Variability exists in the quality of pancreatic cancer care provided in the United States. High-volume centers have been shown to have improved outcomes for pancreatectomy. Regionalization of pancreatic cancer care to high-volume centers has the potential to improve care and outcomes. Practical limitations such as overloading currently available high-volume centers, extending patient travel times, sharing patients within a multipayer health system, and incorporating patient preferences must be addressed for regionalization to become a reality. The benefits and limitations of regionalization of pancreatic cancer care are discussed in this review. To improve the overall quality of pancreatic cancer care at all hospitals in the United States, a combination of referral of patients with pancreatic cancer to high- and moderate-volume hospitals in conjunction with specific quality-improvement efforts at those institutions is proposed.

The Institute of Medicine released a report in 1999 entitled Ensuring Quality Cancer Care that documented considerable discrepancy between ideal and observed cancer care in the United States. In examining care for more than 30 acute and chronic conditions, McGlynn and colleagues found that just more than half of patients in the United States receive medical care consistent with established recommendations. Similar variation in the delivery of cancer care has been demonstrated across several specific cancer types. To better understand the observed discrepancy in the delivery of high-quality care, health-outcomes researchers have studied the volume-outcome relationship. The general concept is that the higher the volume of health services provided by hospitals or individual physicians, the better the patient outcomes.

In 2002, a systematic review of 135 studies examining the volume-outcome association found that 70% of the studies, across a wide variety of surgical procedures, showed a statistically significant association between higher volume and lower mortality. None of the studies documented in this meta-analysis showed an association between higher case volume and poorer outcomes. It has been estimated that hundreds of deaths could be prevented in the United States if elective high-risk surgery were to be performed exclusively at high-volume hospitals. Defining patients or procedures as high risk and determining a specific number of cases as a high-volume threshold is difficult. Patient characteristics such as health status and comorbidities vary between those who receive care at low-volume hospitals and those who receive care at high-volume hospitals. Studies comparing the annual volume of procedures often have overlapping volume thresholds, in which the definition of high volume used in one study is considered low volume in another study. The effect of procedure-specific complexity and provider factors on the volume-outcome association has been more difficult to decipher. Underlying factors explaining the volume-outcome relationship have remained undefined. Although it is generally accepted that volume is a crude proxy for quality, there are few alternative options to explain differences in quality at the hospital level. Volume is easy to measure and is clearly associated with outcomes, and thus insurance companies and oversight agencies have accepted procedure volume as the best currently available measure of quality.

The volume-outcome correlation is generally most noticeable when a rare high-risk condition is encountered, as is the scenario in dealing with complex surgical procedures. Several specific cancer-related surgical procedures have been identified and targeted for volume-based referral including pulmonary resection, esophagectomy, and pancreatectomy. Regionalization efforts and research have focused on pancreatectomy because of demonstrated decreased mean length of stay, costs, delayed gastric emptying, pancreatic anastomotic leaks or fistulas, intra-abdominal abscesses, hemorrhage, perioperative mortality, and long-term survival.

Some have suggested moving all complex surgical care, such as pancreatectomy, to high-volume specialized centers to improve outcomes. Moreover, payers, purchasers, and government oversight agencies have acknowledged the improved outcomes associated with the volume-outcome relationship and are already enacting volume-based referral. Although this may seem to be an effective approach to improving quality, considerable issues exist surrounding volume-based referral for pancreatectomy. This review contrasts the benefits and limitations of regionalizing pancreatic cancer care.

Argument in favor of regionalization

Regionalization is a term used to describe shifting a set of procedures to certain hospitals (eg, high-volume) to improve surgical outcomes. Procedure volume is easy to acquire from administrative data for individual hospitals and surgeons. Perhaps the best example of regionalization of a surgical procedure in the last 3 decades is observed in coronary artery bypass surgery in New York, where 60% of all operations take place at hospitals performing 500 or more surgeries per year. Nevertheless, several studies have shown that the benefits of selective referral and regionalization may have the largest effect on rare conditions, such as pancreatic cancer.

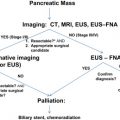

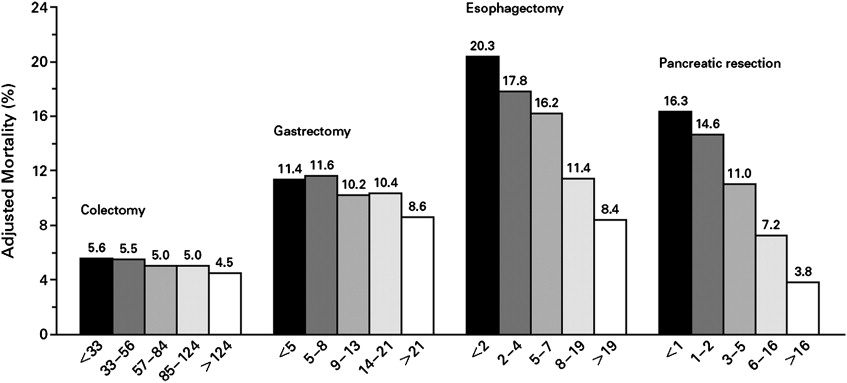

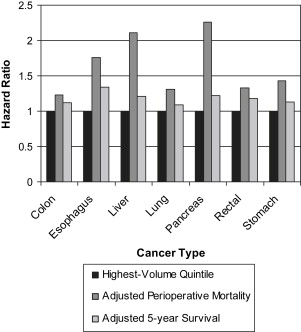

The volume-outcome relationship has a dramatic effect on outcomes in pancreatic surgery. Compared with high-volume centers, low-volume centers have a higher likelihood (4- to 5-fold) of perioperative mortality ( Fig. 1 ). This increased mortality associated with low-volume centers has been confirmed by various studies using statewide registry data from Maryland, California, Texas, and New York, and national registry data from the Netherlands, Italy, and Belgium. Several large observational studies of patients in the United States have also been conducted. An assessment of 7229 Medicare patients undergoing pancreaticoduodenectomy found that mortality was 3- to 4-fold higher at low- and very-low-volume hospitals compared with high-volume hospitals (12% and 16%, respectively vs 4%, P <.001). An evaluation of SEER (Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results) data adjusted for comorbidity, patient age, and cancer stage also demonstrated lower mortality at high-volume hospitals compared with low-volume centers for pancreatectomy (5.8% vs 12.9%, P = .004). Another study used the Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS) to evaluate 39,463 patients undergoing pancreatectomy and found centers performing fewer than 5 procedures per year had 3 times the in-hospital mortality of hospitals performing more than 18 procedures per year. This study also showed an increase in the percentage of pancreatic resections for neoplasm performed at high-volume centers from 1998 to 2003 ( P <.00001). Late survival post pancreatic resection has also been shown to be influenced by hospital volume. Using Medicare claims data, high-volume centers have been shown to have higher overall 3-year survival compared with lowest-volume centers (37% vs 25%, P <.0001). Data from the Commission on Cancer’s National Cancer Data Base (NCDB) show that lowest-volume hospitals have an increased risk of perioperative mortality and 5-year risk of death compared with the highest-volume hospitals (hazard ratio [HR] 2.26 and 1.13, P <.05, Fig. 2 ).

Length of stay post pancreatic resection has been demonstrated to be shorter at high-volume centers, translating directly into reduced costs. Gordon and colleagues showed that charges at high-volume centers were 14% less than those at low-volume centers. Procedure-specific morbidity, such as pancreatic leakage/fistula formation, intra-abdominal abscesses, and repeat laparotomies, has been shown to be lower at high-volume centers. Single surgeon reports note additional improved outcomes, including lower blood loss, less need for transfusion, and lower need for reoperation. General complications associated with pancreatectomy and other high-risk procedures, including aspiration, cardiac complications, infection, pneumonia, and renal failure have also been shown to be lower at high-volume hospitals compared with low-volume hospitals (collective odds ratio [OR] 0.71; 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.57–0.83, P = .002).

In addition to lower costs, length of stay, morbidity, and mortality, high-volume centers have been shown to offer more standardized cancer care. For example, adjuvant therapy has been shown to improve survival in patients with pancreatic cancer. Highest-volume hospitals have been shown to have higher compliance with use of adjuvant therapy (adjusted OR 1.2, 95% CI 1.1–1.3) despite evidence that adjuvant therapy improves survival. Positive margins after pancreatic cancer resection are associated with increased mortality. Patients with pancreatic cancer are more likely to have a margin positive resection at a low-volume hospital (adjusted OR 1.21, 95% CI 1.01–1.43). A key component to stage and manage pancreatic cancer accurately is appropriate nodal assessment. Patients are more likely to have a higher number of nodes evaluated at high-volume centers. From a quality-of-life standpoint, patients undergoing pancreatic surgery at high-volume hospitals are more likely to be discharged home as opposed to intermediate-care facilities. Appropriate patient selection may occur at higher-volume hospitals considering most diagnoses are made at advanced stages and surgical intervention for early-stage disease is underused at lower-volume hospitals.

Adverse outcomes are lower not only in hospitals that perform a high number of a specific procedure but also in hospitals that perform a high number of similar complex procedures. For example, Urbach and Baxter have shown that hospitals that perform a high volume of lung resections have lower association of mortality from pancreaticoduodenectomy compared with hospitals with a low-volume of lung resections (OR for death 0.36, 95% CI 0.23–0.57). The association with a high volume of lung resections was stronger than the association of mortality from pancreaticoduodenectomy with hospital volume of pancreaticoduodenectomy (OR for death 0.76, 95% CI 0.44–1.32). An evaluation of hepatopancreatobiliary surgery using the NIS showed that operations performed at a transplant center had 21% lower odds of perioperative mortality even although nontransplant surgeons performed 97% of pancreatic procedures. Historical measures of operative mortality or procedure volume at a given hospital have been shown to predict better outcomes in the future even if the procedure volume decreases. These findings point to broader hospital-level characteristics when attempting to explain the improved outcomes.

Although not fully defined, characteristics at high-volume hospitals that potentially explain improved outcomes include access to cutting-edge technology, highly trained surgeons, experienced physicians and specialists other than surgeons, dedicated nursing staff, and increased use of clinical management pathways. Joseph and colleagues have shown that high-volume centers have access to more clinical resources as a whole ( P <.001). Several key characteristics have been studied. First, high-volume centers have been shown to be more likely to use several key perioperative processes such as cardiac stress tests, medical and radiation oncology consultations, and invasive perioperative monitoring. Perioperative management, in nutritional support and pain management using locoregional techniques, has been shown to improve outcomes in pancreatic surgery patients. A higher percentage of board-certified specialists, including critical-care intensivists, has been shown to be associated with decreased mortality and improved outcomes across hospital systems and in management of postoperative pancreatic surgery patients. A calculation of lives potentially saved by implementation of intensivist staffing across intensive care units in the United States found that approximately 53,850 lives could be saved each year. Hospital costs have also been shown to decrease with intensivist staffing. In addition to intensivists, the presence of emergency response and code teams has been shown to decrease in-hospital mortality. Higher nurse education and oncology training and improved nurse/patient ratios have also been associated with decreased mortality. Hospitals that provide 24-hour in-house staffing of specialists such as trauma surgeons also show reduced costs, more prompt treatment, and reduced mortality. Centers that have adopted clinical management pathways specific to pancreatic surgery have been able to shorten length of stay despite operating on older patients and expanding indications for pancreatic surgery.

Second, high-volume centers may have specific resources readily available to be used in the diagnosis or detection and management of complications. A specific example is the increasing use of interventional radiology techniques. An evaluation of 1061 patients who underwent pancreaticoduodenectomy revealed that 44% had interventional radiologic procedures including pre- or postoperative biliary drainage, angiography and embolization of postoperative bleeding, or postoperative drainage of abscess, bilioma, or lymphocele. In addition to interventional radiology, many high-volume centers have access to interventional gastroenterology staff and equipment. Interventional gastroenterologists can play a role in diagnosis and staging of pancreatic cancer through various techniques including targeted lymph node sampling using endoscopic ultrasound or endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP). Furthermore, interventional gastroenterologists can assist in managing postoperative complications through techniques such as stenting pancreatic ducts to relieve pancreatic fistula output after distal pancreatectomy. Another set of resources that may be more readily available at high-volume centers are cutting-edge radiologic imaging techniques and equipment. In addition to high-quality, thin-slice computed tomography scanners with digital reconstruction along with Web-based image archiving; many high-volume centers also have secretin-enhanced magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (s-MRCP) available. The advent of s-MRCP allows for the diagnosis of pancreatic complications such as fistulas without the high risk of bacterial contamination associated with ERCP.

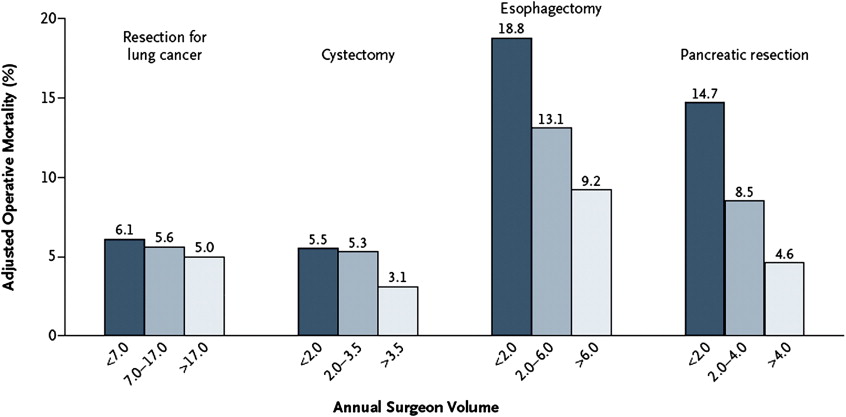

A third explanation for the lower mortality and improved outcomes noted at high-volume centers is that the surgeons at high-volume centers may be more highly trained and experienced. Advanced surgical training, regardless of the specific field of specialty, is associated with improved outcomes in hepatopancreatobiliary surgery. Surgeon experience has been shown to be associated with lower mortality in pancreatic cancer resection since the 1980s. Birkmeyer and colleagues showed that surgeon volume was inversely related to operative mortality across 4 cancer procedures. Among the cancer procedures studied, surgeon-specific volume had the greatest impact in lower mortality for esophagectomy and pancreatic resection ( Fig. 3 ). A meta-analysis of more than 54,000 articles found that high surgeon volume and specialization are associated with improved patient outcome across various procedures. An evaluation of pancreatic resections across 26 university hospitals showed that surgeons who performed 1 to 3 pancreatic resections had more complications than those who performed 4 or more resections ( P = .011). Although older surgeon age has been shown to be associated with higher mortality in pancreatectomy (OR 1.67; 95% CI 1.12–2.49), this difference dissipates with increasing surgeon volume. Regardless, the average age of surgeons in the United States is rising, and current surgical residents are exposed to few pancreatic resections in training. Surgical residents typically graduate from training programs with fewer than 5 hepatopancreatobiliary surgeries requiring additional fellowship training. The availability of surgeons with advanced training, including fellowship experience, may not yet be sufficient in numbers or adequately distributed geographically, and this may lend credence to regionalization to centers of high volume and specialty-trained surgeons.

With increasing evidence that higher-volume centers have improved outcomes, there has already been a trend toward regionalization. McPhee and colleagues showed the proportion of procedures performed at high-volume centers in the United States has increased from 30% to 39% from 1998 to 2003 ( P <.0001). Regionalization has been observed in individual states such as Texas, where high-volume centers performed 54.5% of pancreatic resections in 1999 and 63.3% in 2004 ( P = .0004). A classic example of regionalization in Maryland shows an increase in pancreatic resection volume at a single high-volume center. From 1984 to 1995, volume of patients managed at the single center increased from 20.7% to 58.5% of all pancreatic resections in the state, with a concurrent drop in mortality from 17.2% to 4.2%.

In Europe geographic proximity and nationalized health care systems have facilitated regionalization. Regionalization of pancreatic surgery in Finland has been endorsed to decrease postoperative morbidity and mortality. A review from the Netherlands shows that pancreatic resections are slowly being regionalized to high-volume centers. From 1994 to 1996 65.4% of resections were performed at low-volume centers and decreased to 57.3% from 2001 to 2003. Specialized care units have been created in the United Kingdom and have been shown to have mortality on a par with specialized care units outside the United Kingdom and superior outcomes compared with nonspecialized units. Beyond pancreatic cancer surgery, regionalization of health care in Europe has been successful. Regionalization of patients with ovarian cancer to specialized centers in the Netherlands has been associated with improved outcomes. Regionalized care of preterm babies in Europe has been studied and proposed as a model for improving outcomes and resource use.

The argument in favor of regionalizing pancreatic cancer care is an attempt to save lives. An analysis of patients undergoing various procedures in California found that for patients undergoing pancreatic cancer surgery, 74% of in-house mortality observed in low-volume hospitals could have been avoided if patients were treated in high-volume hospitals. The same study found that across all conditions studied, more than 600 deaths could have been avoided with regionalization of care. Adherence to the Leapfrog Group standards for minimal surgical volumes can potentially save an estimated 8000 lives annually, including 177 potential deaths after pancreatectomy. An analysis of the NCDB studied 60-day mortality and 5-year survival at low- and high-volume centers for 7 cancers including pancreatic cancer. Across the 7 cancers studied, it was estimated that 2207 perioperative deaths and 7245 long-term deaths could have been potentially avoided if outcomes at lower-volume hospitals were improved to the level of those with the highest volumes ( Table 1 ). Specifically for pancreatic cancer, there were 225 potentially avoidable perioperative deaths and 491 potentially avoidable long-term deaths each year if cases at lower-volume centers were shifted to high-volume centers. Despite this evidence in favor of regionalization, pancreatic resections are still performed at hospitals considered low-volume.

| Cancer Type | Cases/Year | Resection Rate (%) | Potentially Avoidable Perioperative Deaths | Potentially Avoidable Long-term Deaths |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Colon | 112340 | 88.9 | 701 | 2700 |

| Esophagus | 15560 | 29.0 | 127 | 522 |

| Liver | 19960 | 35.4 | 245 | NS |

| Lung | 213380 | 28.6 | 596 | 1444 |

| Pancreas | 37170 | 19.0 | 225 | 491 |

| Rectal | 41420 | 80.3 | 134 | 1595 |

| Stomach | 21260 | 51.0 | 179 | 493 |

| Total | 461090 | 2207 | 7245 |

Problems with regionalization

Several major limitations exist to regionalizing pancreatic cancer care resection in the United States. First, there may be a lack of enough high-volume centers to handle the national volume. The Leapfrog Group considers 11 annual pancreatic resections the minimum in designating a hospital as high-volume. Of patients undergoing pancreatic resections in the United States, 60% are treated at hospitals with fewer than 11 cases per year. In dissecting hospital service areas and referral patterns, only a small percentage of regions in the United States have a high-volume hospital to which to send pancreatic resection candidates. Considering 80% of cancer care in the United States is provided at small hospitals, purely volume-based referral would inundate the high-volume providers. If all cases performed at low-volume hospitals were to be referred only to the highest-volume hospitals, many patients could expect increased times from diagnosis to surgery. Wait times for cancer surgery have increased more than 20% in the last decade and regionalization to fewer centers may fuel this trend. Considering that with pancreatic cancer eventual development of advanced disease including nodal and liver metastases is common, delay in treatment would not be considered acceptable. Furthermore, patient factors after a cancer diagnosis such as anxiety and decreased productivity could lead to a loss to follow-up and affect cancer progression.

Central to the discussion of high- versus low-volume hospitals is defining the exact number of cases that designate the volume cut-offs. The studies on pancreatic resection have varied from designating low volume from 2 to 200 resections per year. Those hospitals at the ends of the spectrum, high-volume and low-volume, are easier to identify and categorize. The more difficult topic to address is defining a moderate-volume hospital. The potential benefits of being designated a high-volume hospital may motivate individual surgeons or centers to perform more cases, possibly leading to unnecessary surgeries simply to gain a high-volume designation status. The ramifications of low-volume hospitals referring all cancer-related pancreatic surgery to high-volume hospitals leads to a slippery slope of referral. If a hospital has less experience with pancreatic resection cases, a surgeon and medical staff may become less equipped to handle other similar cases. Lower-volume hospitals, as employers, may not be able to attract or retain surgeons interested in performing these procedures.

An argument against regionalization is that referral of pancreatic cancer operations away from low-volume centers may have financial ramifications at the hospital and provider level. Considering many studies designate that low- and lowest-volume hospitals perform 2 or fewer pancreatectomies annually, the loss in experience incurred with regionalization of cases away from these institutions would be minimal. Although some elective cases may be referred away from low-volume hospitals with regionalization, it is unlikely that surgeons rely on these procedures to maintain their practices. In the United States regionalization trends for pancreatic resection have been noted without a significant effect on the case volume or revenue for low-volume hospitals.

Another potential limitation to regionalization of patients to a specialized, high-volume center is that patients have to travel farther away from home. The potential travel burden not only affects the patient but also may limit access to the patient’s family and sources of social and emotional support. Overall, there is an inverse relationship between distance to health care services and use. In addition to the travel required for an initial cancer resection, travel would be required for follow-up visits. Many patients prefer to have surgery at local hospitals even with the knowledge that mortality risk would be decreased with travel to regional centers. Specific patient populations such as elderly people may have added resistance to traveling for care. Travel distance could delay initial pancreatic resection or evaluation of postoperative complications.

In response to the travel distance and travel time limitations, an assessment of patients undergoing pancreatectomy found that many patients traveled past higher-volume hospitals to undergo surgery at a low-volume hospital. In comparing potential travel times for patients, the travel times would increase according to the volume cut point set for the regional referral centers. With a modest-volume requirement, travel times would increase by approximately 30 minutes, whereas with high-volume standards travel times would increase by 1 to 2 hours. These findings were most dramatic for patients who live in rural areas, who would typically have to travel farther to reach high-volume centers. Another study examining travel times to high-volume hospitals echoed these results and found that 20.6% of patients traveled farther to low-volume hospitals than they would have traveled to reach the nearest high-volume center. Although outcomes and mortality may be most improved with referral to only the high-volume centers, patient travel time and distance limitations could be temporized by referral to moderate-volume hospitals.

Some argue a potential clinical limitation to regionalization to high-volume centers involves patients who are in need of immediate treatment or are too ill to be referred away from a low-volume hospital. Although this is a valid point in disease processes that require a trip to the operating room within a short period of time from admission, some patients with pancreatic cancer are admitted emergently for their initial cancer resection. In fact, 1 study examining selective referral to high-volume centers showed that 29% of the patients admitted emergently to low-volume centers for procedures had their operations more than 3 days after admission. Many of these patients may have been stable enough for transfer after admission, allowing for surgical intervention to be delayed and conducted at a high-volume center.

Another drawback to the volume-based referral system includes polarizing hospitals and providers to extremes of the spectrum of health care: either capable or not. There are many high-volume centers that have poor outcomes and opposing low-volume centers with excellent outcomes. An evaluation of high-volume centers in Texas found that there is considerable variation in outcomes among the centers after adjusting for differences in demographics, risks of mortality, and disease severity. The availability of specific clinical resources may explain some of the association between high-volume hospitals and improved outcomes. Low-volume centers with excellent clinical resources have been shown to have low perioperative mortality. The underpinning question of why high-volume centers have better outcomes has not been well studied, and until more suitable measures of quality are determined, volume remains the best approximation of quality in pancreatic cancer resection despite documented exceptions.

With a lack of enough high-volume centers in all geographic regions, referral across state borders and health care system boundaries may be required. The current multipayer system that exists in the United States may prove to be prohibitive to referral across these borders and boundaries. For many older patients who qualify for nationally subsidized Medicare plans, these limitations are less restrictive. The Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services has endorsed minimum-volume requirements in Medicare patients undergoing organ transplantation. Current estimates place approximately half of patients undergoing pancreatectomy qualifying for Medicare, leaving many patients at the financial mercy of their insurance providers for referral to high-volume centers.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree