RHYTHMS IN GLUCOSE REGULATION

Part of “CHAPTER 6 – ENDOCRINE RHYTHMS“

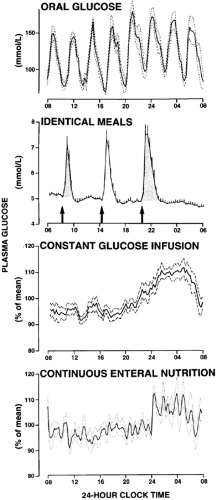

In normal humans, glucose tolerance varies with the time of day.67 Figure 6-11 illustrates circadian variations in glucose tolerance to oral glucose, identical meals, constant glucose infusion, and enteral nutrition in normal subjects. Plasma glucose responses to oral glucose, intravenous glucose, or meals are markedly higher in the evening than in the morning. Overnight studies of subjects sleeping in the laboratory have consistently observed that despite the prolonged fasting condition,

glucose levels remain stable or fall only minimally across the night, contrasting with the clear decrease that is associated with daytime fasting. Thus, a number of mechanisms operative during nocturnal sleep must intervene to maintain stable glucose levels during the overnight fast. Experimental protocols using intravenous glucose infusion or enteral nutrition (the two experimental conditions allowing for the study of nighttime glucose tolerance during sleep without awakening the subjects) have shown that glucose tolerance deteriorates further as the evening progresses, reaches a minimum around midsleep, and then improves to return to morning levels (see Fig. 6-11).67 There is evidence to indicate that this diurnal variation in glucose tolerance is partly driven by the wide and highly reproducible 24-hour rhythm of circulating levels of cortisol, an important counterregulatory hormone.68 Diminished insulin sensitivity and decreased insulin secretion in relation to elevated glucose levels are both involved in causing reduced glucose tolerance later in the day. During the first part of the night, decreased glucose tolerance is due to decreased glucose utilization both by peripheral tissues (relaxed muscles and rapid insulin-like effects of sleep-onset GH secretion) and by the brain (imaging studies have demonstrated a reduction in glucose uptake during SW sleep). During the second part of the night, these effects subside, as sleep becomes more shallow and fragmented. Thus, complex interactions of circadian and sleep effects result in a consistent and predictable pattern of changes of the setpoint of glucose regulation over the 24-hour cycle.

glucose levels remain stable or fall only minimally across the night, contrasting with the clear decrease that is associated with daytime fasting. Thus, a number of mechanisms operative during nocturnal sleep must intervene to maintain stable glucose levels during the overnight fast. Experimental protocols using intravenous glucose infusion or enteral nutrition (the two experimental conditions allowing for the study of nighttime glucose tolerance during sleep without awakening the subjects) have shown that glucose tolerance deteriorates further as the evening progresses, reaches a minimum around midsleep, and then improves to return to morning levels (see Fig. 6-11).67 There is evidence to indicate that this diurnal variation in glucose tolerance is partly driven by the wide and highly reproducible 24-hour rhythm of circulating levels of cortisol, an important counterregulatory hormone.68 Diminished insulin sensitivity and decreased insulin secretion in relation to elevated glucose levels are both involved in causing reduced glucose tolerance later in the day. During the first part of the night, decreased glucose tolerance is due to decreased glucose utilization both by peripheral tissues (relaxed muscles and rapid insulin-like effects of sleep-onset GH secretion) and by the brain (imaging studies have demonstrated a reduction in glucose uptake during SW sleep). During the second part of the night, these effects subside, as sleep becomes more shallow and fragmented. Thus, complex interactions of circadian and sleep effects result in a consistent and predictable pattern of changes of the setpoint of glucose regulation over the 24-hour cycle.

FIGURE 6-11. Twenty-four-hour pattern of blood glucose changes in response to oral glucose (top panel; 50 g glucose every 3 hours), identical meals, constant glucose, and continuous enteral nutrition in normal young adults. At each time point, the mean glucose level is shown with the standard error of the mean. (Reproduced from Van Cauter E, Polon-sky KS, Scheen AJ. Roles of circadian rhythmicity and sleep in human glucose regulation. Endocr Rev 1997; 18:716.)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|