Peripheral T-cell Lymphomas

INTRODUCTION

The peripheral T-cell lymphomas are a heterogeneous group of lymphoid malignancies each with a distinct clinical presentation and prognosis. The term “peripheral” denotes mature T-cell neoplasms, differentiating them from the precursor lymphoid diseases T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia and lymphoblastic lymphoma. Treatment regimens for peripheral T-cell lymphomas are generally derived from data extrapolated from trials of aggressive non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) before the advent of CD20-directed therapies of which T-cell lymphomas represent approximately 10% of the studied population. While therapies are often overlapping, T-cell lymphomas in general have an inferior prognosis to their B-cell counterparts. Recent advances have been made, however, with development of treatments specifically directed at peripheral T-cell lymphomas.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

In 2012, there were an estimated 70,130 new cases of NHL in the United States with approximately 18,940 deaths (1). T-cell lymphoma is an uncommon subtype of NHL representing just 12% of all cases (2). The T-cell lymphomas have been subdivided by the most recent WHO classification scheme into predominantly leukemic, nodal, and extranodal variants (Table 35-1) (3). The International Peripheral T-cell Lymphoma project determined the relative frequencies and geographic variation of T-cell lymphoma of subtypes with peripheral T-cell lymphoma-not otherwise specified (PTCL-NOS) being the most common, followed by angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma (AITL), anaplastic large-cell lymphoma(ALCL), and adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma (ATLL) (Figure 35-1) (4). Notably, there are significant geographic differences in the incidence of these entities with PTCL-NOS being the most common in North America and Europe, whereas extranodal nasal NK T-cell lymphoma (ENKTL) and ATLL are more common in Asia due to the seroprevalence of the EBV virus and HTLV-1 viruses, respectively (Table 35-2).

Figure 35-1 International T-cell Lymphoma Study: frequency of subtypes. (From Reference 4.)

PERIPHERAL T-CELL LYMPHOMA NOS

DIAGNOSIS

DIAGNOSIS

PTCL-NOS is the most common subtype of T-cell lymphoma in the United States representing approximately 35% of all T-cell lymphomas (4%–5% of all lymphomas). PTCL-NOS presents at a median age of 61 years with a male-to-female ratio of approximately 2:1 (5). Typically patients present with advanced stage disease (69%), elevated LDH (49%), B symptoms (35%), and extranodal disease (56%) (6). The diagnosis is optimally made based on excisional lymph node biopsies with final needle aspirates normally inadequate. PTCL can be a heterogeneous disease by morphology with most biopsies demonstrating medium-sized or large cells with irregular, pleomorphic, hyperchromatic, or vesicular nuclei with prominent nucleoli and many mitotic figures (3). Immunophenotypic features include CD4 expression more common than CD8 expression with frequent antigen loss of CD5 and CD7, antigens normally expressed on T cells. The T-cell receptor beta chain is usually expressed allowing differentiation from gamma/delta T-cell lymphomas and NK cell lymphomas. Similar to other lymphomas, PTCL-NOS is staged according to the Ann Arbor staging system (Table 35-3) (37). Initial evaluation should include:

• Physical examination with attention paid to nodal areas, hepatosplenomegaly, and performance status.

• Laboratory studies including complete blood count with differential, LDH, uric acid, calcium, and liver function tests.

• Bone marrow biopsy in select cases (of prognostic importance)

• Imaging studies including CT scans of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis. The majority of PTCL-NOS will also be PET avid, and so PET/CT may be obtained.

• Evaluation of cardiac function including ejection fraction for those patients receiving an anthracycline.

PROGNOSIS

PROGNOSIS

The 5-year overall survival for PTCL-NOS is approximately 32%. The prognostic index for PTCL-NOS (PIT) was developed to risk stratify patients based on four adverse risk factors including age greater than 60, performance status of 2 or higher, elevated LDH, and bone marrow involvement. Patients in group 1 with no adverse factors, group 2 with one factor, group 3 with two factors, and group 4 with three or four factors have a 5-year overall survival of 62%, 52.9%, 33%, and 18% respectively (Figure 35-2) (7).

Figure 35-2 Overall survival according to the prognostic index for PTCL-NOS (PIT). (From Reference 7.)

TREATMENT

TREATMENT

Peripheral T-cell lymphomas are traditionally treated like other aggressive NHLs with combination chemotherapy including CHOP-like regimens (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone). The complete remission rate for patients receiving an anthracycline-containing regimen such as CHOP is approximately 56% compared to 70%–90% for patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma receiving R-CHOP (6). The German high-grade NHL study group retrospectively analyzed 343 patients (70 with PTCL-NOS) comparing 6–8 cycles of CHOP to CHOP plus etoposide as well as 14- versus 21-day treatment intervals. While no difference was seen in CHOP 14 versus CHOP 21, there was a statistically significant improvement in 3-year event-free survival favoring inclusion of etoposide (75.4%) compared to CHOP alone (51.0%) (8).

Given the poor outcomes with standard chemotherapy, consolidation with high-dose chemotherapy and autologous stem-cell transplant (ASCT) has been explored. Retrospective studies have shown an improvement in 5-year overall survival to 68% compared to the predicted 32% (9); however, such analyses are confounded by selection bias of the most favorable patients and inclusion of patients with ALK+ ALCL who have a decidedly more favorable prognosis compared to PTCL-NOS. A prospective trial of up-front ASCT excluding patients with ALK+ ALCL showed a 3-year overall survival of 48% (10). The 3-year overall survival rate was 71% for the two-thirds of patients with chemosensitive disease enrolled on the trial that underwent ASCT versus 11% for the patient who did not undergo ASCT. There are also retrospective data for allogeneic stem-cell transplant for patients with refractory peripheral T-cell lymphomas including PTCL-NOS with 2-year overall survival to 55% but with nonrelapse mortality of 22% (11).

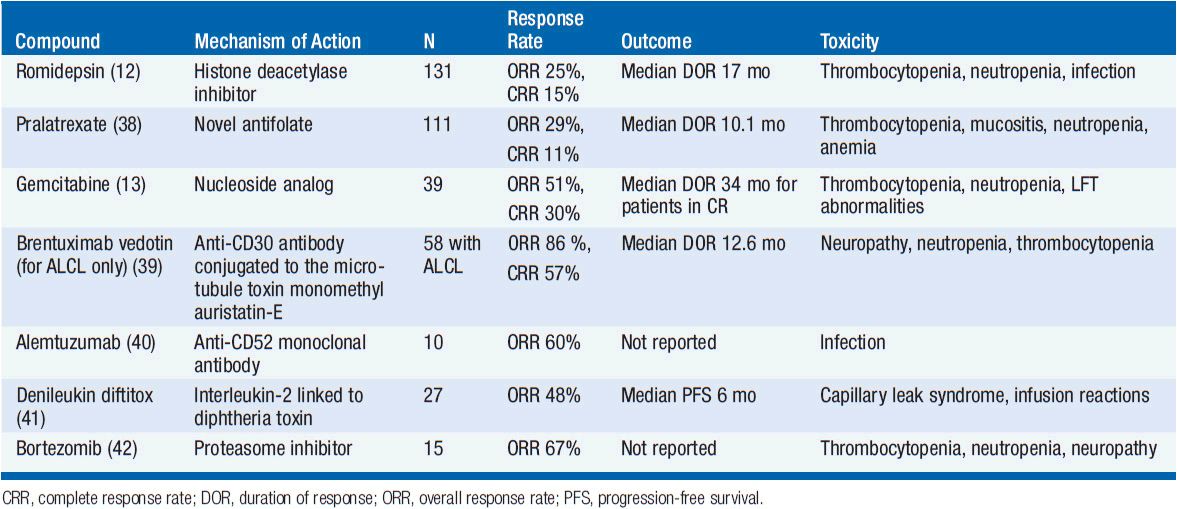

Several novel agents have activity in PTCL-NOS (Table 35-4). The histone deactylase inhibitor romidepsin is approved in the United States for patients with PTCL-NOS having received one prior therapy based on a phase II trial showing a response rate of 25% but with a complete response rate of 15% and a median duration of response of 17 months (12). The main toxicities of romidepsin include cytopenias, GI toxicity, and the potential for arrhythmias. Pralatrexate, a novel antifolate agent, is also approved for patients with relapsed or refractory PTCL-NOS with an overall response rate of 29% and complete response rate of 11% with main toxicities including cytopenias and mucositis (38). Gemcitabine, a nucleoside analog, also has significant activity with overall response rates of approximately 50% (13). There are several other agents that have shown promise in small clinical trials including brentuximab vedotin (for patients with CD30+ disease) (39), alemtuzumab (40), denileukin diftitox (41), and bortezomib (42). Both alemtuzumab and denileukin diftitox have been combined with CHOP-like chemotherapy but early trials were limited due to increased infectious complications. Given the poor predictive outcomes for both up-front and salvage therapy, participation in clinical trials both at diagnosis and relapse are encouraged.

ANAPLASTIC LARGE CELL LYMPHOMA

DIAGNOSIS

DIAGNOSIS

Anaplastic large-cell lymphoma (ALCL) represents approximately 12% of the peripheral T-cell lymphomas seen in the United States each year or approximately 2% of all non-Hodgkin lymphomas (4). ALCL can be further subclassified as expressing or lacking expression of the protein anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK). ALK-positive tumors have a translocation of chromosome 2 and chromosome 5 with resultant fusion of ALK on chromosome 2 with the nucleophosmin gene on chromosome 5 to produce t(2;5), and tend to present in the first three decades of life with a median age of 34 years. ALK-negative patients present at a median age of 58 (14). Both ALK+ and ALK– ALCL often present at advanced stage (58%–65%) with elevated LDH (37%–46%), extranodal disease ~20%, and B symptoms (60%). As with PTCL-NOS, the diagnosis is made on excisional lymph node biopsies showing effacement of lymph node architecture with large anaplastic cells often with reniform nuclei and are positive for CD30, CD25, and epithelial membrane antigen (EMA). The staging and pretreatment evaluations are similar to those as listed above for PTCL-NOS.

PROGNOSIS

ALCL has an improved prognosis compared to PTCL-NOS, but with a distinct difference between the ALK+ and ALK– variants. ALK+ ALCL has a 5-year overall survival of 70% compared to 49% for ALK– ALCL (Figure 35-3) (14). The IPI score typically used for DLBCL is able to effectively risk stratify patients with ALCL regardless of the ALK status.

Figure 35-3 Overall survival according to ALK status in ALCL. (From Reference 14.)

TREATMENT

TREATMENT

Patients with ALCL are treated with anthracycline-containing CHOP-like regimens similar to PTCL-NOS based on extrapolation of data from trials aggressive NHLs including both B- and T-cell lymphomas. As above with PTCL-NOS, retrospective studies evaluating the addition of etoposide to a CHOP-like regimen have shown improvement in both the 3-year event-free survival and overall survival for ALK+ ALCL (75.8% and 89.8%) and ALK– ALCL (45.7% and 62.1%) (8).

Given the excellent prognosis of ALK+ ALCL patients treated with CHOP-like chemotherapy, upfront consolidation with high-dose chemotherapy and autologous stem-cell transplant is not recommended. Patients with ALK– ALCL are much more likely to relapse and go onto salvage therapies including autologous stem-cell transplant resulting in long-term remissions of only 30%–40%. ALCL is uniformly CD30 positive making the CD-30 directed antibody-drug conjugate brentuximab vedotin an appealing agent. A phase II trial of 58 patients (26% of whom had received prior autologous SCT and 62% of whom were refractory to front-line treatment) demonstrated an overall response rate of 86%, complete response rate of 57% with 97% of patients having observed reductions in tumor size (Figure 35-4) (15). The median duration of response was 12.6 months with an estimated 12-month overall survival rate of 70%. Given brentuximab vedotin’s remarkable single agent activity in relapsed and refractory disease, studies are ongoing with this agent in combination with chemotherapy and earlier in the treatment paradigm. The ALK inhibitor crizotinib (recently approved for non-small cell lung cancer harboring ALK mutations) has been tested in four refractory ALK+ ALCL patients all of whom responded (16); however, its role in this otherwise favorable disease subset is unclear at this time as the majority of patients with ALK+ ALCL will be cured with existing standard therapies.

Figure 35-4 Maximum tumor reduction in patients with relapsed refractory ALCL after brentuximab vedotin. (From Reference 15.)

ANGIOIMMUNOBLASTIC T-CELL LYMPHOMA

DIAGNOSIS

DIAGNOSIS

Angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma (AITL) represents approximately 19% of all the T-cell lymphoma seen in the United States every year or approximately 1%–2% of all NHLs (4). A majority of patients with AITL present with the relatively abrupt onset of systemic symptoms including fevers, a pruritic skin rash, nonbulky adenopathy, and organomegaly; a unique clinical presentation compared to other non-Hodgkin lymphomas. The median age of onset is 65 years with a slight male predominance (17). The majority of patients present with advanced stage and extranodal disease is present in approximately one-third of patients. As the historical name of angioimmunoblastic lymphadenopathy with dysproteinemia (AILD) suggests, 30% of patients will present with polyclonal hypergammaglobulinemia, or other protein abnormalities including small amounts of paraprotein or positive tests for autoantibodies. Given the constellation of rapid onset fevers, rashes, and nonbulky adenopathy, patients with AITL are often sent for rheumatologic or infectious disease evaluation before their lymphoma diagnosis, leading to a delay in therapy. Positive tests for rheumatoid factor, antinuclear antibody, Lyme, and other conditions contribute to initially incorrect diagnoses. These patients are frequently started on glucocorticoids confounding the diagnosis of lymphoma with a median time to diagnosis over 6 months from the onset of symptoms. Patients may also present with recurrent infections related to immune deficiency secondary to both the neoplastic process and their immunosuppressive treatments. Ten to twenty percent of patients will have concurrent autoimmune cytopenias, immune-mediated thrombocytopenia (ITP), and/or autoimmune hemolytic anemia (AIHA). As with PTCL-NOS and ALCL, the diagnosis is made on excisional lymph node biopsies demonstrating effacement of lymph node architecture with a paracortical polymorphous infiltrate of small- to medium-sized CD4-positive T cells and proliferation of arborizing high endothelial venules. There is also often an associated expansion of EBV-positive B immunoblasts that are polyclonal. The staging and pretreatment evaluations are similar to those as listed above for PTCL-NOS with the addition of testing for circulating paraproteins and autoimmune cytopenias.

PROGNOSIS

PROGNOSIS

AITL has a poor prognosis with a 5-year overall survival of 32% and 5-year failure-free survival of 18% (4). The prognostic index score is less valuable in this histology since the majority of patients present with high-risk scores.

TREATMENT

TREATMENT

As with PTCL-NOS and ALCL, AITL is customarily treated with CHOP-like regimens based on extrapolation from aggressive NHL trials with a complete remission rate for those receiving an anthracycline-containing regimen of approximately 60%. No survival differences have been observed in patients treated with combination chemotherapy that included an anthracycline compared to those receiving an anthracycline-sparing regimen, but definitive conclusions cannot be reached based on this retrospective data (17). Given the poor outcome in the majority of patients treated with standard chemotherapy, autologous stem-cell transplant in first and second remission has been retrospectively evaluated. In 146 patients with a median follow-up of 31 months, there was an estimated 4-year overall survival of 59%, which is improved compared to historical controls (18). As with all retrospective studies, these findings must be interpreted with attention to biases including selecting for patients that are younger with fewer comorbidities making them eligible for transplant and therefore likely to do better than historical controls regardless of the transplant procedure.

EXTRANODAL NK/T-CELL LYMPHOMA, NASAL TYPE

DIAGNOSIS

DIAGNOSIS

Extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma, nasal type (ENKTL) is an uncommon T-cell lymphoma in North America and Europe representing around 5% of cases but with a significantly increased incidence in Asia where it represents approximately 22% of new T-cell lymphomas and 9% of all lymphomas (4). Patients present at a median age of 43 years with a slight male predominance and symptoms of nasal obstruction due to the presence of a mass lesion in the upper aerodigestive tract. The majority of patients present with localized disease (76%), with a good performance status, normal LDH (63%), and lack of B symptoms (35%) (19). Diagnostic biopsies show frequent ulceration of the mucosal surfaces by a diffuse lymphomatous infiltrate positive for CD2, CD3, and CD56, and will often demonstrate an angiocentric and angiodestructive growth pattern.

PROGNOSIS

PROGNOSIS

ENKTL nasal type has an improved outcome compared to other PTCLs, owing to the more likely presentation at limited stage disease. The estimated 5-year overall survival is about 49%, but is improved in patients with localized disease who have a 5-year overall survival of approximately 76%. Specific prognostic models for ENKTL have been proposed with adverse risk factors including the presence of B symptoms, advanced stage, elevated LDH, and lymph node involvement demonstrating 5-year overall survival of 81%, 64%, 34%, and 7%, for those with 0, 1, 2, and 3 or more risk factors, respectively. (Figure 35-5) (19). Local invasion through bone or soft tissues also negatively affects prognosis.

Figure 35-5 Overall survival for patients with extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma. (From Reference 19.)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree