Pediatric Cancer Policy and Case Advocacy on Insurance, Education, and Employment

Susan L. Weiner

Gilbert P. Smith

This chapter on policy and advocacy for pediatric oncology professionals presents an analysis and update of some of the most important policy and advocacy actions that nonscientist advocates, partnering with health care professionals, can take to improve the treatment, care, and well-being of children with cancer. Part I delineates opportunities for those interested in engaging in childhood cancer advocacy. It describes key childhood cancer policy priorities and their status (as of this writing) to advance the pediatric oncology enterprise, including federal research funding, development of new therapeutic agents, issues in children’s research participation, coverage and reimbursement for treatment and follow-up care. Part II offers resources and strategies to assist health care professionals with case advocacy for individual families, patients, and survivors to ensure better access to health care coverage, quality medical care, and support services.

Advocacy is vigorous, political and goal-directed interaction: in the public sphere with Congress, regulatory agencies, medical and policy institutions (Part I); and with insurers and health care and service providers to resolve reimbursement, care, and quality-of-life problems (Part II). Many families affected by cancer find volunteering in childhood cancer groups meaningful. Families report that volunteering is a way of “giving back” as their children survive; for others, it is a way of actively remembering a lost child. Family advocates’ close collaboration with researchers and clinicians has brought new sophistication to the struggles against pediatric cancer and its aftermath.

PART I: NATIONAL CHILDHOOD CANCER ADVOCACY AND POLICY PRIORITIES

Childhood cancer advocacy is rooted in individuals’ experience and includes a spectrum of opportunities to revise existing and generate new programs and policies to improve care and treatment. While it is convenient to conceptualize national childhood cancer advocacy around the stages of a case from diagnosis through survivorship or end of life, many factors other than advocates’ judgment can determine whether issues are ripe for action; for example, when the national press covers an individual family’s heartrending dilemma or when the political interests of a member of Congress coincide with a childhood cancer issue. Federal legislation with broad national implications can become high priority, if it has consequences for how children are cared for, such as with Medicare and regulations from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). Attention to debates in disease communities outside childhood cancer is important for advocates to be informed abouthealth care debates that translate, protect, and broaden the understanding of children’s needs. Advocates’ challenge is how to be both proactive and reactive with limited resources to monitor and select among the array of possibilities that are time sensitive and most likely to have the biggest payoff for children with cancer. Despite the rapid pace of events, thoughtful research and analysis in collaboration with and informed by researchers, health care advisers, and policymakers should guide the quality of advocates’ priorities and public statements, their alliances and positions taken on federal and state legislation and regulations.

Several large coalitions are the settings in which informed discussions on policy and national events related to childhood cancer take place, including the Alliance for Childhood Cancer (“the Alliance”) and Coalition Against Childhood Cancer (CAC2).1,2 The Cancer Leadership Council (CLC) has about 30 patient,, professional and research organizations representing all types of cancer and is an important opportunity for childhood cancer advocates to keep children’s interests as part of national discussions.3 The Children’s Cause for Cancer Advocacy, the only nonprofit group solely dedicated to national policy and advocacy, is the only pediatric member of the CLC.4

The Alliance, established in 2001 with in kind support from the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO), now has 29 group members, close to a third of which are professional medical societies or research organizations. CAC2, originally an online community of families, grew into a 501 (c) (3) of 62 family-sourced nonprofit organizations and individuals after support and technical assistance r from Alex’s Lemonade Stand Foundation. In addition, there are dozens of small nonprofit, family-founded organizations, some of which are online communities with far-reaching communication impact, such as People Against Childhood Cancer (PAC2) with over 6,100 individual members.5

The Children’s Cause local and national educational workshops for families and survivors are an effort to expand the number of informed and influential national advocates on childhood cancer policy. The Alliance and CAC2 offer lobbying training to prepare families to visit Capitol Hill as part of their separate annual Washington, DC, Action Days events. Families visit members’ offices to to tell their stories and to lobby for timely childhood cancer legislation. Some families, especially those who have lost children, however, are motivated to try to turn a national spotlight on their personal concerns, resulting in issues being influenced by the politics of the moment. One example is the Congressional authorization of the Gabriella Miller Kids First Research Act.6 This law was passed because the story of the death of a child with cancer became associated with politicians’ efforts to terminate taxpayer financing of political party conventions. Funds for the law were appropriated at the end of 2014 for pediatric research through a common fund at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) for one year, and will not necessarily be spent for childhood cancer research.

Advocates share priorities with champions in Congress and work closely with the bipartisan House Childhood Cancer Caucus, which was founded in 2007 and had 104 members as of June 2014. The Caucus is intended to be a Congressional focal point “to raise awareness about pediatric cancer, advocate in support of measures to prevent the pain, suffering, and long-term effects of childhood cancers, and work toward the goal of eliminating cancer as a threat to all children.”7 The Caucus holds annual September summit briefings to highlight, for example, NCI research advances, survivorship needs, and the challenges of drug development. Currently, the offices of Congressmen and Co-Chairs Michael McCaul (R) and Chris Van Hollen (D) act as liaisons for

new policy ideas and draft and promote legislation emerging from the parent/survivor communities.

new policy ideas and draft and promote legislation emerging from the parent/survivor communities.

The policy and advocacy issues discussed in this chapter were selected because they represent enduring concerns of researchers and families and because their timeliness and importance have engaged advocates’ and researchers’ attention and action.

Funding for Childhood Cancer Research

A perennial issue for all concerned with childhood cancer is the amount of federal appropriations for cancer research. Reductions in the past 5 years in Congressional appropriations for biomedical research, and, consequently for the National Cancer Institute (NCI), have alarmed researchers and families alike, threatening the clinical research establishment.8

To help reconcile a diminished research budget while sustaining the national clinical research enterprise, NCI announced in 2014 it would implement recommendations of an Institute of Medicine (IOM) report. Accordingly, NCI reduced the number of adult cooperative groups, to increase their efficiency and increased the per-patient reimbursement rate. These steps would in effect reduced the numbers of patients enrolled in clinical trials.9

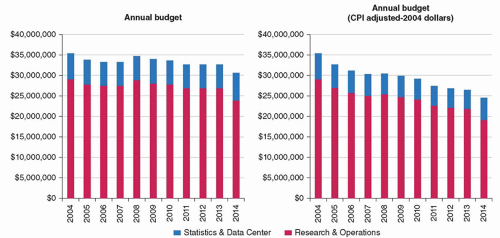

NCI’s decisions held out the possibility of dire consequences for childhood cancer research (Fig. 52.1). Unlike adult cancer research, childhood cancer clinical research depends almost exclusively on federal support (Adamson P. Personal communication, 2014) with the result that NCI continued funding reductions will have dramatic consequences on research for children. The Children’s Oncology Group (COG)’s chair educated the community of advocates in spring 2014 on how the 10-year decline in COG funding affects clinical research. Alliance and CAC2 advocates worked to unify the message for Capitol Hill and the press that funding reductions for childhood cancer research were unacceptable.

Advocates tried to counter reductions further by trying to reauthorize the Carolyn Pryce Walker Conquer Childhood Cancer Act (CPWCCCA). Even though the 2008 law authorized appropriations of up to $30 million for five Fiscal Years (FY), starting in 2009, only $5 million were actually appropriated in the first year and none thereafter. Grants went to increase awareness of treatment protocols, late effects, direct services and a National Childhood Cancer Registry at the Center for Disease Control (CDC). The CPWCCCA was up for reauthorization in the 113th Congress, and the Children’s Cause led advocates in the Alliance and elsewhere to update and reauthorize the law (H.R. 2607 and S. 1251). The new bill expanded a biospecimen repository with associated clinical and demographic information on children, adolescents and young adults with the capability of tracking cancer survivors’ late effects. The reauthorization bill also required a report to Congress from the Governmental Accountability Office (GAO) on how to remove barriers to pediatric oncology drug development (see below).10,11

The bleak federal research funding picture has cast new light on the importance of industry and philanthropic support for biomedical research.12,13 The pharmaceutical industry historically has funded relatively little pediatric oncology research, and private philanthropy has by necessity taken a more active role. St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital (SJCRH) is an exceptional example of what private philanthropy can do for children with cancer.

Some private charitable sources are now in the position of attempting to compensate for NCI’s budget cuts. COG recently formed its own 501(c)(3) organization to receive extramural funding from industry and charities.14 CureSearch, no longer the exclusive fundraising arm of COG, continues to award grants primarily to COG researchers.15 The St. Baldrick’s Foundation is the largest foundation for pediatric oncology research (excluding SJCRH’s charity) with many millions of dollars directly supporting research in COG as well as grants for research infrastructure, professional education, supportive care, and survivorship. In 2013, St. Baldrick’s Foundation partnered with Stand up to Cancer and the American Association of Cancer Research to award $14.5 million for a new translational network to develop new immunotherapy approaches for hard to cure childhood cancers through a marriage of genomics and immunotherapy.16

Other national pediatric cancer fundraising organizations have grown in prominence and impact, including Alex’s Lemonade Stand Foundation, the Children’s Brain Tumor Foundation’s and its funding for new a brain tumor tissue bank consortium, the Pediatric Brain Tumor Foundation and its network of research institutes, Curing Kid’s Cancer, and Cookies for Kid’s Cancer. Large private groups fund research on adults as well as children, such as the Sarcoma Foundation of America, the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society, the Lymphoma Research Foundation and the American Cancer Society. Hundreds of small family-founded

groups raise and award much-needed seed money in the $5,000 to $75,000 range for young researchers and local institutions.

groups raise and award much-needed seed money in the $5,000 to $75,000 range for young researchers and local institutions.

Discovery, Development, and Access to New Therapies

Pediatric oncology therapeutic development remains among the most complex and difficult policy challenge for families and researchers. New therapeutic approaches are critical to improving children’s survival and quality of life, since despite high cure rates for some cancers, others remain incurable, and those cured often suffer late effects from the very chemotherapy and radiation therapy that saved their lives. Advocates and researchers are frustrated by the time required to move new agents from adult development into pediatric cancer trials, delaying children’s ready access to potentially better therapeutic options. As biomedical insights into the underlying mechanisms of cancer burgeon, there remains no economically beneficial way for the biopharmaceutical industry to discover and develop new agents for pediatric malignancies, given the large number of different pediatric cancers with the small market size. Companies continue to be concerned that adverse events in pediatric clinical trials may derail the adult drug development pathway for an agent, despite the apparent lack of supporting evidence. As a result, pediatric cancer researchers often have considerable difficulty gaining access to promising anticancer agents prior to their approval by FDA for an adult indication.

Advocates have recently worked on these challenges by trying to revise the pediatric provisions of the Prescription Drug User Fee Act (PDUFA), a “must pass,” every 5-year reauthorization vehicle intended to improve Food and Drug Administration (FDA)’s efficiency in drug review. PDUFA, passed in 2012 and renamed the Food and Drug Safety and Innovation Act (FDASIA), was an opportunity to include language to protect and improve drug development for children.17 Advocacy, especially by the Children’s Cause for Cancer Advocacy, the American Academy of Pediatrics and Kids v Cancer, was effective in modifying key pediatric provisions. Perhaps most important in incentivizing pediatric access to oncology drugs was the permanent reauthorization of the Best Pharmaceutical for Children Act (BPCA). BPCA awards companies 6 months of marketing exclusivity for an agent approved for adults if pediatric research on that agent is conducted according to an FDA written request. From 1998 to April 2014, FDA granted pediatric exclusivity to 201 compounds, of which 8% (17) were anticancer agents, only one of which had childhood cancer as its first indication.

Also permanently reauthorized was the Pediatric Research Equity Act (PREA). To accelerate pediatric access to new agents, PREA allows FDA to require companies to develop a Pediatric Study Plans (PSP) for all new agents in development for adults. Companies must present these plans no later than 60 days after the date of the FDA end-of-phase 2 meeting. As currently structure, PREA has no impact on pediatric access to cancer agents. Its enforcement depends on an agent having the same indication for children as for adults. Further, waivers of the PSP requirement are allowed for drugs with orphan indications thereby excluding all drugs to treat pediatric cancers. Advocates and researchers worked in 2012 to change the language of PREA so that FDA could require pediatric studies if the molecular target of the drug for an adult oncologic indication is highly relevant to specific pediatric cancer(s). This effort was unsuccessful.

Working closely with rare disease groups, advocates used the opportunity of PDUFA to enact an additional incentive in the form of a voucher program for rare pediatric diseases with the expectation that it might stimulate oncology drug development. Originally termed the “Creating Hope Act,” and driven by Kids v Cancer, the law permits FDA to award a voucher to a company developing a brand new drug or biologic that would treat only a rare pediatric disease. Modeled on a program for neglected tropical diseases, the voucher requires FDA to review a new pediatric rare disease drug or biologic application in 6 rather in than the standard 10 months. A pediatric rare disease voucher can then be sold to another company, which can use it for FDA rapid review of any new agent The pediatric rare disease voucher program is currently a pilot program, and the GAO is expected to evaluate its overall effectiveness after three vouchers have been awarded.

Advocates accomplished another permanent change in 2012 PDUFA that affects pediatric oncology drug development. The Pediatric Subcommittee of the Oncologic Drugs Advisory Committee (PODAC) was permanently reauthorized. PODAC is the only open public meeting on pediatric oncology drug development and is an important platform at which companies can present their plans for pediatric studies for drugs in development for adults. Advocates worked to codify a diverse PODAC membership, including patient advocates, researchers, agency and industry representatives.

Changes in FDA law and regulation such as these intended to promote pediatric access to new agents may seem small and difficult to attain. However, advocates, consulting closely with researchers and regulators, continue to pursue strategies to brighten the prospects for rational access to new agents to treat children. Advocates are currently preparing for the 2017 PDUFA reauthorization as an opportunity to press Congress for changes that can improve pediatric oncology access to new agents. Efforts will be directed again at changing the language of PREA to give FDA new authority to require pediatric oncology studies and to renewing the pediatric rare disease voucher program. Nonprofit venture philanthropy is under discussion in several settings as a potentially important strategy to address the economic barriers of small pediatric patient populations.18,19,20

Single Patient/Compassionate Use and Expanded Access to Investigational Agents

Pressure from advocates has drawn attention to how FDA handles requests for individual patient access to investigational drugs outside of clinical trials. For some families whose children are severely ill and who no longer may be eligible for treatment trials, final hopes can rest on obtaining access to an unapproved agent that they believe will save their child’s life. A recent instance of a family’s difficulty obtaining an unapproved agent went viral online, drawing attention from the national press.21 Nearly 20,000 people signed a petition in March 2014, requesting a pharmaceutical company to give a dying child access to an investigational drug whose effectiveness was not known.

These requests pose a thorny ethical dilemma, since the needs of an individual dying patient can be seen as contrasting with the broader societal need for the agent to be available to more children through more rapid FDA approval. Family advocates are deeply divided about the wisdom of using public pressure and social media to enable an individual child to gain compassionate access. On the one hand, the first premise of being a parent is to try to do everything possible to save a child’s life, and therefore getting access to any potentially life-saving drug is the top priority. On the other hand, supporting drug access for an individual child, when there are other children, perhaps less fortunate or with fewer resources to attract media attention, who cannot access the drug, is inequitable. Perhaps most troubling, very sick children run the serious risk that the administration of an investigational therapy without sufficient data about its effects can increase suffering at the final stage of life.

Several states have recently passed laws that simplify individual patients’ access to investigational agents.22 “Right to try” laws now allow individuals’ to be treated with any unapproved agent with a letter or prescription from a physician. These laws by pass FDA individual access procedures. These laws may also discourage patients from enrolling in clinical trials and disrupt the pace of the routine drug development and approval process. Insurance companies are unlikely to pay for the single use of an investigational

drug, and companies may want to charge patients for the agents. In the end, companies must be willing to supply a drug to an individual patient for them to arrange compassionate access. Right to try laws open the real possibility that unscrupulous companies may peddle their products to desperate patients without FDA oversight. FDA’s regulations for single patient INDs and for expanded access programs provide both access and safeguards for individuals requesting unapproved agents.23

drug, and companies may want to charge patients for the agents. In the end, companies must be willing to supply a drug to an individual patient for them to arrange compassionate access. Right to try laws open the real possibility that unscrupulous companies may peddle their products to desperate patients without FDA oversight. FDA’s regulations for single patient INDs and for expanded access programs provide both access and safeguards for individuals requesting unapproved agents.23

Shortages of Approved Drugs

A critical drug access issue emerged in the national press in 2011, consuming advocates’ attention and resources. Supplies of chemotherapy and other agents essential for treatment declined dramatically. Researchers reported to ASCO and others that short supplies threatened the conduct of standard cancer treatment regimens and delayed new and disrupted ongoing clinical trials. During 2011-12, when a pediatric oncologist (Michael Link, MD) was chair of ASCO, drug shortages became a key lobbying issue for the cancer community at large.

Advocates learned quickly that the causes of drug shortages are complex and difficult to remedy.24 Factors include pharmaceutical industry consolidation, manufacturing delays, shortages of raw materials and contamination. Many cancer drugs in short supply are off-patent made by generic drug companies and are no longer sufficiently revenue producing. Evidence soon emerged that substituting other agents in standard treatment regimens produced poorer outcomes for pediatric Hodgkin lymphoma patients.25 Advocates worked with Congress to include provisions in FDASIA that gave FDA new authority to require companies’ notification to FDA 6 months before shortages occur. Since companies cannot be required by law to manufacture their drugs, tougher sanctions than notifications will be needed to remedy this complex problem.26 Drug shortages continue to be a major problem for which advocates and researchers will seek legislative solutions in support of increased FDA’s authority.27

Advocates’ Direct Engagement in Research

One important way family advocates monitor the pulse of emerging policy issues is to become closely involved in the research enterprise. Family advocates’ perspectives are uniquely different from those of researchers and physicians. Families’views are uncompromised by professional or business interests and have a single focus on how to advance what is best for the treatment and care of children. Families,are vitally interested in realizing the promise of precision medicine for their children, and the recent renewed emphasis on “patient-focused” research is increasing advocates’ opportunities to make their views known in the clinical research process.28 Programs at NCI and FDA screen advocates and include training and orientation before advocates are placed in settings where they bring the patient/family reality to research deliberations.

NCI’s Office of Advocacy Relations (OAR), part of the NCI Director’s Office, is the primary link for pediatric cancer advocates to enhance their understanding of how to “advise” in a strategic forum, help “design” a research program, “review” a research proposal or educational materials and assist to “disseminate” scientific information to nonscientists.29 The Patient Advocate Steering Committee (PASC), outside of OAR, involves advocates further in high-level NCI’s Disease-Specific Steering Committees. Disease specific committees are intended to “ensure that the concept evaluations include consideration for the patient community at large with a special focus on minority and underserved populations.” At present, as NCI revises its clinical trials organization and review process, federal mandates ensure that patient advocates will continue to be participants in the research process.

Both the COG and Pediatric Brain Tumor Consortium (PBTC) have active patient/family committees, who review and comment on concepts, trial designs and schedules of procedures. Advocates’ input, as one example, has resulted in simplification of consent and assent forms and for PBTC concept review, a “patient/family considerations” evaluations category.

FDA’s Office of Health and Constituent Affairs, whose charge is broad extramural liaison, oversees an organized “Patient Network” to assure “that patient perspectives are taken into consideration during drug development and policy issues through the patient representative and patient consultant programs.”30 FDA’s Patient Network website, newsletter and annual training are important educational resources for cancer advocates.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree