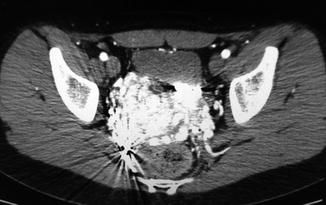

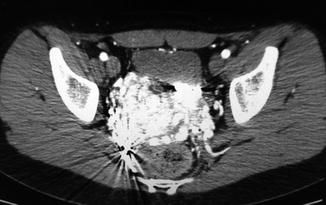

Fig. 47.1

3D CT demonstrating a congenital fusiform Congenital fusiform right iliac aneurysm, involving common and hypogastric artery. Asymptomatic patient

Venous truncular defects are more common. Aplasia of the inferior vena cava is reported in 0.1–1 % of the general population and in up to 5 % in patients under 30 years [8]. Spontaneous DVT is not uncommon [9, 10]. A clinical picture of superficial abdominal dilated veins, as collateral cava–cava circulation, and duplex ultrasound investigation can suggest the diagnosis [11] which is confirmed by angio-CT or angio-MRI [12]. Aplasia of the common and/or external iliac vein is known [13]. Usually collateral circulation through suprapubic veins develops; in case of common iliac vein aplasia also, hypogastric vein-based collaterals compensate the defect which is mainly well tolerated. Aplasia of both external iliac veins is extremely rare [14].

Invasive treatment of inferior vena cava aplasia is not indicated, as collateral circulation often allows an almost symptom-free life. Some patients may develop thrombosis of collaterals, due to thrombophilia, and worsening of symptoms. DVT should be treated by anticoagulation; some authors suggest to precede anticoagulation by fibrinolysis [15]; we observed a case with DVT of collaterals in cava aplasia in which fibrinolysis was very painful for the patient without clinical advantages. In conditions that increase the risk of DVT, like trauma, pregnancy, or surgery, heparin-based prophylaxis is recommended. In deteriorating symptoms due to repeated DVT, ante- and retrograde thrombectomy of the iliac veins and IVC replacement by a ring-supported PTFE graft and temporary mono- or bilateral arteriovenous fistula in the femoral region were performed with 83 % long-term patency [16]. Iliac vein aplasia is also well compensated and does not require treatment.

Venous Extratruncular Malformations

The common site of venous malformations in the pelvis is the perineum, especially the labia majora in females [17, 18] (Fig. 47.2). Involvement of the vagina and also the cervix is possible [19]. Penis VM, sited mainly on the gland, is less common [20, 21].

Fig 47.2

Venous malformation of labia majora

Inside the pelvis, VM may develop venous masses involving the organs, like the rectum, bladder, uterus, prostate, and seminal vesicles (Fig. 47.3). Involvement of the hemorrhoidal veins may cause thrombosis and liver embolization [22]. A rare site of venous malformation is the iliopsoas muscle (Fig. 47.4).

Fig. 47.3

Pelvic MR demonstrating a diffuse venous malformation (bright irregular) surrounding the rectum (arrow). Vagina and bladder are visible above

Fig. 47.4

Venous malformation infiltrating right iliopsoas muscle (bright immage, arrow)

Pure venous malformations of the uterus are rare [22]. A blue rubber-bleb nevus form in the uterus has been described [23]. Sometimes, VM may involve extensively the colon with single or diffuse mucosal VM that may cause repeated bleeding. Intestinal malformations limited to the gut wall are described in Chap. 43.

Ovarian or testicular venous malformations may be related to an insufficiency of nutcracker syndrome.

Female labia majora VM manifests with swelling and pain. Pelvic venous malformation may manifest with pain, due to episodic thrombosis inside the malformation or by rectal or ureteral bleeding.

Female genital VM is easily recognizable by a swelling, generally monolateral, which is compressible and fills out slowly. Duplex scan demonstrates a low-flow malformation. Pelvic VM is best diagnosed by MRI: typically VM are hyperintense in T2-weighted images and contain phleboliths [24]. The nutcracker syndrome is diagnosed by angio-CT or angio-MRI. Hemodynamic evaluation is done by Doppler ultrasound or by direct venous pressure measurement through a catheter introduced from the femoral vein. The higher the grade of the stenosis, the slower the blood flow velocity. In each case direct cannulation of the vein is mandatory in order to define the hemodynamic burden of the stenosis measuring the transvenous pressure gap. The pressure difference between the inferior cava and renal vein is in the range between 0 and 1 mmHg. Values between 1 and 3 mmHg indicate the presence of a compensated or chronic venous hypertension which may exist secondary to the development of collateral vessels. Values above 3 mmHg are typical of the presence of a high-grade stenosis [25].

The treatment of genital VM is mainly based on alcohol or foam sclerosis [22]. The alcohol sclerotherapy is preferred by us in labia majora malformation for the excellent result obtained, while foam sclerosis has a higher incidence of recurrence. In rare cases with less response to alcohol, surgical resection is required. In penis malformations, foam sclerosis is preferred [26].

Symptomatic VM of the pelvis sited around the rectum and extended deeply can be treated by transrectal puncture and alcohol injection after a transrectal echographic study [27] (Fig. 47.5). However, as the complete occlusion of the dysplastic vessels is not possible, symptom recurrence may happen; new treatment should be planned.

Fig. 47.5

Transrectal alcohol treatment of pelvic-infiltrating venous malformation in the case of Fig. 47.3. Patient was free of symptoms (pain and bleeding) after three sessions

In severe bleedings from the rectum nonresponding to sclerosis, surgical procedures are necessary which are difficult and with a high blood loss [28, 29].

VM localized in the site of the iliopsoas muscle can be treated by percutaneous alcohol injections with an inguinal, echo-guided approach. The treatment should be performed in several steps avoiding excessive ethanol injection in a single session because of the posttreatment edema of the muscle that may create painful irritation of the femoral nerve.

Arteriovenous Malformations

Arteriovenous malformations (AVM) are mainly located in a position between the bladder and rectum with a tendency of a lateral prevalence that means a prevailing extension to one side. The feeding arteries are principally the branches of the hypogastric arteries with a prevalence of the vessels sited on the prevailing location. Other feeding vessels, which are commonly associated with the hypogastric branches, are collaterals of the contralateral hypogastric arteries and collaterals of the abdominal aorta, medial sacral artery, and superior rectal artery (Figs. 47.6, 47.7, and 47.8).

Fig. 47.6

Left-sided pelvic AVM in a male

Fig. 47.7

After glue embolization of the AVM through the left feeding vessels, collateral feeders from right appeared

Fig. 47.8

After embolization of right feeders of AVM, the patient is free of fistulas

In males, the malformation may involve the posterior bladder wall, prostate, and seminal vesicles. Sometimes, the malformation may compress the ureters with hydronephrosis. Rarely, AVM may involve the rectal area [30]. In female, several papers refer to AVM located in the uterus [31] (Fig. 47.9). It has been reported that retained products of conception may simulate an endometrial AVM which regresses spontaneously after abortion completion [32].

Fig. 47.9

Uterus AVM (bright area). Rectum is visible below and bladder above

The diagnosis of pelvic cavity AVM is not easy because of the deep location. Rectal exploration may reveal a pulsation in some areas near the rectum. By careful auscultation a slight vascular souffle may be recognized. Transrectal ultrasonography may show multiple anechoic areas with high flow. In females, high-flow areas in the myometrium may reveal the malformation. Angio-CT with 3D images may demonstrate clearly the malformation; angio-MRI is also effective for diagnosis.

Surgery was the only treatment available in the past. However, due to the peculiar anatomy of the area, surgical access revealed difficult and radical removal of the fistulous area and may be complex due to some important structures that may be involved, like the ureter, bladder, seminal vesicles, prostate, and nerves. A team approach together with a urologist is recommended. Careful interruption of the afferent vessels and radical removal of the dysplastic mass was reported in a case [33] and was successful also in one case in our experience.

Catheter embolization is mainly the best approach to pelvic AVM. As this area is fed by several vessels with high possibility of collateral circulation, it is crucial to avoid the occlusion of main branches by spirals or other materials but to focus on nidus closure with glue or alcohol. Treatment may require several steps, as after one apparently successful embolizing session, collaterals often develop (see Figs. 47.6, 47.7, and 47.8) [34].

Uterine AVM can be also treated successfully by the same technique. Fertility may not be compromised; 11 cases of pregnancy after successful embolization of uterine AVM have been reported [35].

A combination of catheter embolization and contemporary occlusion of the draining vein has been reported with excellent results: 83.3 % healed and 16.7 % on partial remission [36, 37].

The combination of embolization and surgery has also been performed, but today it is less frequently done [38].

A complex problem may represent patients who have been treated before by surgical or endovascular occlusion of the hypogastric artery, as the main arterial approach to the nidus is no longer available. Careful angiographic study of collaterals (contralateral hypogastric artery, medial sacral artery, hemorrhoidal arteries, and even deep femoral artery should be explored) often demonstrates other available feeding vessels to the fistula. Retrograde venous access is also an alternative approach to nidus embolization [33].

In the rare case of missing endovascular approach and severe symptoms, surgical treatment is the only possibility. Suture by trespassing stitches into the fistulous area with the aid of an intraoperative Doppler to localize fistulas and immediate control of the effect of the procedure may be the best solution. The collaboration with a urologist is mandatory to avoid damage to the ureters, seminal vesicles, bladder, and nerves. The placement of a catheter in the ureters before operation is recommended. Uterus AVM, if not treatable by embolization, which is rare, can be resolved by hysterectomy.

Lymphatic Malformations

Lymphatic malformations of the vulva are the most common lymphatic dysplasias of this area [39, 40]. Lymphatic cysts of the scrotum are by far rarer [41]. Lymphatic cysts inside the pelvis may be sited in different locations, as the bladder [42]. Macrocystic or microcystic varieties or a combination of both is possible.

MRI exam demonstrates shape, extension, and variety, microcystic or macrocystic.

Macrocystic LM can be treated by direct puncture, aspiration of fluid, and injection of sclerosant substance, like alcohol, OK-432, polidocanol foam, or others [43]. In our experience, we prefer ethanol as it reveals very effective, cheap, and with rare secondary effects because of the lack of outflow vessels in lymphatic cysts, unless venous or AV malformations. Surgical resection has also been performed with good results.

Microcystic LM can be treated by laser with good results.

Gluteal Vascular Malformations

The gluteal area is a prevalent muscular district that contains vessels and nerves. VM in this area may be located intramuscularly or subcutaneously and symptoms depend from the effect of the abnormal vascular mass. Endovascular and percutaneous access are not difficult.

Venous Malformations

VM localized in the buttocks are always of the extratruncular type and may be limited to the subcutaneous level or may infiltrate gluteal muscles; extended forms may involve both areas. Usually only one side is involved: bilateral gluteal venous malformations are extremely rare. Clinically, a nevus and/or multiple bluish small masses may be visible with variable enlargement of the involved buttock (Fig. 47.10).