Advanced Colon Cancer

A small but significant number of patients for whom a curative operation was planned have big bulky tumors that extend beyond the intestinal wall and adhere to adjacent tissues or organs. When colon cancer has grossly invaded or has densely adhered to an adjacent organ in the absence of distant metastasis, it is called advanced colon cancer, which represents approximately 10% of all colorectalcancers.6–10 Advanced colon cancers can present with lymph node metastasis (Dukes C2 or Astler–Coller T4N1–2) or without lymph node metastasis (Dukes C1 or Astler–Coller TNO). Almost half of these tumors are node-positive. Many locally advanced cancers, even if they are large in size or attached to other organs, are potentiallycurable with surgery, especially if the regional lymph nodes are free of metastases, which is surprisingly frequent.7

In 1959, Butcher and Spjut reported a variant of a very large, bulky colon cancer, which did not tend to metastasize to lymph nodes even though it invaded adjacent organs.11 Spratt et al. analyzed 1137 consecutive colorectal patients and found that of the largest resected colorectal carcinomas (more than 13 cm in diameter), 66.7% had no metastases in resected lymph nodes.12 Although these tumors tend to penetrate the intestinal wall, grow to a large size, and occupy the adjacent tissues or organs, they remain localized for long periods without spreading to regional lymph nodes and appear to be curable by aggressive resection. This biologic behavior is unlike that of most other epithelial tumors in which locoregional invasion is usually associated with contiguous regional or distant metasta ses, as is particularly true of other gastrointestinal adenocarcinomas.7

The sigmoidcolon and rectum are the mostcommon locations for locally advanced colon cancer.8 Thus, extracolonic extension more often occurs in sigmoid colon and rectum where pelvic structures and organs may be involved.13 Locally advanced carcinoma of the right colon and proximal transverse colon adhere to adjacent organs in as many as 11 to 28% of cases.10,14Right-sided carcinomas of the colon can invade the small bowel, abdominal wall, the right kidney, ureter and bladder, genital organs (uterus, fallopian tubes, and ovary), duodenum, pancreas, and liver. Extensive surgical procedures have been performed to completely resect locally advanced primary colon cancers, and multivisceral en bloc resection of these tumors has resulted in cure in many patients.15,16

En Bloc Resection

En Bloc Resection

Resections for colon cancers are categorized as follows: R0, all gross disease resected by en bloc resection with margins histologically free of disease; R1, all gross disease resected by en bloc resection with margins histologically positive for disease; R2, residual gross disease remains unresected.5

Curative surgery must always follow the oncologic criteria of an en bloc resection established for the treatment of colorectal cancer. Unless en bloc resection is surgically and pathologically confirmed in a patient (R0 resection), the resection cannot be considered curative.5 True tumor infiltration is generally confirmed pathohistologically in 43 to 70% of patients, whereas the remaining tend to have only inflammatory changes that mimic tumor invasion.17–20 In a recent study, the true infiltration rate was observed in only 116 (34%) of 341 patients.18 These findings may lead some to suggest that the colon may be separated from a structure that has been adhered to the colon cancer, since these infiltrations are not always associated with malign invasions, but when this concept was followed, the local recurrence rate was 26% and the 5-year survival rate was only 30% in 35 patients, probably because dissection caused dissemination of tumor cells. 18,21 Other studies have revealed similar results. In a group of 43 patients with adjacent organ involvements, local recurrence rates were exceedingly high when adherent organs were separated from the tumor (77 vs. 36%).22 Conversely, the 5-year survival was significantly higher when an en bloc technique was performed (61 vs. 23%).22 In two studies, early recurrence was reported in 70–100% of the patients treated with non en bloc resections.22,23 Hunter et al. reported that en bloc resection of colorectal cancers that are adherent to other organs resulted in local recurrence and 5-year survival rates that were comparable with the stage-matched nonadherent colorectal cancers.6 En bloc resection is now considered mandatory for curative colon cancer surgery because it reduces recurrence and maximizes the 5-year survival rates. An en bloc resection is warranted even for patients with regional lymph node metastases (the most important prognostic factor after potentially curative resection for colorectal carcinoma and adjacent organ involvement).5,23

Therefore, any attempt to separate the colon cancer from the adherent organs should be discouraged because it could lead to the dissemination of cancer cells into the abdomen, which increases the risk of recurrence. Similarly, finger-fracture separation of densely adherent viscera should be avoided because it can preclude cure.24,25 With regard to the surgical approach for adherent carcinomatous masses, en bloc resection is an absolute necessity, because any effort to separate the carcinoma from neighboring organs will tear or transect the tumor and increase the attendant risk of intraoperative dissemination resulting in a significant and unacceptable worsening of the prognosis.10,14,23

Preventing Inadvertent Perforations

Preventing Inadvertent Perforations

Inadvertent perforations during resection are not uncommon. The rectum is the most common location for accidental perforation, but it can occur during the resection of right colon tumors. Yu found that although tumor cells readily implant on traumatized serosa, the intact intestinal mucosa is quite resistant.26 Bowel wall injury exposes the intraluminal bowel contents with its desquamated cancer cells to the traumatized fresh planes opened by surgicaldissection. Gall et al. revealed that in 44 patients with positive tumor infiltration and multivisceral en bloc resection without tear or rupture of the tumor, the 5-year survival rate was 49%, which decreased significantly to 17% when the surgeon inadvertently tore or cut into tumor tissue during dissection.17 Slanetz Jr reported a reduction in 5-year survival and an increase in local recurrence rates after inadvertent perforations during colon cancer surgery.27 Therefore, during the surgical dissection of the tumor, the surgeon must be careful not to inadvertently perforate the tumor.

Extent of the Resection

Extent of the Resection

The extent of the resectionis one of the most important factors affecting cancer recurrence. Little controversy exists about the dissection margins in colon cancer. The ideal extent of bowel resection is defined by removing the blood supply and lymphatics at the level of the origin of the primary feeding arterial vessel.5 When the primary tumor is equidistant from two feeding vessels, both vessels should be excised at their origin.5

The margin distal to the primary tumor is determined by the adequacy of the blood supply to the distal colon for anastomosis after appropriate vascular ligation, the downward lymphatic spread, and the intramural spread of the carcinoma.28 Intramural spread of the tumor occurs through the submucosal and intramural lymphatics or perirectal fat.29 Distal intramural spread rarely exceeds 4 cm even in the most unfavorable cases.29 Recent studies have revealed that only 2.5% of patients will have tumors that have spread more than 2 cm, and these are generally anaplastic or poorly differentiated node-positive cancers.2 Although there is some debate, 5 to 10 cm of normal bowel on either side of the primary colon tumor appears to be a minimum length to prevent anastomotic recurence.5,30,31 The length of resected ileum does not appear to affect local recurrence. Therefore, the shortest length of ileum needed to perform the surgical procedure should be excised to prevent malabsorption syndromes.5 With regard to histologic assessments of distal margin, all margins must be microhistopathologically evaluated with a review of permanently fixed or frozen tissue sections.

Lymph node resection carries with it prognostic and therapeutic implications.5 Tumor invasion to the lymph nodes directly affects survival rates in patients with advanced colon cancer. In a study of 58 patients with advanced colon cancers, Eisenberg et al. found that the mean survival and 5-year disease-free survival rates were 100.7 months and 76% for lymph-node negative patients respectively whereas they were 16.2 months and 0% for lymph-node positive patients respectively.25

An appropriate lymph node resection should extend to the level of the origin of the primary feeding vessel. As with the primary tumor, the lymph nodes should be removed en bloc. Lymph nodes at the origin of feeding vessels (apical nodes) should be removed when feasible and tagged for pathologic evaluation. Lymph nodes suspected of being positive for disease outside the field of resection need to be sampled or biopsied. If biopsy results of the suspected lymph nodes are positive for disease and the lymph nodes are resected with the apical nodes or the biopsy results are negative, the resection is considered to be a curative resection (R0 resection).5 Otherwise the procedure is an incomplete resection for cure (R1 or R2 resections).5 The apical node may also have prognostic significance in addition to the number of lymph nodes positive for disease in the specimen.32 To achieve a high degree of accuracy (>90%), a minimum of 12 lymph nodes negative for disease must be examined to confirm that the disease does not involve the nodes.33 Several retrospective studies have yielded conflicting results on the value of extended lymphadenectomy.5,34,35

No-Touch Technique

No-Touch Technique

It has long been suspected that cancers may be disseminated through the bloodstream by the trauma of surgical removal. Viable tumor cells have been found in peripheral venous blood of patients whose colorectal cancer was intraoperatively manipulated.36,37

In 1952 Barnes described a special technique for resecting the right colon cancer in which the vascular pedicles are ligated and the bowel is divided before the cancer-bearing segment is handled.38 Turnbull et al. demonstrated a difference in 5-year survival in a retrospective analysis.39 In the only prospective randomized trial no statistical difference was observed in 5-year survival with the use of the no-touch technique in 236 patients (31.1% disease-related death in the conventional arm, 24.7% disease-related deaths in the no-touch technique); but the time to appearance of liver metastases was lower and the number of liver metastases was higher in the conventionalarm.40 The value of the no-touch technique has been debated.

Because malignant cells have been found within the lumen of the colon after operative manipulation, it is possible that viable tumor cells implant in the anastomotic line and cause recurrence in the suture line.37 Therefore, at least one study recommended occluding the proximal and distal parts of primary tumor by ligating the colon externally with cotton tapes before manipulating the tumor.37 No studies have been performed to evaluate the outcome of this technique.

