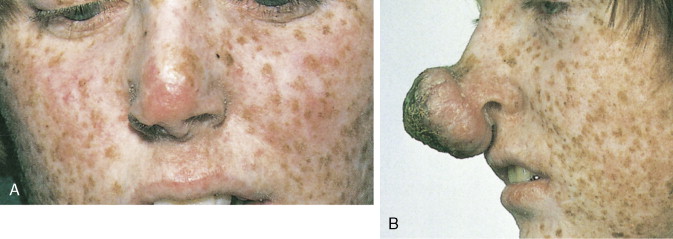

Xeroderma pigmentosum is an autosomal-recessive disorder characterized by the inability to repair UV light–induced DNA damage and, consequently, a pronounced cutaneous hypersensitivity to the effects of the sun’s rays. The disease, which starts in childhood, primarily affects the exposed parts of the body; lesions on the trunk may occur late in the course of the disease ( Figs. 13.17 and 13.18 ). Dryness, desquamation, and freckling are followed first by atrophic and telangiectatic spots, then by verrucous keratotic lesions. The most frequent malignancy is basal cell carcinoma, followed by SCC. Rarely, melanomas or sarcoma may also develop.

Patients with epidermodysplasia verruciformis, a generalized virally induced (HPV 5–associated) dermatosis, are also prone to develop SCCs.

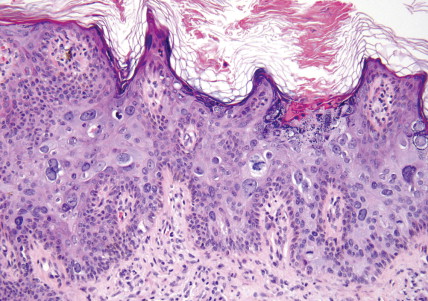

Bowen disease is a term used to describe a characteristic clinical lesion that presents as a well-demarcated, scaly, red plaque and that histologically corresponds to SCC in situ ( Figs. 13.19 through 13.22 ). Usually Bowen disease affects skin unexposed to sunlight. It should be emphasized that the diagnosis of Bowen disease is a clinicopathologic one. Lesions showing similar microscopic changes may not show the classical clinical features of Bowen disease. Some studies have shown an apparent increase in the incidence of visceral cancer in patients with Bowen disease, but others have failed to document such an association. Lesions of Bowen disease seem to be capable of developing into invasive SCC. Removal by simple excision is usually an adequate treatment.

Common Skin Cancers

BASAL CELL CARCINOMA

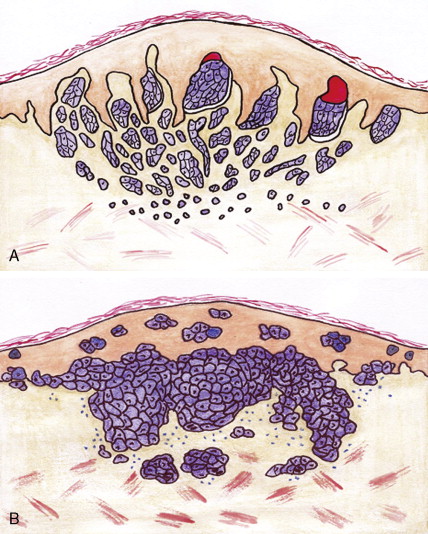

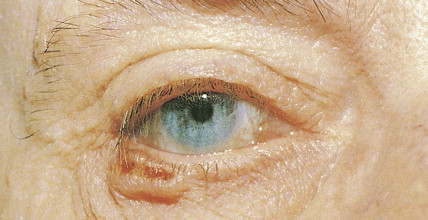

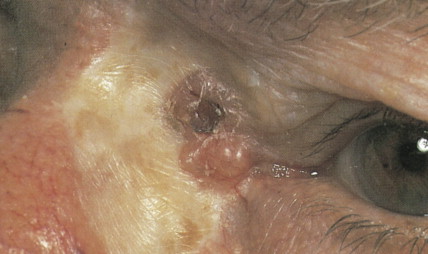

Basal cell carcinoma is the most common malignancy in white people, with an incidence that is increasing worldwide by up to 10% annually. Exposure to UV radiation is the main pathogenetic factor. The most classical clinical presentation is that of a pearly-gray papule or nodule with prominent telangiectasia ( Figs. 13.23 through 13.25 ). Histologically the lesions consist of small, undifferentiated basal cells with minimal nuclear atypia ( Fig. 13.26 ). Several clinical and pathologic variants exist, including nodular, micronodular, superficial, and infiltrative/morpheaform types ( Figs. 13.27 and 13.28 ). The majority of tumors are located on the face, neck, and dorsum of the hands. Superficial variants tend to be located on the trunk. Some basal cell carcinomas may be pigmented and can be clinically confused with melanocytic lesions, especially melanoma ( Figs. 13.29 and 13.30 ). Basal cell carcinomas can be locally destructive, but only exceptional reports of cases with metastatic behavior exist in the literature ( Figs. 13.31 through 13.34 ). The treatment of choice is surgery, but for superficial variants that tend to be broad and multifocal, cryotherapy, photodynamic therapy, and more recently topical treatment with immune response modifiers such as imiquimod have shown to be effective. Infiltrative variants with irregular borders and sometimes perineural invasion are more prone to recur, probably due to insufficient surgery. Recurrent tumors incur serious complications. Treating such lesions in a combined clinic, comprising a dermatologist, a plastic surgeon, and an oncologist, is recommended.

The basal cell nevus syndrome (Gorlin syndrome) refers to an autosomal-dominant disorder characterized by multiple basal cell carcinomas, associated with jaw cysts and skeletal anomalies ( Fig. 13.35 ). Patients have peculiar cutaneous pits in the palms and soles; the pits have histologic features of miniature basal cell carcinomas ( Fig. 13.36 ).

SQUAMOUS CELL CARCINOMA

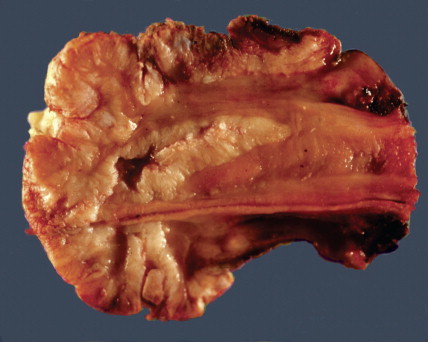

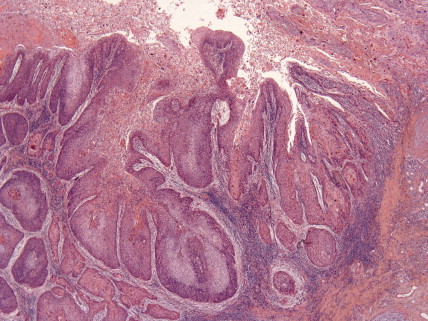

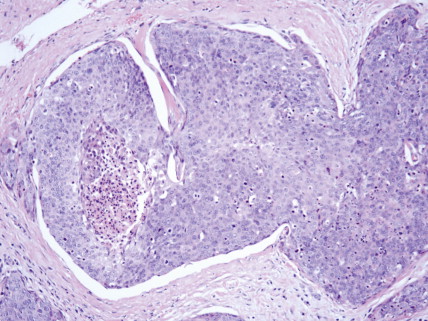

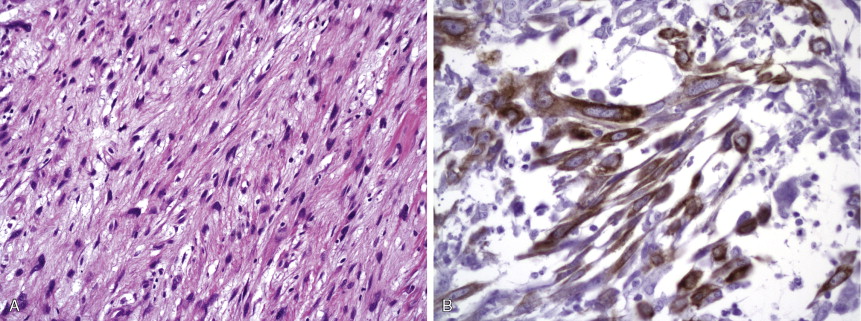

SCC is the second most frequent cutaneous malignancy (next to basal cell carcinoma) ( ). Tumors tend to occur in sun-exposed areas such as the face, neck, arms, and hands. The pathogenesis is multifactorial, with chronic actinic damage, particularly, in light-skinned patients, being the most important factor ( Figs. 13.37 through 13.40 ). One of the postulated pathogenetic mechanisms is the induction of TP53 mutations by UV light (Burnworth et al., 2006). Tumors affecting external genitalia and perianal and periungual regions seem to be HPV-associated in an important percentage of cases. The overall recurrence of SCC seems to be between 3.7% and 10%, and the metastatic rate 5.2% ( Fig. 13.41 ). However, when tumors are located in special sites such as the lip, ear, and anogenital areas, they show a higher rate of recurrence and metastasis. Tumors arising in the setting of inflammatory, scarring, and degenerative processes are also associated with a worse prognosis than those developing in sun-damaged skin ( Figs. 13.42 through 13.44 ). SCCs are usually classified based on a three-grade system as well-differentiated, moderately differentiated, and poorly differentiated tumors. Poorly differentiated tumors tend to have a more aggressive behavior. In addition to the usual classic type, several SCC variants that may show variable clinical behavior have been described ( ). Some of these variants include verrucous carcinoma ( Figs. 13.45 and 13.46 ), carcinoma cuniculatum ( Fig. 13.47 ) ( ), warty carcinoma ( Fig. 13.48 ), basaloid carcinoma ( Fig. 13.49 ), sarcomatoid carcinoma ( Fig. 13.50A, B ), adenoid (acantholytic) carcinoma, angiosarcomatoid (pseudovascular) carcinoma, clear cell carcinoma, mucoepidermoid (adenosquamous cell carcinoma), and lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma. Independently of the histologic variant and histologic grade and has been shown that depth of invasion and tumor thickness are the most helpful pathologic prognostic parameters ( ). SCCs less than 2 mm thick, which represent a high percentage of tumors, almost never metastasize. The risk of metastasis increases with tumors infiltrating the subcutaneous tissue. The risk of metastasis for undifferentiated carcinomas greater than 6 mm thick that have infiltrated the musculature, the perichondrium, or the periosteum, however, is quite high. Tumors between 2 and 6 mm thick with moderate differentiation and a depth of invasion that does not extend beyond the subcutis can be classified as low-risk carcinomas. In addition to high histologic grade, infiltration of subcutaneous tissue and deeper structures, and perineural and lymphovascular invasion are also indicators of poor prognosis.

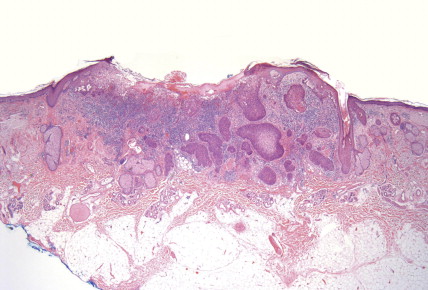

Transplant recipient patients who undergo long-term immunosuppression and patients with other forms of immune suppression are at increased risk for different neoplasms, and in the skin, especially SCC. These tumors tend to affect younger patients and are more frequently located in sun-exposed areas. The lesions tend to be clinically problematic, since they tend to be multiple and arise in a background of dysplastic epidermis ( Fig. 13.51 ). It appears that a good percentage of tumors in this setting may be HPV-related, and in fact it is not unusual to find features suggestive of a viral wart associated with frankly carcinomatous areas ( Fig. 13.52 ). It seems that tumors associated with immunosuppression tend to have a more aggressive behavior with a significant incidence of metastasis and even mortality ( Fig. 13.53 ) ( ).

KERATOACANTHOMA

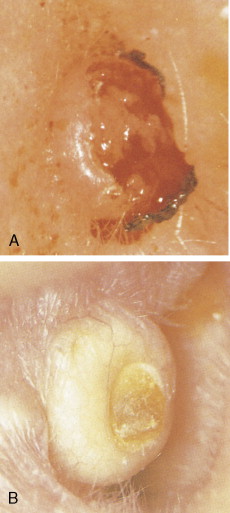

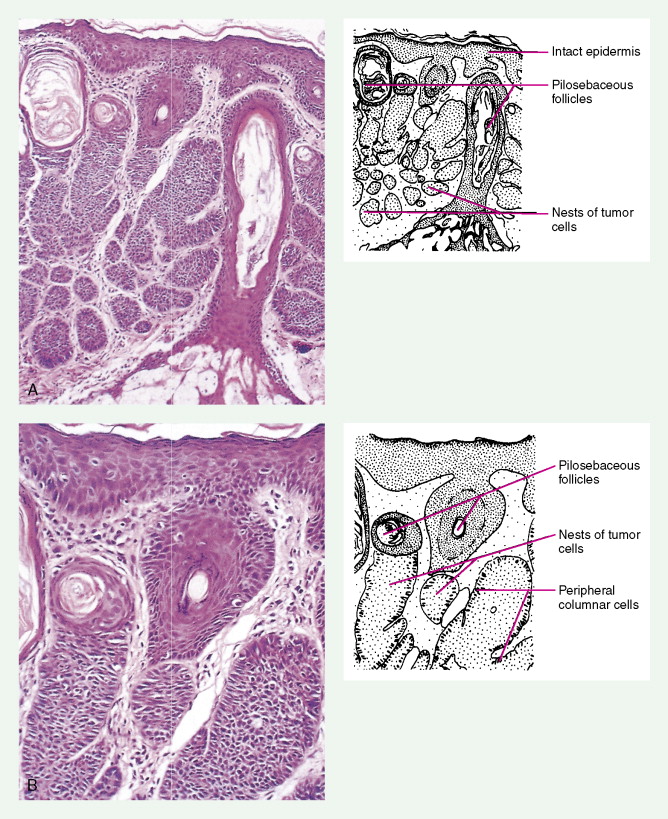

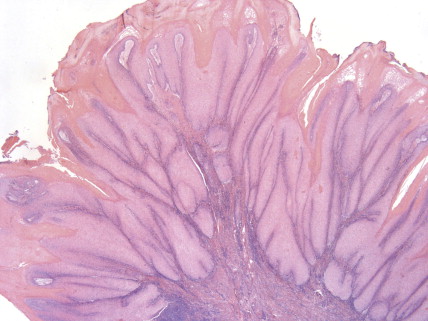

Keratoacanthoma is a rapidly growing tumor usually affecting sun-exposed skin of elderly patients. The classical presentation is that of a solitary discrete, round to oval, flesh-colored umbilicated nodule with a central keratin-filled crater ( Figs. 13.54 and 13.55 ). Lesions have a rapid clinical evolution and usually regress within 4–6 months ( Fig. 13.55 ). There has been a lot of controversy around this entity concerning whether it represents a benign or a malignant tumor, and multiple clinical and histologic criteria have been proposed to differentiate it from SCC ( Fig. 13.56 ). In unusual cases, however, lesions in the histologic spectrum of typical keratoacanthomas have been shown to follow an aggressive clinical course. Modern immunohistochemical and molecular techniques have not proved to be more useful in this distinction. With all of this controversy, and since there are no clinical or histologic criteria to classify a potential keratoacanthoma as a benign tumor that might spontaneously regress or as a neoplasm with metastatic potential, it seems most appropriate to consider keratoacanthoma as an extremely well-differentiated variant of SCC and to treat it as such ( ).