Prominent Ductal Patterns

Linear densities on the mammogram may represent arteries, veins, and lactiferous ducts. There should be no confusion between vascular shadows and ducts.

Lactiferous ducts are linear, slightly nodular densities that radiate back from the nipple into the breast. The normal lactiferous ducts are thin, measuring 1 to 2 mm in diameter, and often are not evident as separate structures on mammography. Enlarged ducts may occur in benign and malignant conditions. When ducts are enlarged, correlation with clinical examination as to the presence of discharge is important. Galactography is of help in providing further information in the evaluation of a nipple discharge, with or without dilated ducts being seen on mammography.

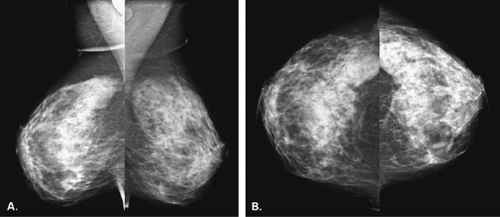

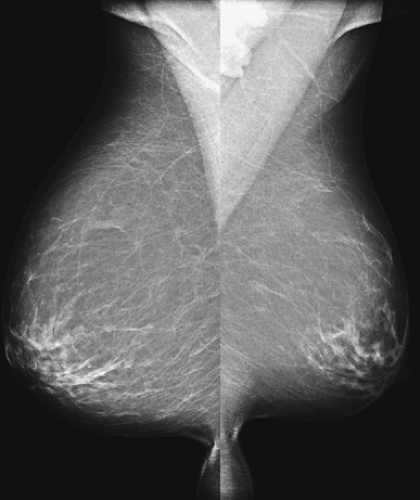

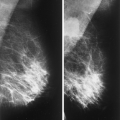

A diffusely prominent ductal pattern bilaterally (Fig. 7.1), associated with small nodular densities, has been described by Wolfe et al (1,2) as placing the patient at higher-than-average risk for developing breast cancer. According to Wolfe, the breast parenchyma was classified into four patterns: N1 or fatty replaced, and P1, P2, or DY with increasing amounts of ductal or glandular tissue. Because of surrounding collagen, individual ducts may not be identified; instead, a dense, triangular fan-shaped density is present beneath the areola (3). The association between a prominent ductal pattern and breast cancer incidence has been debated, with some authors (4,5) agreeing with the association and others (67) finding no reliable indicator of risk by mammographic pattern. Ernster et al. (9) suggested that nulliparous women and women with a family history of breast cancer are more likely to have dense breasts and a prominent ductal pattern and that breast parenchymal pattern may be related to other risk factors. Funkhouser et al. (10) found a twofold increase in breast cancer risk in women with a P2 or DY Wolfe pattern in comparison with an N1 pattern (fatty breasts). Andersson et al. (11) also found an increased frequency of the dense ductal patterns with advancing age at first pregnancy and with nulliparity. Brisson et al. (12) assessed breast cancer risk as related to parenchymal pattern in a study of 3,412 women and found that parenchymal pattern was strongly correlated with risk. The authors found that the risk of breast cancer was five- to sixfold greater in women who had breasts that were composed of 85% or more dense tissue than in women who had no density on mammography.

Duct Ectasia

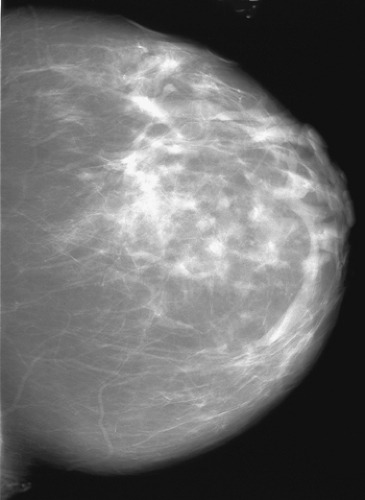

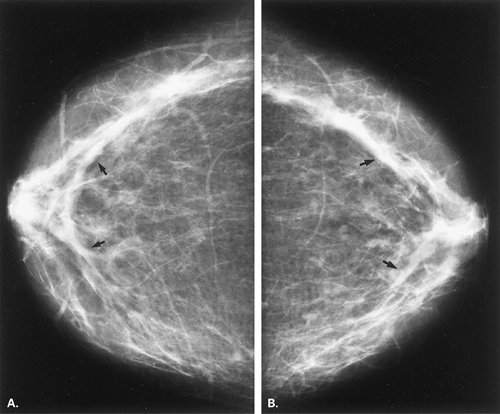

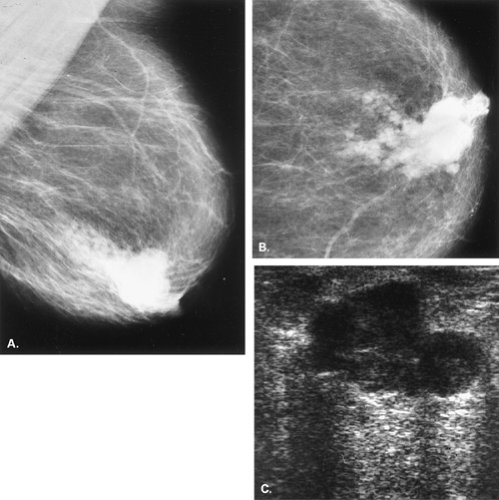

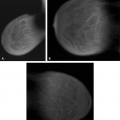

Another cause of bilateral ductal prominence is duct ectasia (Figs. 7.2,Figs. 7.3,Figs. 7.4,7.5). Haagenson (13) described the condition as beginning with bilateral dilation of the main lactiferous ducts in postmenopausal women. Amorphous debris within the ducts is irritating and causes periductal inflammation and fibrosis without epithelial proliferation. Retraction of the nipple may occur secondary to fibrosis in the periductal space. In a more recent study, Dixon et al. (14) found that periductal inflammation around nondilated ducts occurred in younger patients and that older patients had ductal dilatation as the main feature. Neither parity nor breastfeeding was found to be an important etiologic factor in this condition (14).

Dilated ductal structures may also be associated with inflammatory or infectious etiologies (Fig. 7.6). In a patient with a breast abscess or with chronic mastitis, there may be intraductal extension of the infection. This may appear as dilated ducts around an indistinct mass or as dilated subareolar ducts with overlying skin thickening. Sonography may depict the abscess cavity and the extension of fluid into ducts surrounding the cavity.

Papillomatosis

Intraductal papillomatosis is a benign lesion characterized by a papillary proliferation of the epithelium that may fill and distend the duct (15). This lesion is distinguished from a solitary intraductal papilloma. Papillomatosis tends to be scattered throughout the parenchyma and is within the

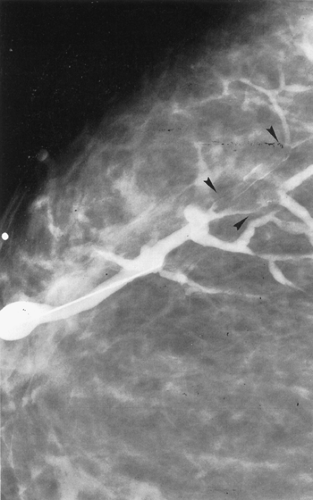

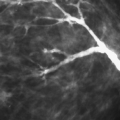

spectrum of fibrocystic change. Sometimes papillomatosis is also called intraductal hyperplasia of the common type. On mammography, the finding of a prominent ductal pattern may be evident, and fine microcalcifications are sometimes seen. On galactography, an irregular filling defect or multiple filling defects are found (Fig. 7.7).

spectrum of fibrocystic change. Sometimes papillomatosis is also called intraductal hyperplasia of the common type. On mammography, the finding of a prominent ductal pattern may be evident, and fine microcalcifications are sometimes seen. On galactography, an irregular filling defect or multiple filling defects are found (Fig. 7.7).

Papillary duct hyperplasia is an unusual lesion that occurs in children and young adults (16). Three patterns have been described: a solitary papilloma, papillomatosis, and sclerosing papillomatosis. The condition causes a distention of the duct or ducts.

Solitary or Focally Dilated Ducts

When asymmetrically dilated ducts or a solitary duct are found on mammography, the possibility of ductal malignancy must be considered. Huynh et al. (17), in a review of 46 women with asymmetrically dilated ducts, found that 24% had ductal carcinoma. Factors associated with malignancy in dilated duct patterns were the presence of associated microcalcifications, a nonsubareolar location, and interval change. The benign causes for the appearance of dilated ducts include a solitary papilloma, multiple papillomas, papillomatosis, ductal hyperplasia, and ductal adenoma.

Dilated ducts are an uncommon presentation of carcinoma but occasionally may be the only sign of this disease. A unilateral dilated duct or ducts, especially those with associated microcalcifications, are suspicious for the possibility of malignancy (18). Dilated ducts located deeper in the breast may be of greater concern for a hyperplastic or malignant lesion; a subareolar duct is more commonly seen in an intraductal papilloma (18).

Intraductal Papilloma

A solitary intraductal papilloma often presents when small and nonpalpable with a serosanguineous or bloody nipple discharge. Papillomas are usually situated beneath the nipple in a major duct; in 90% of cases, they arise within 1 cm of the nipple (19). The papilloma is connected to the duct by a thin connective tissue stalk that contains the blood supply, and it is covered by a frondlike epithelium. Because of the tenuous blood supply, these lesions tend to undergo infarction and sclerosis (20,21). When a papilloma infarcts, it may produce a bloody discharge, identified on clinical examination, and it may calcify.

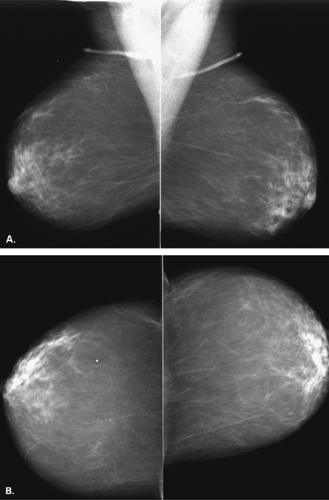

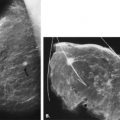

Depending on the size of the papilloma, it may not be seen on mammography, and a galactogram may be necessary to identify the location of the lesion. When papillomas are identified on the mammogram, they appear as a dilated duct or as a well-defined mass (20) (Figs. 7.8,Figs. 7.9,Figs. 7.10,Figs. 7.11,Figs. 7.12,7.13). In a study of 51 patients with solitary papillomas, Cardenosa and Eklund (22) found that 37 were symptomatic; 36 presented with spontaneous nipple discharge, and 1 had a palpable mass. Ductography was performed in 35 patients and was positive in 32. In some patients, prominent asymmetric ducts were noted at mammography, yet galactography was more useful in diagnosis by

showing a dilated duct with an intraluminal filling defect. Woods et al. (23) reviewed the clinical and imaging findings in 24 women with solitary intraductal papillomas and found that 88% presented with nipple discharge. In 42% of patients, mammography was abnormal, including showing dilated ducts in 26% of women. Galactography was successfully performed in 13 patients and showed an intraluminal defect in 12 (92%) and a duct obstruction in 1 patient.

showing a dilated duct with an intraluminal filling defect. Woods et al. (23) reviewed the clinical and imaging findings in 24 women with solitary intraductal papillomas and found that 88% presented with nipple discharge. In 42% of patients, mammography was abnormal, including showing dilated ducts in 26% of women. Galactography was successfully performed in 13 patients and showed an intraluminal defect in 12 (92%) and a duct obstruction in 1 patient.

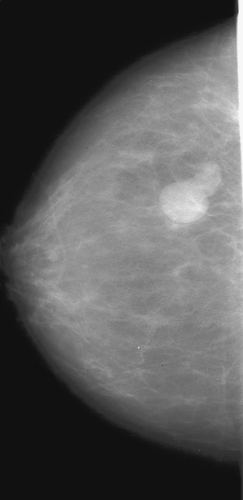

Figure 7.8 HISTORY: A 52-year-old woman for screening. MAMMOGRAPHY: Left CC view shows a lobular mass with relatively circumscribed margins located laterally. There is a tubular extension from the mass posteriorly, suggesting that this could be a dilated duct. Excisional biopsy was performed.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|