Multivisceral Resection in Locally Advanced Right Colon Cancer

Multivisceral Resection in Locally Advanced Right Colon Cancer

Colorectal cancer invades adjacent organs in 5.5–16.7% of all colorectal malignancies.6–10,13,41,42 Because a high percentage of very large T4 tumors have not yet metastasized to the regional lymph nodes, a multivisceral resection offers radical removal of the local disease and results in cure.19 Multivisceral resection of colon cancer is defined as en bloc removal of any organ or structure to which the primary tumor is adherent. Removal of unattached organs (e. g., liver resections for hepatic metastases, cholecystectomy for symptomatic gallbladder disease, splenic resection for iatrogenic injury, and resection of synchronous tumors) is not considered multivisceral resection.18 The aim of multivisceral resection is an en bloc removal of the primary tumor and adherent organs or structures (R0 resection) without leaving any microscopic (R1 resection) or macroscopic (R2 resection) disease, in which survival and recurrence rates are unacceptable.

The invasion of colon cancer to other organs is rarely recognized before surgery. Most patients with colonic cancers who required extended resections have gastrointestinal tract symptoms such as anemia, weight loss, abdominal pain, nausea and vomiting, or diarrhea, but there is no correlation between any symptom or combination of symptoms and the presence of pathologic invasion of contiguous structures.8,14,43,44 Pneumaturia and vaginal bleeding are pathognomonic, but they are extremely rare.45 Polk emphasized that many right-sided carcinomas with contiguous organ involvement are palpable preoperatively, and that when a tumor is palpable and immobile, adjacent structures are most likely involved.9,44

The final decision for multivisceral resection is made at the time of laparotomy. However, the surgeon cannot distinguish between malignant and inflammatory adhesions. The adherence represents true malignant invasions of the contiguous organ in 36 to 70% percent of cases.15,18,21,46,47 Intraoperative assessment should rarely be used to exclude a patient from multivisceral resection with curative intent because the postoperative pathohistologic examination reveals disease-free margins in many specimens in which the surgeon considered tumor resection to be incomplete.18 Lehnert et al. encouraged surgeons not to decide intraoperatively to give up a resection because the inflammatory or malignant character of the adhesions during the laparotomy is not reliable and has a high negative predictive value.18 They suggested that surgeons should make every effort to completely resect the invasive tumors with the adherent tissues.18 In another series, re-exploration was performed in 52 consecutive patients who had originally been classified as having unresectable disease. An extended resection was performed in 32 of them, with a 5-year survival rate of 36%.48 Thus, the surgeon should perform an en bloc, complete resection of the tumor with adjacent tissues unless it is obviously not possible to achieve a R0 resection.

Determining the nature of a dense adherence between a tumor and closely apposed organ is difficult. Attempts to biopsy tissues between colon cancer and an adherent organ may give false-negative results due to sampling error and more importantly can lead to tumor spillage. Thus, intraoperative frozen section should be avoided to determine the extent of resection in order not to cause tumor contamination.18 When the surgeon suspects that the adherent tissue is microscopically invaded, en bloc resection is the best choice, because the differentiation of benign from malignant adhesions is inaccurate and because intraoperative biopsy risks tumor dissemination.24 The nature of the adherence between the primary tumor and adjacent viscera should be determined only upon histologic assessment of the extended resection specimen.9

Before undertaking a major procedure such as multivisceral resection, the following issues should be kept in mind: the patient’s condition, stage of the tumor, experience of the surgical team, operative factors, and postoperative outcome.13 High-risk, unstable, elderly, and malnourished patients may not be good candidates for multivisceral resections. Although contentious, a recent study revealed that elderly patients, who had multivisceral resection procedures survived for a significantly shorter time than the younger patients.18 The surgeon should remember that emergency operations are associated with worse outcomes when compared with elective multivisceral resections.18 During laparotomy, peritoneal or liver metastasis must be ruled out before attempting a resection because patients with metastases would not benefit from multivisceral resections.49

Multiorgan resection for locally advanced colon cancers is not a standardized procedure. The following sections will attempt a standardization. In addition, the decision to perform multivisceral resection is usually made at the time of surgery because the need for multivisceral resection is rarely recognized before surgery for colon cancer. Therefore, good judgment is required as premature or irreversible steps that mandate an extended, but clearly palliative resection are best avoided. In this situation, it is important to evaluate the accuracy with which curative or palliative outcome of the treatment can be predicted during surgery. Long-term results are poor if en bloc resection of the primary tumor with any organ or structure to which it is adherent is not achieved.50 It has been shown that mean survival is only 14 months in resections with histologically positive margins for disease, which is an extremely short amount of time.8,50 Therefore, when dealing with a colorectal cancer that is adherent to adjacent organs, the surgeon must determine the resectability of the tumor. If the surgeon determines that the tumor is resectable, efforts must be made to perform an appropriate resection.13

Variations in surgical technique are the most important determinants of cancer recurrence and survival. Experience is needed to determine which surrounding organs are affected. If the surgeon is not familiar with the procedure, the abdominal wall should be closed and the patient referred to a specialized center.13 A surgeon with limited experience may consider the tumor to be unresectable and prefer a palliative bypass as the only alternative for the patient, which would reduce his or her chance for cure.13

Specific Organ Involvements

Specific Organ Involvements

The small bowel is the most common location of invasion; it is the affected organ in 15 to 25% of all cases with right colon cancer.6,18,50 Generally, segmental resection with an adequate tumor-free margin and anastomosis is the choice of treatment. The abdominal wall is also a frequent location for tumor invasion.6,50 The tumor infiltration rate of abdominal wall invasion is generally lower than that of other adherent organs.18 Therefore, a small portion of peritoneum generally must be removed to obtain tumor-free margins. If the tumor invades a wide area such as the skin and underlying structures, a rare occurrence, a large en bloc removal of abdominal wall is needed.51 If the surgeon has doubts about the subsequent abdominal closure that should never influence him or her to be less than thorough in the debridement or to accept less than adequate tumor resection, patient survival must always be the paramount consideration.52 Mesh repair can be used in these patients. In patients who have a primary fascial closure without a mesh, the wound can be left open and closed in a delayed primary fashion.52,53

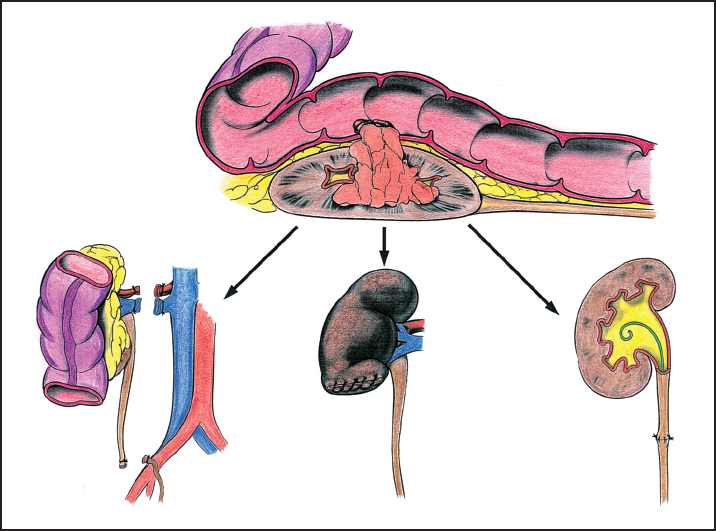

Larger tumors may also invade urinary tract organs including the kidney, ureter, and bladder. In this case, the affected organ must be resected to achieve cure.13,14,18 Complete tumor resection with en bloc partial or total nephrectomy can be performed.53 Occasionally, in bulky tumors, the ureter may appear to have been invaded by tumor. In this situation, the surgeon must assess if it is in contact with the tumor or encircled by it. In the former case, a careful dissection usually shows that it is not involved and can be separated. In the latter case, a resection is imperative. If a small portion of the ureter is invaded, an anastomosis can be safely done over a ureteral catheter after a partial ureteral removal (Fig. 8.1). If a long portion of ureter is removed or the resection site is near to the bladder, the reconstruction can be made with an ureteoneocystostomy.54 Another technique for the reconstruction of missing ureter includes a defunctionalized segment of ileum anastomosed proximally to the proximal segment of ureter and distally to the bladder.55 Bladder invasion can be managed by removing the involved portion of the bladder with a 2-cm tumor-free margin.14,54

Right colon tumors rarely invade the genital organs, uterus, fallopian tubes, and ovaries.18 Although there are no current data to support routine prophylactic oophorectomy, en bloc or complete resection of the ovary is recommended if the tumor has obviously and directly invaded the ovary or if the ovary has a grossly abnormal appearance.5 The incidence of synchronous ovarian metastases varies from 2 to 8%.54 Because of the higher prevalence of ovarian cancer among women with colorectal cancer, oophorectomy may be performed in postmenopausal patients or in premenopausal patients who do not have a desire to conceive.54 During the resection of these structures, the surgeon should strive for a tumor-free margin, which is the most important factor affecting survival and recurrence of the tumor.

Fig. 8.1 When the kidney is invaded with a large tumor, complete tumor resection with en bloc partial or total nephrectomy can be performed. If the ureter is invaded, a partial removal is required and then an anastomosis can be safely done over a ureteral catheter in most cases.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree