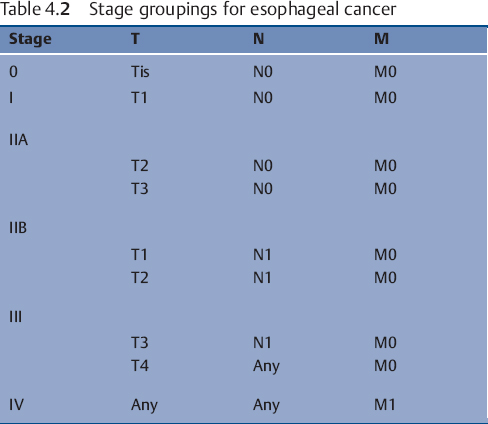

Table 4.1 TNM Staging of esophageal carcinoma

In determining which operation is best for potential curative resection of esophageal cancer, there are three main concerns: the radial margin of resection, the longitudinal margin of resection, and the extent of lymphadenectomy. Since many operations for esophageal cancer are unlikely to cure patients with esophageal cancer, there must also be proper consideration of palliative issues as well. The same concerns about resection apply to palliative procedures as to curative procedures but other factors such as involvement of adjacent organs must be considered as well. In the absence of metastatic disease, patients with direct extension of tumor into adjacent viscera remain in the Stage III category (Tables 4.1 and 4.2 for TNM Classification and Stage Groupings). While survival for patients with stage III disease is worse than for those patients with lower stage disease, there are still a significant percentage of survivors reported at 5 years.1 Neither the stance of “nihilism” nor of “irrational exuberance” as regards the benefit, or lack thereof, of esophageal resection for cancer is supported by the literature. The series with the best reported outcomes show significant 5-year mortality for resection of all but Stage I disease and show some benefit to resection in all but the most advanced, Stage IV, patients. So the truth would appear to lie somewhere in between unbridled optimism and pessimism. In many cases the difference in patient outcome will depend upon the skill of the people caring for the patient more than the disease of the patient; but the most important skill may be choosing the correct operation for the right patient and then performing the operation correctly.

Extent of Resection

Extent of Resection

The desired extent of resection is predominantly judged on one of two criteria: survival advantage or anastomotic recurrence/local failure. The most consistently recognized prognostic factor portending a good long-term outcome is an R0 resection. To qualify as an R0 resection, the specimen must include the primary tumor and adjacent lymphatic tissue and have microscopically clear proximal, distal, and radial margins.2

The longitudinal margin of resection must address removal of the primary tumor plus any tissue that is likely to harbor intramural metastatic neoplasm. Multifocal disease or intramural metastatic disease is estimated to occur in as many as 25–30% of patients.3 Longitudinal clear margins of resection that are 10 cm or greater in length are associated with a chance of anastomotic recurrence that is less than 5%.4

Radial margins should also be microscopically free of tumor whenever possible. The ability to safely achieve this goal is somewhat dependent upon the location of the primary tumor. For those tumors located in the proximal portion of the esophagus, this may be achieved by en bloc resection of the proximal esophagus and the proximal airway structures with concomitant reconstruction.5 Tumors located below the tracheal bifurcation can be resected en bloc with adjacent structures such as pericardium, pleura, lung, periaortic tissue, thoracic duct, and azygos vein.6,7 Technical details of this will be discussed later in this chapter. For those tumors located in direct continuity to the trachea (unless superficial, T1 or T2) or in those with tumor penetration into the aortic wall or myocardium, R0 resections are unachievable. Therefore, proposed resection of these most locally aggressive of tumors is ill advised. Microscopic tumor involvement of any margin (R1) confers a significantly worse outcome probability with a higher likelihood of local failure.6

The last, and most controversial, factor in deciding extent of resection regards the degree of lymph node resection that is appropriate. This decision may also lead to discussion of which route of approach is best for esophageal resection as well. Lymphatic involvement in esophageal cancer is thought to happen early in the biological process. In patients in whom there is submucosal penetration of the primary tumor, lymphatic involvement is found in as many as 50% of patients. Involvement of the muscularis mucosae is associated with up to 30% lymph node metastasis.8,9 Intramucosal tumors are rarely associated with lymph node involvement. As a result of this recognized high occurrence of lymph node involvement with relatively superficial tumors, much interest has been generated in the extent to which lymph node dissection should be carried out. The three fields that are generally considered are the cervical nodes, the thoracic nodes, and the abdominal nodes. A two-field dissection usually refers to the thoracic and abdominal nodes. There is little controversy over the extent of abdominal lymph node dissection as it is a technically straightforward endeavor and confers little morbidity. The thoracic lymph node dissection is certainly only performed via a transthoracic approach. DeMeester and colleagues favored this approach as a superior operation in part because of its purported improved nodal clearance.10 While others, such as Orringer and colleagues, have suggested that the degree of lymphadenectomy may be more related to staging than prognosis and therefore have championed the transhiatal approach for esophageal resection.11 The benefit of cervical lymph node dissection is a little more difficult to assess. In a report from Japan, surgeons found that cervical lymph nodes were involved by metastatic tumor in up to approximately 46% of patients with proximal cancers, 28% with middle third cancers, and 28% with distal third cancers.9 These findings have generated a great deal of enthusiasm for three-field lymphatic clearance. Other Japanese studies have reported a survival advantage for three-field lymph node dissection over two-field lymphadenectomy.8,12,13 While randomized trials have shown a survival benefit trend, no statistical significance was attained.13,14 Nearly all of the patients in these reports had squamous cell carcinoma and whether or not this data correlates well with the population of patients who have adenocarcinoma of the esophagus is unclear.

Two western studies have been reported using three-field lymphadenectomy for adenocarcinoma of the esophagus. Both studies showed pathologic involvement of cervical lymph nodes (27 and 30%) and, in both series, the preponderance of tumors were located in the distal third of the esophagus.15,16 Neither study showed a survival advantage of three-field lymphatic clearance over two-field.

The three-field lymphadenectomy also has some substantial potential for concern. The cervical field nodal dissection is associated with significant morbidity, in particular related to the high incidence of inferior laryngeal nerve injury leading to vocal cord paralysis. This associated morbidity has been reported in as much as 70% of patients undergoing a cervical node dissection as part of a three-field lymphadenectomy.17 Given the profound negative effect on quality of life associated with vocal cord paralysis (especially if bilateral) in patients with either short- or long-term expectations for survival, one is faced with a potentially difficult ethical dilemma as a surgeon on whether to offer the additional nodal clearance. It would seem reasonable at this time to focus the efforts of three-field lymphadenectomy to centers with experienced operators and excellent ability to measure and track outcomes before widely recommending the adoption of this technique.

Lung and Airway Involvement

Lung and Airway Involvement

Invasion of the lungs or major airways by local extension of an esophageal cancer is frequently a harbinger of an ominous outcome. The more central the airway invasion the less likely that operative intervention will be associated with a satisfactory long-term outcome. Esophageal cancer can directly invade the major airways or the lung parenchyma itself. Pulmonary invasion by esophageal cancer must be clearly distinguished from metastatic disease to lung. Pulmonary or airway involvement may or may not be associated with fistulous communication between the esophagus and the bronchial system.

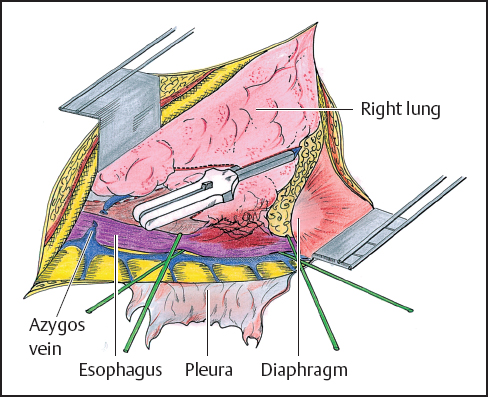

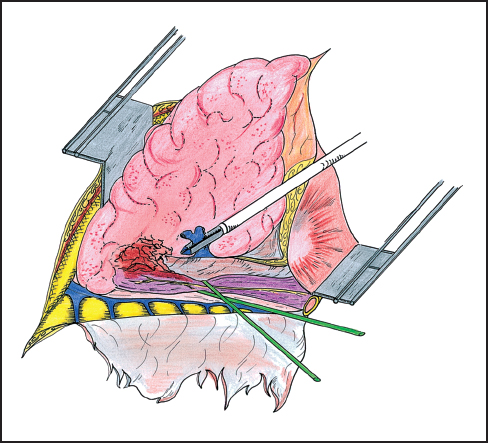

While direct extension of esophageal tumor to lung or airways is usually associated with imminent patient demise, there have been reports of operative management of patients in these precarious circumstances (Figs. 4.1, 4.2). In two reports from Japan, patients benefit from en bloc resection of esophagus with the affected lung tissue. In the first report, esophagectomy with concomitant resection of the affected lung was compared with esophageal resection without lung resection. The 5-year survival rates of the groups are 21.1 and 8.7%, respectively.18 A subsequent report evaluated patients who had either undergone a previous significant pulmonary operation or had undergone a concurrent pulmonary resection with esophagectomy. The authors conclude that major concomitant or previous pulmonary operation was not a contraindication to esophageal resection on the basis of survival rates of 92 and 45% at 1 and 3 years, respectively.19 The patient population in this study reflected only 18 patients and significant complications, though not fatal, were seen in 13 of these cases.

Fig. 4.1 Right posterolateral thoracotomy (see also p.58). The parietal pleura has been removed and the azygos venous system is exposed. The azygos vein is tied and cut. The esophagus is dissected and encircled with 2 Penrose drains. The lower lobe of the right lung is invaded by the tumor. Before completion of the proximal esophageal dissection, the lung parenchyma is stapled. It will be removed with the esophagus.

Fig. 4.2 En bloc right lower lobectomy and esophagectomy. The esophagus is exposed distal to the invasion of the lung parenchyma. The lower lobe is removed without opening the tumoral adhesions. After interrupting the right distal pulmonary artery, the pulmonary vein is here stapled. The lower lobe is then downward retracted and the proximal esophagus is prepared.

Matsubara and colleagues reported a series of 55 patients who were treated with esophagectomy and resection of a major airway structure over a 20-year period. Patients in whom resection was possible with clear margins and no lymph node involvement enjoyed the best results, 19% at 5 years.5 Whether or not the patients who had responded to neo-adjuvant therapy garnered additional benefit from the ensuing resection remains uncertain. One study from the United States shows less favorable long-term results but also favors resection for local control when technically feasible.20

Nonresective Therapy

Nonresective Therapy

No current discussion of esophageal resection can be complete without some discussion of the nonoperative components for treatment of the patient with esophageal cancer. The use of a multimodality approach is widely employed in both adjuvant and neo-adjuvant settings although its exact benefit is not yet fully agreed upon.

Preoperative radiation therapy alone is possibly associated with decreased local failure rates but its overall survival advantage has not been demonstrated.21–26 Postoperative radiation therapy has been suggested to reduce local failure in two trials but not to show survival advantage.27,28 In another trial utilizing postoperative radiation therapy, increased early death and morbidity were seen secondary to injury to the esophageal replacement conduit.29 Overall survival disadvantage was seen in the surgery plus radiation therapy group.

Neo-adjuvant chemotherapy has been shown to exert a significant downstaging effect on about 50% of patients with about 10% having a complete pathologic response.25,30–33 It is not clear whether this will show a long-term survival advantage. The usual chemotherapeutic regimens include cisplatin and 5-fluorouracil.

Neo-adjuvant chemoradiation is currently the preoperative therapy that we most employ for a patient in whom there is evidence to suggest a T3 or greater tumor or high likelihood of nodal involvement. While results of many trials are still pending, at least one trial shows a survival benefit to neo-adjuvant chemoradiation plus operation as compared to operation alone.34 However, some concerns have been raised about this study and the results of other studies will be needed to corroborate these findings.

At least one study may suggest that omission of operation, for squamous cell carcinoma, may be feasible. The Radiation Therapy Oncology Group Trial (85-01) evaluated cisplatin plus 5-fluorouracil given in adjunct with 50 Gy of radiation compared to 64 Gy of radiation alone.35 Significant benefit was seen in the combined therapy group and the trial was stopped before its estimated completion date. In a subsequent report,36 survival at 2 and 5 years was 36 and 27%, respectively. There were reductions in both local and distant failures. While toxicity from the treatment was high, 8% significant toxicity and 2% mortality, the group receiving chemotherapy and radiation fared far better than the group receiving radiation alone. We are, however, lacking in good randomized trials including chemoradiation and operative management at this time.

Operative Approach

Operative Approach

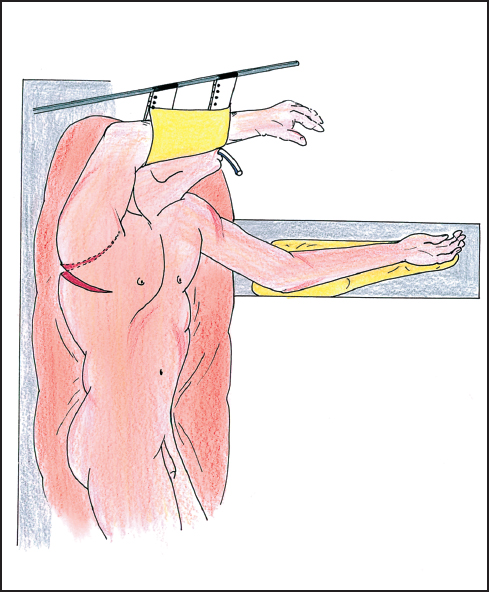

The approach for tumors of the esophagus is variable. One can approach these tumors through the abdomen, the chest, or some combination. Open and videoscopically-assisted approaches are also possible. Determination of which approach is best depends upon the location of the tumor and the desired position of the enteric anastomosis. For distal esophagectomy with anastomosis below the inferior pulmonary vein, a left thoracotomy via the fifth or sixth intercostal space can be used. The left thoracoabdominal incision can be used or an isolated abdominal approach, although the last can present a challenging anastomosis. If it is preferred to place the anastomosis above the superior pulmonary vein, then one can choose from a superior mediastinal or a cervical position. This holds for either gastric or colonic anastomoses and for free jejunal transfers. For anastomoses in the superior mediastinal position, the right thoracotomy is generally preferred (Fig. 4.3). This can be accompanied by an abdominal incision (Ivor-Lewis) or by a laparoscopic approach. If one chooses the cervical position for anastomosis, the approach will include a cervical incision accompanied by either a right thoracic approach or abdominal approach or both. There are reports of either videoscopic-assisted thoracic or abdominal components.

Transhiatal Approach

Transhiatal Approach

For tumors of the distal esophagus, we prefer the transhiatal approach utilizing an abdominal and cervical incision (Fig. 4.4). We prefer to use the stomach as the replacement conduit for the resected esophagus and create a cervical esophagogastrostomy to restore enteric continuity. Although leak from these anastomoses is uncommon, if it were to occur, it is thought to be less consequential and easier to treat if the leak occurs in the neck rather than the mediastinum. We have tended to avoid the temptation for limited resection of the distal esophagus and proximal stomach with lower thoracic esophagogastrostomy to avoid the postoperative problems associated with gastroesophageal reflux that frequently ensue. One of the advantages of this last technique is that it also avoids well the postoperative pain commonly associated with the thoracotomy in incision. A disadvantage of this technique is that it does require that the middle portion of the esophagus be resected “blindly” and this does, on occasion, prove technically challenging. We do not suggest this approach for middle and even less so for upper third esophageal cancers. Our operative approach for the transhiatal esophagogastrectomy is described.

Fig. 4.3 The patient is suitably positioned on the left side for a right posterolateral thoracotomy in the sixth intercostal space. The patient is here in a semi-lateral position allowing both abdominal and thoracic exposure and approach.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree