“The pathology of melanoma is discussed in relation to surgical diagnosis and management. Pitfalls that may result in problems of clinicopathologic communication are emphasized. A compelling vision for the future is that all tumors will be characterized by their driving oncogenes, suppressor genes, and other genomic factors. The success of targeted therapy directed against individual oncogenes, despite its limitations, suggests that a repertoire of targeted agents will be developed that can be used against a variety of different tumors, depending on the results of genetic testing. Nevertheless, histopathologic diagnosis and surgical therapy will remain mainstays of management for melanoma.”

Key points

- •

Pathologic evaluation of a clinically selected lesion remains the “gold standard” for diagnosis of melanoma.

- •

Ancillary diagnostic techniques are becoming available that may enhance the specificity of pathologic diagnosis.

- •

Pathologic attributes are important for predicting outcome and planning therapy.

Definition and diagnosis of melanoma

Malignant melanoma may be simply defined as a malignant neoplasm derived from melanocytes. Most melanocytes reside in the skin in the basal layer of the epidermis, separated by keratinocytes. Other sites where melanocytes may exist and melanomas may occur include the uveal tract of the eye and various mucosal surfaces, such as the sinonasal mucosa, oral mucosa, and vulva.

Reproducibility of diagnosis of melanocytic proliferations is good for wholly benign lesions such as compound nevi, and for fully malignant lesions such as American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) stage 2 melanomas. Distinctions among various patterns of atypical nevi, melanoma in situ, and “thin” invasive melanomas are less reliable. There is also considerable variation of terminology from institution to institution. In a recent proposal that might alleviate some problems of uncertainty in classification, it has been suggested that lesions might be placed into treatment categories termed “MPath-Dx,” analogous to a similar scheme used for codification of mammograms. In this system, the usual terms for a particular institution would be employed for diagnosis and an MPath-Dx category, delineating possible considerations for management would be appended, with the goals of facilitating communication among institutions and of enabling studies of outcome in relation to management of homogeneous categories of melanocytic proliferations.

Definition and diagnosis of melanoma

Malignant melanoma may be simply defined as a malignant neoplasm derived from melanocytes. Most melanocytes reside in the skin in the basal layer of the epidermis, separated by keratinocytes. Other sites where melanocytes may exist and melanomas may occur include the uveal tract of the eye and various mucosal surfaces, such as the sinonasal mucosa, oral mucosa, and vulva.

Reproducibility of diagnosis of melanocytic proliferations is good for wholly benign lesions such as compound nevi, and for fully malignant lesions such as American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) stage 2 melanomas. Distinctions among various patterns of atypical nevi, melanoma in situ, and “thin” invasive melanomas are less reliable. There is also considerable variation of terminology from institution to institution. In a recent proposal that might alleviate some problems of uncertainty in classification, it has been suggested that lesions might be placed into treatment categories termed “MPath-Dx,” analogous to a similar scheme used for codification of mammograms. In this system, the usual terms for a particular institution would be employed for diagnosis and an MPath-Dx category, delineating possible considerations for management would be appended, with the goals of facilitating communication among institutions and of enabling studies of outcome in relation to management of homogeneous categories of melanocytic proliferations.

Classification and histopathologic diagnosis of melanoma

Although it has been suggested that melanoma is 1 disease, it is not true that 1 set of criteria can be used to diagnose all cases of melanoma. To the contrary, there is striking variation among different forms of melanoma, which has led to their being categorized in various classification schemes. An important foundation of classification of melanomas is based on patterns of evolution of melanoma, from a patch or plaque in the skin termed the “radial growth phase” (RGP), to a tumorigenic proliferation called the “vertical growth phase” (VGP), with increasing risk of metastasis. In the current World Health Organization classification, melanomas are classified mainly on the basis of their RGP components into superficial spreading, lentigo maligna, and acral subtypes. Tumors that lack an RGP are termed “nodular melanoma.” This category accounts for only about 10% of melanomas but a disproportionate number of deaths, because all of them are in the VGP ( Box 1 ).

Superficial spreading melanoma

Nodular melanoma

Lentigo maligna

Acral–lentiginous melanoma

Desmoplastic melanoma

Melanoma arising from blue nevus

Melanoma arising in a giant congenital nevus

Melanoma of childhood

Nevoid melanoma

Persistent melanoma

Radial growth phase: nontumorigenic melanoma

Most melanomas begin as a patch or plaque in the skin that spreads along the radii of an increasingly irregular circle in the skin, and is therefore known as the RGP, a term derived from clinical morphology but more often applied histologically. Clinically, the lesions tend to acquire attributes that have been captured in a number of algorithms, the best known of which is the “A, B, C, D, E” rule, in which A stands for asymmetry, B for border irregularity, C for color variegation, D for diameter greater than 4 mm, and E variously stands for “evolution” or “elevation.” This clinical morphology is, of course, the gross pathology of the melanoma.

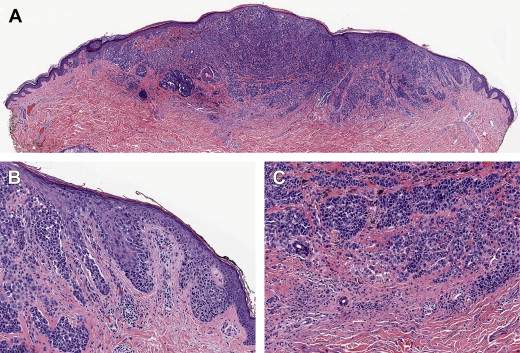

Histologically, there is an increased number of cytologically atypical melanocytes in the epidermis. These lose the normal contact inhibition, which leads to the separation of their cell bodies by keratinocytes. There are 2 important patterns of proliferation. The best known of these is that of nests or clusters of melanocytes, which tend to rise up into the epidermis, partially replacing it in what has been termed a “buckshot scatter” or “pagetoid” pattern, the latter term reflecting a histologic resemblance to Paget’s disease of the breast ( Fig. 1 ). The other main pattern of proliferation is that of continuous basal proliferation, where the atypical melanocytes replace basal keratinocytes. This pattern is termed “lentiginous” because it resembles the pattern of proliferation of melanocytes in lentigines. In lentiginous proliferations, single cells tend to predominate over nests. These patterns have been well illustrated in a recent study that correlated phenotypic features with mutation status of the oncogenes BRAF or NRAS. Melanomas with BRAF mutations showed distinct morphologic features such as increased nest formation and pagetoid scatter, thickening of the involved epidermis, and sharper demarcation to the surrounding skin; they had larger, rounder, and more pigmented tumor cells. These were also associated with a lesser degree of chronic solar damage (CSD), and generally corresponded to the superficial spreading melanoma subtype. The NRAS or other oncogene-related melanomas tended to have a predominantly lentiginous pattern, with few nests, less pigment, smaller cells, and a higher degree of CSD, corresponding to the lentigo maligna subtype.

The patterns of proliferation in the epidermis—nested, pagetoid, or lentiginous—correlate with clinical and epidemiologic evidence that have long been known and have been formulated recently in terms of a “divergent pathways hypothesis.” In this hypothesis, there are 2 major patterns of sun exposure that correlate with melanoma risk. In one of these patterns, “acute–intermittent” sun exposure (eg, weekend/recreational activity) results in melanomas that tend to occur in a younger age group and in skin with mild to moderate CSD. These melanomas histologically tend to exhibit features of the “BRAF/superficial spreading melanoma” subtypes. In the other pattern, “chronic–continuous” sun exposure that can result from occupational exposure tends to be associated with melanomas with features more characteristic of lentigo maligna melanoma, and associated with moderate to severe CSD.

The other major pattern of RGP melanoma is acral melanoma, which occurs in the hairless skin of the palms and soles, and also in the nails, and is called “subungual melanoma.” This form of melanoma is not likely to be caused by solar damage because the thick stratum corneum in acral sites diffuses sunlight and sunburn typically does not occur, even after prolonged exposure. These melanomas bear some resemblance to lentigo maligna melanoma in that the predominant pattern of growth is lentiginous, which has resulted in their being characterized as “acral–lentiginous melanoma.” There are other histologic differences between acral–lentiginous melanoma and lentigo maligna melanoma, including larger cell size and more prominent pigmentation in the majority of cases. These acral–lentiginous melanomas also tend to resemble melanomas occurring in mucosal sites with a histologic pattern that has been termed “mucosal–lentiginous.” Pagetoid melanomas also occur in acral sites and their genomic biology is said to resemble those of the lentiginous acral melanomas, so that the preferred current classification is “acral melanoma.”

In terms of AJCC staging criteria, the vast majority of RGP melanomas are “thin” by Breslow’s criteria, and by Clark’s levels of invasion the majority of them fall into levels I (in situ) and II (invasive into the papillary dermis but failing to fill and expand it and therefore in most cases nontumorigenic and associated with an excellent prognosis). In a study by Gimotty and colleagues of more than 26,000 melanoma cases from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results tumor registry, a subset of almost 50% of the cases had a probability of 10-year survival of 99% based on the properties of ulceration, mitogenicity, Clark’s levels, Breslow thickness of less than 0.78 mm, and age less than 60 years. Most of these cases represent “pure” RGP cases.

Vertical growth phase: tumorigenic melanoma

After a variable period of evolution of the RGP, these lesions are at risk of acquiring the next stage of progression, called VGP, in which the lesional cells may grow up above the level of the skin, or invade down into the skin, forming a tumorigenic or mass lesion developing within the antecedent plaque (see Fig. 1 ) or in some cases apparently de novo. Nodular melanoma is a pattern of melanoma in which a tumorigenic VGP is formed and in which an antecedent RGP component is not evident. There may have been a short lived, in situ component that was overwhelmed by a tumorigenic VGP. Nodular melanomas therefore lack the clinical “ABCDE” criteria and also lack many of the histologic features mentioned, such as pagetoid scatter and lentiginous proliferation.

The VGP results in most of the attributes of melanoma that account for risk of metastasis and death. These include tumor thickness according to Breslow; Clark’s level of invasion, which is a measure of extension into the skin; the mitotic rate; the presence or absence of ulceration, which is almost always associated with the VGP rather than the RGP; and other attributes considered to be of lesser importance such as tumor infiltrating lymphocytes, RGP regression, lymphovascular invasion, and others.

An important VGP variant is desmoplastic melanoma (DM). This condition may be difficult to diagnose both histologically and clinically, and if tumor is left on the margin it will usually recur, often as a more significant lesion. It has been recognized that “pure” DM has a better prognosis than its microstaging attributes might suggest; however, when DM is “mixed” with a component of epithelioid growth, the prognosis is significantly worse. Sentinel node involvement is less likely to occur with “pure” DM; however, opinions about the utility of sentinel node biopsy are mixed. Neurotropism is relatively more common in DM and increases the risk of local recurrence in any melanoma.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree