General Overview and Incidence

Precursor lymphoid neoplasms or acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) is the second most common leukemia affecting adults with about 1.6 per 100,000 and 6500 cases per year in the United States. In 2018, an estimated 5960 new cases were diagnosed, with 1470 deaths caused by ALL. , ALL occurs in both children and adults with the highest rates between the ages of 3 and 7 years; 75% to 80% of cases occur before the age of 6 years with a secondary rise after the ages of 40 to 50 occurring in 20% of adults. Although pediatric cases are covered in Chapter 4 , this chapter highlights adult cases.

Eighty-five percent of adult cases are of B-cell lineage and have equal incidences in both males and females. The remaining 15% of T-cell lineage cases have a male predominance.

The highest leukemia incidence rates for both sexes were estimated in Australia and New Zealand (Age Standardized Rate [ASR] per 100,000: 11.3 in males and 7.2 in females), North America (10.5 in males and 7.2 in females), and western Europe (9.6 in males and 6.0 in females); the lowest incidence rates were in western Africa (1.4 in males and 1.2 in females). Rates were generally higher in males than females with an overall male-to-female ratio of 1:4. In children, ALL was the main subtype in all studied countries in both sexes and was characterized by a bimodal age-specific pattern. Rates of ALL remained relatively high among adults in selected South American, Caribbean, Asian, and African populations ( Fig. 9.1 ).

Etiology

ALL is a neoplastic malignant proliferation and clonal expansion of hematopoietic cells affecting white blood cells—specifically, the lymphoid cell lineage, which normally fights infection and protects the body against disease—and is a clinically heterogeneous disease. Immature lymphoid cells or lymphoblasts proliferate and build up in the bone marrow, liver, spleen, lymph nodes, and rarely mediastinum, and circulate into the peripheral blood. In the pediatric population, genetic syndromes, including Down syndrome, Fanconi anemia, Bloom syndrome, ataxia telangiectasia, and Nijmegen breakage syndrome, predispose to a minority of cases of ALL. The etiology of ALL is unknown with investigations focused on genetic variability in drug metabolism, DNA repair, and cell-cycle checkpoints that may interact with the environmental, dietary, maternal, and other external factors to affect leukemogenesis. Other factors include exposure to ionizing radiation, pesticides, certain solvents, or viruses such as Epstein-Barr virus and human immunodeficiency virus.

Clinical Presentation

- •

Variable, acute, or insidious symptoms depending on disease extent

- •

Asymptomatic (rare)

- •

Fever

- •

Fatigue

- •

Bone pain

- •

Arthralgia

- •

Headache

- •

Vomiting

- •

Mental status change

- •

Lymphadenopathy

- •

Hepatosplenomegaly

- •

Extramedullary head and neck presentation (common)

- •

Central nervous system, testis sanctuary site predilection

- •

Initial skin, bone, or lymph node lymphomatous presentation with subsequent peripheral blood leukemic presentation

Diagnostic Features

Features of ALL include more than 20% of blasts on hematoxylin-eosin–stained peripheral smears, Wright-Giemsa–stained bone marrow aspirate smears, and hematoxylin-eosin–stained core biopsy and clot sections. The workup should include comprehensive flow cytometry (FC) immunophenotyping and review by hematopathologists for World Health Organization (WHO) ALL subtyping and cytogenetic risk. Note that in ALL, myeloid-associated antigens such as CD13 and CD33 may be expressed, and the presence of these myeloid markers does not exclude the diagnosis of ALL. Fig. 9.2 provides a diagnostic algorithm, and the guidelines in Table 9.1 include those from Europe and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network. , Typical features of B-cell ALL are shown in Fig. 9.3 .

| Diagnostic Step | Results/ALL Subsets | Recommendations |

|---|---|---|

| Morphology | ||

|

| Mandatory Recommended Mandatory |

| Immunophenotype | ||

|

| Mandatory Mandatory Mandatory |

| Cytogenetics/genetics | ||

|

| Mandatory |

|

| Recommended for new clinical trials |

| MRD Study | ||

|

| Mandatory |

| Storage of Diagnostic Material | ||

|

| Highly recommended |

| HLA Typing | ||

|

| Recommended |

Precursor lymphoid neoplasms are references in the updated 2017 WHO classification , and differential diagnoses include ambiguous lineage neoplasms. Criteria for classification of mixed-phenotype acute leukemia (MPAL) should be based on the WHO 2008 criteria.

Laboratory Manifestations

- •

Bone marrow failure: thrombocytopenia, anemia, neutropenia

- •

Leukocyte count elevated initially in 50% of patients

- •

More than 50 × 10 9 /L in up to 25% of patients, higher relapse rate, poorer prognosis

- •

Neutropenia almost always present

- •

Total leukocyte count mirrors the extent of lymphoblasts and total leukemic burden

- •

Rare reactive eosinophilia

- •

High leukocyte count associated with pseudodiploidy, hypodiploidy, t(4;11), and t(9;22)

- •

Anemia in 80% of patients, normochromic, normocytic with low reticulocyte count

Histopathologic Features

- •

Small- to medium-sized blasts similar in size to surrounding red blood cells

- •

Bimorphic morphology; small-, medium-, large-sized blasts

- •

Scanty cytoplasm, velvety chromatin, indistinct nucleoli

- •

Cytoplasmic vacuoles; podlike, tadpole projections; hand mirror sign ( Figs. 9.4–9.6 )

Fig. 9.4

(A) Peripheral blood smear showing increased atypical lymphoblast cells, many slightly larger than red blood cells, scant cytoplasm, few with podlike projections (magnification ×400). (B) Peripheral blood smear shows increased atypical lymphoblasts, podlike projections, scanty cytoplasm, indistinct nucleoli, fine velvet-like chromatin, and few nuclear clefts (magnification ×600). (C) Peripheral blood smear showing increased lymphoblasts, some with nuclear indentations, several nucleoli, scanty cytoplasm, slightly larger relative to red blood cells (magnification ×1000). (D) Peripheral blood smear showing increased lymphoblasts with podlike projections, indistinct nucleoli, scant cytoplasm, and fine chromatin (magnification ×1000).

Fig. 9.5

(A) A 61-year-old male with hypercellular marrow showing an increase in blasts. Inset shows a low-power view of bone marrow biopsy. (B) A 61-year old male with 70% marrow cellularity showing 90% to 95% of marrow cellularity by acute leukemia. The aspirate smear is hypercellular, showing 91.5% blasts; the blasts are small and medium to large with mitotic figures, scant cytoplasm, fine chromatin, nucleoli, some notching, and clefting of nuclei with some vacuolation. The inset shows a low-power view of bone marrow aspirate smear.

Fig. 9.6

Acute lymphoblastic leukemia: hand mirror cell variant. (A) Bone marrow smear showing blasts, with scant cytoplasm, cytoplasmic tail projections, hand mirror cell, fine chromatin, and indistinct nucleoli. (B) Scanning electron micrograph showing blast with uropod extension and microspikes. (C) Electron micrography of hand mirror cell. E, erythrocte; G, glycogen; M, mitochondria; MS, microspikes; N, nucleus.

From Stass SA, Perlin E, Jaffe ES, et al. Acute lymphoblastic leukemia–hand mirror cell variant: a detailed cytological and ultrastructural study with an analysis of the immunologic surface markers. Am J Hematol. 1978;4:67–77.

- •

Morphologically indistinguishable from T-cell ALL ( Fig. 9.7 )

Fig. 9.7

(A) T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia/lymphoma (ALL) is morphologically indistinguishable from B-cell ALL. Both types show hypercellular marrow cellularity by monomorphic blue cell proliferation, infiltration 15% incidence compared with 85% for B-cell ALL. The inset shows a low-power view of bone marrow biopsy. (B) T-cell acute ALL is morphologically indistinguishable from B-cell ALL. Both types show hypercellular marrow cellularity by monomorphic blue cell proliferation with infiltration. Both types can show a bimorphic blast cell population; small- to medium- and large-sized blasts; fine chromatin, indistinct nucleoli, podlike projections; hand mirror sign; and scanty cytoplasm. The inset shows a low-power view of bone marrow aspirate spicule. (C) T-cell ALL is morphologically indistinguishable from B-cell ALL. Some cells have nuclear notching, indentation, grooves, and atypical mitotic figures. (D) T-cell ALL is morphologically indistinguishable from B-cell ALL. Both can show eosinophilia.

Differential Diagnoses

- •

High-grade lymphoma/leukemias such as double- or triple-hit diffuse large B-cell lymphoma ( Fig. 9.8 , Boxes 9.1−9.3 )

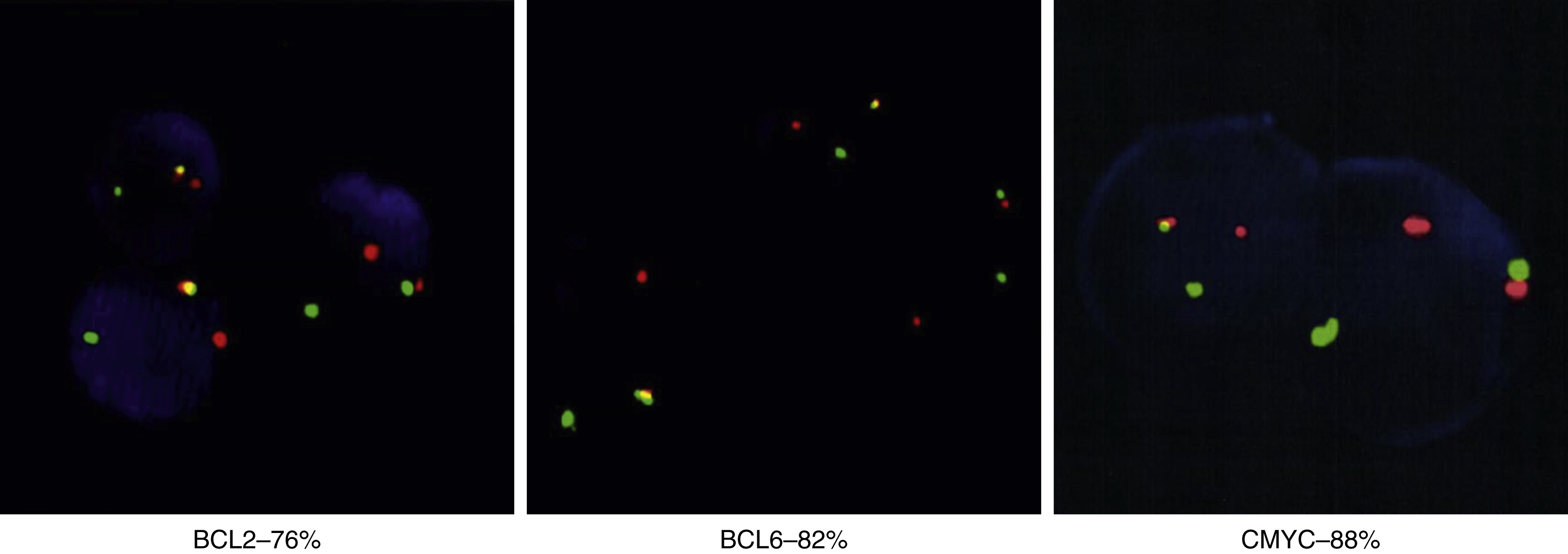

Fig. 9.8

Fluorescence in situ hybridization results differ in high-grade B-cell leukemia/lymphoma versus precursor lymphoid neoplasms. In the BLC2 Dual Color Break apart probe, green indicates the 3’ centromere 18q21 region, red indicates the 5’ telomere 18q21 region, and yellow indicates normal; in the BLC6 Dual Color Break apart probe, green indicates the 3’ centromere 3q27 region, red indicates the 5’ telomere 3q27 region, and yellow indicates normal; and in the CMYC Color Break apart probe, green indicates 3’ telomere 8q24 region, and red indicates 5’ centromere 8q24 region.

Box 9.1

Clinical Features of High-Grade B-Cell Leukemia/Lymphoma Differ From Precursor Lymphoid Neoplasms

From Arber DA, Orazi A, Hasserjian R, et al. The 2016 revision to the World Health Organization classification of myeloid neoplasms and acute leukemia. Blood. 2016;127:2391–2405.

CHOP, cyclophosphamide, hydroxydaunomycin, Oncovin, and prednisone. R-CHOP, rituximab-CHOP.

High-Grade B-Cell Lymphoma

Elderly, 60–70 years of age, male = female incidence

Two or more recurrent cytogenomic events, almost all complex karyotype, MYC likely secondary event, half transformed from indolent lymphoma

More than half, present with widespread disease

Extranodal (30%–88%), bone marrow (59%–94%), central nervous system (45%)

70% to 100% advanced stage, high International Prognostic Index, elevated lactate dehydrogenase

Do not respond to CHOP or R-CHOP; have early relapses after complete remission

Box 9.2

High-Grade B-Cell Leukemia/Lymphoma Phenotype Differs From Precursor Lymphoid Neoplasm Phenotype

From Arber DA, Orazi A, Hasserjian R, et al. The 2016 revision to the World Health Organization classification of myeloid neoplasms and acute leukemia. Blood. 2016;127:2391–2405.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree