TABLE 37.1 Esthesioneuroblastoma—Hyams Histopathologic Grading System | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||

TABLE 37.2 Esthesioneuroblastoma—Modified Kadish Staging System | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||

with oropharyngeal cancer regardless of the use of tobacco or alcohol. The incidence of HPV-associated oropharyngeal cancer has significantly increased since 1973, particularly among white males aged 40 to 59 years.31 Approximately 20% to 25% cases of head and neck cancer contain oncogenic HPV, mostly types 16, 31, and 33. In a study of 1,235 children, the prevalence of HPV in the oral cavity was 1.9% and the highest rates were seen in patients younger than 1 year and in those aged between 16 and 20 years.32 HPV-associated oral cancers tend to occur in younger patients of high socioeconomic status, are associated with sexual behavior, more often involve the lingual and palatine tonsils, frequently have poorly differentiated basaloid features, express p16, and have a better prognosis and response to radiotherapy than other head and neck carcinomas.33,34,35 Current preventive strategies that incorporate vaccine programs targeting the adolescent population may prove beneficial in decreasing the incidence of cervical and head and neck HPV-associated cancers.36,37

million per year.57 Although representing approximately 1% of all pediatric malignancies, it accounts for 35% to 50% of all nasopharyngeal malignancies. NPC originates from the surface epithelium and differs from other head and neck carcinomas by its very distinct histologic, epidemiologic, and biologic characteristics. NPC has an endemic distribution among well-defined ethnic groups, such as inhabitants of some areas of Southeast Asia and in Alaskan Eskimos, where the incidence is 25 to 50 and 15 to 20/100,000 persons per year, respectively.58

cells containing the virus. Staging of NPC usually follows the TNM system, which has been shown to be predictive of outcome, and very helpful in defining therapy (Table 37.3).64

TABLE 37.3 AJCC Staging System for Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

durable responses, and patients with EBV+ recurrent NPC should be considered for this type of therapy in combination with a taxane-containing salvage regimen.69

TABLE 37.4 Treatment of Advanced Childhood Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

mass, malocclusion, paresthesias, pain, and evidence of unerupted teeth in the affected area.73,75 Analysis of small numbers of tumors suggest that p53, MDM2, and p14 may be responsible for tissue structuring and cytodifferentiation in ameloblastoma.74 In addition, recent reports have documented the existence of a complex interaction that favors tumor formation and is mediated by the secretion of frizzled-related peptide (sFRP2), which impairs bone formation, as well as IL-6 and RANKL, which promote bone resorption.76,77

recurrent pneumonia, or hemoptysis and mediastinal and distant metastases are often present at diagnosis.113,116 Treatment recommendations for children with lung carcinomas should be made in consultation with adult oncologists who are experienced in treating these histologies.

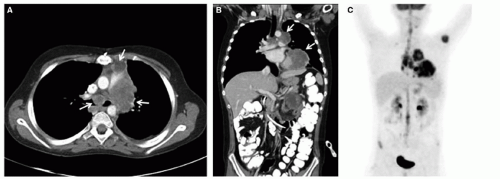

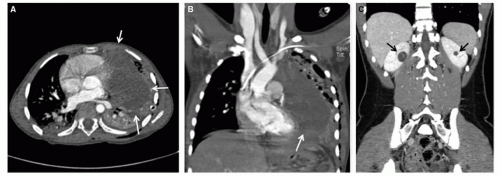

Figure 37.5 DICER1 syndrome. A and B: Six-year-old girl presenting with chest pain and respiratory distress. Family history was significant for thyroid nodules in the father, who underwent thyroidectomy during adolescence. Axial (A) and coronal (B) CT images demonstrate a large left Type III pleuropulmonary blastoma (white arrows). C: Sixteen-year-old female with history of vaginal/cervical rhabdomyosarcoma at 4 years of age. Coronal CT shows bilateral hypoattenuating cystic masses with enhancing septations (black arrows). Partial nephrectomies revealed cystic nephroma. Both patients tested positive for germ-line DICER1 mutations.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|