Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) is the most common type of lymphoma in the western world. Current treatment regimens result in curing approximately 50% to 60% of patients with DLBCL. In 2006, the Food and Drug Administration approved rituximab for use in the first-line treatment of patients with DLBCL in combination with anthracycline-based chemotherapy regimens. Since then, no other agents have been approved for the treatment of DLBCL. This article reviews recent data on the most promising agents in development for the treatment of DLBCL.

Key points

- •

DLBCL is the most common type of lymphoma in the western world.

- •

No single agent has been approved for the treatment of DLBCL in more than a decade.

- •

Agents targeting B-cell receptor signaling, Bcl2 protein, and PD1 immune checkpoint, have modest single-agent activity in relapsed DLBCL.

Introduction

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) is the most common subtype of adult lymphomas, accounting for approximately 25,000 new cases per year in the United States. Today, the most widely used regimen for the treatment of DLBCL is RCHOP (rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone). Historically, the CHOP regimen was introduced in the early 1970s. More than 40 years later, the only major therapeutic advancement has been incorporation of the monoclonal antibody rituximab with CHOP, creating the RCHOP regimen. Despite this progress, approximately 50% of patients have disease progression or relapse after RCHOP, and most die of their disease. Accordingly, new treatment modalities are necessary to improve the cure rate of patients with DLBCL.

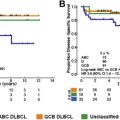

At the molecular level, DLBCL is a heterogeneous disease. Hence, it is not surprising that many patients do not respond to standard RCHOP therapy. Gene expression profiling studies demonstrated that DLBCL is broadly classified into germinal center B-cell (GCB)-like and activated B-cell (ABC)-like subtypes. Using this “cell of origin” classification, it has been shown that treatment with standard RCHOP regime results in a better cure and overall survival in patients with the GCB subtype when compared with those with the ABC subtype. However, relapses are observed in both subsets after RCHOP therapy, suggesting the existence of additional oncogenic events that mediate resistance to RCHOP, irrespective of the cell of origin. More recent genome sequencing studies revealed a more complex molecular heterogeneity of DLBCL, with genetic alterations frequently observed in GCB and ABC subtypes. Other, less common genetic alterations can preferentially be detected in either GCB or ABC subsets. Novel treatment strategies that are based on lymphoma-associated oncogenic alterations are needed to improve the cure rate of patients with DLBCL.

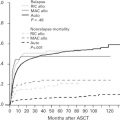

One of the biggest challenges in drug development for patients with cancer, including DLBCL, is the high failure rate caused by excessive toxicity, low response rates, or both ( Fig. 1 ). The success of future drug development in DLBCL depends on using biomarkers to identify patients who are likely to benefit from a specific therapy. The following is a focused review on the most promising agents for the treatment of DLBCL, with a discussion on how to select patients for these novel drugs based on genetic and molecular biomarkers. This article also provides a brief update on recent advances in immune therapy of DLBCL.

Introduction

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) is the most common subtype of adult lymphomas, accounting for approximately 25,000 new cases per year in the United States. Today, the most widely used regimen for the treatment of DLBCL is RCHOP (rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone). Historically, the CHOP regimen was introduced in the early 1970s. More than 40 years later, the only major therapeutic advancement has been incorporation of the monoclonal antibody rituximab with CHOP, creating the RCHOP regimen. Despite this progress, approximately 50% of patients have disease progression or relapse after RCHOP, and most die of their disease. Accordingly, new treatment modalities are necessary to improve the cure rate of patients with DLBCL.

At the molecular level, DLBCL is a heterogeneous disease. Hence, it is not surprising that many patients do not respond to standard RCHOP therapy. Gene expression profiling studies demonstrated that DLBCL is broadly classified into germinal center B-cell (GCB)-like and activated B-cell (ABC)-like subtypes. Using this “cell of origin” classification, it has been shown that treatment with standard RCHOP regime results in a better cure and overall survival in patients with the GCB subtype when compared with those with the ABC subtype. However, relapses are observed in both subsets after RCHOP therapy, suggesting the existence of additional oncogenic events that mediate resistance to RCHOP, irrespective of the cell of origin. More recent genome sequencing studies revealed a more complex molecular heterogeneity of DLBCL, with genetic alterations frequently observed in GCB and ABC subtypes. Other, less common genetic alterations can preferentially be detected in either GCB or ABC subsets. Novel treatment strategies that are based on lymphoma-associated oncogenic alterations are needed to improve the cure rate of patients with DLBCL.

One of the biggest challenges in drug development for patients with cancer, including DLBCL, is the high failure rate caused by excessive toxicity, low response rates, or both ( Fig. 1 ). The success of future drug development in DLBCL depends on using biomarkers to identify patients who are likely to benefit from a specific therapy. The following is a focused review on the most promising agents for the treatment of DLBCL, with a discussion on how to select patients for these novel drugs based on genetic and molecular biomarkers. This article also provides a brief update on recent advances in immune therapy of DLBCL.

B-cell receptor signaling inhibitors

The B-cell receptor (BCR) complex is composed of membrane IgM that is linked with transmembrane heterodimer protein (CD79a/CD79b). Both CD79 proteins contain an immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motif in their intracellular tails. On BCR crosslinking by an antigen, the CD79a immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motif tyrosines (Tyr188 and Tyr199) are phosphorylated, creating a docking site for Src-homology 2 domain-containing kinases, such Lyn, Blk, and Fyn, with subsequent activation of downstream kinases, such as spleen tyrosine kinase (Syk) and bruton tyrosine kinase (Btk). Aberrant and sustained activation of BCR signaling pathway is implicated in the pathogenesis of a variety of B-cell malignancies, including DLBCL. Novel drugs targeting various components of BCR signaling pathway have been developed, initially targeting SYK, and subsequently targeting BTK.

Spleen Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors

SYK is a nonreceptor tyrosine kinase important for the development of the lymphatic system. SYK is expressed in cells of the hematopoietic lineage, such as B cells, mast cells, basophils, neutrophils, macrophages, and osteoclasts, but is also present in cells of nonhematopoietic origin, such as epithelial cells, hepatocytes, fibroblasts, neuronal cells, and vascular endothelial cells. Thus, SYK seems to play a general physiologic function in a wide variety of cells. Syk −/− knockout mice die during embryonic development of hemorrhage and show severe defects in the development of the lymphatic system. Fostamatinib disodium (R788), a competitive inhibitor for ATP binding to the Syk catalytic domain, demonstrated a 55% response rate in patients with relapsed chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL). Patients with other B-cell malignancies had a lower response rate to fostamatinib. In a recent study, 68 patients with relapsed or refractory DLBCL, fostamatinib treatment resulted in a 3% response rate. None of the patients with clinical benefit had ABC genotype.

Bruton Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors

BTK inactivating mutations impair B-cell development and are associated with the absence of mature B cells and agammaglobulinemia. Ibrutinib is a selective and irreversible inhibitor of BTK. Although ibrutinib demonstrated a significant clinical activity in patients with CLL, mantle cell lymphoma, and Waldenström macroglobulinemia, it has a modest clinical activity in DLBCL and follicular lymphoma. In relapsed DLBCL, ibrutinib treatment resulted in an overall response rate of 23%. In contrast to the results that were observed with the SYK inhibitor fostamatinib, most responses to ibrutinib were observed in patients with the ABC DLBCL subtype. This observation generated interest in further investigating ibrutinib in combination with standard chemotherapy regimens for the treatment of patients with newly diagnosed ABC DLBCL. A phase 3 randomized trial comparing RCHOP with RCHOP with ibrutinib combination (the Phoenix study) has already completed enrollment of patients with newly diagnosed non-GCB DLBCL, and the results should become available in the near future.

Ibrutinib is generally more tolerated than SYK inhibitors. The most common toxicities are diarrhea and skin rash. Grade 3 to 4 neutropenia and thrombocytopenia are seen in less than 10% of patients. Other toxicities include atrial fibrillation and bleeding. Ibrutinib covalently binds to a cysteine 481 (C-481) residue in the BTK kinase domain ( Fig. 2 ). Several other kinases that contain C-481, including members of the TEC family, EGFR, and JAK3, are also inhibited by ibrutinib, which may contribute to its toxicity. To reduce toxicity, several pharmaceutical companies are developing more selective BTK inhibitors. These second-generation, selective, BTK inhibitors, including acalabrutinib and BGB-3111, also bind to C481. Accordingly, these newer inhibitors are not expected to be more effective than ibrutinib, nor they are expected to work in ibrutinib failures. However, because these selective inhibitors may be more tolerable than ibrutinib, they may be administered without dose interruption or reduction. Whether an uninterrupted treatment schedule will be associated with a more favorable treatment outcome is currently unknown.