PITUITARY NEOPLASMS

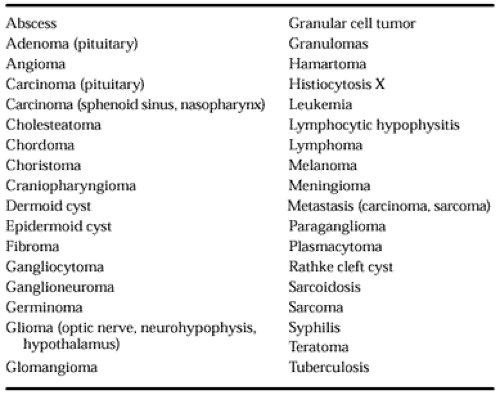

Numerous tumor types occur in the sellar region; they can be epithelial or mesenchymal and benign or malignant4,10 (Table 11-1). Some tumors also occur elsewhere; their histologic appearance is the same in the pituitary as in other organs. Some small tumors cause no clinical or biochemical abnormalities, whereas others destroy large areas of the pituitary, resulting in anterior hypopituitarism, diabetes insipidus, and hyperprolactinemia. Other tumors cause syndromes of hormonal hyperfunction (see Chap. 12, Chap. 13, Chap. 14, Chap. 15 and Chap. 16).

PITUITARY ADENOMAS

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Pituitary adenomas are benign epithelial neoplasms derived from and composed of adenohypophysial cells. They account for ˜10% to 15% of all intracranial neoplasms. Depending on the population surveyed, their reported annual incidence varies

from 1.0 to 7.6 per 100,000 population.1,10 By this measure, pituitary tumors not only are the dominant form of neoplasia arising in the sellar region, but also are among the most frequent primary intracranial tumors encountered in clinical practice. These figures, derived primarily from neurosurgical series, may even underestimate the true incidence of pituitary adenomas, because their frequency in unselected autopsy cases approaches 25%.10 Thus, neoplastic transformation in the pituitary can be considered an exceedingly common event, albeit one that may not always manifest itself clinically.

from 1.0 to 7.6 per 100,000 population.1,10 By this measure, pituitary tumors not only are the dominant form of neoplasia arising in the sellar region, but also are among the most frequent primary intracranial tumors encountered in clinical practice. These figures, derived primarily from neurosurgical series, may even underestimate the true incidence of pituitary adenomas, because their frequency in unselected autopsy cases approaches 25%.10 Thus, neoplastic transformation in the pituitary can be considered an exceedingly common event, albeit one that may not always manifest itself clinically.

Although no age group is exempt from the development of pituitary tumors, there is a clear tendency for these lesions to become more common with age, with the highest incidence occurring between the third and sixth decades of life. Only rarely are they diagnosed in prepubertal patients. Based on surgical series, a female preponderance appears to exist, with women of child-bearing age being at greatest risk for tumor development. The basis of this increased susceptibility in women is uncertain. It may be that the susceptibility is more apparent than real, because manifestations of pituitary dysfunction are generally more conspicuous in premenopausal women, prompting earlier diagnosis by both patients and physicians. Moreover, the incidence of pituitary adenomas in autopsy series is equally distributed between the sexes.10

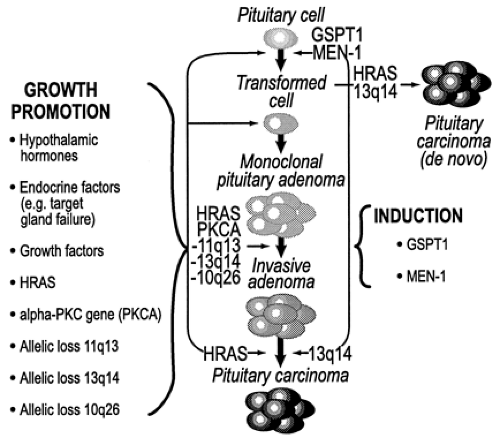

Accumulating evidence indicates the development of pituitary adenomas to be a multistep and multicausal process that, in its most abbreviated form, consists of an irreversible tumor initiation phase followed by a tumor promotion phase (Fig. 11-5). The events necessary to accomplish the process are only superficially understood. Nonetheless, it is known that hereditary predisposition, endocrine and hypothalamic factors, and specific genomic mutations all appear to have some pathophysiologic role in the initiation or progression of pituitary adenomas. Before considering the relative contribution of each of these to pituitary tumor development, it is important to acknowledge that tumor development in the pituitary is a monoclonal process. This observation is of considerable conceptual relevance and provides the background on which other pathophysiologic events must be integrated.

One of the most fundamental and historically contentious issues surrounding pituitary tumorigenesis relates to whether transformation in the pituitary is primarily the product of hypothalamic dysfunction or simply the result of an acquired transforming mutation intrinsic to an isolated adenohypophysial cell. The hypothalamic hypothesis suggests that pituitary adenomas arise as the eventual, downstream, and seemingly passive consequence of excessive trophic influences, emanating from a dysfunctional hypothalamus. Alternatively, the pituitary hypothesis suggests that pituitary adenomas arise as the direct result of an intrinsic pituitary defect, with neoplastic transformation occurring in relative autonomy of hypothalamic trophic influence. Whereas substantial evidence exists in support of both possibilities, the latter concept has been especially favored in view of the lack of peritumoral hyperplasia in association with pituitary adenomas and because many pituitary tumors can be definitively “cured” when completely removed. Neither of these would be expected were hypothalamic overstimulation the dominant tumorigenic mechanism.

Further strengthening the idea that pituitary adenomas result from somatic mutations that occur at the level of a single, susceptible, adenohypophysial cell have been reports concerning their clonal composition. Using the strategy of allelic X-chromosome inactivation analysis, which assesses restriction fragment length polymorphisms and differential methylation patterns in various X-linked genes, several independent laboratories have confirmed a monoclonal composition for virtually all pituitary adenomas.27,28 Validation of the monoclonal nature of pituitary adenomas has been an important conceptual advance because it has established pituitary adenomas as monoclonal expansions of a single, somatically mutated, and transformed adenohypophysial cell. Were hypothalamic overstimulation the dominant initiating event, then a population of anterior pituitary cells should simultaneously be affected and a polyclonal tumor would be the expected result; this has not been the case.

HYPOTHALAMIC FACTORS AND PITUITARY TUMORIGENESIS

Whereas the demonstration that pituitary adenomas are monoclonal derivatives of a single transformed adenohypophysial cell

does conform well to existing paradigms of human tumorigenesis, it should not be interpreted as somehow exonerating hypothalamic influences of a role in pituitary tumor development. On the contrary, the culpability of hypothalamic hormones in pituitary tumorigenesis continues to gain strength, and there has been renewed interest in integrating a role for these hormones in the current multistep monoclonal model.29 The class of hypothalamic hormones at issue are the hypothalamic hypophysiotropic hormones, which primarily include GHRH, somatostatin (SRIF), CRH, TRH, gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH), and dopamine. Produced in hypothalamic nuclei, descending via the portal circulation, and binding to specific membrane receptors on their respective adenohypophysial target cells, these hormones govern the secretory and proliferative activity of each of the principal pituitary cell types. In logical extension of their physiologic trophic activities has been the implication that aberrant activity of these regulatory hormones in the form of excess stimulation or deficient inhibition may contribute to the genesis and/or progression of pituitary adenomas. For example, in states of pathologic GHRH excess, as occurs with rare GHRH-producing tumors (pancreatic endocrine tumors, carcinoids, pheochromocytomas, and hypothalamic hamartomas/gangliocytomas), chronic GHRH stimulation leads to hyperplasia of pituitary somatotropes, GH hypersecretion, and clinical acromegaly. Depending on the duration of exposure to the excess GHRH, progression from somatotrope hyperplasia to adenomatous transformation has been documented in some, but not all instances.24 A parallel phenomenon has been demonstrated in transgenic mice bearing the human GHRH transgene. That these animals develop gigantism, elevated GH levels, somatotrope hyperplasia, and, eventually, GH-producing pituitary adenomas, provides compelling and conclusive evidence of the tumor-promoting properties of GHRH.30 To date, analogous data implicating other hypophysiotropic hormones have been comparatively few; however, the convincing precedence provided by these GHRH data lends, at the very least, some plausibility to the idea that other hypophysiotropic hormones may also share similar tumorigenic potential. Whereas a specific somatic mutation of an adenohypophysial cell is requisite to adenomatous transformation, hypophysiotropic hormones may modify the cell’s susceptibility for such a mutation to occur. Some hypophysiotropic hormones (GHRH, CRH, TRH) are known to induce early-response genes in their respective adenohypophysial target cells, mustering a potent, yet physiologic mitogenic response. Were it to occur, not only would the aberrant overactivity of these regulatory hormones be accompanied by increased proliferative activity of relevant adenohypophysial cells, but the possibility for a transforming mutation also would be correspondingly increased. The extent to which this actually does occur among pituitary adenomas is unknown, although abnormal hypothalamic and other neuroendocrine responses have been demonstrated in patients with pituitary adenomas, including those having undergone “successful” tumor removal.31

does conform well to existing paradigms of human tumorigenesis, it should not be interpreted as somehow exonerating hypothalamic influences of a role in pituitary tumor development. On the contrary, the culpability of hypothalamic hormones in pituitary tumorigenesis continues to gain strength, and there has been renewed interest in integrating a role for these hormones in the current multistep monoclonal model.29 The class of hypothalamic hormones at issue are the hypothalamic hypophysiotropic hormones, which primarily include GHRH, somatostatin (SRIF), CRH, TRH, gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH), and dopamine. Produced in hypothalamic nuclei, descending via the portal circulation, and binding to specific membrane receptors on their respective adenohypophysial target cells, these hormones govern the secretory and proliferative activity of each of the principal pituitary cell types. In logical extension of their physiologic trophic activities has been the implication that aberrant activity of these regulatory hormones in the form of excess stimulation or deficient inhibition may contribute to the genesis and/or progression of pituitary adenomas. For example, in states of pathologic GHRH excess, as occurs with rare GHRH-producing tumors (pancreatic endocrine tumors, carcinoids, pheochromocytomas, and hypothalamic hamartomas/gangliocytomas), chronic GHRH stimulation leads to hyperplasia of pituitary somatotropes, GH hypersecretion, and clinical acromegaly. Depending on the duration of exposure to the excess GHRH, progression from somatotrope hyperplasia to adenomatous transformation has been documented in some, but not all instances.24 A parallel phenomenon has been demonstrated in transgenic mice bearing the human GHRH transgene. That these animals develop gigantism, elevated GH levels, somatotrope hyperplasia, and, eventually, GH-producing pituitary adenomas, provides compelling and conclusive evidence of the tumor-promoting properties of GHRH.30 To date, analogous data implicating other hypophysiotropic hormones have been comparatively few; however, the convincing precedence provided by these GHRH data lends, at the very least, some plausibility to the idea that other hypophysiotropic hormones may also share similar tumorigenic potential. Whereas a specific somatic mutation of an adenohypophysial cell is requisite to adenomatous transformation, hypophysiotropic hormones may modify the cell’s susceptibility for such a mutation to occur. Some hypophysiotropic hormones (GHRH, CRH, TRH) are known to induce early-response genes in their respective adenohypophysial target cells, mustering a potent, yet physiologic mitogenic response. Were it to occur, not only would the aberrant overactivity of these regulatory hormones be accompanied by increased proliferative activity of relevant adenohypophysial cells, but the possibility for a transforming mutation also would be correspondingly increased. The extent to which this actually does occur among pituitary adenomas is unknown, although abnormal hypothalamic and other neuroendocrine responses have been demonstrated in patients with pituitary adenomas, including those having undergone “successful” tumor removal.31

Tumor initiation aside, a more persuasive role for hypothalamic hormones can be envisaged during the tumor progression phase of pituitary tumorigenesis. Given that pituitary adenomas frequently express and retain responsiveness to hypothalamic hormones, the latter have been implicated in facilitating proliferation of the transformed clone. Of particular interest have been a number of reports wherein pituitary tumors themselves were shown to express at the protein and/or mRNA level various hypophysiotropic hormones together with their corresponding receptors. Somatotrope adenomas have been shown to express both GHRH-mRNA transcripts and protein,32,33 experimental corticotrope adenomas have been shown to express CRH-mRNA transcripts,34 thyrotrope adenomas have been shown to express TRH mRNA,35 and gonadotrope adenomas have been shown to express GnRH mRNA and protein.36 These data strongly suggest the possibility that pituitary adenomas may be subject to autocrine and/or paracrine regulation by endogenously produced hypophysiotropic hormones. In the case of GH-secreting pituitary adenomas, tumoral expression of GHRH mRNA was shown to be an adverse event—one associated with higher proliferative activity, invasiveness, increased secretory activity, and a reduced likelihood of postoperative remission.37

In view of the foregoing, it should be clear that despite the monoclonal constitution of pituitary adenomas, a potential role of hypothalamic hormones in their genesis and/or progression is not easily dismissed (see Fig. 11-5).

ENDOCRINE FACTORS

A recurring theme, one borne from both experimental study and clinical observation, relates to the possible predisposing, promoting, or perhaps even the inductive effect of certain altered endocrine states to the development of pituitary adenomas. Of particular relevance are those states of target-gland failure wherein the pituitary is no longer subject to negative feedback effects imposed by target-gland hormones. For example, within the pituitary glands of patients with Addison disease and primary hypothyroidism of long duration, the respective frequencies of corticotrope and thyrotrope “tumorlets” was higher than that observed in control individuals.25,26 Admittedly, only a loose correlation, but stronger still, and of greater clinical concern is the behavior of corticotrope adenomas and thyrotrope adenomas in the setting of bilateral adrenalectomy (Nelson syndrome) and prior thyroidectomy, respectively.38 That such tumors tend to be notoriously more aggressive than those having an intact pituitary-target gland axis emphasizes the potential importance of negative-feedback inhibition in modulating the behavior and progression of these neoplasms.

A final endocrine issue, one having been repeatedly implicated in pituitary adenoma development, particularly PRL-producing adenomas, concerns the role of estrogen as a contributor to transformation and/or neoplastic progression in the pituitary. The tumor-promoting properties of this sex steroid are mediated by specific estrogen receptors which, when ligand activated, dimerize and bind to specific DNA-addressing sites to induce transcription of various target genes governing cell proliferation. Whereas chronic estrogen administration routinely induces prolactinomas in rodents, evidence in favor of a similar relationship in humans has been less convincing. The increasing frequency with which prolactinomas were being diagnosed in the 1970s paralleled the use of oral contraceptives in women, a phenomenon that once invited speculation about a possible causal or predisposing effect of the latter in the development of the former. Several case-controlled studies, however, have failed to substantiate such a relationship.39 Still, estrogens are known to alter the morphology and secretory activity of human adenohypophysial cells, indicating that the anterior pituitary is an important target tissue for estrogen action.40 The observation that the hormonal milieu of pregnancy can, in some instances, stimulate prolactinoma growth indicates a potential responsiveness of these tumors to estrogenic stimulation. That human pituitary adenomas express estrogen receptors has been recognized for some time. In addition, estrogen receptor mRNA transcripts are present in all types of pituitary adenomas and in all cell types of the normal anterior pituitary gland.41 In at least a single but noteworthy instance, one involving a transsexual patient, high-dose estrogen therapy. correlated with the development of a human PRL-producing pituitary adenoma.42 Thus, the link between estrogens and human pituitary tumor formation remains somewhat circumstantial, but sufficiently so, that it cannot be entirely dismissed.

Genomic Alterations: Oncogene Activation.

Accompanying the realization that the somatic mutation of an isolated adenohypophysial cell is an event requisite to pituitary tumorigenesis has been a vigorous attempt to identify and characterize the responsible mutation. Of the genomic and cellular alterations

known to occur in pituitary adenomas, relatively few appear to involve activating mutations of known oncogenes. To date, activating mutations of only two oncogenes have been reported in pituitary adenomas: gsp and H-ras. Whereas the former is encountered with some regularity in somatotrope adenomas and periodically in other pituitary adenoma types, the latter has been identified in only isolated instances.

known to occur in pituitary adenomas, relatively few appear to involve activating mutations of known oncogenes. To date, activating mutations of only two oncogenes have been reported in pituitary adenomas: gsp and H-ras. Whereas the former is encountered with some regularity in somatotrope adenomas and periodically in other pituitary adenoma types, the latter has been identified in only isolated instances.

The only consistent evidence favoring oncogene activation as a transforming mechanism in the pituitary stems from the discovery and characterization of the gsp oncogene, an oncogene first identified in GH-producing pituitary adenomas.43,44 The signal transduction cascades governing the secretory and proliferative functions of pituitary somatotropes converge on the adenylate cyclase second messenger system. In the normal state, the hypothalamic hypophysiotropic hormone (GHRH) is the principal positive regulator of somatotrope function. After binding to its membrane receptor on the somatotrope cell surface, the GHRH-proliferative signal is coupled to a stimulatory, heterotrimeric G-protein, termed Gs, which binds GTP and activates adenylate cyclase. This results in elevations of cAMP levels that, through a series of poorly characterized downstream events, ultimately lead to GH secretion and somatotrope proliferation. Adenylate cyclase activation is normally a self-limiting, transient, and tightly regulated event. This is because one structural component of Gs, known as theα chain, maintains intrinsic GTPase activity that, after transducing the signal, hydrolyzes GTP and returns Gs to its inactive state, thus terminating the trophic signal. Activating mutations of gsp are the result of point mutations in the α chain gene of Gs. The mutant alpha chain has deficient GTPase activity and is therefore incapable of hydrolyzing GTP and “turning off” the proliferative signal. Therefore, such mutant forms of the α chain stabilize Gs in its active configuration, thus mimicking the trophic effects of persistent GHRH action. Bypassing the tight regulatory control normally provided by GHRH, somatotropes bearing the mutant α chain of Gs constitutively activate adenylate cyclase, providing an autonomous and unrestrained capacity for cell proliferation and GH secretion.

Whereas in North American and European studies, activating mutations of gsp have been reported in ˜40% of somatotrope adenomas,44 in Japan, such mutations are rare events.45 In neither geographic setting, however, does their presence confer any significantly distinctive clinical, behavioral, biochemical, or radiologic characteristics to the tumor. In one report, tumors exhibiting gsp mutations occurred in older patients, were smaller, and had lower basal GH levels than wild-type tumors, although this has not been uniformly observed.31,44

Activating mutations of the Gs α chain have also been identified in 10% of clinically nonfunctioning pituitary adenomas and very recently, in 5% of corticotrope adenomas.46,47 and 48 That such mutations should occur in tumors not somatotropic in nature suggests that stimulatory G proteins may underlie intracellular signaling in other cell types as well. As in the case of somatotrope adenomas, nonfunctioning and corticotrope adenomas bearing mutations of gsp do not appear to differ clinically from those tumors lacking this mutation.

Aside from gsp mutations that have been identified with some regularity, the search for additional activating mutations involving other candidate oncogenes has not proved particularly informative. The only relevant finding concerns the very occasional demonstration of mutations involving the H-ras oncogene among isolated pituitary tumors. The first dedicated study of ras mutations in the pituitary involved the screening of 19 pituitary adenomas wherein an activating mutation of ras was identified in only a single instance.49 The noteworthy feature of this case, a prolactinoma, pertained to the unusual aggressiveness of the tumor; the tumor was remarkable for a rather early age of onset, multiple recurrences, very high prolactin levels, resistance to dopamine agonist therapy, and unrelenting invasiveness that ultimately proved fatal. In a subsequent genomic screening of 44 pituitary adenomas, none were found to have mutations of ras.50 In a third study, one focusing on pituitary carcinomas, mutations of H-ras were demonstrated in three of five distant metastases but in none of the primary pituitary lesions, nor in any invasive pituitary adenoma.51 Of these, two were corticotrope carcinomas and the third was a lactotrope carcinoma. Collectively, these data suggest that mutations of ras, while uncommon events in pituitary tumorigenesis, do appear to be associated with an unusually aggressive phenotype and are likely late events in pituitary tumor progression. Furthermore, the presence of H-ras mutations in secondary deposits but not in the primary lesion of pituitary carcinomas is especially intriguing for it suggests that this mutation may play a role in initiating and/or sustaining distant pituitary metastases (see Fig. 11-5).

GENOMIC ALTERATIONS: TUMOR-SUPPRESSOR GENE INACTIVATION

MEN1 Tumor-Suppressor Gene.

Genetic predisposition to pituitary tumor development is restricted to a single and uncommon condition, the MEN1 syndrome. This autosomal-dominant condition is characterized by the simultaneous development of tumors involving the parathyroid glands, pancreatic islet cells, and the pituitary. A variably penetrant condition, only 25% of patients develop pituitary tumors, the majority of which are macroadenomas associated primarily with GH and/or PRL hypersecretion.1,10 Approximately 3% of all pituitary adenomas occur in the context of MEN1. The nature of the genetic defect in MEN1 has recently been identified and involves allelic loss of a putative tumor-suppressor gene at the 11q13 locus.52,53 In its recessive behavior, the MEN1 gene is typical of a tumor-suppressor gene, with susceptible individuals inheriting a germline mutation of one of the two 11q13 alleles. Subsequent spontaneous mutation, inactivation, or deletion of the remaining normal 11q13 locus in susceptible endocrine tissues ultimately leads to tumor formation in the involved tissue.

Once believed to be a genetic defect that accounted for pituitary adenomas occurring exclusively in the context of MEN1, several studies have also demonstrated loss of the 11q13 locus in seemingly sporadic pituitary adenomas. In the earliest of these, allelic deletions of 11q13 were found in two of three sporadic prolactinomas.52 Subsequently, 4 of 12 sporadic GH cell adenomas were found to have deletions involving the 11q13 locus.54 More recently, allelic deletions of chromosome 11 were found in 18% of pituitary adenomas of all major types.55 Collectively, these data suggest that the 11q13 locus is the site of an important tumor-suppressor gene, the inactivation of which may be of pathogenic relevance to the development of both sporadic and MEN1–related pituitary adenomas.

p53 Tumor-Suppressor Gene.

Mutations of the p53 gene represent the single most common nonrandom genomic alteration encountered in human cancer.56 The contribution of p53 gene mutations to pituitary tumorigenesis remains unsettled. Much of the difficulty in implicating or excluding a role for p53 mutations in these tumors has centered on the apparent incongruity between data obtained by conventional genomic screening from that provided by p53 immunohistochemistry studies.57 On the one hand, in all of three studies wherein the p53 gene was screened at the usual mutational “hot spots,” not a single pituitary tumor was identified as having a p53 mutation.50,58 Alternatively, in several reports wherein pituitary. tumors were studied immunohistochemically, conclusive nuclear accumulation of p53 protein was demonstrated in some pituitary tumors.57,59 In one report, nuclear accumulation of p53 was selectively present in none, 15%, and 100% of noninvasive adenomas, invasive adenomas, and pituitary carcinomas, respectively. Moreover, the growth fractions of p53 immunopositive tumors were significantly higher than those immunonegative for p53.59 In reconciling the genomic screening and immunohis-tochemical data, it is important to acknowledge the different

inferences permissible by each methodology. Whereas p53 immunohistochemistry analysis was once regarded as a surrogate means of detecting underlying gene mutations, the concordance between these two methods has not proved as strong as previously believed, and the former cannot be regarded as unequivocal proof of the latter. Therefore, the weight of existing evidence argues against p53 gene mutations as events that contribute to pituitary tumor development and/or their progression. Still, the inability to invoke an underlying gene mutation as the basis for the observed accumulation of p53 protein among aggressive pituitary tumors should not diminish the practical utility of this protein as an immunohistochemical marker of aggressive behavior in this tumor system. Moreover, alternative and equally relevant pathophysiologic mechanisms other than p53 gene mutations may account for p53 immuno-positivity. Precedence in support of this has been provided by other human tumors, such as sarcomas and cervical carcinomas, wherein immunohistochemically apparent p53 accumulation reflects complex formation, sequestration, and resultant inactivation of wild-type p53 by other proteins, producing a state functionally equivalent to that occurring with a gene mutation; similar mechanisms may be operative in pituitary tumors.56

inferences permissible by each methodology. Whereas p53 immunohistochemistry analysis was once regarded as a surrogate means of detecting underlying gene mutations, the concordance between these two methods has not proved as strong as previously believed, and the former cannot be regarded as unequivocal proof of the latter. Therefore, the weight of existing evidence argues against p53 gene mutations as events that contribute to pituitary tumor development and/or their progression. Still, the inability to invoke an underlying gene mutation as the basis for the observed accumulation of p53 protein among aggressive pituitary tumors should not diminish the practical utility of this protein as an immunohistochemical marker of aggressive behavior in this tumor system. Moreover, alternative and equally relevant pathophysiologic mechanisms other than p53 gene mutations may account for p53 immuno-positivity. Precedence in support of this has been provided by other human tumors, such as sarcomas and cervical carcinomas, wherein immunohistochemically apparent p53 accumulation reflects complex formation, sequestration, and resultant inactivation of wild-type p53 by other proteins, producing a state functionally equivalent to that occurring with a gene mutation; similar mechanisms may be operative in pituitary tumors.56

13q14.

The first of the tumor-suppressor genes to be identified, the retinoblastoma gene (Rb) remains the prototypical example of this class of genes. Beyond its role in the development of familial retinoblastoma and various other malignancies and its overall contribution to cell-cycle regulatory control, studies of the Rb gene added a new dimension to the very concept of human cancer, illuminating recessive aspects of the process and the oncogenic consequences that accompany loss of protective genomic elements. The implication that the Rb gene might be involved in pituitary tumorigenesis had a somewhat serendipitous beginning. Transgenic mice in which one of the two germline Rb alleles had been deactivated failed to develop retinoblastomas as anticipated; instead they developed large, high-grade, invasive pituitary tumors.60 On further analysis, these tumors were shown to have lost the remaining normal Rb allele, convincingly implicating a second Rb “hit” as the basis for pituitary tumor development in this model. All of these tumors were found to be corticotropic in nature, immunoreactive for ACTH, and of pars intermedia origin (unpublished observations).

Prompted by the provocative nature of these findings, a number of recent studies have sought to determine the relevance of Rb mutations in human pituitary tumors. In the first report, none of 18 informative pituitary tumors exhibited allelic Rb loss.61 This was further confirmed in a study of 30 informative pituitary adenomas wherein none was found to exhibit loss of heterozygosity (LOH) at the Rb gene locus.62 In another study, however, LOH was found at the Rb locus in all of seven pituitary carcinomas, including their metastatic deposits, and in all of six highly invasive pituitary adenomas.63 The significance of these latter observations vis-à-vis Rb gene mutations, however, was undermined by the finding of Rb protein in tumors exhibiting LOH at the Rb locus. In reconciling the apparent discordance between Rb gene and protein status, together with the two previous studies that excluded Rb mutations within pituitary tumors, the conclusion was made that another putative tumor-suppressor gene, one present on 13q14 but distinct from Rb, must be involved in pituitary tumor progression (see Fig. 11-5).63

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree