Signs, Symptoms, and Paraneoplastic Syndromes

David S. Finley

Brian Shuch

Allan J. Pantuck

INTRODUCTION

Renal cell carcinoma (RCC) has justifiably acquired the moniker “the great mimicker” or “the internist’s tumor” because of its propensity to present with manifold clinical signs, symptoms, and paraneoplastic syndromes (PNS). Beyond the classic “triad,” (pain, abdominal mass, and hematuria), the clinical presentation of RCC can vary widely and depends on the degree of local tumor extent, the presence and particular sites of distant spread, and the systemic effects of the tumor. In recent years, incidental detection of RCC has become the most common mode of presentation due to increased use of abdominal imaging (1,2,3). Despite this shift in clinical presentation, clinicians must remain aware of the classic signs and symptoms of RCC. Incidental tumors, which by definition present without associated clinical signs, symptoms, or paraneoplastic findings, tend to be smaller in size, lower in grade, present at earlier stages, and are associated with a better prognosis than symptomatic tumors. On the other hand, the presence of individual signs or symptoms in symptomatic tumors may give ancillary, valuable, early clues regarding the size and spread of the tumor. In addition, these clinical manifestations may by themselves have prognostic significance and can portend an ominous prognosis when due to metastatic disease. Indeed, at the University of California, Los Angeles, we analyzed the presenting symptoms of patients with RCC and divided them into three groups: true incidental tumors, classic triad symptoms, and constitutional symptoms (weight loss, fever, night sweats, anorexia, cough, malaise, etc.), to determine the effect of presenting symptoms on patient survival. The median survival for patients with incidental, triad-associated, and constitutional symptom tumors was 117, 56, and 29 months, respectively (1). It is this differential impact on patient survival that has led to the incorporation of individual signs or symptoms, or even the inclusion of performance status scales such as the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) patient performance status (PS) scale into multivariable nomograms that can stratify seemingly similar patients into subgroups having divergent risk profiles [ULCA Integrated Staging System (UISS), Motzer etc.] (4,5). Performance status can be regarded as a convenient common denominator for the overall impact of multiple objective and subjective symptoms and signs on the welfare of patients.

RCC is further unique among genitourinary malignancies in that up to 20% of individuals will initially present with PNS, while up to 40% of patients may manifest them during their disease course (6). Although incompletely understood, most PNS appear to occur due to extratumoral release of biologically active proteins or through modulation of the immune system by immune complex production, immunosuppression, or induction of autoimmunity. Regardless of mechanism, the effects are systemic, occurring remotely from the tumor. PNS can occur across all histologic subtypes, in the setting of metastatic and nonmetastatic disease, and are not generally a result of local tumoral invasion. A hallmark feature of these syndromes is an improvement or resolution of symptomatology after removal of the tumor or reduction in tumor burden with systemic therapy.

LOCAL FINDINGS

Flank Pain/Abdominal Mass

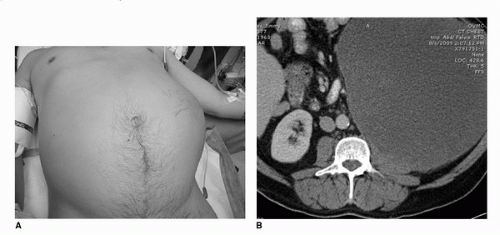

While once a telltale sign of RCC, abdominal masses are now seen infrequently. The classic triad of flank pain, abdominal mass, and hematuria, during modern series accounts for <5% of the patient population (7,8). Rare cases, however, do still present in this manner and can be quite impressive on clinical exam (Fig. 37.1A,B). Renal tumors will not generally present with a flank mass or pain until they reach an advanced state owing to their well-protected anatomic location in the retroperitoneum, insulated by perinephric fat and located behind the abdominal cavity and anterior to the thick paraspinal musculature of the back. Small tumors are therefore generally incidentally detected, while their larger counterparts can cause significant problems due to local extension by exerting local compressive effects on surrounding tissues. Occasionally, tumors can invade outside Gerota’s fascia into surrounding organs such as the adrenal gland, spleen, liver, pancreas, stomach, colon, and the psoas muscle. Resection of these locally invasive tumors will often improve symptoms and patient PS.

Patients with flank pain may be discovered to have a spontaneous renal hemorrhage of unknown etiology. Imaging may appear similar to those presenting with a perirenal hematoma secondary to renal trauma. In a large majority of cases, the hemorrhage is related to the presence of a renal tumor, either an angiomyolipoma or a RCC (7,8). With large renal masses, the etiology of the bleed is obvious; however, small tumors may be obscured by the perinephric hematoma. For these patients, a renal lesion may only be demonstrated once the hematoma resolves.

Large lower pole tumors or bulky lymphadenopathy may impair drainage of the collecting system. Significant ureteral obstruction will result in hydronephrosis and possibly flank pain. The presence of hydronephrosis with a renal mass should also prompt a thorough workup to rule out an upper tract transitional cell carcinoma. This finding would necessarily

alter surgical planning to include the need for ureterectomy and bladder cuff removal.

alter surgical planning to include the need for ureterectomy and bladder cuff removal.

Hematuria

Hematuria, gross or microscopic, is associated with renal tumors in approximately 35% of cases (2). Urine can range in color from a rusty brown to pink to bright or dark red with or without clots. All patients with hematuria should be advised to undergo a complete workup with upper tract imaging, urinary cytology, and cystourethroscopy. Depending on tumor location, small renal masses may or may not be responsible for the hematuria, and an incomplete workup that does not include cystoscopy may miss concomitant bladder pathology. Direct invasion into the collecting system is an obvious cause of hematuria, and therefore bleeding is more commonly observed with these tumors (56% with invasion vs. 33% without invasion) (9,10). Two large series demonstrated the incidence of collecting system invasion to be 14% (9,10). However, frequently hematuria can occur without gross collecting system invasion.

Venous Obstruction: Varicoceles, Lower Extremity Edema

Large inferior vena cava thrombi can cause complete obstruction of the venous return from the lower half of the body. Venous outflow obstruction frequently leads to a variety of symptoms that are determined by the degree of obstruction, rapidity of progression, and the presence or absence of collateral drainage. The rapid development of varicocele is considered a traditional sign of a potential tumor thrombus. The obstruction of drainage from the left and right gonadal veins due to the thrombus leads to the observed pathology. Left-sided varicoceles are more commonly observed in the setting of a benign etiology, while the presence of new onset, right-sided varicocele should raise greater suspicion. Bilateral lower extremity edema is common with an advanced tumor thrombus due to RCC.

SYSTEMIC FINDINGS: CONSTITUTIONAL SYMPTOMS AND METASTATIC PRESENTATIONS

Constitutional

Fevers and Night Sweats

The so-called “neoplastic fever” or paraneoplastic fever has been observed in association with a variety of cancers including RCC. Patients with RCC may complain of bothersome, intermittent fevers and/or night sweats. Actual fever associated with RCC is rare and is observed in fewer than 10% of patients (6,11,12). Fever and night sweats are found more frequently in those patients with metastatic disease and rarely in those with small, localized tumors. The etiology of associated tumor-related fever is unknown but is probably related to cytokine release. Many cytokines have been identified as mediators of fever (i.e., endogenous pyrogens) including IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α (13). Tumor-associated fever may respond to acetaminophen or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, particularly naproxen.

Weight Loss

Cachexia is a syndrome common in cancer patients that is associated with progressive atrophy of skeletal and adipose tissue with preservation of nonmuscle protein stores (14). This tissue wasting phenomenon may be associated with anorexia but is frequently not the primary cause of weight loss. Over the past few decades, there has been a better understanding of the complex mechanisms of tumor-related cachexia. Aggressive tumors have high metabolic demands and can increase the total energy requirements of the tumor-bearing host. Tumors frequently rely on energy inefficient glycolysis and therefore require high levels of glucose (15). The increased energy requirement can push the body to a state of catabolism. Another important finding in cancer associated-cachexia is alteration of adipose

tissue metabolism. Adipose tissue metabolism becomes deranged in malignancy leading to cellular atrophy (16,17). Various cytokines such as TNF- a, once known as cachectin, can activate lipolysis and deplete fat stores (18). Zinc-α2-glycoprotein (ZAG) is another molecule that has been implicated in the alteration of fat metabolism in cancer patients. ZAG, formerly known as lipid mobilizing factor, can be identified in the urine of cancer patients and has been found to strongly induce lipolysis (19).

tissue metabolism. Adipose tissue metabolism becomes deranged in malignancy leading to cellular atrophy (16,17). Various cytokines such as TNF- a, once known as cachectin, can activate lipolysis and deplete fat stores (18). Zinc-α2-glycoprotein (ZAG) is another molecule that has been implicated in the alteration of fat metabolism in cancer patients. ZAG, formerly known as lipid mobilizing factor, can be identified in the urine of cancer patients and has been found to strongly induce lipolysis (19).

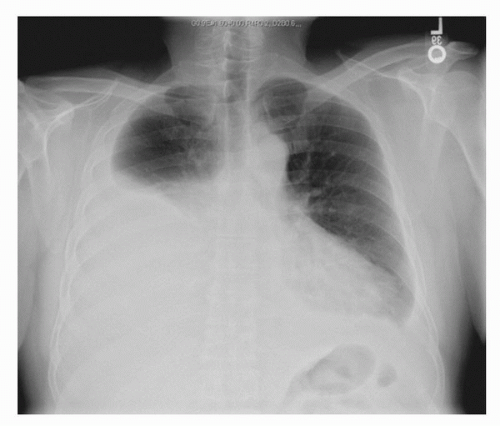

FIGURE 37.2. A chest x-ray from a patient who presented to his internist with progressive shortness of breath. He was found with a large left pleural effusion from RCC pleural metastases. |

Skeletal muscle breakdown in cachexia appears to be related to both alterations in protein synthesis as well as increased levels of protein degradation (20). The ubiquitin-proteosome pathway accounts for the majority of skeletal muscle breakdown associated with cancer (21). Several cytokines including TNF-a, IL-6, and proteolysis-inducing factor are known to stimulate this pathway in cancer leading to increased skeletal muscle degradation (19,20,22).

Weight loss is a common feature in patients with advanced RCC and may present in up to 25% of patients (6,12). However, patients with localized T1 tumors may also report significant weight loss, and in these rare cases (˜8%), the presence of cachexia-related symptoms may independently predict worse prognosis (11).

Pulmonary

The most common extraperitoneal site of distant tumor spread from RCC is the lungs. Lesions can develop within the lung parenchyma, in mediastinal nodes, or as pleural-based nodules. With pulmonary metastases, patients may present with a variety of thoracic symptoms, including cough, pleuritic chest pain, or dyspnea. Shortness of breath may be also observed in patients with RCC and can be caused by large pleural effusions (Fig. 37.2). A diagnostic thoracentesis can be performed to obtain fluid for cytologic evaluation. Patients with pleural metastases can develop high-volume effusions that may necessitate frequent drainage and/or sclerosis. Rarely, patients with localized disease may present with complaints of cough which invariably dissipates after resection of the primary tumor.

Occasionally, patients may present with pulmonary emboli. The formation of these embolic foci are likely multifactorial, and could be related to the classic Virchow hypercoagulable state associated with malignancy, but may also be related to the development of an invasive tumor thrombus. Because tumor thrombi usually represent a somewhat organized lattice of vascular tumor, embolization rarely occurs. Bland thrombus, on the other hand, can develop due to turbulent flow and venous stasis, factors which may promote thrombus embolization. Patients presenting with an unexplained embolus and a history of flank pain should undergo abdominal imaging. Anticoagulation may be considered.

Bone Pain and Fractures

Because RCC has a predilection to spread to the bones, bone pain or pathologic fractures can be the presenting sign. Bone metastases from RCC tend to be osteolytic and can be quite destructive when extensive. RCC often preferentially spreads to the femur, pelvis, and axial skeleton (23). Bone metastasis can be quite debilitating to patients and performance status may be significantly impacted due to poor mobility (24). In a recent study by Shuch et al., the presence of bony metastases was found to strongly influence performance status PS; patients who had an ECOG performance status of two thirds demonstrated bone involvement nearly three times more often than patients who had an ECOG PS of 0 (25). However, impacted PS secondary to bone metastases may not be as ominous as impaired PS due to visceral metastases. For example, in patients undergoing cytoreductive nephrectomy, those who had a poor performance secondary to severe bone involvement were found to have an improved outcome compared with patients who had other factors that caused a decline in performance (25). These data highlight the importance of proper pain management with narcotics which may subsequently influence a patient’s treatment plan.

Neurologic Sequelae and Seizures

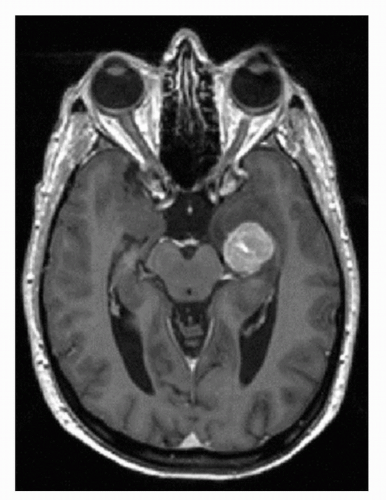

Brain metastases are commonly observed in patients with metastatic RCC with an incidence of 2% to 17% (26,27,28,29). These lesions are often associated with significant peritumoral edema, are highly vascular, and are susceptible to hemorrhage (Fig. 37.3) (30,31). Both localizing and

nonlocalizing CNS symptoms may be observed in subjects presenting with CNS metastases. Brain metastases tend to be symptomatic rather than incidental findings, and symptoms have been reported in 80% to 98% of patients and may include headaches, confusion, altered behavior, and seizures (32,33). Recently, with increased screening for brain metastases in subjects presenting with metastatic disease, more asymptomatic tumors are being discovered; the size of the lesion appears to determine symptoms as well as appropriate treatment modality (32).

nonlocalizing CNS symptoms may be observed in subjects presenting with CNS metastases. Brain metastases tend to be symptomatic rather than incidental findings, and symptoms have been reported in 80% to 98% of patients and may include headaches, confusion, altered behavior, and seizures (32,33). Recently, with increased screening for brain metastases in subjects presenting with metastatic disease, more asymptomatic tumors are being discovered; the size of the lesion appears to determine symptoms as well as appropriate treatment modality (32).

Clear cell RCC has a tendency to spread to the brain in advanced disease, and management of CNS metastases represents an urgent priority (32). Brain lesions from RCC are frequently symptomatic due to their hemorrhagic and edematous nature. Symptoms depend on the size as well as the location of the metastases. Patients frequently complain of headaches, visual changes, seizures, or loss of balance. Brain lesions may need to be treated prior to the initiation of systemic therapy due to concerns for bleeding. Recently, National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines have proposed stereotactic radiosurgery as an option for the management of small (<2 cm), asymptomatic CNS metastases (34). Craniotomy or whole-brain radiotherapy may be required for larger or multiple lesions. Shuch et al. retrospectively identified that 138 of 1,855 (0.075%) patients with RCC had brain metastases (32). A solitary lesion was observed in 68.1% with an average size of 1.8 cm. Overall, only 33% of patients were asymptomatic. However, the mean size of asymptomatic lesions was 1.3 versus 2.1 cm for symptomatic lesions (p < 0.001). Based on the findings of this study, we recommend that all patients with metastatic RCC should receive initial CNS screening because if CNS tumors are present, the smaller size of asymptomatic tumors makes them more amenable to minimally invasive treatment options.

Patients with spinal cord metastasis can develop cord impingement (Fig. 37.4). The classic signs of cord compression include back pain, change in urinary and bowel habits, and lower extremity paralysis and paresthesias. These patients require urgent intervention such as radiotherapy or surgical decompression to prevent irreversible damage.

PARANEOPLASTIC SYNDROMES

Hypertension

Hypertension occurs in 14% to 40% of patients with RCC (35,36). Hypertension may precede the diagnosis of RCC by several years (37). Hypertension is often but not exclusively associated with low-grade, clear cell tumors (38). Nonparaneoplastic modes of hypertension include parenchymal compression via a Page effect, ureteral obstruction, and arteriovenous fistulae. Putative paraneoplastic mechanisms include secretion of vasoactive peptides (such as renin, endothelin-1, urotensin-II, and adrenomedullin), polycythemia, and rarely nor-adrenaline production (35,39,40,41,42,43). Additionally, a large bulky tumor can either compress hilar vessels or normal parenchyma leading to increased activation of the renin-angiotensin system. Following nephrectomy, hypertension resolves in approximately 85% of patients (38,40).

Hepatic Dysfunction and Jaundice/Stauffer Syndrome

An unusual presentation of RCC includes the development of abnormal liver function tests (LFTs). The presence of bulky liver metastases (Fig. 37.5) can cause elevations in LFTs; however, there is an additional paraneoplastic cause, first termed “nephrogenic hepatosplenomegaly” (44). This finding, now known as Stauffer syndrome, can occur in both metastatic and localized disease in up to 30% of patients (6). Patients with Stauffer syndrome may present with hepatosplenomegaly, fever, and weight loss. Approximately, two thirds of patients demonstrate elevation in transaminases, alkaline phosphatase, and prothrombin time; a subset of patients may have elevated levels of bilirubin and gamma globulin (45,46). The hepatic dysfunction is generally mild; however, patients can present with jaundice and coagulopathy. Histologically, the hepatitis is characterized by lymphocytic infiltration and hepatocellular degeneration. Despite a comprehensive workup, patients may have no definitive explanation for their abnormal liver LFTs. After resection of localized disease, however, these patients can be anticipated to demonstrate normalization of laboratory abnormalities.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree