PEARLS

❖ The essential setting for evaluating an older person is a noncompeting environment that is well lit, has nonglare surfaces, is wheelchair accessible, and is color contrasted with low-pile carpet or nonslip floors.

❖ The initial interview should focus on functional decrements and include questions on history, social support, and subjective findings.

❖ When physically assessing older adults, consider breaking up the initial evaluation into several visits.

❖ When assessing pain in older adults, use additional pain tools, such as pain diagrams, pain diaries, pain language tools, and general pain evaluations.

❖ The environment should be assessed for safety and optimal functioning as an older person becomes frailer and he or she becomes more dependent on the environment.

❖ Psychosocial aspects of an older person may be awkward for the physical therapist to assess; however, using the straightforward approach will be easiest.

Of all the elements of patient care, evaluation is the most crucial. A comprehensive evaluation provides the practitioner with all the necessary information for designing an appropriate program. Because older patients often present with complex problems because of multiple pathologies and the effects of aging, a thorough evaluation may be more difficult. Nevertheless, it is even more important to determine the exact nature of the problem. This chapter divides evaluation into 8 main components: preparation, expectations, the interview, physical assessment, environmental assessment, psychosocial assessment, functional assessment, and home assessment. Assessment is covered briefly here in terms of the initial evaluation. For a more detailed account, please refer to Chapter 10.

PREPARATION

Setting

What background is essential for a good evaluation of older patients? A quiet noncompeting environment is important because there is a high probability that the patient will have some hearing loss,1 and background noise will make it difficult for the patient to hear questions. In addition, many older persons suffer from vision loss. Therefore, examination areas should be well lit with no glare. Therapists should provide enough room for movement, and doorways and room space should be large enough to be wheelchair accessible. The room should have a comfortable, sturdy, 18-inch (or higher) chair available.1 Optimally, the bed or treatment table should be automatically adjustable for height. The floor should have a low-pile carpet or a low-gloss nonslippery floor. Finally, the colors in the room should be those that make the older person most at ease, such as reds, oranges, gold, and beige. These colors should also be contrasted to avoid visual misinterpretation.2 This scenario is for a clinical setting; however, many evaluations are done in the home. In the home setting, try to imitate this background as closely as possible.

Tools

Any general evaluation form can be sufficient for the initial evaluation visit; however, specific forms for physical (orthopedic, neurologic, and cardiopulmonary), environmental, psychosocial, and functional assessment are helpful and often cue the clinician to ask appropriate questions. It should be noted that many of the functional evaluation forms listed in Chapter 10 can be given to the patient prior to the evaluation. Forms for different diagnoses can be used by the clinician to look for specific problems.

Timing

When is the best time to do an evaluation? There are times during the day when people perform better. It would be impossible to schedule evaluations to fit each patient’s peak performance; however, a thorough clinician should ask the patient when he or she performs the best and note it. Only one time is contraindicated for an initial evaluation—immediately following a large meal.3 This is due to the decrease in blood flow to the brain for 1 hour after a large meal, which is most apparent in older patients.3 Therefore, it is not good to overtax the system by doing an evaluation immediately after a large meal.

EXPECTATIONS

A clinician unfamiliar with treating geriatric patients can expect different levels of performance from an older person in an initial evaluation compared to a younger person. Clinical experience shows that the older patient cannot tolerate a similar history taking session as that of younger patients. The initial evaluation may need some modification, especially in the physical performance area. Robin McKenzie, for example, requests that his patients both extend and flex the trunk approximately 10 times.4 This type of repetition is too rigorous for most older persons. Physically, most older persons can tolerate 1 or 2 repetitions of a movement and can tolerate rolling into different positions 1 to 2 times. For these reasons, a clinician may need to anticipate 2 sessions to complete a thorough evaluation.

INTERVIEW

Although a great deal of information can be collected from the interview process, much of it is not useful. Limiting responses and directing questions are the keys to a successful interview.

A good way to start an interview is to ask the patient “Why are you here to see me?” A good follow-up to this question is “What do you expect from physical therapy?” These 2 questions give the interviewer the main problem (usually in functional terms) and the patient’s goals (again, in functional terms).

The next important piece of information is the relevant history. One way to get this information is to ask, “How did this happen?” Follow-up questions along this line are “Have you had anything similar to this before?” and “What do you think contributed to this?” To obtain additional medical history information that could impact the rehabilitation progress ask, “What other medical problems do you have that I need to know about?” or “What other medical problems do you have that may affect your progress?”

Other important information that can easily be gathered in the initial interview is the patient’s social support system. For example, a question like “Do you live alone?” followed by “Who is the main person that helps you when you are ill or having difficulties with any of your daily activities?” will give the clinician important insight into the patient’s social support. Age, weight, and medication usage can all be asked in the initial interview.

The initial interview session can also be used to gather information on subjective areas. Pain assessments are the major subjective tests used by the geriatric therapist. When assessing pain in the older adult, the clinician should be aware of 2 different presentations of symptoms in the older patient from the younger. First, older people tend to under-report pain, and second, they are less sensitive to pain.5,6 There are several pain ratings available for assessing pain in older adults; some are better than others.

PHYSICAL ASSESSMENT

Physical assessment is probably the most important aspect of the physical therapist’s time with a patient. Physical assessment will provide the therapist with both subjective and objective data from which to develop and monitor a treatment program.

The application of physical assessment tools in the geriatric patient is similar to younger patients, except for the variables listed in the beginning of the chapter and the following:

❖ The therapist should relate physical findings to function. For example, what is the patient unable to do with shoulder flexion limited to 90 degrees?

❖ An entire assessment may need to be broken up and conducted in several sessions. The older person may not have the endurance to complete an entire physical assessment.

❖ Psychosocial components must be considered along with physical parameters (see subsequent section).

❖ Pain can be a major component and should be assessed thoroughly in an older person (see next section).

Pain Assessment

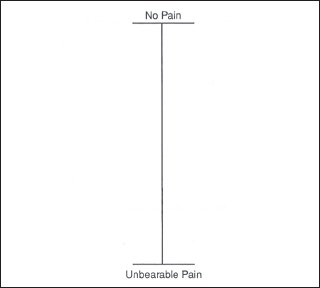

Pain evaluation tools can be divided into 4 categories. The first includes general pain evaluation tools (eg, asking a patient to rate his or her pain as severe, moderate, or mild). Pain diagrams are the second type of pain evaluation tools. An example of a pain diagram is the visual analog scale, which is simply a 100-mm line with a label at the top and bottom.7 Figure 9-1 is an example of a visual analog scale. To use this scale, the older person simply marks the place that corresponds to his or her pain. The clinician then measures the distance from no pain to the mark. For example, on an initial evaluation, a patient may have 67 mm of pain on the visual analog scale, and 2 weeks later she marks her pain as 23 mm. However, pain diagrams pose potential problems for older patients. The tests require abstract thinking, and older persons do not tend to perform as well on tests of this nature.6

Figure 9-1. The visual analog scale.

The third group of pain assessment tools are pain language tools. A good example of a pain language tool is the McGill Pain Questionnaire.8 This 1-page questionnaire uses different pain descriptors to rank the person’s pain. This particular test has been used with older populations; however, specific reliability and validity for this test and the older population have not been demonstrated.

The final type of pain tool is a pain diary, which is a running record of the person’s pain. There are pros and cons for this tool. A pain diary can be useful because it helps the patient focus and become aware of how pain affects his or her life.9 A major drawback of it is that the patient often becomes too focused on his or her pain as a result.10

The interview process can provide a wealth of information for the clinician. According to Echternach and Rothstein,11 the information synthesizing process begins in the interview process, even before the clinician lays hands on the patient.

How To

Once the interview session is over, the physical process begins. If a treatment session could be extended to 4 hours, it would be possible to evaluate every aspect of the person during the physical assessment session. However, in reality, treatment sessions often last less than 1 hour, and it becomes crucial that the clinician chooses to assess the areas that may affect the problem. The other reason for focusing on the major problem area is that the older person may have limited stamina.12

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree