Secondary Tumors

Mikhail Lisovsky

Amitabh Srivastava

INTRODUCTION

Secondary epithelial tumors may involve the stomach through direct contiguous spread, hematogenous metastasis or as a result of peritoneal seeding. Metastasis to the stomach due to hematogenous spread is uncommon and the reported prevalence varies from 1.7% to 5.4%.1, 2, 3 and 4 The higher prevalence reported in more recent studies is possibly a reflection of increased use of upper endoscopy and biopsy for evaluation of solid tumor patients with upper gastrointestinal symptoms. Malignant melanoma appears to have the highest propensity for gastric metastasis among solid tumors. Other common primary tumor sites include the breast, lung, and esophagus. Metastasis to the stomach is reported in 22% to 30% of malignant melanomas, 2.4% to 15.2% of esophageal cancers, 5.9% to 11.6% of breast carcinomas, and 2.4% to 6.8% of lung carcinoma patients.3,5, 6, 7, 8, 9 and 10 However, since the prevalence of lung and breast cancer in the general population is much higher than that of malignant melanoma, breast and pulmonary carcinomas are the most common primary sites of gastric metastasis encountered in daily practice.11,12 Metastases originating from other organs have also reported as rare case reports and small series and include the kidney, ovary, liver, pancreaticobiliary tract, uterus, bladder, colon, prostate, testis, head and neck, and bone and soft tissue tumors.2,3,13, 14, 15, 16, 17 and 18

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

In autopsy studies of gastric metastases from solid tumors, slightly over half of all cases were clinically symptomatic.2 Diffuse abdominal pain was the commonest presenting symptom, but patients also presented with nausea and vomiting, anorexia, guaiac-positive stools, or upper gastrointestinal bleeding. In most patients, the diagnosis is usually straightforward when a prior diagnosis of another solid tumor is known. Pulmonary and esophageal metastases are usually diagnosed within a year of the diagnosis of the primary malignancy. However, the latency may be longer in cases of breast carcinoma where nearly half of the gastric metastatic lesions are diagnosed after >3 years.3 In nearly 50% of patients with gastric metastasis, there is also concomitant involvement of another site.17 In rare instances, the gastric metastasis may be the initial manifestation of a visceral malignancy.3 The distinction between primary and metastatic gastric tumors is critical because it affects the choice of chemotherapeutic regimen and the patient prognosis. Metastasis to the stomach is typically a marker of advanced malignant disease, and the median survival for these patients is <12 months.14,17

Metastatic lesions often produce a characteristic “bull’s-eye” or “target” appearance with a bridging mucosal fold on radiographic examination. The filling defect with a central collection of barium is often related to central necrosis in the tumor and the bridging mucosal fold is indicative of the submucosal tumor location. However, this sign is not highly sensitive and in one series it was present in only 44% of the cases.3 Nevertheless, if multiple “bull’s-eye” lesions of varying sizes are present, the diagnosis is most likely to be a metastatic tumor. Other lesions that may produce

a similar appearance on radiology include a lymphoma, heterotopic pancreas, carcinoid tumor, submucosal mesenchymal tumors or hemorrhage, and even primary carcinoma of the stomach. On endoscopy, metastatic tumors show surface ulceration and are often described as “volcanolike,” “umbilicated,” or “heaped-up” lesions. When solitary, this may mimic the appearance of a primary gastric carcinoma.3,17 Metastatic lesions may sometimes be completely submucosal with a smooth overlying mucosal surface similar to the appearance seen in gastric gastrointestinal stromal tumors or show diffuse gastric infiltration without a visible mass lesion mimicking linitis plastica. Diagnosis may be difficult in these latter instances and multiple, deep biopsies may be necessary for definite diagnosis. It is, therefore, not surprising that up to 30% of endoscopic biopsies are reported to be false negative in some studies, especially in the setting of metastatic breast cancer with diffusely infiltrative pattern of invasion.14 However, others have shown that endoscopy with biopsy can confirm the diagnosis of a metastatic tumor in 90% of cases.3

a similar appearance on radiology include a lymphoma, heterotopic pancreas, carcinoid tumor, submucosal mesenchymal tumors or hemorrhage, and even primary carcinoma of the stomach. On endoscopy, metastatic tumors show surface ulceration and are often described as “volcanolike,” “umbilicated,” or “heaped-up” lesions. When solitary, this may mimic the appearance of a primary gastric carcinoma.3,17 Metastatic lesions may sometimes be completely submucosal with a smooth overlying mucosal surface similar to the appearance seen in gastric gastrointestinal stromal tumors or show diffuse gastric infiltration without a visible mass lesion mimicking linitis plastica. Diagnosis may be difficult in these latter instances and multiple, deep biopsies may be necessary for definite diagnosis. It is, therefore, not surprising that up to 30% of endoscopic biopsies are reported to be false negative in some studies, especially in the setting of metastatic breast cancer with diffusely infiltrative pattern of invasion.14 However, others have shown that endoscopy with biopsy can confirm the diagnosis of a metastatic tumor in 90% of cases.3

PATHOLOGY

Macroscopic Features

Macroscopic features of metastatic tumors to the stomach are often nonspecific and may mimic a primary gastric malignancy. Some subtle findings may, at times, point to a specific diagnosis. Multiple, small black spots may be visible in cases of metastatic malignant melanoma but can easily be mistaken for old intratumoral hemorrhage unless the observer is aware of the clinical history. The usual gross appearance of metastatic tumors is that of an ulcerating or fungating mass lesion that mimics Borrmann Type II or III patterns of primary gastric cancer. The diffusely infiltrative Borrmann Type IV pattern is also sometimes seen in cases of metastatic breast or lung cancer. Almost two thirds of metastases present as solitary lesions, which enhances the likelihood of misdiagnosis as a primary gastric tumor. The greater curvature is a common site of involvement, regardless of whether one or multiple metastatic lesions are present in the stomach.17 Most lesions are present in the middle or upper third of the stomach, which contrasts with the predominant antral location of primary gastric cancer in the setting of Helicobactor pylori gastritis seen in endemic regions. Submucosal involvement is always present and large tumors may show transmural spread involving the mucosa and serosa. Gynecological malignancies may spread to the stomach by way of peritoneal seeding. Multiple serosal deposits of tumor are present in these cases that may extend into the wall of the stomach all the way up to the mucosa.

Microscopic Features

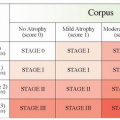

The common intestinal type of gastric cancer arises through an inflammation-atrophy-metaplasia-dysplasia-cancer pathway. H. pylori gastritis and, to a lesser extent, autoimmune gastritis are the most common inflammatory conditions associated with increased risk of gastric adenocarcinoma. Thus, the lack of inflammation or atrophy in the background nonneoplastic mucosa and the absence of a dysplastic precursor lesion adjacent to the tumor should raise suspicion for a metastatic carcinoma. Multiple serosal deposits or predominant submucosal or intramural localization of the tumor also favors secondary tumor involvement over a gastric primary. The morphological features specific to metastases from specific organ sites, their overlap with primary gastric carcinoma, and the role of ancillary immunohistochemical studies in arriving at a definite diagnosis are discussed in greater detail below.

BREAST CARCINOMA

Metastasis from breast cancer is not only one of the most common primary sites of origin but also one of the most challenging diagnostic scenarios. Invasive lobular carcinoma is the source of the majority (70%-75%) of metastatic breast cancer to the stomach.14,19,20 The distinction between diffuse-type gastric cancer, which typically arises de novo, from metastatic

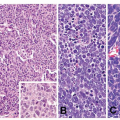

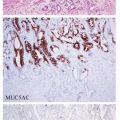

lobular-type breast cancer is extremely difficult morphologically since both tumors show single cell infiltration and cytoplasmic lumen formation. Lack of a clinical history of breast cancer does not completely rule out the possibility of a metastatic carcinoma because rare cases of gastric metastasis as the first manifestation of an occult breast cancer have been reported.21 Similarly, knowledge of a history of breast cancer is helpful but not sufficient for definite diagnosis because the gastric tumor may be a second primary. In a recent meta-analysis of 19,049 breast cancer survivors, 28 (0.15%) gastric malignancies were reported on follow-up. Eleven of these twenty-eight (39.3%) were primary gastric adenocarcinomas, and only 4/28 (14.3%) were metastases from the prior breast primary.22 Tamoxifen use has been suggested to increase the risk of subsequent gastric cancer but a recent study failed to confirm this association. The authors did find, however, that the latency between the initial breast cancer and the second gastric primary appears to be significantly reduced in tamoxifen users as compared to those not exposed to tamoxifen. The reported latency was 4 years in tamoxifen users as compared to 13 years in nonusers in this study (Figs. 8-1, 8-2, 8-3 and 8-4).23

lobular-type breast cancer is extremely difficult morphologically since both tumors show single cell infiltration and cytoplasmic lumen formation. Lack of a clinical history of breast cancer does not completely rule out the possibility of a metastatic carcinoma because rare cases of gastric metastasis as the first manifestation of an occult breast cancer have been reported.21 Similarly, knowledge of a history of breast cancer is helpful but not sufficient for definite diagnosis because the gastric tumor may be a second primary. In a recent meta-analysis of 19,049 breast cancer survivors, 28 (0.15%) gastric malignancies were reported on follow-up. Eleven of these twenty-eight (39.3%) were primary gastric adenocarcinomas, and only 4/28 (14.3%) were metastases from the prior breast primary.22 Tamoxifen use has been suggested to increase the risk of subsequent gastric cancer but a recent study failed to confirm this association. The authors did find, however, that the latency between the initial breast cancer and the second gastric primary appears to be significantly reduced in tamoxifen users as compared to those not exposed to tamoxifen. The reported latency was 4 years in tamoxifen users as compared to 13 years in nonusers in this study (Figs. 8-1, 8-2, 8-3 and 8-4).23

In metastatic breast cancer, more than half of the cases show diffuse infiltration of the stomach, mimicking the linitis plastica appearance of diffuse-type gastric cancer. Only a minor subset of metastases present as localized gastric lesions. There is a wide spectrum of nuclear features seen in these cases. Foci typical of lobular-type breast cancer with small, round nuclei and bland monomorphic nuclei are present in most cases. However, some cases show marked nuclear hyperchromasia, open chromatin with prominent nucleoli while retaining the single cell infiltration pattern of lobular carcinoma. The distinction between metastatic breast cancer and a second gastric primary can be particularly challenging in these latter instances.

The diagnostic dilemma is further compounded by reports in the literature of estrogen receptor (ER)-positive gastric carcinoma. The reported prevalence for this phenomenon was up to 50% in some studies and did not correlate with patient gender.22,

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree