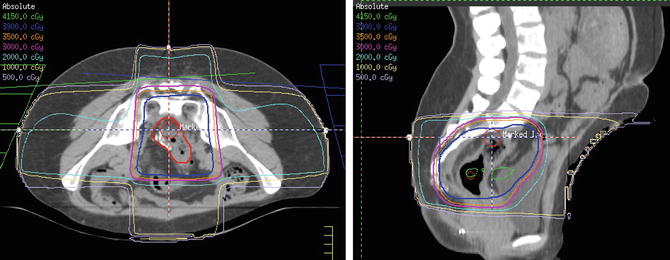

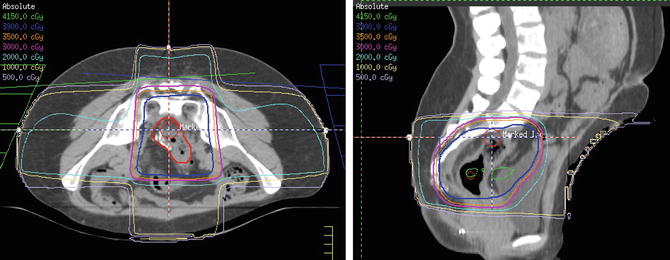

Fig. 5.1

3D conformal radiation therapy treatment plan for preoperative chemoradiation in a man with T3N1 distal rectal adenocarcinoma. The patient was treated using a prone belly board technique, with a dose of 45 Gy (blue), followed by a boost to the rectal tumor and adjacent high-risk areas with a cumulative dose of 50.4 Gy (white)

The National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project R-03 trial also provides support for the use of preoperative chemoradiation [7]. In this trial , patients were randomized to either preoperative or postoperative chemoradiation, with a radiation dose of 50.4 Gy. Patients in both arms received a cycle of bolus fluorouracil and leucovorin before radiation, two cycles with radiation, and four additional adjuvant cycles. This trial was underpowered since it was not able to meet its accrual goals and enrolled only 267 out of a planned 900 patients. Unlike in the German trial, there was no significant difference in local control or toxicity between the two arms. However, there was a significant improvement in disease-free survival (65 vs. 53%, P = 0.011) and a trend toward improvement in overall survival (75 vs. 66%, P = 0.065) in patients in the preoperative arm, compared to the postoperative arm. The specific results of this trial should be interpreted cautiously, given its limited accrual. However, this trial does provide general support to the preoperative approach.

A potential downside of preoperative treatment is the possible overtreatment of some patients. Since pretreatment staging may not be completely accurate, some patients may be overstaged and given unnecessary preoperative treatment. For example, in the German rectal cancer trial, 18% of patients in the postoperative arm were found to have stage I disease at surgery instead of stage II–III disease and were, therefore, not administered postoperative treatment [5]. This indicates that around 18% of patients in the preoperative arm likely had stage I disease and were overtreated with preoperative chemoradiation. Hopefully, improvements in staging methods with time will decrease the proportion of overstaged patients, thereby reducing the inappropriate use of preoperative therapy.

Two randomized trials have compared preoperative chemoradiation and preoperative long course radiation for rectal cancer. In the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) 22,921 trial , 1011 patients were randomized to preoperative chemoradiation or radiation and also to adjuvant chemotherapy or no chemotherapy [8, 9]. Patients treated with preoperative chemoradiation had a higher rate of pathologic complete response (14 vs. 5%), smaller tumors, and less advanced T and N stages on surgical pathology, compared to those treated with preoperative radiotherapy alone. Furthermore, those treated with radiation and concurrent and/or adjuvant chemotherapy had significantly lower rates of local recurrence compared to those treated with radiation and no chemotherapy (8–10 vs. 17%, P = 0.002). Similarly, in the Federation Francophone de Cancerologie Digestive (FFCD) trial, 762 patients were randomized to receive either preoperative radiation or preoperative chemoradiation [10]. Patients treated with preoperative chemoradiation had significantly higher rates of pathologic complete response (11 vs. 4%) and significantly lower rates of local recurrence (17 vs. 8%, P < 0.05). Hence, preoperative chemoradiation has been shown to have increased efficacy, with somewhat increased toxicity, compared to preoperative long course radiotherapy alone.

The German trial, along with the other trials discussed above, has established preoperative chemoradiation as a standard of care for patients with stage II and III rectal cancer (Table 5.1). Preoperative chemoradiation has been rapidly and widely adopted in clinical practice, following publication of these results. For instance, a study based on the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) tumor registry showed that the use of preoperative radiation therapy increased from 33% in 2000 to 64% in 2006, among those treated with radiation therapy [11]. Multiple trials have evaluated different concurrent chemotherapy regimens for preoperative treatment; these trials have been discussed elsewhere in this textbook.

Table 5.1

Randomized trials on preoperative chemoradiation for rectal cancer

Trial/arms | N | Pathologic complete response (%) | 5-year local recurrence (%) | ≥ Grade 3 acute toxicity (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

823 | ||||

Preop chemoradiation | 8 | 6 | 27 | |

Postop chemoradiation | NA | 13 | 40 | |

NSABP R-03 [7] | 267 | |||

Preop chemoradiation | 15 | 11 | 41 | |

Postop chemoradiation | NA | 11 | 49 | |

1011 | ||||

Preop radiation | 5a | 17 | 7a,b | |

Preop radiation + postop chemo | 10 | |||

Preop chemoradiation | 14a | 9 | 14a,b | |

Preop chemoradiation + postop chemo | 8 | |||

FFCD [10] | 762 | |||

Preop radiation | 4 | 17 | 3b | |

Preop chemoradiation | 11 | 8 | 15b |

Short Course Radiotherapy

Short course radiotherapy , consisting of five treatments of 5 Gy each in a single week, has long been established as another standard of care for rectal cancer (Table 5.2). A landmark trial on this treatment approach was the Swedish Rectal Cancer Trial , in which 1168 patients were randomized to undergo either surgery or preoperative short course radiotherapy followed by surgery [12]. Long-term results from the trial with a 13-year median follow-up show persistent and statistically significant improvements in overall survival (38 vs. 30%, P = 0.008), cancer-specific survival (72 vs. 62%, P = 0.03), and local recurrence (9 vs. 26%, P < 0.001) in the preoperative radiotherapy arm, compared to the surgery alone arm [13].

While the Swedish Rectal Cancer Trial was conducted in an era prior to the advent of total mesorectal excision, subsequent randomized trials have evaluated the role of short course radiotherapy in patients treated with total mesorectal excision. In the Dutch Colorectal Cancer Group trial , 1861 patients were randomized to undergo either total mesorectal excision or short course radiotherapy followed by total mesorectal excision [14, 15]. In this trial, short course radiotherapy reduced local recurrences by over 50% compared to the surgery alone group (10-year rate 5 vs. 11%, P < 0.0001). While overall survival was not significantly different between the two arms of the entire trial, overall survival was improved with radiotherapy in stage III patients that underwent surgery with negative circumferential resection margin.

Preoperative short course radiotherapy was also evaluated in the Medical Research Council (MRC) CR07/National Cancer Institute of Canada (NCIC) C016 trial [16]. In this trial, 1350 patients were randomized to either short course radiotherapy followed by surgery or initial surgery followed by selective postoperative chemoradiation. Selective postoperative chemoradiation consisted of 45 Gy with concurrent fluorouracil and was administered only to patients with positive circumferential resection margin, who comprised only 12% of patients in that arm. Patients in the preoperative short course radiotherapy arm had significantly lower rates of local recurrence (3-year rates 4 vs. 11%, P < 0.0001) and significantly higher rates of disease-free survival (3-year rates 78 vs. 72%, P = 0.013). Importantly, the benefit from preoperative radiotherapy did not seem to differ depending on the plane of surgery (mesorectal or intramesorectal or muscularis propria plane) [17]. The combination of preoperative radiotherapy and surgery in the mesorectal plane appeared to yield the best local control, with a 3-year local recurrence rate of just 1%. Thus, the Dutch and MRC/NCIC trials both support the use of preoperative short course radiation therapy in patients undergoing total mesorectal excision.

The use of short course radiotherapy varies between countries, ranging from widespread use in selected European countries to relatively low rates of adoption in North America. Based on radiobiology principles, some radiation oncologists have expressed concerns that the large fraction size of radiotherapy in short course could potentially lead to high rates of long-term toxicity. Data from the Dutch and MRC/NCIC trials do provide some support for such concerns. Long-term quality of life questionnaires among patients in the Dutch trial showed increased fecal leakage rate, stool frequency, and erectile problems among patients in the preoperative radiotherapy arm compared to the surgery alone arm [18]. Similarly, quality of life questionnaires from the MRC/NCIC trial showed higher rates of male sexual dysfunction and fecal incontinence in the preoperative radiotherapy arm [19].

Short course radiotherapy and long course chemoradiation may both be considered standard of care for the preoperative treatment of rectal cancer. Randomized trials have compared these two approaches (Table 5.3). In a trial from Poland, 316 patients were randomized to either short course radiotherapy (5 Gy × 5), followed by surgery in a week, or long course radiotherapy (50.4 Gy) with concurrent fluorouracil and leucovorin, followed by surgery after four to 6 weeks [20]. Patients in the long course chemoradiation arm showed higher rates of pathologic complete response (16 vs. 0.7%) and lower rates of positive circumferential resection margin (4 vs. 13%, P = 0.017). The 4-year rate of local recurrence was 10.6% in the long course chemoradiation group and 15.6% in the short course group (P = 0.21). There was no significant difference in sphincter preservation, disease-free survival, or overall survival between the two groups. There was also no difference in the rate of severe late toxicity between the two groups. In the Trans-Tasman Radiation Oncology Group (TROG) trial 01.04, 326 patients were randomized to short course radiotherapy (5 Gy × 5), followed by surgery in a week, or long course radiotherapy (50.4 Gy) with concurrent infusional fluorouracil, followed by surgery in four to 6 weeks, with both groups receiving adjuvant fluorouracil and leucovorin [21]. Patients in the long course group showed significantly higher rates of pathologic downstaging (45 vs. 28%, P = 0.002) and pathologic complete response (15 vs. 1%). The 3-year local recurrence rate was 7.5% in the short course group and 4.4% in the long course group (P = 0.24). There was no significant difference in the rates of sphincter preservation, distant recurrence, or overall survival between the two groups, nor was there a significant difference in the rate of grade 3–4 late toxicity between the two groups. Although the Polish and TROG trials did not show a significant difference in local recurrence rates between the long course and short course groups, these trials were relatively small and may have been underpowered to detect a small but clinically relevant difference in local control. The local recurrence rates do appear to be numerically 3–5% higher in the short course groups, whereas the TROG trial was designed to detect a 10% difference in local recurrence. Furthermore, while the Polish and TROG trials did not show any differences in late toxicity, much longer follow-up would be needed to fully evaluate the impact of radiotherapy on long-term bowel and sexual function, as suggested by the quality of life studies from the Dutch and MRC/NCIC trials discussed above. Finally, in both the Polish and TROG trials, long course radiotherapy was associated with enhanced pathologic response, but this may have arisen partly from the longer interval between radiotherapy and surgery in the long course arms of these studies. Combining short course radiotherapy with delayed surgery could potentially enhance pathologic response [22, 23]. The Stockholm III trial is currently comparing short course radiotherapy with surgery in 1 week, short course radiotherapy with surgery in 4–8 weeks, and long course radiotherapy with surgery in 4–8 weeks [24]. Results from this trial will further add to our understanding of the role of short course radiotherapy for rectal cancer.

Table 5.3

Randomized trials comparing short course radiotherapy and long course chemoradiation

Trial/arms | N | Pathologic complete response (%) | Local recurrence (%) | Severe late toxicity (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Polish [20] | 312 | |||

Preop short course | 1 | 15.6 | 10 | |

Preop chemoradiation (long course) | 16 | 10.6 | 7 | |

TROG [21] | 326 | |||

Preop short course | 1 | 7.5 | 6 | |

Preop chemoradiation (long course) | 15 | 4.4 | 8 |

Radiotherapy for Watch and Wait and Local Excision Approaches

Since chemoradiation can lead to pathologic complete responses in a proportion of patients, selected patients could potentially be treated with chemoradiation and local excision, or even chemoradiation alone. The strategy of trying to avoid surgery altogether has been termed the watch and wait approach . Avoiding surgery could potentially lead to better functional outcomes and better quality of life. The largest systematic study on this approach was from Brazil [25, 26]. In this study, 361 patients were treated with radiation therapy (50.4 Gy) and concurrent fluorouracil and leucovorin; 122 patients attained clinical complete response and 99 (27%) had sustained complete regression for at least 1 year. Patients were required to have no residual mass or ulcer on clinical evaluation and endoscopy, as well as no residual tumor on imaging studies, to be considered to have clinical complete response. Of the 99 patients with sustained complete regression, only 5% developed endoluminal recurrences, none developed pelvic regional recurrence, and 8% developed metastatic disease. Of the five patients that developed endoluminal recurrences, three underwent salvage abdominoperineal or low anterior resections, while two refused radical surgery and underwent local excision or brachytherapy. The 5-year rates of overall and disease-free survival were 93% and 85%, respectively. This study suggests that watch and wait could be a reasonable option in carefully selected and closely followed patients.

In a prospective Dutch trial, 192 patients were treated with radiation therapy (50.4 Gy) with concurrent capecitabine, of whom 21 (11%) attained clinical complete response [27]. Response was assessed based on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and endoscopy, and patients were followed closely with MRI, endoscopy, digital rectal examination, and carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) levels. At a mean follow-up of about 2 years, only 1 of the 21 patients had an endoluminal recurrence. The 2-year rates of overall and disease-free survival were 100% and 89%, respectively. In contrast, some prospective and retrospective studies have reported high rates of local recurrence, ranging from 20 to 80%, with the watch and wait approach [28–31].

Many questions remain unanswered about the watch and wait approach , such as the optimal methods for assessing response to chemoradiation, the optimal methods and timing for follow-up evaluations, and the long-term functional outcomes and quality of life associated with this treatment. Patients treated with watch and wait need to be followed systematically and closely, since many of these patients may develop local recurrences that need salvage surgery. The wide range in local recurrence rates between studies raises some concerns about the efficacy of this approach. Additional prospective studies with adequate follow-up will be needed before this approach can be accepted as a standard.

Preoperative chemoradiation could also be used in combination with local excision for selected patients. A number of retrospective studies have shown excellent local control rates in patients treated with preoperative chemoradiation and local excision [32–34] (Table 5.4). These studies primarily evaluated patients that were not candidates for radical excision or patients that declined radical excision. A retrospective study from MD Anderson reported outcomes in 47 patients with T3 rectal cancer treated with preoperative radiation (45–52.5 Gy) with concurrent fluorouracil [32]. Of these patients, 49% had pathologic complete response and 36% had microscopic residual disease after chemoradiation. The 10-year actuarial risk of local recurrence was 10.6% in these patients, in comparison to a rate of 7.6% in a cohort of 473 patients treated with total mesorectal excision at the same institution. Similarly, a retrospective study from Korea showed 89% 5-year local relapse-free survival in 27 patients with mostly T3 rectal cancer that were treated with preoperative chemoradiation and local excision [33]. Another retrospective study reported outcomes in 44 patients with T2–T3 rectal cancer treated with preoperative chemoradiation and local excision [34]. Pathologic complete responses were seen in 43% of patients. Only two patients developed isolated local recurrences, and two developed local and distant recurrences. The results of these studies should be interpreted cautiously given their retrospective nature. Careful selection of patients likely contributed to these results, as suggested by the high proportion of patients with pathologic complete responses in some of these studies.

Table 5.4

Selected studies on watch and wait and local excision

Study | Treatment | N | Results |

|---|---|---|---|

Radiation + watch and wait | 99 | 5% endoluminal recurrence, 85% 5-year DFS | |

Dutch [27] | Radiation + watch and wait | 21 | 89% 2-year DFS |

MD Anderson [32] | Radiation + local excision | 47 | 49% pCR, 10.6% 10-year local recurrence |

ACOSOG Z6041 [35] | Radiation + local excision | 77 | 44% pCR |

A recent phase II prospective trial has investigated the combination of preoperative chemoradiation and local excision for T2N0 patients [35]. In the American College of Surgeons Oncology Group (ACOSOG) Z6041 trial, patients with clinical T2N0 rectal cancer were treated with preoperative radiation therapy with a dose of 54 Gy, along with concurrent capecitabine and oxaliplatin, followed by local excision. Of 77 eligible patients that completed protocol-based chemoradiation and local excision, 44% had pathologic complete response and 99% had negative margins. However, the rate of grade 3 or higher complications was relatively high (39%) with this regimen. Information on local recurrence and disease-free survival is not yet available from this study.

Based on the studies discussed above, at this time, the combination of preoperative chemoradiation and local excision for T3 patients appears appropriate mainly for patients that are medically unfit for radical surgery or patients that refuse radical surgery, though good oncologic outcomes have been reported for selected patients in multiple retrospective studies. Preoperative chemoradiation and local excision could be a potential treatment option for T2N0 patients; however, long-term oncologic outcomes will be needed from the ACOSOG Z6041 trial to support this approach.

Selective Use of Radiotherapy

There exists considerable variation among rectal cancer patients in their risk for local recurrence and, therefore, in the magnitude of their benefit from radiation therapy. While the randomized trials on preoperative and postoperative chemoradiation discussed above typically included all stage II and III patients , certain patient subgroups have relatively low risk of local recurrence and could potentially be treated without radiation therapy, thereby sparing them from the acute and late side effects of radiation therapy.

A pooled analysis of 3791 patients from five randomized trials evaluated survival and relapse rates in patient subgroups, based on T and N classification [36]. This study identified an intermediate-risk group of patients, with stages T1-2N1 and T3N0. Patients in the intermediate-risk group had 5-year local relapse rates of 12–14% with surgery alone, 5–11% with surgery and chemotherapy, and 5–10% with surgery and chemoradiation. While this was a pooled analysis and not a planned prospective or randomized comparison between these treatment approaches, the data from this study suggests that certain patients may have low risk of local recurrence without radiation therapy, especially if they receive chemotherapy.

A prospective European trial, called the MERCURY study , evaluated the role of MRI in identifying patients at low risk of local recurrence who could be treated with surgery without radiation therapy [37]. MRI was used to identify good prognosis patients, based on the following imaging criteria: safe circumferential resection margin with tumor >1 mm from the mesorectal fascia; no extramural venous invasion; stages T2, T3a, and T3b, i.e., extramural spread <5 mm; and no encroachment into intersphincteric plane or levators for low rectal tumors. Among 374 patients in the MERCURY study, 122 (33%) met the good prognosis criteria and were treated with surgery alone. Patients in the good prognosis group had only 3% local recurrence rate. Moreover, the 5-year rates of disease-free survival and overall survival in this group were 85% and 68%, respectively. The MERCURY study suggests that MRI can be used to select patients that can be treated without radiation therapy. The success of this approach depends on the availability of good-quality MRI and appropriate interpretation of the images by highly trained radiologists. In certain regions such as the United Kingdom, MRI-based selective use of radiotherapy has now been accepted as a standard of care.

A small prospective trial at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center investigated the use of preoperative chemotherapy without radiation therapy for rectal cancer [38]. In this trial, 32 patients with stage II–III rectal cancer who were candidates for low anterior resection underwent preoperative chemotherapy with FOLFOX (fluorouracil, leucovorin, and oxaliplatin) and bevacizumab. Two patients were not able to complete chemotherapy and received preoperative chemoradiation. All patients underwent R0 resection. The pathologic complete response rate to chemotherapy was 25%. The 4-year rates of local recurrence and disease-free survival were 0 and 84%. This trial suggests that preoperative chemotherapy could be a potential alternative to preoperative chemoradiation for selected patients. It should be noted this was a relatively small, single-institution trial, and patient selection may have contributed to these results. A large phase II/III randomized multi-institutional trial is currently underway to further study the role of preoperative chemotherapy as an alternative to preoperative chemoradiation. In the Preoperative Radiation or Selective Preoperative Radiation and Evaluation Before Chemotherapy and TME (PROSPECT) trial , patients with T2N1, T3N0, and T3N1 rectal cancer with distal edge 5–12 cm from the anal verge are being randomized to either routine preoperative chemoradiation or preoperative chemotherapy with FOLFOX, along with selective chemoradiation. In a few years, results from the PROSPECT trial may help us better understand whether radiation therapy can be used more selectively in rectal cancer patients.

Reirradiation

Traditionally, only one course of pelvic radiation therapy was administered to rectal cancer patients, because of the potential risk of toxicity with reirradiation . However, even after preoperative chemoradiation or short course radiotherapy and surgery, rectal cancer patients have 5–10% risk of local recurrence [6, 8, 10]. Reirradiation could play a role for palliation or definitive salvage therapy in these patients, albeit at a higher risk of toxicity (Fig. 5.2).

Fig. 5.2

3D conformal radiation therapy treatment plan for preoperative reirradiation in a woman with an anastomotic recurrence of rectal adenocarcinoma. The patient was previously treated with a dose of 50.4 Gy 3 years ago and was given reirradiation with a dose of 39 Gy (blue) in 1.5 Gy twice-daily fractions

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree