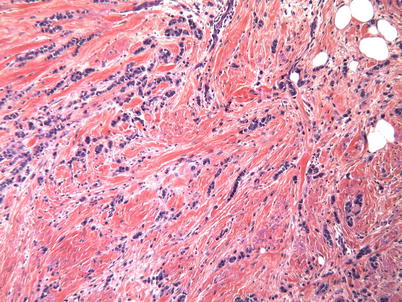

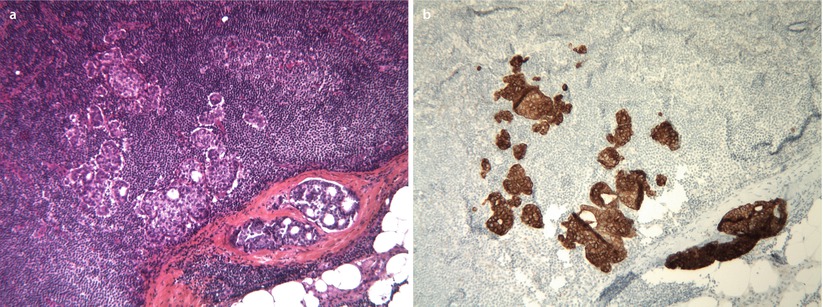

Fig. 15.1

Invasive breast cancer of no special type

Breast cancers, other than invasive carcinomas NST, may belong to one of a number of major categories as follows: special types of invasive breast carcinoma, epithelial-myoepithelial tumours, fibroepithelial tumours, mesenchymal tumours and lymphomas. In this review, these BC subtypes will be described as they are important for understanding both clinical behaviour and in directing treatment. Some of the rarer subtypes will not be addressed here in detail. Several good articles have recently been published which cover these subtypes in more detail for the interested reader [2, 3], and several are also covered in other chapters in this book (► Chaps. 46 and 47).

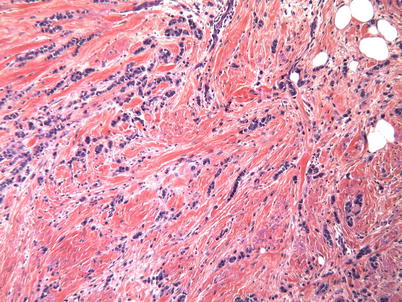

The second most frequent histological subtype of BC, and the most frequent special type of BC, is invasive lobular carcinoma (ILC, 10–12% of all BCs) (◘ Fig. 15.2). It has a particular clinical behaviour pattern which corresponds to its particular genotype: mutation or loss of the gene for E-cadherin, a cellular adhesion molecule (CDH1) [4]. Lobular carcinomas tend to have a more diffuse pattern of spread within the breast making them difficult to clinically and radiologically characterise (tumour size often underestimated both clinically and on imaging). They also may be mammographically occult so magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is often advocated to fully characterize these lesions before offering conservation surgery. They are also more likely to be multifocal [5] which again justifies the use of preoperative MRI [6]. Lobular breast cancers tend to be histological grade 2, to be oestrogen receptor (ER) positive, to be HER-2 negative and to have an unusual pattern of metastatic spread where they are more likely to infiltrate the viscera (stomach, bladder, bowel, etc.) than other breast tumour subtypes [7].

Fig. 15.2

Invasive lobular cancer

Among the BC types other than invasive ductal or lobular carcinoma, some are characterized by a particularly good or poor prognosis. Tubular, colloid (mucinous), adenoid cystic or secretory breast carcinomas, in general, have a good prognosis, so most of them can be effectively controlled by first-line surgery and anti-oestrogens (+/− adjuvant radiotherapy if appropriate), without the need for systemic chemotherapy [2, 3, 8]. For example, tubular carcinomas are usually small, node negative, low grade and ER+ and have an excellent prognosis compared to other invasive carcinomas of NST [9]. In contrast, micropapillary, metaplastic and pleomorphic lobular breast carcinoma has an intrinsically aggressive behaviour pattern and poor prognosis [10–12].

Medullary breast carcinoma is a very rare BC subtype but deserves special attention as it was the first type of BC which demonstrated that a dense lymphocytic infiltration in a high-grade cancer can be associated with a favourable prognosis. It was first described almost 60 years ago [13] and named medullary because of its close resemblance to a lymph node. However, besides its high-grade and dense lymphocytic infiltrate, this BC subtype is also characterized also by syncytial architecture and circumscribed margin. This combination is now considered classically to denote a «true» medullary BC, whereas other BCs rich in tumour-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) belong mostly to two other categories, atypical medullary BC and BC with medullary features. «True» medullary BC is a rare tumour (comprising less than 0.5% of all BCs), has the «triple-negative» phenotype (ER-, PR-, HER2-) and is TP53-mutated. It has been demonstrated, during the past 10 years, that most medullary BCs or BCs with medullary features are triple negative or HER2+. The triple negative ones frequently arise in patients having a germline BRCA1 mutation [14]. If this mutation is not present, other hereditary mutations may be found, mostly in genes involved in DNA damage repair (DDR) [15]. In addition, such tumours may have numerous other anomalies in the DDR pathway and are said to have «BRCAness», i.e. pathobiological features typical of BCs associated with BRCA1 mutation [16]. The presence of BRCAness is usually assessed by several molecular assays and is demonstrated to be associated with increased tumour sensitivity to DNA-damaging agents like platinum salts and/or to the inhibitors of poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) [17–19]. These molecular features influence the therapeutic approach to BC, as tumours with BRCAness can often be successfully treated by neoadjuvant therapies containing DNA-damaging agents, which allows for a reduction tumour burden («downstaging») and subsequent breast conservative surgery. A high number of tumour-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) in a BC, the most striking «medullary feature», have been demonstrated in several recent studies to be a powerful prognostic and predictive biomarker in BC [20]; however, at the time of writing this chapter, no clinical decisions regarding BC can be made on the basis of TIL level – they can only be used for selection of patients for clinical studies of neoadjuvant chemo- or immunotherapies.

Inflammatory breast cancer is characterized by tumour infiltration into the dermal lymphatic vessels causing oedema of the skin overlying the breast. This diagnosis is principally clinical, as the «orange peel» breast skin texture (peau d’orange) is observed clinically and can be documented by a skin biopsy [1]. This subtype of BC has a very unfavourable prognosis and is treated initially by neoadjuvant systemic chemotherapy [21] (see ► Chap. 48, locally advanced breast cancer).

Other rare tumour types include desmoid tumours, phyllodes tumour, primary sarcoma and lymphoma (most of which are dealt with elsewhere in this book (► chaps. 46 and 47).

15.2 Pathology Input and Role in the Diagnosis of Breast Cancer

The daily practice of the breast pathologist has changed substantially over the last 30 years. Mass screening has profoundly modified the natural history of BC, its clinical presentation and, consequently, its management. The BC samples submitted for pathological analysis are smaller (obtained by diagnostic core biopsies or conservative surgery), as indeed is the average tumour size (remarkably decreased due to mass screening and early detection); paradoxically, the number of samples that need to be examined by the pathologist is growing (exhaustive management of preinvasive lesions, microcalcifications, surgical margins). Nowadays, the diagnosis of BC is established before surgery in the vast majority of cases by diagnostic percutaneous biopsy. The global number of frozen section analyses remains stable as the role of this procedure has switched from surgical BC diagnosis to sentinel lymph node (SLN) assessment in some but not all countries/centres. The wider implementation of intraoperative SLN assessment is associated with a new specific workflow in some pathology labs, dedicated to the search for macro- and micrometastases either by classical histopathological techniques or by newer molecular biology methods. Intraoperative assessment of margins is also sometimes undertaken.

The era of targeted therapies has modified the pathological evaluation of BC, which has moved from the purely morphological, on microscopically identified lesions (diagnosis of malignancy, tumour histopathological grade, lymph node (LN) involvement) to the phenotypical, using IHC (tumour proliferation degree, presence of LN micrometastases and of therapeutic targets such as HER2 and hormone receptors (HR)) and evaluation based on molecular biology methods (in situ hybridization (ISH), molecular profiling via gene expression analysis, search for LN micrometastases).

15.3 «What is new»: Evolution of Practices in Pathology (◘ Box 15.1)

15.3.1 Micro- and Macrobiopsies

The pathological diagnostics of BC are usually performed on small specimens in modern practice (i.e. core needle biopsies) in cases of frankly malignant lesions, or on macrobiopsies, in some cases of microcalcifications detected in the breast tissue by radiological examination (e.g. vacuum-assisted biopsies, excision biopsies).

15.3.2 Communication Between Radiologists and Pathologists

The modern breast pathologist works in close communication with other physicians involved in patient care. Discussion of individual clinical cases at the multidisciplinary tumour board meetings, through clinical-pathological and radiological consensus and discussion, is of particular importance and should be the standard of care in all institutions involved in BC diagnostics and/or treatment.

The communication between radiologists and pathologists is indispensable in the initial phase of breast lesion diagnostics: even before the gross (macroscopic) analysis of a breast tissue specimen, the pathologist needs to know the degree of radiological suspicion (ACR classification) and the type of mammographic abnormality. This information determines the type and extent of breast specimen sampling. In particular, if microcalcifications in the breast are radiologically detected, their presence and localization in macrobiopsy samples should be verified and precisely reported by the radiologist. The radiological findings should be compared to the pathological assessment of the sample, and in case of significant discordance, additional biopsies should be considered [22]. The diagnosis of BC on biopsies does have certain limitations (◘ Table 15.1), and the ones provoked by inadequate sample size and/or quality can and must be overcome by adequate communication between the sample providers (usually radiologists) and the pathologists.

Table 15.1

Difficulties of diagnostics on biopsies

Correct identification of pre-invasive lesions implying surgical verification (atypical ductal hyperplasia, lobular neoplasia, etc. …) |

Diagnosis of microinvasion |

Establishment of the grade and of other histoprognostic and predictive parameters on small samples (in case of pre-operative or neoadjuvant treatments) |

15.4 Pathology Report of Invasive Breast Cancer

The first mission of the pathologist is to provide an accurate diagnosis of malignancy [23].

15.4.1 General Information: Identification

Detailed information must be provided to ensure the correct identification of the sample and correct orientation of a surgical specimen. Besides demographic data and clinical history, it is essential to specify the side and the exact location of the lesion(s) within the breast, as well as to provide details of any prior treatment, i.e. neoadjuvant chemo- or hormone therapy, or re-excision for unsatisfactory margins.

15.4.2 Gross Examination (Specimen Orientation, Frozen Section Examination, Surgical Margin Status and SLN Examination)

Electrocautery introduces artefacts into histologic evaluation of breast specimens. The maximal effects are on the surface of the specimen, which, regrettably, also represents the surgical margins. These artefacts can alter morphology to the extent that distinction between benign and malignant lesions is impossible. When the surgical specimen (lumpectomy, partial mastectomy or mastectomy) is removed, specimen orientation must be performed in the operating room by the surgeon or a trained nurse. The type and number of orientation marks have to be discussed and agreed between the breast surgeons and pathologists and ideally should be to a standardized protocol. One such protocol is to use a short suture for superior, long for lateral, medium for medial and others as appropriate. Use of radio-opaque markers such as metal clips may be helpful if specimen X-ray is to be performed but are not adequate alone as they need to be removed by the pathologist before specimen processing which may damage the tissues. The specimen should be sent unsliced to the pathology department.

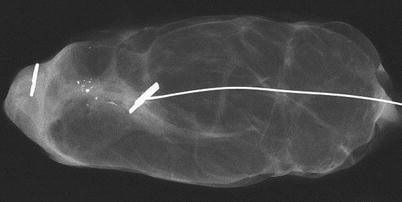

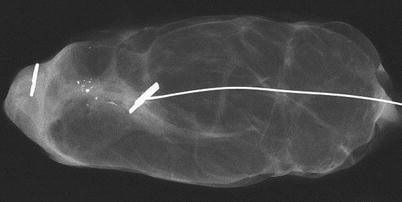

When handling an image-guided excision (that is an impalpable lesion marked using a guide wire, ROLL or a radioactive seed), the first step is to obtain a digital or X-ray image of the specimen, in order to be sure that the intended radiographic abnormalities have been totally excised. The specimen radiography can be performed either in the operating room, the radiology department or the pathology laboratory. The images are essential to the pathologist to guide sampling of specimens with impalpable lesions (◘ Fig. 15.3).

Fig. 15.3

X-ray image of a breast specimen containing a metal clip

The specimens are then inked to mark the surgical margins, eventually with each colour corresponding to a specific orientation (◘ Fig. 15.4).

Fig. 15.4

Inking of a breast surgical specimen

Before fixation, the pathologist will macroscopically examine the specimen and decide whether or not to perform a frozen section on an area of the specimen. This procedure is indicated as an intraoperative assessment when the preoperative diagnosis is uncertain, when an unexpected lesion is seen and in cases where the surgeon is concerned about grossly suspicious surgical margins. There is no indication to perform frozen sections in cases of microcalcifications extending to the surgical margin in the absence of a mass lesion however. In such cases the frozen section procedure could impair the morphology and waste tissues and eventually diminish the capacity of the pathologist to make the right diagnosis, for example, between a proliferative lesion and an in situ carcinoma.

If the surgical procedure involved taking intraoperative margin shaves or in case of re-excision for positive margins (biopsy cavity margins, shaved margins), the new cut surface will also be inked specifically. The specimen should be serially sectioned, perpendicularly to the inked surface to permit analysis of the widest extent of the new surgical margin.

Before fixation, the pathologist will describe the gross anatomy of the surgical specimen and measure the tumour(s) in three dimensions and its distance to the margins. Specimen weight should also be recorded before fixation either in the operating room or in the pathology department. In the final pathological report, this macroscopic description and the results from the frozen sections (if performed) are reported for medicolegal reasons.

Ideally the oriented breast specimens should be sliced prior to fixation to ensure more rapid and thorough fixation (◘ Fig. 15.5). If this is not possible, the sample has to at least be incised centrally to help penetration of the fixative. The fixative should be 10% buffered formalin and the fixation duration between 6 and 72 h [24, 25]. If fixation is significantly delayed, it may permit tissue degradation which may render it impossible to adequately grade the tumour. Ideally therefore fixation should be carried out within 1 hour of surgery.

Fig. 15.5

Slicing of a breast specimen

In case of SLN biopsy, the node is first examined macroscopically by the pathologist. A touch preparation or frozen sections of a slice can be performed intraoperatively if required. Intraoperative diagnosis can also be established by a molecular biology method (such as the one-step nucleic acid technique, OSNA) [26]. However, this practice is not standard in the majority of European Units for a number of reasons including cost, interpretation of whether positive results equate to micro- or macrometastases compared to standard validated node assessment methodology and the increasing trend for more selective ANC in patients with low-volume nodal disease based on MDT review of full histology. For the same reason, frozen section examination is usually performed only in cases of highly suspicious SLN macrometastasis so that the surgeon can decide on further axillary management and whether it is appropriate to complete an axillary clearance or not (see algorithm on ► Chap. 24). The LNs obtained by axillary dissection are processed by complete inclusion of each node after slicing, usually at 2 mm intervals, except for the obviously metastatic ones (which will have only one slice per node).

15.4.3 Description of Microscopic Findings

The pathology report should provide the following: diagnosis of the lesion, surgical margin status (free or involved and specifying whether it is in situ or invasive disease at the margin as well as the distance from the lesion to each specified surgical margin), a report of lymph node involvement (number uninvolved and number involved, subclassified according to macrometastases, micrometastases or isolated tumour cells) and the presence of lymphovascular invasion (emboli). In addition, a detailed description of the cancer biotype (grade, hormone receptor status, HER-2 status) is mandatory. All those data are indispensable for adjuvant therapy decision-making at the MDT and whether further surgery is indicated [1, 22, 23]. The use of a standardized synoptic pathology report with a check list is highly recommended [27, 28].

Surgical Margins

This has been a subject of intense debate in recent years with a general downwards trend towards narrower acceptable margins based on several papers showing that on detailed sectioning of mastectomy specimens, breast cancer often has small satellite lesions such that to achieve 100% clear margins, a 10 cm margin is required [29, 30]. The only margin proven to confer a significant impact on local recurrence after conservation surgery is a positive margin (0 mm, tumour at ink) [31, 32]. The adequacy of a «no tumour at ink» margin was recently endorsed by several national and international bodies [33–35]. However, there are concerns that whilst this may be adequate for invasive disease, there is less certainty for DCIS, and indeed the most recent ASCO guidelines have advocated a 2 mm margin for DCIS. In many MDTs a margin of less than 1 mm will be reviewed to look at disease pattern and other risk factors to decide if this is acceptable and minimal acceptable margins may vary by country and by unit.

Elements of the TNM Stage (◘ Table 15.2)

The TNM staging was revisited in 2002 (version VI); important changes were made in terms of the introduction of LN metastasis classification and in integration of IHC and molecular biology parameters related to the wide implementation of SLN examination. The 2010 version of TNM has only slight variations [36], compared to the 2002 version. Below is a description of the pTNM staging system (p stands for pathologic), which is determined by the microscopic evaluation of the samples (as opposed to clinical TNM).

Table 15.2

Pathologic TNM or pTNM classification for breast cancer staging, 7th edition (2010), as measured on surgical specimens

Pathologic TNM staging of the primary tumour (pT) | |

pTX | Primary tumour cannot be assessed |

pT0 | No evidence of primary tumour |

pTis | Carcinoma in situ |

pTis (DCIS) | Ductal carcinoma in situ |

pTis (LCIS) | Lobular carcinoma in situ |

pTis (Paget) | Paget disease of the nipple not associated with invasive carcinoma and/or carcinoma in situ (DCIS and/or LCIS) in the underlying breast parenchyma. Carcinomas in the breast parenchyma associated with Paget disease are categorized based on the size and characteristics of the parenchymal disease, although the presence of Paget disease should still be noted |

pT1 | Tumour ≤20 mm in greatest dimension |

pT1mi | Tumour ≤1 mm in greatest dimension |

pT1a | Tumour >1 mm but ≤5 mm in greatest dimension |

pT1b | Tumour >5 mm but ≤10 mm in greatest dimension |

pT1c | Tumour >10 mm but ≤20 mm in greatest dimension |

pT2 | Tumour >20 mm but ≤50 mm in greatest dimension |

pT3 | Tumour >50 mm in greatest dimension |

pT4 | Tumour of any size with direct extension to the chest wall and/or to the skin (ulceration or skin nodules) |

pT4a | Extension to the chest wall, not including only pectoralis muscle adherence/invasion |

pT4b | Ulceration and/or ipsilateral satellite nodules and/or oedema of the skin (including the «peau d’orange»/«orange peel» aspect), which do not meet the criteria for inflammatory carcinoma |

pT4c | Both T4a and T4b |

pT4d | Inflammatory carcinoma |

Pathologic staging of regional lymph nodes (pN) a | |

pNX | Regional lymph nodes cannot be assessed (e.g. previously removed, or not removed for pathologic study) |

pN0 | No regional lymph node metastasis identified histologically. Note: Isolated tumour cell clusters (ITCs) are defined as small clusters of cells ≤0.2 mm, or single tumour cells, or a cluster of <200 cells in a single histologic cross-section; ITCs may be detected by routine histology or by IHC methods; nodes containing only ITCs are excluded from the total positive node count for purposes of N classification but should be included in the total number of nodes evaluated |

pN0(i-) | No regional lymph node metastases histologically, negative IHC |

pN0(i+) | Malignant cells in regional lymph node(s) ≤ 0.2 mm (detected by haematoxylin-eosin stain or Iby HC, including ITCs) |

pN0(mol-) | No regional lymph node metastases histologically, negative molecular findings (reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction, RT-PCR) |

pN0(mol+) | Positive molecular findings (RT-PCR) but no regional lymph node metastases detected by histology or IHC |

pN1 | Micrometastases or metastases in 1–3 axillary lymph nodes and/or in internal mammary nodes, with metastases detected by sentinel lymph node biopsy but not clinically detectedb |

pN1mi | Micrometastases (> 0.2 mm and/or > 200 cells, but none > 2.0 mm) |

pN1a | Metastases in 1–3 axillary lymph nodes (at least 1 metastasis >2.0 mm) |

pN1b | Metastases in internal mammary nodes, with micrometastases or macrometastases detected by sentinel lymph node biopsy but not clinically detectedb |

pN1c | Metastases in 1–3 axillary lymph nodes and in internal mammary lymph nodes, with micrometastases or macrometastases detected by sentinel lymph node biopsy but not clinically detectedb |

pN2 | Metastases in 4–9 axillary lymph nodes or in clinically detectedc internal mammary lymph nodes in the absence of axillary lymph node metastases |

pN2a | Metastases in 4–9 axillary lymph nodes (at least 1 tumour deposit >2.0 mm) |

pN2b | Metastases in clinically detectedc internal mammary lymph nodes in the absence of axillary lymph node metastases |

pN3 | Metastases in ≥10 axillary lymph nodes; or in infraclavicular (level III axillary) lymph nodes; or in clinically detectedc ipsilateral internal mammary lymph nodes in the presence of ≥1 positive level I, II axillary lymph nodes; or in >3 axillary lymph nodes and in internal mammary lymph nodes, with micrometastases or macrometastases detected by sentinel lymph node biopsy but not clinically detectedb; or in ipsilateral supraclavicular lymph nodes |

pN3a | Metastases in ≥10 axillary lymph nodes (at least 1 tumour deposit >2.0 mm); or metastases to the infraclavicular (level III axillary) nodes |

pN3b | Metastases in clinically detectedc ipsilateral internal mammary lymph nodes in the presence of ≥1 positive axillary lymph nodes; or in >3 axillary lymph nodes and in internal mammary lymph nodes, with micrometastases or macrometastases detected by sentinel lymph node biopsy but not clinically detectedb |

pN3c | Metastases in ipsilateral supraclavicular lymph nodes |

Histologic grade (G) | |

GX | Grade cannot be assessed |

G1 | Low combined histologic grade (favourable) |

G2 | Intermediate combined histologic grade (moderately favourable) |

G3 | High combined histologic grade (unfavourable) |

Tumour Size (pT)

It is recommended to perform the following:

Measure at least two tumour dimensions; however, indicate only the size of the invasive lesion, at its greatest dimension.

Always verify the tumour size under the microscope; in case of difference between the tumour sizes determined during the gross and at the microscopic examination, the size determined by microscopy will be taken into account for staging (pT).

In case of multiple tumours, the tumour size should not be determined as the sum of individual tumour sizes; the individual tumour sizes should be reported, and the most voluminous tumour will be taken into account for staging (pT). The issue of T staging in multifocal disease is somewhat controversial, and using such a system it is recognized that prognosis may be less accurate as this system underestimates tumour volume [37].

Lymph Node Status (pN)

The strong prognostic impact of LN involvement and of the number of involved LNs is well known. In the new TNM classification, involvement of the subclavicular LN corresponds to N3 status (instead of being categorized as M1, as in the previous classification). The pathology report should contain the number of involved nodes among all the excised nodes and, eventually, the size of the largest metastasis. In case of SLN excision, the node is cut at three levels at least. The use of IHC to detect micrometastases or isolated tumour cells is not standardized and depends upon local guidelines.

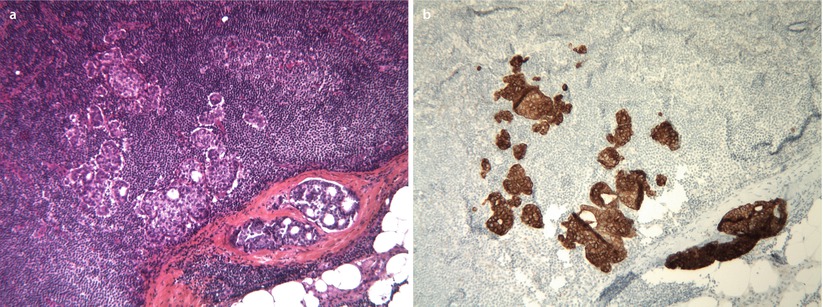

In the new TNM classification, a LN micrometastasis is defined as the presence of a metastatic deposit of 0.2–2.0 mm size at its greatest dimension (◘ Figs. 15.6a and 15.6b). Smaller metastatic foci (less than 0.2 mm) or single cancer cells are classified as pN0(i+) if they are confirmed by IHC or (mol+) if the evaluation of LN involvement is made by the molecular biology method OSNA® (one-step nucleic acid amplification, Sysmex, Japan) [26]. The new TNM system thus provides a classification of LN micrometastases, which have been increasingly detected since the SLN technique was implemented. However, the prognostic impact of metastatic microfoci, detected by IHC only, remains controversial.

Fig. 15.6

a Micrometastasis in a lymph node, H&E staining. b Micrometastasis in a lymph node, immunohistochemistry for pan-cytokeratin

Tumour Histopathological Subtype

Breast cancer histological subtype is determined according to the fourth WHO classification of breast tumours [1], details of which are presented in ◘ Table 15.3.

Table 15.3

2012 WHO classification of tumours of the breast

Invasive breast carcinoma |

Invasive carcinoma of no special type (NST) (formal ductal carcinoma and rare variants, pleomorphic carcinoma, carcinoma with osteoclast-like stromal giant cells, carcinoma with choriocarcinomatous features, carcinoma with melanotic features) |

Special types |

Invasive lobular carcinoma |

Classic lobular carcinoma |

Solid lobular carcinoma |

Alveolar lobular carcinoma |

Pleomorphic lobular carcinoma

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|