Skin

The purpose of this chapter is to discuss cutaneous carcinoma and melanoma. Uncommon cutaneous malignancies, such as angiosarcoma and dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans, will be addressed elsewhere. Most skin cancers are managed surgically. Because of the functional cosmetic deficits that may occur after surgery for skin cancers of the head and neck, the discussion will occasionally focus on lesions in this area.

Skin cancer is the most common of all malignancies. The American Cancer Society estimates that approximately two million basal cell carcinomas (BCCs) and squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs) are diagnosed annually in the United States, although the precise number is unknown because they are not reported.1 The risk for carcinoma of the skin increases with sun exposure. A low incidence occurs in dark-skinned people; a corresponding increase occurs in those with a fair, ruddy, Scotch-Irish complexion. The mortality rate is about 1,800 per year, or 0.45%.

Several conditions are associated with carcinoma of the skin, including the following:

• Actinic exposure

• Ionizing radiation

• Scar (e.g., burn scar)

• Chronic draining of sinus or fistulous tract (e.g., pilonidal sinus)

• Immune disorders

• Chronic lymphocytic leukemia

• Solid organ transplant patients

• Discoid lupus erythematosus

• Chemicals

• Arsenicals (herbicides, pesticides)

• Psoralens and ultraviolet light (PUVA) treatment for psoriasis54

• Nitrates

• Tars, oils, and paraffins

• Hereditary disorders

• Xeroderma pigmentosum

• Basal cell nevus syndrome

• Albinism

• Congenital epidermolysis bullosa

Melanoma is less common than BCCs and SCCs. Jemal et al.2 estimated that approximately 68,130 melanomas will be diagnosed in the United States in 2010 and that about 8,700 deaths owing to the disease will occur.

ANATOMY

ANATOMY

The epidermis is thinner in the face than in most portions of the body, measuring approximately 0.04 mm. No consistent change in the thickness of the epidermis occurs with increasing age, and no difference in skin thickness exists between men and women.

The dermis, which contains the blood and lymphatic vessels, adnexa, hair follicles, sweat glands, and sebaceous glands, is 1 to 2 mm thick; the dermis of the eyelid is thinner, ≤0.6 mm. Beneath the dermis lies the subcutaneous tissue containing the fat and the superficial fascia. No distinct transition occurs from the dermis to the subcutaneous layer.

Lymphatics

No lymphatics exist in the epidermis. A superficial capillary lymphatic plexus lies in the dermis and is without valves.3 The deep lymphatic trunks in the dermis and subcutaneous tissues have valves. The density of the capillary lymphatics has been noted to be about the same in all areas, except the sole of the foot and palm of the hand, where it is denser. Observation suggests that SCCs and melanomas occurring on the skin of the temple are particularly prone to develop lymphatic metastasis.4 During the healing of wounds, such as incisions or burns, a regeneration of lymphatic capillaries across the scar occurs, similar to the regrowth of small blood vessels.3

The first-echelon lymph nodes for carcinomas of the face and scalp are the superficial network of lymph nodes that form a ring around the top of the neck: submental (level IA), submandibular (level IB), parotid area, postauricular (mastoid), and occipital lymph nodes as well as inconstant facial lymph nodes.

PATHOLOGY

PATHOLOGY

The most common carcinomas of the skin are BCC (65%), SCC (30%), or one of their variants and the adnexal carcinomas. Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC) is a rare neuroendocrine malignancy arising in the skin that was first described by Toker5 in 1972. Verrucous carcinoma, a variant of SCC, occurs most often on the foot and is rare in the head and neck area. Carcinoma in situ (CIS) occurs frequently in the head and neck. Perineural invasion (PNI) is observed in 2% to 3% of patients with BCCs and SCCs.6

Noncutaneous carcinomas (e.g., renal cell carcinoma) may metastasize to the skin and subcutaneous tissues.

Basal Cell Carcinoma

The common BCC, which arises from the basal layer of the epithelium, may have a variety of growth patterns merge into one another in the same tumor, and the different names applied to the gross and microscopic appearances have clinical implications. The morphea type (sclerosing BCC) shows little surface disease and a marked infiltrating pattern; it is an important subtype because of the higher risk for recurrence. Microcystic BCC is a histologic variant of BCC that exhibits the same natural history as the more common variety. Some lesions will have mixed BCC and SCC (basosquamous cell carcinoma or metatypical BCC).

Melanin pigment may be seen on both gross and microscopic examination of BCC.

Squamous Cell Carcinoma

SCC and its variants (i.e., verrucous carcinoma, spindle cell SCC) are similar histologically to SCC occurring in other sites. Most are well differentiated. Evans and Smith7 identified two categories of spindle cell tumors of skin: one was composed of SCC mixed with a spindle cell component; the other was predominantly spindle cells. The spindle cell component is similar in both groups; mitoses, giant cells, and epithelioid cells may be seen.

Keratoacanthoma

Keratoacanthoma is a benign tumor of the skin that grossly resembles a cystic BCC and microscopically resembles SCC or squamous papilloma. Part of the difficulty in histologic diagnosis is owing to an inadequate biopsy specimen. Ackerman8 concluded that “the diagnosis of keratoacanthoma can only be made with absolute certainty by biologic behavior in the form of eventual involution.”

Adnexal Carcinoma

Carcinomas may arise from the epithelium of the sweat glands, sebaceous glands, or hair follicles and microscopically resemble the tissue of origin. Carcinoma of the sweat gland can arise from either the eccrine or apocrine glands; however, no reliable histologic criteria exist to differentiate the origin. It is difficult to distinguish between benign tumors and malignant carcinomas of the sweat gland in the absence of metastases. The differential diagnosis includes adenocarcinoma metastatic to skin and BCCs and SCCs with an adenoid cystic growth pattern. They are frequently misdiagnosed at the time of the first biopsy. Malignant trichilemmoma arising from hair follicles is extremely rare.

Microcystic adnexal carcinoma (sclerosing sweat duct carcinoma) is a rare variant of adnexal carcinoma first described in 1982. The lesion usually presents on the upper lip or skin of the periorbital area as an indurated plaque without direct invasion of the overlying epidermis. It tends to be slow growing and locally invasive.9–11 Microcystic adnexal carcinoma exhibits a propensity for local recurrence after excision and is associated with PNI; lymph node metastases are rare. The role of radiation therapy (RT) in the treatment of this rare malignancy is undefined.

Merkel Cell Carcinoma

MCC is a small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma arising in the skin. As in neuroendocrine carcinomas arising in other primary sites, MCC produces a neuron-specific enolase and has been found to contain membrane-bound neurosecretory granules within the tumor cell. In the past, the correct diagnosis often was not obtained until an extensive recurrence was noted. MCC was often misdiagnosed as BCC, lymphoma, adnexal carcinoma, or carcinoma metastatic to the skin from another primary site (i.e., small cell carcinoma of the lung or medullary carcinoma of the thyroid).12

Melanoma

Melanoma arises from melanocytes, which are present in the epidermis as well as in other parts of the body including the eye and respiratory, gastrointestinal, and genitourinary tracts.

PATTERNS OF SPREAD

PATTERNS OF SPREAD

The patterns of spread for individual anatomic sites are outlined in the Selection of Treatment Modality section. Some lesions remain confined to the epidermis (CIS) and may involve a large area of skin. Large in situ lesions occur more often on the trunk; however, small areas of CIS are common on the head and neck.

Basal Cell and Squamous Cell Carcinomas

Both BCC and SCC usually are well differentiated, and most have an indolent growth with distinct margins; a small proportion are poorly differentiated and grow rapidly. BCC occurs more frequently around the central portion of the face, whereas SCC occurs more often on the ears, preauricular and temporal area, scalp, and skin of the neck.

Most lesions remain superficial and invade the adjacent epidermis in a circumferential growth pattern. Invasion of the dermis usually is confined to the superficial (papillary) dermis. Eventually, penetration of the reticular dermis, subcutaneous tissues, and other underlying structures occurs. A few skin carcinomas tend to grow beneath the skin, and the surface lesion gives little indication of their extensive growth; this is more often seen in recurrent tumors. Most early BCCs and SCCs show an orderly invasion of the superficial dermis, which allows successful local therapy. Both BCCs and SCCs invade cartilage and bone, develop PNI spread, and eventually enter the lymphatics, although the latter is not common. BCC, in particular, has a low incidence of lymphatic involvement unless it is recurrent, whereas the incidence of lymph node spread for SCC is estimated to be 10% to 15%.

SCCs may develop distant metastases, whereas BCCs rarely produce metastases.

Metatypical BCC is intermediate between BCC and SCC as far as recurrence rates and the risk of metastases.13

Spindle cell tumors of the skin have a gross appearance and growth pattern similar to SCCs.

Carcinoma of the Sweat Gland

Carcinoma of the sweat gland occurs with equal frequency in males and females. It predominantly affects elderly people, although it may occur even in early adulthood. The lesion is generally a subcutaneous nodular mass, which may be solitary or multiple, and the larger lesions may be ulcerated. Carcinoma of the sweat gland most often occurs on the eyelid, face, and scalp. The growth rate varies from indolent to rapid. The tumor may be present for several years with little change and then suddenly begin to enlarge. PNI is frequent. Regional and distant metastases may develop. Scalp lesions are the ones most likely to develop metastases to regional lymph nodes.

Recurrence after excision is frequent, and often multiple recurrences are reported.14,15 Little information exists on the response to RT.15 In our limited experience, carcinoma of the sweat gland is sufficiently radioresponsive to justify RT, particularly in association with excision.

The mucin-producing sweat gland adenocarcinoma is a rare tumor. The eyelid is the primary site in about one-half of cases and the face and scalp in another one-fourth of cases. The tumor presents most often in middle-aged men. Wright and Font16 reported 21 cases that originated on the eyelid. Eight patients (38%) developed one or more local recurrences, one patient died with extensive persistent disease in the face after a 15-year interval, and only one patient had metastasis to the submandibular lymph nodes successfully treated by radical neck dissection.16 Regional or distant metastasis is a relatively infrequent event for lesions arising in the head and neck area.

Sebaceous Gland Carcinoma

Sebaceous gland carcinoma is rare. It occurs most often on the eyelids, predominantly on the upper lid in elderly women, although the lower lid and caruncle are also sites of origin; it may occur on other parts of the head and neck skin as well. It is often indolent in its growth; however, it may be locally aggressive and develop regional and distant metastases. Local recurrence is common after excision because the lesions often have significant deep and lateral spread beyond the obvious lesion. Metastasis to regional lymph nodes is reported in about 20% of cases, and a small percentage of patients develop distant metastases.17 Inadequate treatment often occurs because of incorrect histologic diagnosis.

Keratoacanthoma

Keratoacanthoma benign lesions start as a firm, round skin nodule and grow to 1 to 2 cm in a short time, usually a few weeks. As the lesion matures, the center becomes separate and can be removed, revealing a small crater. The lesion occurs most often in the exposed area of the head and neck. Keratoacanthoma is an unlikely diagnosis for a lesion of the lip vermillion. Typically, keratoacanthoma is twice as common in men as women. It occurs most often in patients older than 40 years of age, although it may be seen as early as the second decade of life.

Basal Cell Nevus Syndrome

The basal cell nevus syndrome is an autosomal-dominant disorder with a high level of penetrance but a variable clinical picture. The clinical syndrome may be composed of any or all of the following:

• Multiple BCCs (differing only in their tendency to develop at an early age and on unexposed skin areas)

• Jaw cysts (common)

• Palmar or plantar pits

• Skeletal abnormalities (short fingers, hypertelorism)

• Ectopic calcification

• Eye muscle palsies

• Hamartomas

• Epidermal cysts

The age at onset is frequently in the second or third decade of life, and a family history is often positive for the disorder.18

Merkel Cell Carcinoma

MCC occurs primarily in white men between 60 and 80 years of age.19 The lesion often presents as a painless, raised skin nodule or mass that is red, pink, or blue and may have diffuse margins, and is covered with an intact epidermis. Most lesions are ≤2 cm in size at diagnosis.19 Human polyomavirus is thought to be etiologic in a significant proportion of patients; human polyomavirus DNA in the MCC cells may be associated with an improved prognosis.19

MCC displays an aggressive growth pattern. Mojica et al.20 reported on 1,665 patients from the National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) database and observed the following extent of disease at diagnosis: localized, 55%; positive regional nodes, 31%; distant metastases, 6%; and no data, 8%.

Melanoma

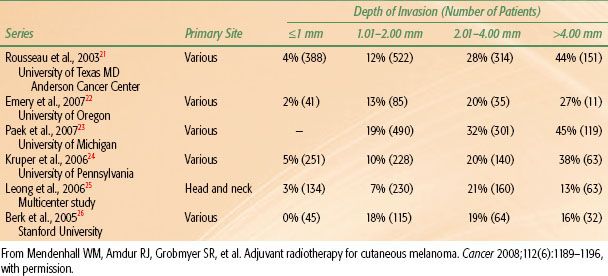

Melanoma is more aggressive and prone to metastasize to regional lymph nodes and exhibit hematogenous dissemination compared with BCC and SCC. The likelihood of regional and/or distant metastases is related to the depth of invasion of the primary tumor. The incidence of positive sentinel lymph node biopsies (SLNBs) versus depth of penetration is depicted in Table 33.1.

Lymphatics

The overall risk of lymphatic metastases is estimated to be 10% to 15% for cutaneous SCC of the skin. The risk increases with the size of the lesion, depth of the penetration, histologic grade, and recurrence.

The risk of lymph node metastases from previously untreated BCCs is <1% and is not related to size, depth of penetration, or histologic subtype; the risk increases for recurrent BCCs, especially those with multiple recurrences over several years. Lymph node metastases, however, are seen on rare occasions without a history of recurrence, and an interval of several years may occur between the treatment of the primary lesion and the appearance of involvement in lymph nodes. When they do occur, lymph node metastases often are solitary.

CLINICAL PICTURE

CLINICAL PICTURE

Presenting Symptoms

The common history for BCC or SCC is a slowly enlarging growth on or just beneath the skin surface. Often a history exists of a sore that will not completely heal. Other symptoms such as bleeding or pain are unusual until the lesion becomes large, and even then symptoms are relatively mild and infrequent. Patients with PNI may complain of paresthesia, especially the sensation of worms crawling under skin (formication). PNI is usually observed with midface lesions and most often involves cranial nerves V2 and/or VII.6 Advanced, neglected lesions with bone and cartilage destruction, orbit invasion, and regional metastases may be seen; these advanced lesions often produce few, if any, symptoms, and patients simply delay consulting a physician.

Melanomas usually present as a pigmented skin lesion associated with a change in color, shape, and/or size. Although most probably arise de novo, some may arise in a previously benign nevus. Occasionally, patients present with regional or distant metastases without an apparent primary tumor.

TABLE 33.1 PRIMARY DEPTH OF INVASION VERSUS SENTINEL LYMPH NODE BIOPSY POSITIVITY

Physical Examination

The site, size, and mobility of the primary lesion is documented. Depending on location, evidence of PNI is assessed as well as any findings that might suggest involvement of underlying bone on cartilage. The regional lymph nodes must be carefully examined, even though they are not often involved. Because of the infrequent appearance of regional lymphatic metastases, and because cases of skin cancer often are not followed diligently, lymph node metastases frequently are missed. Although lymphatic metastases may appear within a few months of the management of the primary lesion, in some cases many years intervene before the regional lymph nodes become apparent. It is not at all unusual for ≥5 years to intervene between the primary lesion and the appearance of metastases. Patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia and concomitant skin cancer often have enlarged lymph nodes from both processes and may have elements of SCC and leukemia in the same lymph nodes.

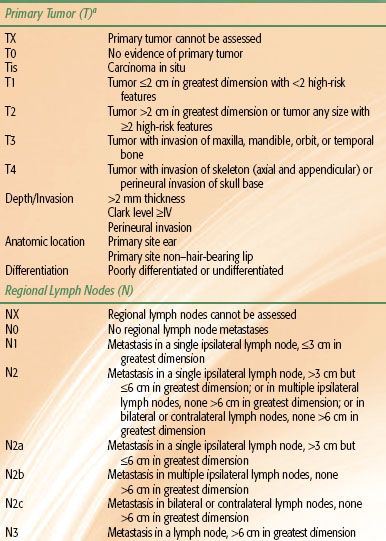

TABLE 33.2 2010 AJCC STAGING SYSTEM FOR BASAL CELL AND SQUAMOUS CELL CARCINOMAS

METHODS OF DIAGNOSIS AND STAGING

METHODS OF DIAGNOSIS AND STAGING

Biopsy should be performed on the majority of lesions before deciding on treatment. We do not always insist on biopsy for elderly patients who have a typical skin carcinoma and are to be treated by RT.

Small lesions occurring on the free skin areas (i.e., not involving the eyelid, ear, or periorbital areas) usually can undergo biopsy and be treated simultaneously with surgical excision. Larger lesions, or those involving areas where functional or cosmetic deficit might occur from excision, first undergo biopsy with a small excisional biopsy or with a skin punch. Biopsy with a skin punch should include the subcutaneous fat; punch biopsy is contraindicated when differentiating between keratoacanthoma and SCC because of the small sample size.

The following is a partial list of conditions to be considered in the differential diagnosis of BCC and SCC:

• Senile keratosis

• Keratoacanthoma

• Nonpigmented nevi

• Melanoma

• Cutaneous horn

• Psoriasis

• Lymphoma (mycosis fungoides)

• Soft tissue sarcomas (dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans)

• Hemangiosarcoma

• Metastatic carcinoma

• Adnexal carcinoma of skin

• MCC

Staging

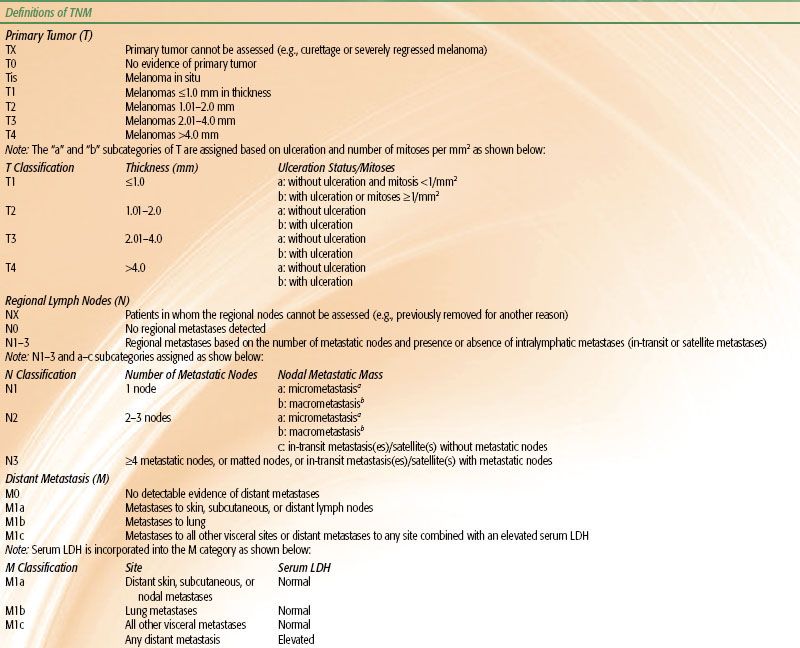

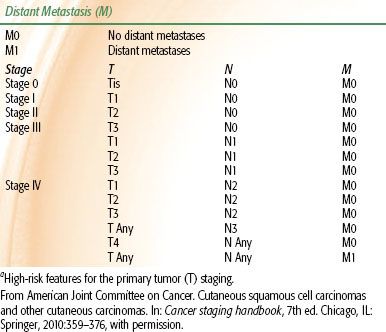

The 2010 American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) systems for BCC/SCC and melanoma are depicted in Tables 33.2 and 33.3, respectively. Although there is an AJCC staging system for MCC, we prefer the Yiengpruksawan system for this rare entity because of its simplicity: stage I, localized; stage II, regional lymph node metastases; and stage III, distant metastases.27

Diagnostic Imaging

Computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are only necessary in a carefully chosen group of patients being treated for skin cancer. CT is the primary modality for showing bone invasion and nodal metastases. High-resolution MRI is better than CT for demonstrating PNI.28 Positron emission tomography (PET) is useful to detect regional and distant metastases in patients with MCC and melanoma.

SELECTION OF TREATMENT MODALITY

SELECTION OF TREATMENT MODALITY

Basal Cell and Squamous Cell Carcinomas

The likelihood of cure is similar after surgery or RT for early-stage BCCs and SCCs.29 Therefore, selection of one modality over another is based on other parameters such as function, cosmesis, age of the patient, convenience, cost, availability of appropriate RT equipment, and the wishes of the patient. Patients with advanced cancers are often best treated with surgery and adjuvant RT if the cancer is resectable and the functional and cosmetic outcomes are acceptable.

Radiotherapy Alone

Small skin cancers located on “free skin,” such as the cheek or forehead, may be easily excised with a good cosmetic result and minimal inconvenience; therefore, surgery is usually the treatment of choice for such lesions. It is also desirable to avoid RT in young patients because the late effects of irradiation progress gradually with time and, with very long-term follow-up, may be associated with a suboptimal cosmetic result compared with resection and reconstruction. In contrast, resection of an early-stage skin cancer of the eyelid, external ear, or nose may result in a significant cosmetic deformity and necessitate complex reconstruction that compares unfavorably with RT. This is particularly relevant in the case of older patients who have a limited life expectancy and who are at higher risk for a perioperative complication.

Patients with locally advanced skin cancers present a difficult problem because, although the likelihood of cure may be better with combined RT and surgery in some situations, the cosmetic result is sometimes unacceptable. Patients receive postoperative RT if surgery is indicated and feasible. If surgery is not feasible, the patient is managed with RT alone. Although it might seem that the risk of bone and/or cartilage necrosis would be high after RT for a skin cancer invading these structures, the observed risk of complications is relatively low.30,31 Exceptions are advanced cancers of the scalp and those overlying the anterior aspect of the tibia where there is little tissue between the skin surface and the bone. Following definitive RT, bone exposure is likely and may progress to an osteoradionecrosis (ORN) requiring surgical intervention.

Patients with lesions associated with clinical PNI with gross tumor extending to sites that render complete resection unlikely or unfeasible, such as the cavernous sinus, are treated with RT alone. Subtotal resection does not enhance the likelihood of cure and only increases the morbidity of treatment.

TABLE 33.3 2010 AJCC STAGING SYSTEM FOR MELANOMA