Treatment |

Pathophysiology |

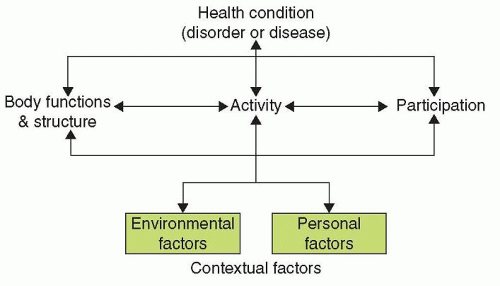

Impairment |

Disability |

Qualifiers |

Surgical resection (posterior fossa surgery) |

Unclear |

Deficits dependent on location and extent of surgery, age, and tumor type.

Cerebellar mutism; may see high-level linguistic and cognitive deficits. |

Functional limitations related to areas of deficit.

Limited verbal communication, may affect social skills and school performance. |

|

Cranial irradiation |

Neural/glial degeneration Gliosis

Proliferative/sclerosing angiopathy

Demyelination

Ischemic events related to cerebral vasculopathy

Progressive, necrotizing leukoencephalopathy.

Negative impact on GHRH when posterior fossa is involved. |

Cognitive dysfunction learning disabilities

↓ memory attention problems language deficits

↓ executive function

↓ verbal and performance IQ

Short stature |

↓ academic potential

↓ communication skills to language disorder/delay may impact behavior, social competence, and vocational potential.

Functional deficits related to location and extent of ischemia.

Potential for marked functional impairments in all affected areas, including dementia, dysarthria, ataxia and/or spasticity.

May affect self-image, social competence. |

Impact related to dose and volume of CNS irradiated and inversely related to age of child at time of exposure. Effects potentiated by IT or high-dose intravenous methotrexate.

Rehabilitation managed as in stroke.

Usually seen when treatment has included methotrexate.

Cosmesis included in problem list for adolescents. |

Spinal irradiation |

May cause radiation myelitis

Failure of vertebral growth |

Spastic quadriplegia or paraplegia

Neurogenic bowel and bladder

Short stature, ↑ risk of scoliosis or kyphosis |

Functional impairments in mobility and ADLs dependent on level of injury

May require special program for evacuation of bladder and bowel

Potential altered self-image and ↓ social competence |

Management as in spinal cord injury

Cosmesis of particular psychosocial impact for adolescents |

Mediastinal irradiation |

Vascular damage, fibrosis

In very young, possible interference with both lung and chest wall growth.

Fibrosis of the parietal pericardium (most common), intimal proliferation of myofibroblasts, collagen and lipid accumulation. |

Pulmonary fibrosis

Pneumonitis

Decreases in lung volume, compliance, and CO diffusing capacity.

Constrictive pericarditis, myocardial damage (rare), conduction system defects, coronary artery disease. |

Disability dependent on degree of restrictive lung changes and can significantly limit ADLs, exercise tolerance when severe.

Functional limitations related to degree of cardiac dysfunction. |

Decrease in radiation-induced late pulmonary toxicity seen over last decade due to refinements in radiation therapy. |

Methotrexate |

Neurotoxicity including acute, stroke-like encephalopathy, chronic leukoencephalopathy (progressive demyelinating encephalopathy)

Osteopathy. |

Cognitive impairment, developmental delay, learning problems, potential motor impairment with deficits in coordination and high-level skills.

With intrathecal dosing, can see ascending radiculopathy, similar to GBS.

Osteoporosis/ ↑ risk of pathologic fractures, bone pain |

May affect school performance, ↓ age-appropriate ADL, independence, may limit participation in athletics, team sports, impact self-esteem and social competence.

Loss of motor function with consequent mobility and ADL deficits dependent on extent of weakness.

Limitations in mobility and ADLs related to areas involved. |

Neurotoxicity potentiated by cranial irradiation.

Alert parents to monitor for school problems developing in upper grades when ↑ independence and efficiency required.

Toxicity cumulative |

Corticosteroids |

Preferential atrophy of type II muscle fibers. |

Myopathy

Osteoporosis

Avascular necrosis

Growth failure |

Decreased mobility related to proximal muscle weakness

↑ risk of pathologic fracture

Hip pain, gait abnormality

Impacts self-esteem and social competence. |

Reversible when drug withdrawn or dose reduced

↑ risk for osteonecrosis of weight-bearing joints in children when ↑ doses used. |

Vincristine/Vinblastine |

Axonal sensorimotor polyneuropathy.

Impairment of efferent and afferent pathways from the sacral spinal cord, autonomic neuropathy. |

Impaired rectal emptying |

Paresthesias, neuritic pain, distal weakness which may impair hand function, cause foot drop and walking difficulty.

Constipation which may alter ADLs, comfort. |

Neurotoxicity more prominent in presence of CMT.

Usually recovers with end of therapy or ↓ dose.

Neurotoxicity usually minimal with vinblastine. |

Anthracycline (doxorubicin, daunorubicin) |

|

Can cause arrhythmias, conduction abnormalities, ↓ left ventricular function, chronic cardiomyopathy |

Diminished capacity to perform age-appropriate ADLs, ↓ endurance, ↓ exercise tolerance, limited ability to participate in sports, may impact self-esteem and social competence. |

Potentiates radiation reactions.

Increased toxicity with lower age. |

Cisplatin |

Injury to hair cells of the organ of Corti |

High-frequency sensorineural hearing loss.

Tinnitus

Reversible sensory peripheral neuropathy. |

Affects communication skills and potentially speech/language development in the young child; may impact social competence.

Paresthesias/neuritic pain may interfere with ADLs, comfort. |

Ototoxic and neurotoxic effects are cumulative.

Symptoms may progress after discontinuation. |

Carboplatin |

Minor or absent loss of hair cells of the organ of Corti. |

High-frequency sensorineural hearing loss |

Affects communication skills and potentially speech/language development in the young child; may impact social competence. |

Effects are cumulative

Ototoxicity and neurotoxicity milder than cisplatin |

Cyclophosphamide/Ifosfamide |

Can cause hemorrhagic cystitis secondary to urotoxic metabolite acrolein. |

Reversible neurotoxicity with somnolence, disorientation, lethargy, hallucinations

Avascular necrosis

Potential loss of renal function. |

Negative impact on ability to perform age-appropriate ADLs.

Pain may limit ADLs, ambulation. |

Reversible or preventable with methylene blue.

Risk of neurotoxicity ↑ with prior use of high-dose cisplatin.

Occurrence decreased by use of MESNA. |

GHRH, growth hormone-releasing hormone; IT, intrathecal; ADLs, activities of daily living; GBS, Guillain-Barrè syndrome; CMT, Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease; MESNA, sodium 2-mercaptoethanesulfonate. |