Preneoplastic Conditions of the Endometrium: Endometrial Hyperplasia, the Emergent Concept of Endometrial Intraepithelial Neoplasia, and Others

Anais Malpica MD

In this chapter, the preneoplastic conditions of the endometrium are reviewed. The traditional approach to the preneoplastic condition of endometrioid adenocarcinoma, which is known as endometrial hyperplasia, and the more recently proposed approach, which is designated as endometrial intraepithelial neoplasia, are included. In addition, conditions that are commonly associated with endometrial hyperplasia, the metaplasias, are presented.

ENDOMETRIAL HYPERPLASIA

Endometrial hyperplasia has been the term traditionally used to designate an endometrial proliferation where there is a predominance of endometrial glands over endometrial stroma. This is the most widely accepted approach to the endometrial, endometrioid type of preneoplastic condition. Table 3-1 summarizes the World Health Organization (WHO) classification1 of endometrial hyperplasia.

The WHO classification is based entirely on histologic features as follows: (1) a shift in the gland-to-stroma ratio with architectural alteration and (2) the presence or absence of cytologic atypia in the epithelium lining the proliferating glands. It is important to bear in mind that although the hyperplastic endometrium is usually increased in volume, in some cases, the hyperplasia is just a focal finding in an otherwise nonhyperplastic endometrium.2

Tble 3-1 World Health Organization (WHO) Classification of Endometrial Hyperplasia | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||

Shift of the Gland-to-Stroma Ratio with Architectural Alteration

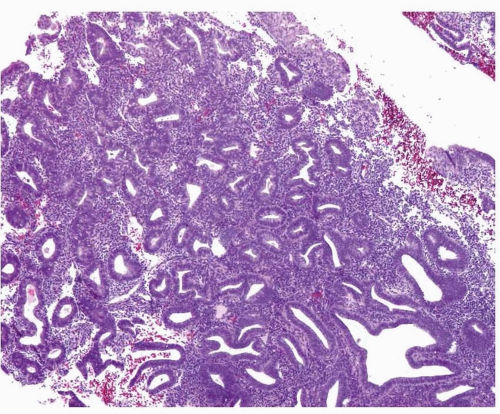

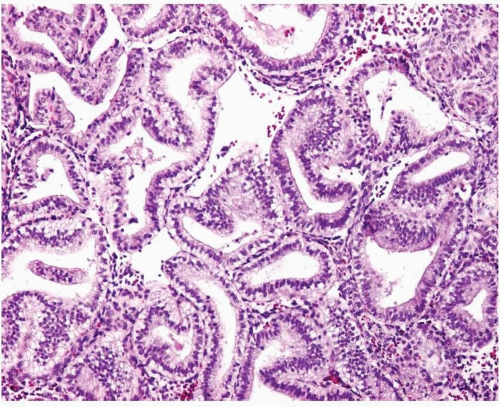

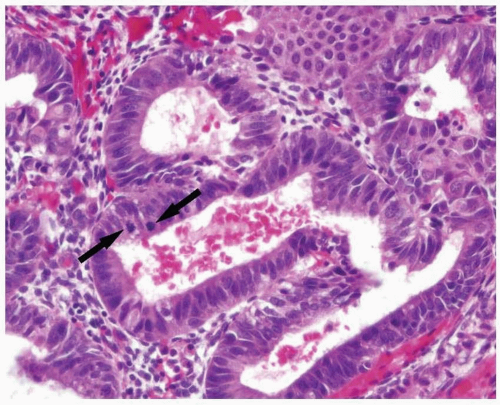

Although the WHO classification does not provide a threshold to determine what constitutes a shift in the gland-to-stroma ratio, in our practice, we follow the recommendation provided by Hendrickson et al.3 Essentially, endometrial hyperplasia is diagnosed when the glandular proliferation is sufficient to shift the gland-to-stroma ratio from 2:1 to 3:1 (i.e., the endometrial stroma representing less than one-half to one-third of the cross-sectional area of the proliferation) (Fig. 3-1). Both glands and villoglandular structures are included in the glandular component. The hyperplastic glands usually have proliferative features (i.e., pseudostratification and mitotic activity) (Fig. 3-2), except in the uncommon cases of hyperplasia with secretory changes (Fig. 3-3).

FIGURE 3-2: Endometrial epithelium usually demonstrates proliferative features such as pseudostratification and mitoses (arrows). |

Simple versus Complex Endometrial Hyperplasia

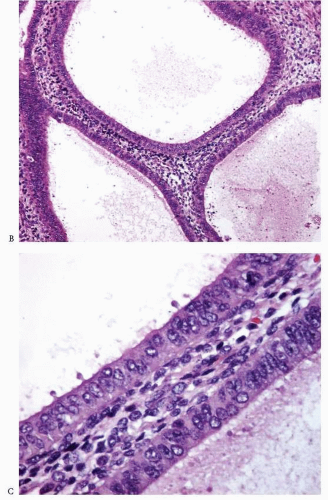

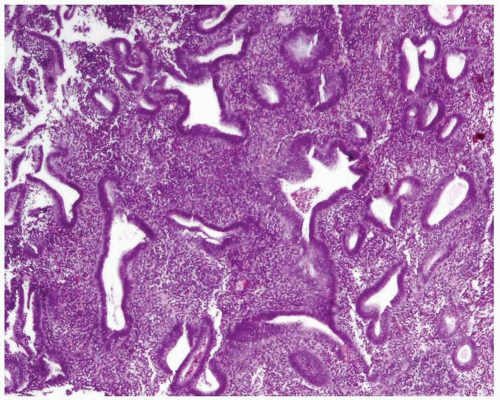

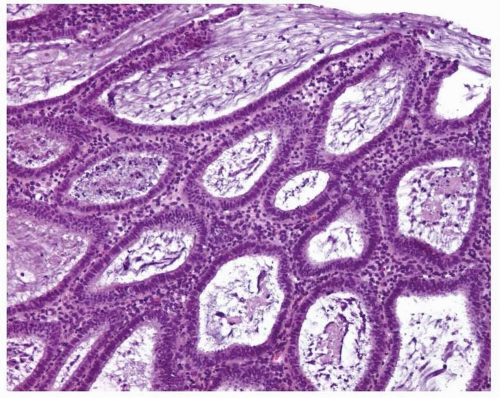

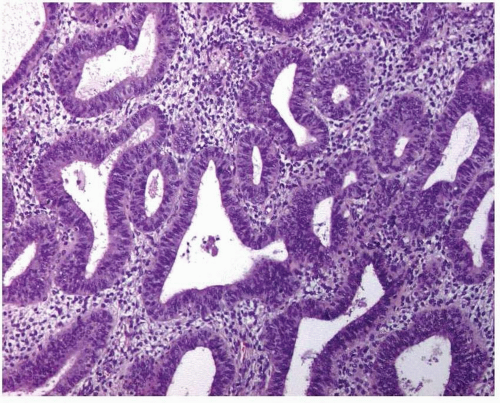

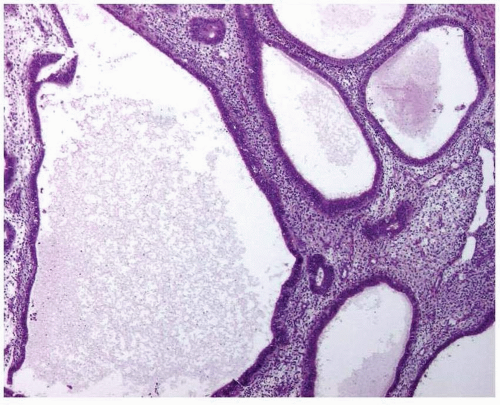

Simple endometrial hyperplasia is characterized by a proliferation of dilated endometrial glands of variable size, with no or slight outpouchings (Fig. 3-4), whereas in complex endometrial hyperplasia, the endometrial glands are markedly irregular in size and shape with numerous outpouchings (Fig. 3-5).

Diagnosis of Atypia

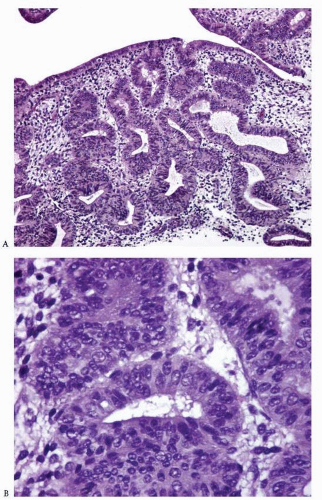

Atypia of the endometrial epithelium lining the proliferating glands is characterized by nuclear enlargement, round rather than oval nuclei, irregular distribution of the chromatin, and a variable presence of conspicuous nucleoli4 (Figs. 3-6 and 3-7). While assessing the presence of atypia, several issues should be considered.

Artifactual Changes Secondary to Variations in Tissue Fixation and Processing

Variations in tissue fixation and processing can induce changes in the appearance of the nuclei, including alterations in the chromatin distribution and the presence of nucleoli. To prevent any misinterpretation while trying to determine whether cytologic atypia is present, it is necessary to obtain a reference point for each case by examining the nuclear features of the endometrial glands in areas without hyperplasia.

FIGURE 3-4: Simple hyperplasia. Note the proliferation of dilated endometrial glands with no or slight outpouchings. |

FIGURE 3-5: Complex hyperplasia. Note the proliferation of endometrial glands of variable size and shape with outpouchings. |

FIGURE 3-6: Simple hyperplasia with atypia (A). Note the nuclear enlargement, round nuclei, irregular distribution of the chromatin, and variable presence of nucleoli (B and C). (continued) |

Metaplastic Changes

Nuclear changes typically seen in the endometrial glands undergoing metaplastic changes can be misinterpreted as atypia. For example, in ciliated or eosinophilic cell metaplasia, the nuclei can be enlarged and rounded; however, the chromatin distribution is uniform, and the nuclear contour is regular.

Extent and Degree of Atypia: What Is Relevant?

Hyperplastic endometrial glands with atypia may be admixed with those displaying no atypia. The minimum threshold for the diagnosis of focal atypia has not been established; however, focal atypia should be readily found without the need for an intense search (i.e., clearly atypical nuclei seen in most of the cells of several glands) in order to be considered a significant finding. Surface endometrial epithelium should be avoided for the assessment of atypia. In addition, grading the atypia (e.g., mild, moderate, severe) should be avoided because of the lack of reproducibility.5

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

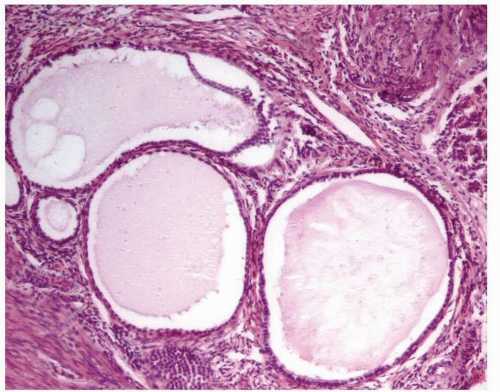

Endometrial Atrophy with Cystic Change

In the atrophic endometrium with cystic changes, there is an apparent shift of the glandto-stroma ratio that could be misinterpreted as endometrial hyperplasia. However, the endometrial epithelium in atrophy is either low columnar, cuboidal, or flattened with rare or no mitotic figures (Fig. 3-8). This epithelium contrasts with the columnar, stratified, mitotically active epithelium seen in hyperplastic endometrium.

FIGURE 3-8: Cystic atrophy. The glands are dilated, but the epithelium is low columnar, cuboidal, or flattened. |

Endometritis

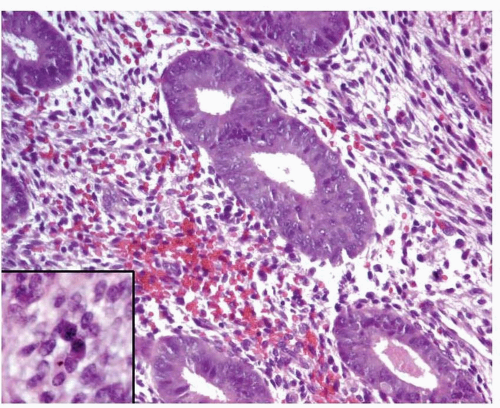

In endometritis, especially in cases with severe inflammation, the glands may be irregularly distributed, thus mimicking endometrial hyperplasia. In addition, nuclear enlargement, a reactive change in these cases (Fig. 3-9), should not be misinterpreted as atypia. The recognition of plasma cells (Fig. 3-9, inset) and usually the presence of a reactive-looking stroma with spindle cells will allow the correct diagnosis.

Endometrial Polyp

An endometrial polyp can display irregularly shaped and crowded glands, thus representing a hyperplastic polyp or a polyp with areas of hyperplasia. This does not pose a problem when the classical histologic features of an endometrial polyp can be recognized in the tissue sampled (i.e., polypoid shape, thick-walled vessels, fibrous or dense stroma). However, when these features are not identified (often due to the small size of the tissue obtained), hysteroscopy and curettage may be required to ensure a correct diagnosis.2

Disordered Proliferative Endometrium

Disordered proliferative endometrium is usually an estrogen-related condition associated with anovulatory cycles. It is characterized by a proliferation of endometrial glands of variable size and shape, without a shift of the normal gland-to-stroma ratio (i.e., from 2:1 to 3:1; in other words, the endometrial stroma does not represent less than one-half to one-third of the cross-sectional area of the proliferation). The glands are lined by proliferative epithelium, with some of the glands becoming enlarged or cystic. Some of the glands can have an irregular contour (Fig. 3-10).3

Endometrioid Adenocarcinoma, International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics Grade 1 (Well-Differentiated Endometrioid Adenocarcinoma)

The diagnosis of endometrial, endometrioid adenocarcinoma, International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) grade 1, is made on one of the following criteria: (1) a confluent glandular growth occupying an area of at least 2 × 2 mm, (2) an extensive papillary pattern, or (3) an irregular infiltration of glands associated with a desmoplastic response.6

Secretory Endometrium

Secretory endometrium can have an abnormal appearance due to artifactual crowding, fragmentation, or poor orientation of the tissue sample. A proper orientation (i.e., evaluating the glands in relation to the surface epithelium) and the recognition of an organized, regular glandular pattern, mimicking a “stack of coins,” in contrast to a disorganized glandular pattern, will allow the distinction of secretory endometrium with artifactual distortion from complex hyperplasia with extensive secretory changes.