PRINCIPLES AND PRACTICE OF GERIATRIC REHABILITATION

PEARLS

❖ The purpose of geriatric rehabilitation is to assist older adults with disabilities in recovering lost physical, psychological, or social skills so that they may become more independent.

❖ Forty percent of all persons with disabilities are over age 65; the oldest-old (85 years and older) compose the highest percentage of persons with disabilities.

❖ The decline in muscle strength and mass, respiratory reserve and cardiovascular functioning, kyphotic postural changes, poorer eyesight, poor hydration and marginal nutritional intake, and many other physiological and physical changes associated with inactivity and aging lead to frailty.

❖ Three major principles influence geriatric rehabilitation. These are variability, hypokinetics, and optimal health. The influence of these can be seen in the systems of the body and should be differentiated from normal vs pathological aging.

❖ The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services interpretive guidelines define a physical restraint as “any manual method or physical or mechanical device, material, or equipment attached to or adjacent to the resident’s body, which the individual cannot remove easily, that restricts freedom of movement or normal access to one’s body.”

❖ Managing falls in older adults requires recognizing that falls are not a normal part of aging and may be due to medication, fear of falling, inactivity, chronic illness, postural instability, the use of restraints, or a combination of these.

❖ The goals for adapting an environment for the older person are to ensure safety, increase mobility, and enhance comfort and communication.

Normal aging is not necessarily burdened with disability; however, almost all conditions that cause disability are more frequently seen in the older population. As a result, older adults are more likely to require assessment for rehabilitative services. The mutual exclusion of geriatrics and rehabilitation is unjustified, and functional assessment for needed rehabilitative services should be an essential part of routine evaluation by all health care disciplines working with the older population. Geriatrics teaches that maximal functional capabilities can be attained; therefore, it can be argued that rehabilitation is the foundation of geriatric care. The purpose of this chapter is to provide clinicians with knowledge of rehabilitation principles and practices in working with the older adult and to help them apply interventions to provide high-quality care.

The basis of geriatric rehabilitation is to assist older adults with disabilities in recovering lost physical, psychological, or social skills so that they may become more independent, live in personally satisfying environments, and maintain meaningful social interactions. This may be done in any number of settings including acute and subacute care settings, rehabilitation centers, home and office settings, or long-term care facilities such as nursing homes.

Because of the complexity of the interventions needed in dealing with older adults, an interdisciplinary team approach may be required. The rehabilitation process also requires that patients and their families be educated. Finally, rehabilitation is more than a medical intervention; it is a philosophical approach that recognizes that diagnoses and chronological age are poor predictors of functional abilities, that interventions directed at enhancing function are important, and that the “team” should always include patients and their families.

DISABILITY: A DEFINITION

The meaning of disability is key to an understanding of rehabilitation. When referring to alterations in an individual’s function, 3 terms are often used interchangeably: impairment, disability, and handicap. A more distinct understanding of these concepts is useful in geriatric rehabilitation, and a “systems approach” is most useful. In the systems approach, a problem at the organ level (eg, an infarct in the right hemisphere) must be viewed in terms of not only its effects on the brain but also its effects on the person, the family, the society, and, ultimately, the nation. It goes beyond the pure “medical model,” in which only the current medical problem is assessed to determine rehabilitative goals. From this perspective, impairment refers to a loss of physical or physiological function at the organ level. This could include alterations in heart function, nerve conduction velocity, or muscle strength. Impairments usually do not affect the ability to function. However, if impairment is so severe that it inhibits the ability to function “normally,” then it becomes a disability. Rehabilitation interventions are most often oriented toward adaptation to or recovery from disabilities. Given the proper training or adaptive equipment, people with disabilities can pursue independent lives. However, obstructions in the pursuit of independence can arise when people with disabilities confront inaccessible buildings or situations that limit rehabilitation interventions, such as low toilet seats, buttons on an elevator that are too high, or signs that are not legible. In these cases, a disability becomes a handicap. Society’s environment creates the handicap.

In this chapter, we are primarily concerned with rehabilitative approaches used to reduce disabilities.

DEMOGRAPHICS OF DISABILITY IN OLDER ADULTS

Older adults are disproportionately affected by disabling conditions when compared with younger cohorts. The oldest-old age group (85 years and older) comprises the highest percentage of persons with disabilities; indeed, 40% of all persons with disabilities are over the age of 65.1 Three-fourths of all cerebrovascular accidents occur in persons over the age of 65,2–4 the highest incidence of amputations has been reported in older adults,5,6 and hip fractures occur most frequently between the ages of 70 to 78 years on average.6,7 The Federal Council on the Aging has reported that, of all those persons studied over the age of 65, 86% have at least one chronic condition, and 52% have limitations in their activities of daily living (ADLs).8 It is the impact of these disabilities on the level of independence that needs to be considered, rather than the presence of an impairment or disability.

Disabilities in old age are associated with a higher mortality rate, a decreased life span, greater chronic health problems (eg, cardiovascular, musculoskeletal, or neurologic), and an increased expenditure for health care. Disabilities resulting in an inability to ambulate, feed oneself, or manage basic ADLs, such as toileting or self-hygiene (eg, bathing), are very strong predictors of loss of functional independence and an increased burden on caregivers.9 The greater the disability, the greater the risk of institutionalization. Rehabilitative measures can be cost-effective when they enhance the patient’s functional ability and help him or her attain greater levels of independence. Higher functional capabilities and greater levels of independence have been associated with fewer hospitalizations and a lower mortality rate among older adults.10–12

Geriatric rehabilitation includes both institutional and noninstitutional services for older adults with chronic medical conditions that are marked by deviation from the normal state of health and manifested in physical impairment. Unless treated, these conditions have the potential for causing substantial, and frequently cumulative, disability. Older adults with disabilities need assistance with such daily functions as bathing, dressing, and walking. This increased need for help is often compounded when there is no spouse, nearby family, or friends able to assist the patient. With this social isolation, which is common in older adults, continuing professional medical care is required to ward off the debilitating effects of inactivity and depression.

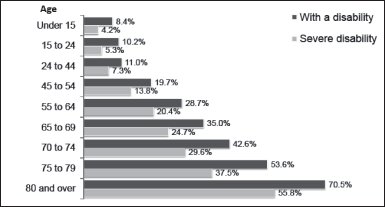

It is difficult for 32% of people over the age of 75 who live at home to climb 10 steps, 40% have difficulty walking a mile, and 22% are unable to lift 10 pounds. These percentages translate into millions of older people with some limitation in ADLs.12,13 Although dramatic gains have been made, we need to seek ways to prevent frailty and to help the oldest-old cope with ADLs. The impact of frailty is enormous in terms of costs of care in long-term care settings. Disability in older adults is not inevitable. In fact, disability rates fell during the past few decades worldwide, related to earlier rehabilitation interventions and an increased focus on prevention and healthy behaviors.13 While the general population of people 65 years and older grew by 14.7% between 2010 and 2015, the number of people with chronic disabilities or in nursing homes increased by 8.7%. This means that the proportion of people with disabilities fell, and there were hundreds of thousands fewer people with disabilities than expected.14 Figure 8-1 provides a graphic representation of the prevalence of persons with disabilities by age from 2010 US Census data. Although the rate of disability with advancing age has gone down, it is notable that disability goes up significantly in the 65 years and older age groups according to Figure 8-1.

Figure 8-1. Disability prevalence by age: 2010. (Reprinted from the US Census Bureau, Survey of Income and Program Participation, 2008 Panel, Adult and Child Functional Limitations Topical Module.)

FRAILTY: MEDICALLY COMPLEX OLDER INDIVIDUALS

Although it is difficult to concisely define the term frailty, the concept of frailty is well understood in geriatric rehabilitation. The use of the word frail conjures up a clear mental image for most clinicians. Fragile, as the root of “frailty,” implies fragility in one or more systems, leading to medical, physical, and functional instability and fluctuations. Compromises in cognition, sensorimotor input and integration,15 polypharmacy, dehydration, and malnutrition are components of frailty. Decline in muscle strength and mass,16 respiratory reserve and cardiovascular functioning, kyphotic postural changes, poorer eyesight, poor hydration and marginal nutritional intake, and many other physiological and physical changes associated with inactivity and aging lead to frailty. Any of these conditions, in isolation or in combination, can create frailty. The presence of multidiagnostic situations in older adults leads to multiple drug and nutrient interactions and complex medical management with the resulting side effects of progressive loss in functional reserve and physiological homeostasis. Concomitant diseases such as congestive heart failure, renal disease, osteoporosis, diabetes, chronic lung disease, and arthritis (to name a few) add to the level of frailty.

Impaired physical functioning has been documented in one-third of older hospitalized patients.17 With any admission for acute illness or injury in an older person, there is significant short-term deterioration in mobility and other functional domains.18 Decline in physical function, although a negative outcome in itself, has also been associated with a number of adverse consequences such as falls, disability, and mortality.12,18,19

Functional dependence develops in approximately 10% of nondisabled community-dwelling persons over the age of 75 each year.12 Increasing levels of disability are associated with substantial mortality leading to the adverse outcomes of hospitalization, nursing home placement, and greater use of home care services.19 It is estimated that it costs $14,200 for each community-living older person with disabilities annually, and at least $19 billion is spent each year on long-term care.20 Functional dependence leads to increasing levels of frailty, especially in the medically complex, multisystem-involved older adult. With each medical insult and hospitalization, there is a decreasing level of physiological capacity associated with difficulty in recovery to premorbid functional abilities.20,21 Movement of frail older people through the health care system is relevant for clinicians. Cost-containment strategies that encourage providers to substitute less costly care in the community for the more expensive care in hospitals and nursing homes may have implications for the patient’s functioning, ability to remain at home, or other treatment outcomes.19,21 An understanding of this issue is essential to ensure that frail older patients receive the services they need and are treated appropriately.

Mrs. K., a 78-year-old woman who lived alone and independently, became frail because of the complacency of preventive and medical interventions and the limitations in the reimbursement system. Diagnosed with worsening arthritis and osteoporosis, she fell and broke her hip. Following surgery, rehabilitation was only partially successful when she was discharged from this service due to a lack of insurance coverage and sent home. After a second fall, she entered a nursing home and became depressed. Antidepressant drugs made her lightheaded and dizzy. She fell again, breaking her other hip. She was unable to participate in rehabilitation due to confusion and medical complications, and she became bedridden. Unfortunately, this is not an atypical rehabilitation scenario. Mrs. K.’s progressive frailty might have been prevented or reversed at several points. One such point might have been from a preventive perspective, before she developed osteoporosis, which can be prevented or at least alleviated through exercise, nutrition, and, in some cases, hormone replacement therapy. Mrs. K.’s first fall could have been prevented with simple and practical measures, such as muscle-strengthening exercises, balance training, protective ambulatory devices, and environmental assessment and modification for safety.

FUNCTIONAL ASSESSMENT OF OLDER ADULTS

The assessment of functional capabilities is the cornerstone of geriatric rehabilitation. The ability to walk, to transfer (eg, from bed to chair or chair to toilet), and to manage basic ADLs independently is often the determinant of whether hospitalized older patients will be discharged home or to an extended care facility. Functional assessment tools, which are practical, reliable, and valid, are necessary to assist all interdisciplinary team members in determining the need for rehabilitation or long-term care services. In the home care setting, precise assessment of a patient’s function can detect early deterioration and allow for immediate intervention. (See Chapter 10 for specific information on functional assessment tools.)

FUNCTIONAL ABILITIES OF THE CAREGIVER: A REHABILITATIVE CONSIDERATION

Given a choice, older patients would prefer to stay at home rather than recuperate and rehabilitate in an institutional setting. Older adults have strong ties to their homes, and the help of their spouses, other relatives, and friends is a crucial component in making rehabilitation in their homes possible. Home care by professionals can protect the health of informal caregivers and maximize the patient’s ability to perform ADLs by including a systematic assessment of the living environment as a key part of care planning. The provision of such assistance openly acknowledges that caregivers (often older themselves) have some decrease in physical ability that needs to be considered as it relates to caring for relatives with disabilities. It has been demonstrated that over 90% of persons 75 to 84 years of age can manage without help to perform such tasks as grooming, bathing, dressing, and eating.22 The more complicated skills of transferring and ambulation are more compromised, with over 50% of persons 75 to 84 years of age presenting with limitations in their capabilities of performing these activities without assistance. These ADLs require greater assistive skills on the part of the caregiver. Assessment of the home environment needs to incorporate the abilities (or disabilities) of the individual(s) providing care. Adaptive equipment, such as a sliding board for transfers or a rolling walker for ambulation, is available to assist the caregiver in caring for his or her spouse, relative, or friend. Attention to the abilities of the caregiver can facilitate the ease of care and decrease the burden placed on the caregiver. The provision of home health care services may be necessitated when safety is an issue. Thorough evaluation of the functional capabilities of the older adult and the caregiver, in addition to assessment of the environmental obstacles that may be encountered, will increase the likelihood of a positive outcome.

PRINCIPLES OF GERIATRIC REHABILITATION

Three major principles are important in the rehabilitation of older adults. First, the variability of older adults must be considered. The variability of capabilities within an older group is much more pronounced than within younger cohorts. What one 80-year-old person can do physically, cognitively, or motivationally, another may not be able to accomplish. Second, the concept of activity is key in rehabilitation of older adults. Many of the changes over time are attributable to disuse. Finally, optimum health is directly related to optimum functional ability. In acute situations, rehabilitation must be directed toward (1) stabilizing the primary problem(s); (2) preventing secondary complications such as bedsores, pneumonias, and contractures; and (3) restoring lost functions. In chronic situations, rehabilitation is directed primarily toward restoring lost functions. This can best be accomplished by promoting maximum health so that older adults are best able to adapt to their care environment and to their disabilities. Each of these principles—variability, inactivity, and optimum health—are discussed in greater detail in the following sections.

Variability of Older Adults

Unlike any other age group, older adults are more variable in their level of functional capabilities. In the clinic, we often see 65-year-old individuals with severe physical disabilities, yet sitting right alongside of that individual is a 65-year-old who is still building houses and felling trees. Even in the oldest-old, the variability in physical and cognitive functioning is remarkable. For example, at one end of the spectrum is John Kelly, who, at the age of 87, was still running the Boston Marathon, while at the other end of the spectrum is a frail bedridden 87-year-old person in a nursing home who is not responsive to his or her environment. The differences can also be identified cognitively and are just as remarkable. The spectrum moves from the demented, institutionalized aged to those aged who are presidents and Supreme Court justices. Chronological age is a poor indicator of physical or cognitive function.

The impact of this variability is an important consideration in defining rehabilitation principles and practices of older adults. A wide range of rehabilitative services must be provided to address the varying needs of the older population in different care settings. Awareness of this heterogeneity helps to combat the myths and stereotypes of aging and presents a foundation for developing creative rehabilitation programs for older adults. Older persons tend to be more different from themselves (as a collective group) than other segments of the population. Given this fact, interdisciplinary team members, policy makers, and planners in rehabilitation settings need to be prepared to design a wide range of services and treatment interventions. This becomes more difficult as the number of older adults increases and the budget decreases; however, creating new and innovative rehabilitation programs could ultimately improve the functional capabilities and the resulting quality of life for many older individuals.

Activity Versus Inactivity

The most common reason for losses in functional capabilities in older adults is inactivity or immobility. There are numerous reasons for immobilizing older adults. Acute immobilization is often considered to be accidental immobilization. Acute catastrophic illnesses include severe blood loss, trauma, head injury, cerebrovascular accidents, burns, and hip fractures, to name only a few. The patient’s activity level is often severely curtailed until acute illnesses become medically stable. Chronic immobilization may result from long-standing problems that are undertreated or left untreated. Examples of chronic problems include cerebrovascular accidents (strokes), amputations, arthritis, Parkinson disease, cardiac disease, pulmonary disease, and low back pain. Environmental barriers are a major cause of accidental immobilization in both the acute and chronic care settings. These include bed rails, the height of the bed, physical restraints, an inappropriate chair, no physical assistance available, fall precautions imposed by medical staff, no orders in the chart for mobilization, social isolation, and environmental obstacles (eg, stairs or doorway thresholds). Cognitive impairments, central nervous system disorders (such as cerebrovascular accidents, Parkinson disease, and multiple sclerosis), peripheral neuropathies resulting from diabetes, and pain with movement can also severely reduce mobility. Affective disorders such as depression, anxiety, or fear of falling may also lead to accidental immobilization. In addition, sensory changes, terminal illnesses (such as cancer or cirrhosis of the liver), acute episodes of illness like pneumonia or cellulitis, or an attitude of “I’m too sick to get up” can negatively affect mobility.

The process of deconditioning involves changes in multiple organ systems, including the neurologic, cardiovascular, and musculoskeletal systems to varying degrees. Deconditioning is probably best defined as the multiple changes in organ system physiology that are induced by inactivity and reversed by activity (eg, exercise).16,23 The degree of deconditioning depends on the degree of superimposed inactivity and the prior level of physical fitness. The term hypokinetics has been coined to describe the physiology of inactivity.24 Deconditioning can occur at many levels of inactivity. For simplicity and clarity, 2 major categories of inactivity or hypokinetics are examined: the acute hypokinetic effects of bed rest and the chronic inactivity induced by a sedentary lifestyle or chronic disease.

Looking at the aging process with one eye on the adverse effects of bed rest or hypokinetics as a possible concomitant of deconditioning and disability can lead to discovering more about the potential use of exercise as one of our primary rehabilitation modalities. The phrase “use it or lose it” is a concept with tremendous ramifications for aging, especially in geriatric rehabilitation. Exercise has not been viewed as an important factor in health until recently. Until the 1950s, the rate of living theory was promoted. According to this theory, the body would be worn out faster and life shortened by expending energy during exercise.25 Conversely, studies in the past decade have shown that regular exercise does not shorten life span and may in fact increase it.26 Exercise is increasingly viewed as beneficial for both the primary and secondary prevention of disease.27

There are several challenges to understanding the interaction between inactivity and health in older persons. The first is that the process of aging itself causes some changes that parallel the consequences of hypokinetics or inactivity. Several studies have provided strong evidence that separates the aging process from a sedentary lifestyle.28–43 It has been found that older individuals can improve their flexibility, strength, and aerobic capacity to the same extent as younger individuals. The second challenge in studying inactivity is separating the effects of inactivity from those of disease.36,37 It is obvious that some effects of aging can be directly related to inactivity. Many older individuals who are deconditioned may also have superimposition of acute or chronic disease. Studies on younger individuals have helped to clarify some of the effects of inactivity alone (eg, bed rest on physiological changes and functional performance).

Another challenge exists—the challenge of understanding the relationship between physiological decline and functional loss. Is the inability to climb stairs in an 85-yearold individual primarily from cardiovascular deconditioning, muscle weakness, impaired balance secondary to sensory losses, or a sedentary lifestyle? Is there a new disease process beginning? Is this normal aging? An important concept in geriatric rehabilitation is that threshold values of physiological functioning may exist.27,31 An older person who is below these thresholds may suddenly lose an essential functional skill. An understanding of the consequences of inactivity is particularly important in addressing rehabilitation needs of the older adult. Table 8-1 summarizes the complications of bed rest.

The evaluation and treatment of hypokinetics are crucial in the total care of older adults. Passive range of motion or active assistive range of motion is appropriate even in the most immobilized patients to prevent the consequences of immobilization. Aging and inactivity are both associated with a loss of lean body mass and a gain in body fat.31,34 Some degree of changes associated with aging is directly related to inactivity. Active older individuals show lesser degrees of these changes, and exercise programs in sedentary older persons have been shown to positively modify those changes associated with aging. Exercise has been shown to reverse the physiological changes of inactivity including a return of cardiovascular and cardiopulmonary response to pre–bed rest base lines and a return of muscle strength and flexibility.27 The following mnemonic representation of the effects of bed rest is helpful in remembering the overall effects of inactivity on functional capabilities:

❖ B—Bladder and bowel incontinence and retention, bed sores, brain changes, behavior

❖ E—Emotional trauma, electrolyte imbalances, exercise intolerance

❖ D—Deconditioning, depression, demineralization of bones, disability

❖ R—Range of motion (loss/contractures), restlessness, renal dysfunction

❖ E—Energy depletion, electroencephalographic irregularity, endocrine imbalances

❖ S—Sensory deprivation, sleep disorders, skin problems

❖ T—Trouble with ALL systems

Older adults are especially susceptible to the complications of bed rest. Aging changes and common chronic diseases result in a decrease in physiological reserve and a decreased ability to tolerate the changes that occur with bed rest. The physiology of aging and bed rest have many features in common and may be additive in their effects. The changes that commonly occur with aging and prolonged bed rest independently lead to osteoporosis, decreased endurance, and impaired mobility and increase the predisposition to falls, deep venous thrombosis, sensory deprivation, and pressure sores.

With the numerous adverse effects of bed rest, it should be prescribed judiciously and with full awareness of its potential complications and the need for preventive exercise prescription. Any older patient on bed rest should be on a physical or occupational therapy program. When full activity is not possible, limited activity such as movement in bed, ADLs, and intermittent sitting and standing will reduce the frequency of some complications of bed rest. Prolonged bed rest causes significant cardiovascular, respiratory, musculoskeletal, and neuropsychological changes. Complications are often irreversible. Complete bed rest should be avoided at all costs.

Optimal Health

The last principle in geriatric rehabilitation is the principle of optimal health. The great English statesman Benjamin Disraeli said, “The health of people is really the foundation upon which all their happiness and their powers as a state depend.” In the early 1960s, the World Health Organization defined health as a state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being, not merely the absence of disease or infirmity.44 The existence of complete physical health refers to the absence of pathology, impairment, or disability. Physical health is quite achievable. Mental and social well-being are closely related and possibly less obtainable in this day and age. Mental health as defined by the World Health Organization would include cognitive and intellectual intactness as well as emotional well-being. The social components of health would include living situation, social roles (ie, mother, daughter, vocation, etc), and economic status.

There are some cumulative effects—biological, physiological, and anatomical—that may eventually lead to clinical symptoms. It has also been noted in this chapter that some of these changes are associated with inactivity and not purely a result of progressive aging effects. In light of this, a preventive approach to physical health needs to be in the foreground when addressing the needs of older adults.

Preventing impairment and disability is a key principle in geriatric rehabilitation. It is reasonable to assume that the health status of individuals in their 70s and subsequent decades of life is in a suboptimal range. Thus, the scope of health status for older adults should be focused toward preventing the complications that could result from suboptimal health. When considering suboptimal health then, the goal of geriatric rehabilitation should be to strive for relative optimal health (ie, the maximal functional and physical capabilities of the older adult considering his or her current health status).

In reviewing the importance of promoting relative optimal health in terms of the musculoskeletal, sensory, or cardiopulmonary systems, an example of an older woman with a hip fracture may help.

The patient may be in suboptimal health and suffering from osteoporosis; however, she is not treated until she fractures her hip. The resulting complications could include pneumonia, decubiti from bed rest, all of the changes previously noted in relation to inactivity, and the possibility of death. Intervention at the suboptimal level was needed here rather than waiting for an illness or disability to occur. This intervention could include weightbearing exercises to enhance the strength of the bone, strengthening exercises of the lower extremities to provide adequate stability and endurance, balance and postural exercises to facilitate effective balance reactions and safety, education in nutrition, and modification of her living environment to ensure added safety in hopes of avoiding the kind of fall that results in a hip fracture.

Another excellent example of preventive intervention to maintain optimal health would be in the case of the older adult with diabetes. It is known that sensory loss in the lower extremities resulting from diabetes mellitus often predisposes individuals with diabetes to ulceration of the foot. An ill-fitting shoe or a wrinkle in the sock may go unnoticed and lead to friction, skin breakdown, and a resulting foot ulcer. If undetected, even the smallest ulcer may lead to amputation of a lower extremity. Screening of the foot during evaluation can prevent this devastating loss. Intervention could include education of the older adult in foot inspection (or education of a family member or friend if the eyesight of the older adult with diabetes is compromised), proper shoe fitting, and techniques for dealing with sensory loss (eg, as temperature sensation diminishes, the individual needs to test bath water temperature with a thermometer or have one’s spouse test the water before putting his or her insensitive feet into a steamy bath). With proper skin care and professional (podiatric) care of the nails and calluses, there is less likelihood that injury will occur. The cost of a therapeutic diabetic shoe (eg, the PW Minor Thermold shoe) is $130 to $160 per pair, and this shoe provides protection and ample room for the forefoot. Compare this to the cost of ulcer care, which averages $6000, and the cost of hospitalization and rehabilitation for amputation, which averages $30,000.45

The principle of obtaining relative optimal health in geriatric rehabilitation is not only cost-effective but also would clearly lead to an overall improvement in the quality of life. Encouraging healthy behaviors, such as decreasing obesity, stress, and smoking and increasing activity, could be the element necessary in maintaining health and striving for optimal health as defined by the World Health Organization.44

Health care professionals involved in geriatric rehabilitation need to be good evaluators and screeners. Good investigative skills could detect a minor problem with the potential of developing into a major problem. Thorough assessment of physical, cognitive, and social needs could help us to modify rehabilitation programs accordingly to truly improve the health and functional ability of our older clients.

REHABILITATIVE MEASURES

Rehabilitation should be directed at preventing premature disability. A deconditioned older individual is less capable of performing activities than a conditioned older individual. For example, the speed of walking is positively correlated to the level of physical fitness in an older person.46 When cardiovascular capabilities are diminished (ie, maximum aerobic capacity), walking speeds are adjusted by the older person to levels of comfort. Exercise programs geared for improving cardiovascular fitness also have the benefits of improving the speed of walking.46 The more conditioned the individual, the faster the walking pace. The faster the walking pace, the smoother the momentum, decreasing the likelihood of falling. The better-conditioned older adult is also more agile and has improved reaction times to balance perturbation when compared to an unfit older individual. Since this early research, a subsequent study has determined that walking speed is a functional vital sign that predicts frailty in older adults.47 Walking speed has been determined to be a valid, reliable, and sensitive measure appropriate for assessing and monitoring functional status and overall health in a wide range of populations. These capabilities have led to its designation as the “sixth vital sign.”47

If disease and physical disability are superimposed in hypokinetic sequelae, the functional consequences can be disastrous because pain often prevents mobility. For instance, the pain experienced by an older individual with an acute exacerbation of osteoarthritic knee pain accompanied by inflammation of the knee capsule may reflexively inhibit quadriceps contraction. Although strength of the quadriceps may have been poor in the first place due to inactivity, the absence of pain still permitted this individual to rise from a chair or ascend shallow steps. Now, with the presence of acute pain, these activities cause severe discomfort and threaten the capability of maintaining an independent lifestyle. In this situation, rehabilitation efforts should focus medically on the following:

❖ Reducing the inflammation through drugs or ice (physician or nurse)

❖ Maintaining joint mobility during the acute phases by joint mobilization techniques of oscillation and low-grade passive range of motion in addition to modalities, such as interferential current, to assist in reducing the edema and decreasing the discomfort (physical therapy)

❖ Joint protection techniques and prescription of adaptive equipment such as a walker to protect the joint (occupational and physical therapy)

❖ Provision for proper nutrition in light of medications/nutrient (pharmacist/dietician) effects and evidence that vitamin C is a crucial component in the health of the synovium48

❖ Social and psychological support (social worker, psychologist, or religious personnel) to provide emotional and motivational support

These interventions to prevent the debilitating effects of bed rest highlight the need for an interdisciplinary approach when addressing geriatric rehabilitation.

Rehabilitation of the older adult should emphasize functional activity to maintain functional mobility and capability, improvement of balance through exercise and functional activity programs (eg, weight shifting exercises, ambulation with direction and elevation changes, and reaching activities), good nutrition and good general care (including hygiene, hydration, bowel and bladder considerations, and appropriate rest and sleep), and social and emotional support.

It is important to optimize overall health status by implementing the concept of independence. The more an individual does for him- or herself, the more he or she is capable of doing independently. The more that is done for an older individual, the less capable that person becomes of functioning on an optimal independent level and the more likely the progression of a disability.

Health Awareness and Beliefs

The advancing stages of disabilities increase an individual’s vulnerability to illness, emotional stress, and injury. An older person’s subjective appraisal of personal health status influences how he or she reacts to the symptoms, perceives his or her vulnerability, and perceives his or her abilities to perform a given activity. Often an older person’s self-appraisal of health is a good predictor to the rehabilitation clinician’s evaluation of health and functional status, but such assessments may also differ in many ways. In older persons, perceptions of one’s health may be determined in large part by one’s level of psychological well-being and by whether or not one continues in rewarding roles and activities.49

Because an older individual’s perception of his or her health status is an important motivator in compliance with a rehabilitation program, it is important to discuss this further. One interesting study showed that even when age, sex, and health status (as evaluated by physicians) were controlled for, perceived health and mortality from heart disease were strongly related.49 Those who rated their health as poor were 2 to 3 times as likely to die as those who rated their health as excellent. A Canadian longitudinal study of persons over 65 years old produced similar results.50 Over 3 years, the mortality of those who described their health as poor at the beginning of the study was about 3 times that of those who initially described their health as good.

Yet, despite this apparent awareness among older persons of their actual state of health, older adults are known to fail to report serious symptoms and wait longer than younger persons to seek help. Rehabilitation professionals need to listen carefully to their older clients with this in mind. It appears that, contrary to the popular view that older individuals are somewhat hypochondriacal, older persons generally deserve serious attention when they bring complaints to their caregivers.

The perceived level of health will greatly impact the outcomes of functional goals in the geriatric rehabilitation setting, whether it is acute, rehabilitative, home, or chronic care. Improvement in rehabilitation tasks correlates well with patients’ appraisal of their potential for recovery but not very well with others’ appraisal.51 Stoedefalke52 reported that positive reinforcement (frequent positive feedback) for older persons in rehabilitation greatly improved their performance and feelings of success. This indicates that older persons can improve in their physical functioning when modifications in therapeutic interventions provide feedback more often. Some research indicates that older persons with chronic illness have low initial aspirations with regard to their ability to perform various tasks; yet through positive reinforcement and favorable task results, an activity/exercise program can be sustained.53 As situations in which individuals succeeded or failed, their aspirations and motivation changed to more closely reflect their abilities.

Older persons may have different beliefs about their abilities compared to younger persons.54 When participants were given an unsolvable problem, younger participants ascribed their failure to not trying hard enough, whereas older participants ascribed their failure to inability. On subsequent tests, younger participants tried harder, and older participants gave up. This holds extreme importance in the rehabilitation potential of an older person. If the person sees the cause of failure as an immutable characteristic, then little effort in the future can be expected.

Older individuals may have a higher anxiety level in rehabilitation situations because they fear failure or are afraid of “looking bad” to their family or therapist.55 If anxiety is high enough, then the behavior is redirected toward reducing the anxiety rather than accomplishing the task.55 Persons allowed to set their own goals for task achievement, even if they are directed to adopt the therapist’s goals, have been shown to experience more favorable outcomes.56 Other research found that the best performance at difficult tasks, as many rehabilitation tasks are, occurs when the older person sets a very specific goal, such as walking 10 feet with a walker.57 If the person simply tries to “do better,” then performance is not improved as much. These are important motivational components to keep in mind when working with an older client. Perhaps the therapeutic approach of the clinician may have the greatest impact on the successful functional outcomes in a geriatric rehabilitation setting.

Exercise Programming

Exercise programs have potential for improving physical fitness, agility, and speed of response.31 They also serve to improve muscle strength, flexibility, bone health, cardiovascular and respiratory response, and tolerance to activity.58 Evidence suggests that reaction time is better in older adults who engage in physical exercise than in those who are sedentary.59 Stelmach and Worringham59 showed a positive correlation between individuals’ ability to maintain their balance when stressed and their level of fitness. Initial test scores on reaction time were significantly improved following a 6-week stretching and calisthenics program in individuals 65 years and older. This has great clinical significance when considering the increasing incidence of falls with age (an area to be discussed in more detail in a subsequent section of this chapter).

In addition, exercise has been shown to provide social and psychological benefits affecting the quality of life and the sense of well-being in older adults.60 Intuitively, it would appear plausible that an older individual who is in better physical condition will experience less functional decline and maintain a higher level of independence and a resulting improvement in his or her perceived quality of life. The risks of encouraging physical activity are small and can be minimized through careful evaluation. Although all of the exercise and activity programs that constitute therapeutic exercise cannot be described in detail in this chapter, Table 8-2 summarizes therapies for various conditions seen most frequently in geriatric rehabilitation settings.

Specialized exercise techniques, such as proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation, Bobath, and contemporary motor control and sensory integration techniques, are very useful in regaining and maintaining functional mobility and strength and improving sensory awareness in older individuals.61 Although these therapeutic exercises vary in application techniques, the concept of integrating sensory and motor function is consistent in each.

These exercise techniques are methods of placing specific demands on the sensory motor system in order to obtain a desired response. By definition, facilitation implies the promotion or hastening of any natural process—the reverse of inhibition, specifically, the effect produced in nerve cells by the introduction of an impulse. Thus, these techniques, although highly complex and requiring specialized training to use, may simply be defined as methods of promoting or hastening the response of the neuromuscular mechanism through stimulation of the proprioceptors.62

The normal neuromuscular mechanism is capable of a wide range of motor activities within the limits of the anatomical structure, the developmental level, and inherent and previously learned neuromuscular responses. The normal neuromuscular mechanism becomes integrated and efficient without awareness of individual muscle action, reflex activity, and a multitude of other neurophysiological reactions. Variations occur in relation to coordination, strength, rate of movement, and endurance, but these variations do not prevent adequate response to the ordinary demands of life.

The deficient neuromuscular mechanism is inadequate to meet the demands of life in proportion to the degree of the deficiency. Responses may be limited in older persons by the faulty neuromuscular response previously discussed as sequelae of the aging process, inactivity, trauma, or disease of the nervous or musculoskeletal system.

Table 8-2. Rehabilitation Therapies for Common Conditions

CEREBROVASCULAR ACCIDENT (STROKE)

Physical Therapy

- Pregait activities (if individual is not ambulatory)

- Gait/balance training (if individual is ambulatory)

- Provision of assistive ambulatory devices (quad cane, hemi walker)

- Ambulation on different types of surfaces (stairs, ramps)

- Provision of appropriate shoe gear and orthotics

- Education and provision of appropriate bracing

- Range of motion, strengthening, coordination exercises

- Proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation

- Bobath techniques to modify tone

- Sensory integration

- Joint mobilization techniques (when appropriate)

- Functional electrical stimulation (when appropriate)

- Positioning and posturing (chair, feeding needs)

- Family and patient education for home management

- Alternative interventions—Feldenkrais, qigong, tai chi, yoga

Occupational Therapy

- Training in activities of daily living (grooming, dressing, cooking, etc)

- Transfer training (toilet, bathtub, car, etc)

- Activities and exercise to enhance function of upper extremities

- Training to compensate for visual-perceptual problems

- Provision of adaptive devices ( reachers, special eating utensils)

Speech Therapy

- Language production work

- Reading, writing, and math retraining

- Functional skills practice (checkbook balancing, making change)

- Therapy for swallowing disorders

- Oral muscular strengthening

PARKINSON DISEASE

Physical Therapy

- Gait training

- Provision for appropriate shoe gear and orthotics

- Training in position changes

- General conditioning, strengthening, coordination, and range of motion exercises

- Breathing exercises

- Training in functional instrumental activities of daily living

- Proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation/sensory integration

- Alternative interventions—aquatic therapy, Feldenkrais, qigong, tai chi

Occupational Therapy

- Fine/gross motor coordination of upper extremities

- Provision of adaptive equipment

- Basic self-care activity training

- Transfer training

Speech Therapy

- Improving respiratory control

- Improving coordination between speech and respiration

- Improving control of rate of speech

- Use of voice amplifiers and/or alternate communication devices

ARTHRITIS

Physical Therapy

- Joint protection techniques

- Joint mobilization for pain control and mobility

- Conditioning, strengthening, and range of motion exercises

- Gait training

- Provision of proper shoe gear and orthotics

- Modalities to decrease pain and edema and break up adhesions

- Provision of assistive ambulatory devices (when appropriate)

- Alternative interventions—aquatic therapy, Feldenkrais, qigong, tai chi, yoga

- Refer for nutritional counseling

Occupational Therapy

- Range of motion and strengthening exercise of upper extremities

- Splinting to protect involved joints, decrease inflammation, and prevent deformity

- Joint protection techniques

- Provision of adaptive devices to promote independence and avoid undue stress on involved joints

AMPUTEES

Physical Therapy

- Fitting and provision of temporary and permanent prosthetic devices

- Teaching donning and doffing of prostheses

- Progressive ambulation

- Provision of assistive ambulatory devices

- Training in stump care

- Wound care (when appropriate)

- Provision of shoe gear and protective orthotic for uninvolved extremity

- Instruction in range of motion, strengthening, and endurance activities for both involved and uninvolved extremities

- Balance activities

- Transfer training

- Patient education in skin care and monitoring

- Alternative therapies—Feldenkrais, qigong, yoga

- Refer for nutritional counseling

Occupational Therapy

- Teaching donning and doffing of prostheses

- Training in stump care

- Transfer training

- Training in activities of daily living

CARDIAC DISEASE

Physical Therapy

- Patient education

- Conditioning and endurance exercises (walking, biking, etc)

- Breathing and relaxation exercises

- Strengthening and flexibility exercises

- Monitoring of patients’ vital signs during exercise

- Stress management techniques

- Alternative interventions—qigong, tai chi, yoga

- Refer for nutritional counseling

Occupational Therapy

- Labor-saving techniques

- Improving overall endurance for participation in activities of daily living

- Monitoring patients’ participation in activities of daily living

PULMONARY DISEASE

Physical Therapy

- Patient education

- Breathing control exercises

- Chest physical therapy

- Conditioning exercises

- Joint mobilization of rib cage

- Relaxation and stress management techniques

- Alternative interventions that incorporate controlled breathing patterns—Feldenkrais, qigong, tai chi, yoga

Occupational Therapy

- Training in labor-saving techniques

- Monitoring of participation in activities of daily living

- Improving endurance of upper extremities

LOW BACK PAIN

Physical Therapy

- Joint mobilization/stabilization

- Modalities to decrease pain and improve tissue mobility

- Strengthening and flexibility exercises

- Instruction in proper body mechanics for lifting, sitting, and sleeping

- Provision of proper shoe gear and shock-absorbing orthotics

- Correction of leg length discrepancy (when appropriate)

- Postural training for positioning

- Relaxation and stress management techniques

- Alternative approaches to encourage posture—Feldenkrais, qigong, tai chi, yoga

Occupational Therapy

- Training in ergonomic techniques

- Training in energy conservation and positioning at rest

ALZHEIMER DISEASE

Physical Therapy

- Sensory integration techniques

- Gait training (when appropriate)

- Balance activities

- Provision of proper shoe gear and orthotics

- General conditioning exercises

- Reality orientation activities/validation techniques

- Alternative interventions—dancing, hammock, qigong, tai chi

Occupational Therapy

- Sensory integration techniques

- Activities of daily living (grooming, feeding, etc)

- Reality orientation activities/validation techniques

HIP FRACTURES

Physical Therapy

- Range of motion, strengthening, and conditioning exercises

- Positioning

- Progressive weightbearing and gait training

- Provision of assistive ambulation devices

- Provision of proper shoe gear, lift on the involved side, and orthotics for shock absorption

- Balance activities

- Transfer training

- Referral to nutritionist if presence of osteoporosis

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree