Rationale

Each person with diabetes is unique. People with diabetes focus on being well and living a normal life, thus, they strife for life balance. Achieving a balanced lifestyle and good quality of life is essential to the physical and psychological well being of people with diabetes. Depression is more common in people with diabetes and can impact on their self-care and long-term health outcomes. Health professionals are often preoccupied with metabolic control. Changing the focus to achieving balance is more likely to assist the person to achieve metabolic control. Health professionals’ goal is to achieve optimal metabolic outcomes: a common goal of people with diabetes is to achieve a healthy life balance. Achieving such balance is a complex and changing process.

Introduction

People with diabetes are at increased risk of developing various degrees of psychological distress and psychological disorders including depression and eating disorders (Rubin & Peyrot 2001). Symptoms associated with hyperglycaemia, hypoglycaemia and the focus on diet can mask signs of psychological distress and disorders. If present, psychological disorders can interfere with self-care, medicine adherence and exacerbate hyperglycaemia, thus setting up a vicious cycle. Depression is often undetected in older people and is often considered to be part of normal ageing. Approximately 15% of older community dwelling older people experience depressive symptoms and at least 24% of people with diabetes of all ages are depressed (Goldney et al. 2004) the incidence rises sharply in older people living in residential facilities. In Australia, the second highest suicide rate occurs in men >85.

The decision to take control of diabetes and undertake self-care is vital Hernandez (1995). Hernandez found people with Type 1 diabetes were initially concerned with being normal and adopted a passive role in their care. The decision to assume control often occurred at a turning point in their lives. The impetus for assuming control include feeling betrayed by or not listened to by health professionals, realising that adhering to management regimens would not automatically prevent complications, and health professionals accusing them of ‘cheating’ when their blood glucose levels were unstable (Patterson & Sloan 1994). Life and other events may impact on an individual’s willingness and ability to assume control because of work, religious, cultural, social, and health-related issues. These include:

- Knowing their body and being able to differentiate normal from abnormal. Currently, most diabetes education and management programmes focus on the abnormal or assume all people respond the same way, the way the ‘average person’ responds.

- Knowing how to manage diabetes and having the physical and mental capability to manage the self-care tasks and problem-solve in a range of situations.

- Having supportive, constructive relationships in place with family/carers/friends and health professionals.

- Positive attitudes, resilience and adaptive coping mechanisms.

- Health professionals knowing the person with diabetes in order to understand their feelings about diabetes, the lessons they learned for living with diabetes and the way they manage self-care.

Psychological adaptation and maintaining a good quality of life is dependent on the individual’s degree of resilience. Resilience refers to the ability to overcome adversity and not only to rise above it, but also to thrive. It has its foundation in belonging, life meaning and expectations and happiness. Resilience is at the heart of spirituality, social cohesion, and empowerment.

Chronic conditions such as diabetes have a major impact on an individual’s life plan, their partner, families, and other relationships. Acquiring coping skills and being resilient have positive effects on emotional well being and therefore on physical outcomes. Coping with diabetes is an issue for some people. Coping issues for young people with Type 1 diabetes centres around:

- being expected to cope

- being expected to cope all the time

- being seen to cope by others

- having to cope for the rest of their lives

- no respite from coping with diabetes (Dunning 1994).

These issues are important across the lifespan as people with diabetes face life’s challenges.

This chapter presents a brief outline of the complex psychological and quality of life aspects of having diabetes. Reactions to the diagnosis of diabetes are unique to the individual concerned; however, several common reactions have been documented. They include: anger, guilt, fear, helplessness, confusion, relief and denial. Appreciating some of the issues involved will enable nursing staff to better understand the complexity of living with diabetes and help the individual plan appropriate care.

Many factors influence how a person reacts to and accepts the diagnosis of diabetes and assumes responsibility for self-care. These factors include:

- age

- gender

- existing knowledge about diabetes

- general and health beliefs

- locus of control

- spirituality

- family support

- social, cultural and religious attitudes.

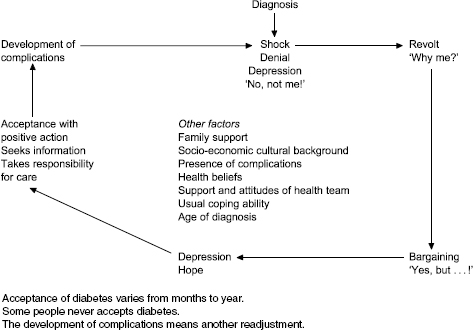

A period of grief and denial is normal. Figure 15.1 is one model of the ‘diabetic grief cycle’ loosely based on Helen Kubler Ross’ work, associated with death and dying. Lack of knowledge, or inaccurate knowledge about diabetes, produces stress and anxiety. The invisible nature of the condition – in Type 2 diabetes and most diabetic complications there are often no presenting symptoms e.g. MI, UTI and retinopathy are silent – can lead to disbelief and denial of the diagnosis. Denial is appropriate early in the course of the disease and enables people to maintain a positive attitude and cope with the altered health status.

Adequate time must be allowed for the person to grieve for their perceived losses, for example, loss of spontaneity, lifestyle, having to plan ahead, loss of the respect and love of the people they value (DAWN 2004) and a changed body image. However, prolonged denial can inhibit appropriate self-care, cause people to ignore warning signs of other problems and can lead to failure to attend medical appointments increasing the risk of diabetes complications. Denial can continue for longer than 5 years after the initial diagnosis in people with Type 1 diabetes (Gardiner 1997). Inadequate self-care could also indicate burnout from the unremitting demands of living with diabetes and lead to frequent use of health services by some people with diabetes.

Figure 15.1 Model of the diabetic grief cycle.

Accepting diabetes involves dealing with some or all of the following:

- mental and physical pain

- hospitalisation or frequent outpatient or doctor visits

- the health system, including health professional’s beliefs and attitudes, and often hospitals and emergency services

- lifelong treatment

- body image changes

- friends/family relationships

- fluctuating blood glucose levels

- emotional lability

- loss of independence

- societal attitudes and expectiations.

The tasks required to maintain acceptable blood glucose control are tedious and sometimes painful. There are financial costs involved, which can be a burden for some people (insulin, testing equipment, doctors’ visits, increased insurance premiums). They add to the stress associated with having a disease they did not want in the first place.

Clinical observation

There is no holiday from diabetes for the patient. The individual has to live with diabetes 365 days a year 24-hours a day for the rest of their life.

Managing a chronic illness means straddling two paradigms – the biomedical and the psychosocial, neither adequately address spirituality, they all need to be integrated in order to achieve optimal health outcomes. An individual’s path through life is influenced by life trajectories and turning points and these include the diagnosis of diabetes, expectations of treatment, and social support. Helping an individual define their life trajectory and identify turning points is part of holistic care.

In the context of this book, spirituality refers to the dimension of self that provides a framework for finding meaning and purpose in life and can be a motivating force that enables the individual to transcend life’s trials such as the diagnosis of diabetes (Parsian & Dunning 2008). Hodges (2002) described four dimensions of spirituality, which each play a role in the incidence and degree of happiness or depression an individual experiences:

Interestingly, Wolpert (2006) described depression as ‘soul loss.’ Parsian and Dunning (2008) found a significant association among spirituality, being female, higher education, duration of diabetes <10 years, lower HbAlc and higher self-concept in young adults with diabetes. There was no significant association with religion. Spirituality may or may not encompass religion. Over the past 10 years research has demonstrated a link between being affiliated with a religious group and better physical and mental health outcomes although the association is not clear and may have a cultural element (UK Mental Health Foundation 2006; Gilbert 2007).

Diabetes has a ‘bad reputation’ in the community, with many associated myths, for example, ‘eating sugar causes diabetes’, and Type 2 diabetes is a mild form of the disease, which must be discussed and dispelled. Such myths can be associated with self-blame and guilt feelings. In addition, social pressures and ignorance often cause frustration and contribute to denial of the diabetes and failure to follow medical advice. For example, ‘A little piece of cake won’t hurt you’ and is confusing for people with Type 1 and Type 2 diabetes.

Depression

The World Health Organisation predicts that depression will be the second major health issue by 2020. In Australia 5.8% of adults experience a depressive disorder (Andrews et al. 1999) and account for 8% of non-fatal disease burden. People with diabetes have a higher incidence of depression than the general public and the depression often precedes the diagnosis of diabetes. Depression may be an independent risk factor for diabetes (Rubin & Peyrot 2002). However, the mechanism linking diabetes and depression and whether depression precedes diabetes or diabetes leads to depression is unclear (Eaton et al. 1996; Peyrot 1997; Carnethon et al. 2003). Lustman (1997) suggested depression and hopelessness arise from having a chronic disease. Likewise, it is not clear whether depression increases the risk of diabetes per se or through the associated lifestyle risk factors such as poor diet, smoking and inactivity. Carnethon et al. (2003) found depression was associated with lower than high school education in a cohort from the NHANES 1 study (n = 6910): low education was independent of risk factors for developing diabetes. They proposed causal mechanisms could include genetic predisposition, inflammation and activation of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis, similar to those proposed for the association among diabetes, cardiovascular diseases and depression, see Chapter 8.

Depression could be a component of the insulin resistance syndrome (see Chapter 1). People who are depressed are more likely to have inadequate self-care, present to the emergency department, require specialist intervention and exhibit lowered self-worth and physical functioning (Ciechanowski et al. 2000). The course of depression in people with diabetes is chronic and severe and depressive episodes may be particularly severe because of the metabolic effects (uncontrolled diabetes) and the neuroendocrine response (Rubin & Peyrot 2001). Thus, depression is associated with increased health care costs (Egede et al. 2002).

Cavan et al. (2001) suggested the reasons for depression in people with diabetes might be:

- The heavy disease burden.

- The strain diabetes places on relationships, especially family relationships.

- The stigma of diabetes in the family and the community.

- Shock and guilt at the diagnosis that are not adequately addressed and resolved.

- The uncertainty of the future.

- Loss of control.

- Past negative experiences with health professionals.

The perceived severity of diabetes affects the person’s mental status. Type 2 diabetes has traditionally been considered to be less serious than Type 1 diabetes especially where it is treated without medications, even though Type 2 diabetes is a progressive disease of beta cell failure and complications are frequently present at diagnosis. Health professionals often convey these beliefs (Dunning & Martin 1997, 1999). Such messages convey false hope, and depression and stress occur when insulin is required. Considering the silent, insidious nature of Type 2 diabetes and the frequency with which complications are present at diagnosis, it is hardly a mild disease.

Symptoms of depression

The presence of five or more of the following signs every day for >2 weeks are suggestive of depression and should be formally assessed (US National Institute of Mental Health 2002):

- Persistent low mood, feeling sad, hopeless, anxious or empty

- Pessimism

- Feeling guilty, worthless or helpless, loss of interest in usual activities such as work, hobbies, and sexual relationships

- Low energy, fatigue

- Difficulty concentrating, remembering, making decisions

- Insomnia, waking early, oversleeping

- Appetite and/or weight changes

- Suicidal thoughts or attempts or dwelling on death

- Irritability.

In addition, depression is characterised by reduced confidence and neglect of self-care in people with diabetes. However, not all people who neglect their self-care are depressed and assumptions must always be checked (Lustman et al. 1996).

Maintaining mental health and managing depression

‘The effectiveness of interventions depends on the context in which it is delivered’ (Wilson 2001). The way the health professional interacts and delivers care may be more important than the care itself (Balint 1955). While this is an old study its message is still relevant today and many Balint Groups have been established especially in the US to help health professionals become more effective carers. Managing depression and diabetes is complex. Complexity theories suggest all the circumstances that influence behaviour must be considered (Lancaster 2000). This is certainly true of diabetes and depression where individuals:

- Operate within self-adjusting biochemical, cellular, physiological, social, cultural and religious systems. A change in one will result in a change in the others.

- Illness and wellness are part of a continuum, are dynamic and arise from an interaction among these factors.

- Physical and psychological health can only be maintained using an holistic model of care that incorporates all of these aspects.

- Counselling strategies such as cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) (Lustman et al.1998) and interpersonal therapy (Frank et al. 1991) have been shown to reduce self-defeating thought patterns and negative behaviours and improve adherence with management regimens. Clinicians can use counselling strategies in routine care. For example, Elley et al. (2003) showed counselling in general practice effectively increased physical activity and improved quality of life over 12 months. In a second study (Elley et al. 2007) found a personalised approach focusing on barriers and facilitators to physical activity, internal motivators, recognising time, physical and psychological limitations and spiritual benefits as well as the role of significant others, was important. CBT requires the individual to be able to think rationally and actively participate in their management. Usually, a close working relationship with the therapist is needed and it may take months for the individual to change unhealthy thought/behaviour patterns (Better Health Channel 2007).

- Coping strategies including problem-focused coping to deal with or prevent problems and emotion-focused coping to deal with negative emotions (Peyrot & Rubin 2007).

- Enhancing diabetes-specific self-efficacy, which involves encouraging realistic expectations and enhancing motivation by helping people identify their successes and encouraging optimism and realistic expectations. For example, motivational interviewing (Rollnick et al. 1999). High self-efficacy is associated with lower rates of depression (Steunenberg et al. 2007) and spirituality (Parsian & Dunning 2008).

- Improving metabolic control to relieve the effects of hyperglycaemia and fear of hypoglycaemia on mood and quality of life.

- Interactive behaviour change technology (IBCT), which includes PDAs, patientcentred Internet websites, coaching telephone calls, DVDs, audiotapes, touch screen kiosks designed to help maintain patient independence, can help people improve their diabetes self-care and monitor change (Piette 2007). They can also be useful in supporting informal caregivers and promoting activity, for example, pedometers. People search the Internet for information about depression more than any other condition (Taylor 1999). The Internet enables people to remain anonymous, which is important to some people (Rasmussen et al. 2007). People need advice about how to assess the veracity of websites because the information is often of low quality and may be misleading. Griffiths & Christensen (2002) undertook a cross-sectional study of 15 Australian depression Internet sites in November and December 2001 and found the quality of the content of many sites was poor. Sites receiving the highest rating were beyond Blue, BluePages, CRUIAD and InfraPsych. However, information technologies do not take the place of human contact and are more effective when combined with human contact (Piette 2007).

- Complementary therapies (CAM) and self-help programmes. CAM with the best evidence for effectiveness are Hypericum perforatum for mild–to-moderate depression, exercise, bibliotherapy involving CBT and light therapy for winter depression. There is limited evidence to support acupuncture, light therapy for SAD syndrome, massage therapy, relaxation therapies, SAM-e, folate and yoga breathing exercises (Jorm et al. 2002). CAM medicines should be used under the supervision of a qualified practitioner.

- Identifying and treating underlying psychological/psychiatric disorders such as depression, and eating disorders and referring the individual to appropriate mental health services early. Counselling and/or antidepressant medicines may be needed. Antidepressant medicines such as serotonin reuptake inhibitors are commonly used and are effective in people with diabetes (Rubin & Peyrot 1994). The individual’s previous experience with antidepressant medicines and the likely side effects need to be considered. As indicated, depression is a chronic condition and regular monitoring is essential and needs to be incorporated into routine care including in the acute care setting using screening tools such as:

- Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS).

- Depression Anxiety Stress Scale (DASS).

- Beck Depression Inventory (BDI (Beck 1974)).

- Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) (Radloff 1977).

- Geriatric Depression Score.

- K-10 Profile.

- Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ–9) (Spitzer et al. 1999).

- Brief Case Finding for Depression (BCD) (Clarke).

- Diabetes-Specific Quality of Life ° Diabetes Health Profile ° AddQoL

- Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-1V 1994).

- Wellbeing Enquirey for Diabetes.

- World Health Organization Well Being Index (WHO-5) especially in older people (Bonsignore et al. 2001).

- Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS).

In order to achieve these goals health professionals need to ask good questions that aim to elicit a specific response, for example, ‘ what is the hardest thing about living with diabetes for you at the moment?’ to identify the key issue to be addressed. Focus on successes and support the individual’s problem-solving skills, for example, ‘How do you think you can manage that?’ Involve the family and significant others if relevant and with the individual’s permission. Develop emotional resilience and optimism.

Antipsychotic medications and diabetes

Second generation antipsychotic medications effectively treat a range of psychiatric disorders and offer many benefits over older medications such as chlorpromazine and haloperidol (Wirshing et al. 2002; DeVane 2007). However, they do have significant side effects, namely rapid weight gain, hyperlipidaemia and insulin resistance, that can affect metabolic control and increase the cardiovascular risk in people with established diabetes and cause hyperglycaemia in non-diabetics, however, there is considerable variability in responses among individuals receiving the same medication.

A consensus panel of experts from the American Diabetes Association, American Psychiatric Association, the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and the North American Association for the study of Obesity (2004) recommended:

- Assessing weight, blood glucose, lipids and blood pressure before starting antipsychotic medicines or as soon as possible after.

- Actively managing these conditions, if present.

- If weight increases by >5%, consider changing to another antipsychotic less likely to cause metabolic effects.

- Antipsychotics listed in order of those with the most to the least metabolic effects are: olanzapine, quetiapine, risperidone, ziprasidone, aripiprazole. These medicines still cause weight gain.

- Institute lifestyle modification to mange weight if possible, which will involve helping the person adhere to advice.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree