Endometrial cancer is the leading cause of gynecologic cancer in the United States, with approximately 40,000 cases diagnosed per year. Endometrial cancer follows only lung, breast, and colon cancers as a cause of cancer in women. It is the most common of the gynecologic cancers.

1 Seventy-five percent of patients with endometrial cancer are postmenopausal, but 3% to 5% are younger than 40 years old.

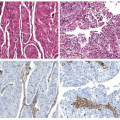

2 Management of endometrial cancer, whether surgical or medical, must take into consideration the histology of the cancer, the stage of the disease at presentation, and the patient’s comorbidities; in young women with early-stage endometrioid carcinoma, the patient’s desire for future fertility is also considered. Ninety percent of endometrial cancers arise in the endometrial glands as opposed to the endometrial stroma or myometrium.

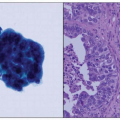

3 There are two types of endometrial cancers that are subdivided by histology. Type I accounts for 80% of endometrial cancer, is caused by hyperestrogenism, usually in the setting of obesity, and arises in a background of atypical hyperplasia. A European study reported that obesity is the cause of up to 39% of all endometrial cancers.

4 Large amounts of adipose tissue aromatize estrogen, leading to increased estrogen effects on the uterus. Endometrial proliferation caused by estrogen may cause neoplastic change in the absence of progesterone, either endogenous or exogenous.

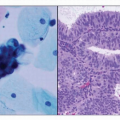

4 Type II endometrial cancer develops in a population without a history of long-term unopposed estrogen, usually in nonobese women. Type II cancer occurs in the setting of an atrophic endometrium.

4 Type I is usually low-grade endometrioid histology, whereas type II includes more aggressive clear cell and papillary serous cancers. Type I is almost always confined to the uterus, and outcomes of survival are considerably better than type II cancer, which has often metastasized prior to diagnosis even without evidence of extensive myometrial invasion.

3Endometrial cancer patients are typically obese and postmenopausal and are at high risk for cardiovascular disease and diabetes. Because the majority of patients diagnosed with endometrial cancer are older and have multiple associated comorbidities, surgical planning must consider issues of cardiac and pulmonary tolerance for major surgery, wound healing, and subsequent ability to tolerate adjuvant therapy, if needed.