The individual organs within the genital tract make up an extended müllerian system that can give rise to a wide variety of histologically similar tumors. Because of this extended müllerian system, tumor classification and assignment of primary site can be problematic. This chapter provides an overview of the main tumors that are encountered in the female genital tract, emphasizing key histopathologic features and pertinent ancillary diagnostic studies.

To maximize the information provided by pathologic examination, it is important that the treating clinician understand basic concepts of gynecologic oncologic pathology. It is similarly important for the pathologist to understand basic clinical, radiologic, and serologic data. The integration of clinical, radiologic, and pathologic information is central to intraoperative evaluation, and ultimately to treatment planning, and it occurs best within the framework of the multidisciplinary tumor board conducted in most major cancer centers.

Cervix

Squamous Lesions of the Cervix

Terminology

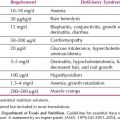

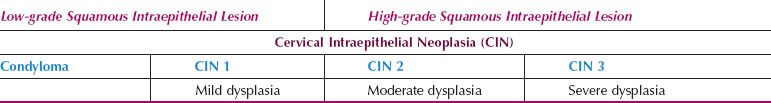

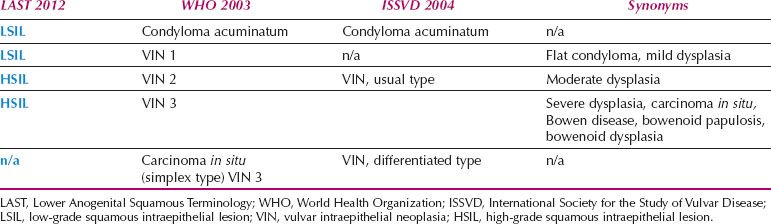

Historically, there have been several systems for classifying preneoplastic lesions of the cervix, so it is useful to be familiar with all the systems because the terms can be used interchangeably (Table 5.1). Over the years, the classification systems have moved toward fewer, more clinically relevant categories. In 2012, the College of American Pathologists (CAP) and the American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology (ASCCP) sponsored a consensus conference to propose uniform terminology for HPV-related squamous intraepithelial lesions and early invasive carcinoma (1). The Lower Anogenital Squamous Terminology (LAST) Project recommended a two-tiered nomenclature system—low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (LSIL) and high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (HSIL)—which can be further qualified by the grade of intraepithelial neoplasia (-IN). The SIL terminology parallels the Bethesda system, which has been in use since 1988, and was developed for providing uniform diagnostic terminology for cervical cytologic specimens. The LSIL category encompasses condyloma and CIN 1, whereas the HSIL category encompasses CIN 2 and CIN 3. CIN 1 is equivalent to mild dysplasia, CIN 2 to moderate dysplasia, and CIN 3 to severe dysplasia and carcinoma in situ. The LAST recommendations apply across the anogenital tract for HPV-related preneoplastic squamous lesions.

Table 5.1 Terminology for Cervicovaginal Squamous Intraepithelial Lesions

Low-grade Squamous Intraepithelial Lesion

There are three main subtypes of LSIL. Flat condylomas lack the exophytic growth pattern and are more frequently associated with intermediate and high-risk HPV types. These are the most common in the cervix. Condyloma acuminatum is the classic genital wart with an exophytic growth pattern. It is typically associated with low-risk HPV types 6 and 11. Immature condylomas are the least common and exhibit a filiform, papillary growth pattern; they are associated with low-risk HPV types.

LSIL is characterized by thickened mucosa with enlarged, dark cells that have low nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratios in the upper layers (Fig. 5.1). Binucleation can be seen in 90% of LSIL, and when the nuclei are surrounded by an irregularly shaped and sharply punched out halo, they are known as koilocytes. However, binucleation and halos can be seen as part of a reactive process. With reactive change, the nucleus is minimally enlarged, not hyperchromatic, and the halo is less distinct, round, and uniform. Glycogen vacuoles can appear as round, uniform halos. In addition, LSIL can be mimicked by a squamous papilloma (also known as an ectocervical or fibroepithelial polyp). Squamous papillomas lack koilocytes, and have central fibrovascular cores that are not typical of condylomas.

Figure 5.1 Low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (mild dysplasia, CIN 1). The mucosa is thickened with dysplastic cells and koilocytes in the upper layers.

The ASCUS-LSIL Triage Study investigated interobserver variability in the diagnosis of squamous intraepithelial lesion (SIL) on biopsy (2). More than 2,700 cervical biopsies and loop electrosurgical excision procedure (LEEP) specimens were examined by one of two staff pathologists at one of four centers across the United States, and reviewed by one of four quality control (QC) pathologists. There was agreement on the diagnosis of LSIL in 43% of cases, but 41% of the cases diagnosed by the staff pathologists as LSIL were downgraded by the QC pathologists to negative. Most of the downgraded cases were positive for high-risk HPV, raising the question of which diagnosis was correct. The significance of this finding was not addressed by the study.

High-grade Squamous Intraepithelial Lesion

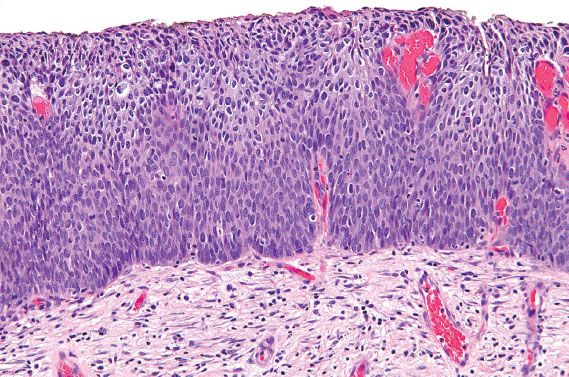

HSIL is characterized by atypical, dark cells with high nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratios, which involve one-third to two-thirds of the epithelium in cases of CIN 2 (Fig. 5.2), or more than two-thirds in cases of CIN 3 (Fig. 5.3). The involved mucosa is notable for disorderly arrangement of cells, with loss of polarity and crowding. Mitotic figures in the upper half of the mucosa are commonly identified.

Immature squamous metaplasia and atrophy can be difficult to distinguish from HSIL, because they are also characterized by cells with high nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratios. However, the nuclei in squamous metaplasia and atrophy should lack crowding and appear uniform, with smooth nuclear membranes. Mitotic figures can be seen near the basal layer, but not in the upper half of the mucosa. In indeterminate cases, immunohistochemical staining for p16, a surrogate marker for high-risk HPV, can be helpful (3). In some cases, for various reasons (e.g., tangential sectioning, small dissociated fragments, cautery artifact), a distinction cannot be made between LSIL and HSIL. These are best characterized as SIL of indeterminate grade.

The ALT study found good reproducibility for the histologic diagnosis of CIN 3, with concordance in 72.8% of cases (4). The reproducibility for the diagnosis of CIN 2 was significantly lower at 43.4%. A separate joint National Cancer Institute (NCI)-Costa Rica study reported similar disparities in the rates of agreement: 13–31% for CIN 2 and 81–84% for CIN 3 (5). Recognizing that CIN 2 is an equivocal diagnosis that encompasses both CIN 1 and CIN 3, the CAP-ASCCP LAST Project recommended the use of p16 immunohistochemistry when considering a diagnosis of CIN 2. Strong and diffuse block positive p16 results support a diagnosis of HSIL (CIN 2), while negative p16 results support a LSIL (CIN 1) or a non-HPV–associated lesion (1). The presence of block positive p16 correlates with the presence of high-risk HPV that has integrated into the host genome, and correlates with a diagnosis of a precancerous lesion. Since LSIL can exhibit block positive p16 expression, grading of dysplasia is based primarily on H&E morphology.

Figure 5.2 High-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (moderate dysplasia, CIN 2). Dysplastic cells with high nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratios involve less than two-thirds of the mucosa.

Figure 5.3 High-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (severe dysplasia, CIN 3). The squamous mucosa is notable for full thickness atypia and extension of the dysplastic cells down into endocervical glands.

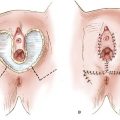

Squamous Cell Carcinoma

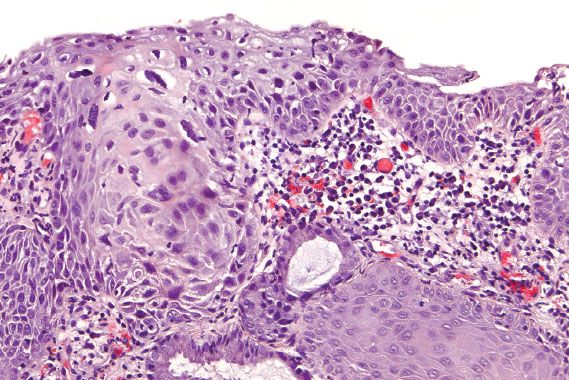

Cervical squamous cell carcinomas can be subdivided into two main groups: superficially invasive carcinomas and invasive carcinomas. Superficially invasive carcinoma (FIGO* stage IA1) is defined as microscopic disease with ≤3 mm of stromal invasion and ≤7 mm of horizontal extent. For accurate measurements, the entire lesion needs to be visible, and requires negative surgical margins. Although lymphatic-vascular invasion (LVI) is acknowledged as a poor prognostic factor, the presence or absence of LVI does not change the FIGO stage. The depth of invasion is measured from the basement membrane at the point of invasion to the deepest invasive focus (Fig. 5.4). Morphologically, superficially invasive carcinoma is characterized by jagged fingers extending from the base of HSIL into the submucosa, and surrounded by chronic inflammation and loose, fibroblastic stroma (i.e., desmoplasia). Often at the point of invasion, the neoplastic cells become more differentiated and have abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm that may be keratinizing. Superficially invasive carcinoma can be difficult to distinguish from HSIL, especially when HSIL involves endocervical glands, or is associated with previous biopsy site changes. Examining multiple level sections of the same focus can be helpful.

Squamous cell carcinomas that are clearly invasive can be keratinizing or nonkeratinizing, and range from well differentiated to poorly differentiated. Well- to moderately differentiated invasive squamous cell carcinoma is characterized by cohesive nests and sheets of neoplastic cells with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm and distinct cell borders (Fig. 5.5). Keratin pearl formation, central keratinization, and necrosis within nests may also be identified. With poorly differentiated carcinomas, keratinization may be minimal or absent, and they may be difficult to distinguish from other types of poorly differentiated carcinomas (e.g., adenocarcinoma). Grade and type have not been found to be prognostically significant. Instead, depth of invasion, lymphatic or vascular invasion, and size are important prognostic variables.

Human Papilloma Virus

Human papilloma virus (HPV) DNA has been detected in virtually all cases of cervical dysplasia and carcinoma and is considered to be a necessary, but not sufficient cause for the development of the vast majority of invasive cervical carcinomas. Although a variety of HPV types may infect epithelial cells, the risk of oncogenic transformation is most strongly linked to several specific high-risk types. In 2003, a large epidemiologic study by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) pooled data from nine countries, and identified 15 high-risk HPV types (16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58, 59, 68, 73, and 82), 3 probable high-risk types (26, 53, and 66), and 12 low-risk types (6, 11, 40, 42, 43, 44, 54, 61, 70, 72, 81, and CP6108). The IARC met again in 2005 to reassess the carcinogenicity of HPV, and revised the original list of high-risk types to include 13 types: 16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58, 59, and 66 (6). Most investigators now believe that persistent infection with high-risk HPV types is associated with the subsequent development of high-grade dysplasia and invasive carcinoma (7). A substantial proportion of LSIL is associated with infection by high-risk HPV types, but many infections are transitory (7,8).

Figure 5.4 Superficially invasive squamous cell carcinoma of the cervix. Invasion is measured from the basement membrane at the point of invasion (upper arrow) to the deepest invasive focus (lower arrow). FIGO* Stage IA1 cervical cancer is defined by a depth of invasion ≤3 mm and horizontal extent ≤7 mm in a specimen with negative margins.

Figure 5.5 Invasive squamous cell carcinoma of the cervix, moderately differentiated keratinizing. Keratinization and necrosis within nests of malignant squamous cells are present.

Cervicovaginal Cytology–Pap Testing

Specimen Preparation Methods

There are two main specimen types for cervicovaginal cytology: conventional smear and liquid-based preparation. Conventional smears involve directly smearing material onto a glass slide, and immediately fixing the specimen with ethanol. The advantages of conventional smears are their low cost, and the lack of need for specialized equipment to process specimens. The disadvantages are lack of uniformity in specimen preparation, and unsatisfactory smears because of obscuring inflammation, blood, or thick areas in the smear.

Liquid-based preparations involve placing the cytologic material in a liquid fixative instead of directly smearing it on a glass slide. The two most commonly used are ThinPrep (Hologic, Bedford, MA) and SurePath (BD Diagnostics, Burlington, NC). ThinPrep uses a methanol-based fixative and a filter preparation for making the slide. SurePath uses an ethanol-based fixative and a Ficoll gradient. SurePath employs a detachable head for the collection device so that the entire specimen can be submitted for processing. The advantages of liquid-based preparations are uniformity in slide preparation and fewer unsatisfactory specimens. The disadvantages are significantly higher cost, and the necessity for specialized processing equipment for each liquid-based method.

Who Signs Out Pap Tests?

Cervicovaginal cytologic specimens are predominantly screened by board-certified cytotechnologists. In some small laboratories, the primary screening of the slides is performed by a pathologist. If the Pap test is negative for an intraepithelial lesion or malignancy and lacks reactive or reparative changes, the final report can be issued by the cytotechnologist. Quality control review by a second senior cytotechnologist or a pathologist should be performed on at least 10% of all negative cases, and on all cases for patients with a history of an abnormal Pap test. If any reactive, reparative, or epithelial abnormalities are found, the slide must be reviewed by a pathologist who will issue the final report.

The Clinical Laboratory Improvement Act of 1988 set limits on the number of Pap tests that can be reviewed by a cytotechnologist in a 24-hour period. The nationwide limit is 100 nonimaged or 200 imaged slides per day, but individual states can set lower limits (e.g., 80 nonimaged or 160 imaged slides in California). There is a requirement that all pathologists and cytotechnologists who interpret Pap tests pass an annual proficiency test.

The Bethesda System

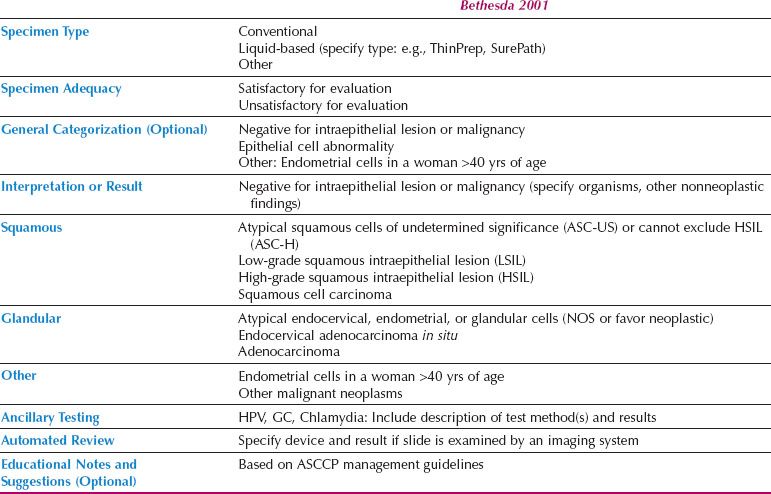

In 1988, the National Cancer Institute sponsored a workshop in Bethesda, Maryland, to develop a uniform diagnostic terminology for Pap tests. The resulting classification system underwent multiple revisions and the system currently in use is Bethesda 2001 (9) (Table 5.2).

According to the Bethesda system, the Pap test report should include the following categories: specimen type (e.g., conventional, liquid based, or other), specimen adequacy, and interpretation or result. A general categorization section and educational notes and suggestions are optional. If automated screening is performed (e.g., ThinPrep Imager or BD FocalPoint), the device and result should also be reported. If ancillary testing is performed, the results may be indicated in the Pap test report or reported separately.

Specimen adequacy is divided into “satisfactory for evaluation” and “unsatisfactory for evaluation.” The presence or absence of transformation zone cells (i.e., endocervical cells or squamous metaplastic cells) and quality indicators (e.g., obscuring blood or inflammation, scant cellularity) is indicated under the umbrella of “satisfactory for evaluation.” Specimens can be unsatisfactory for a variety of reasons, and this will be indicated on the report. Some specimens are rejected and not processed; these are usually the result of a broken slide or empty collection vial. Others are found to be unsatisfactory after processing and examination of the slide. A common cause of unsatisfactory ThinPrep specimens is the use of lubricants containing carbomers or carbopol polymers when obtaining the sample. Cytyc has distributed a nonexhaustive list of lubricants that are less likely to interfere with processing (Table 5.3). Another common cause of unsatisfactory specimens is obscuring blood. Although liquid-based systems can remove blood from the sample, the ThinPrep system is able to handle less blood than the SurePath Ficoll gradient.

Table 5.2 2001 Bethesda System

Squamous Cell Abnormalities

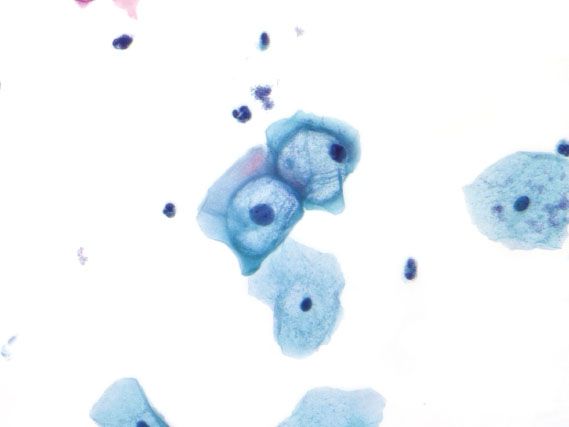

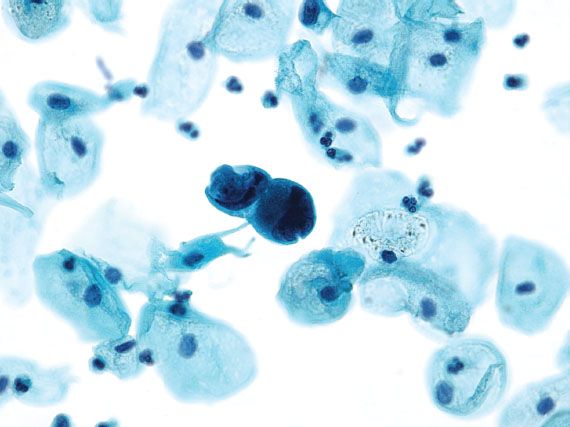

LSIL in cervical cytology specimens is characterized by enlarged, dark nuclei (more than three times the size of an intermediate cell nucleus), with irregular, thickened nuclear membranes. When the cells are binucleated and surrounded by a sharply defined, irregularly shaped halo with a peripheral rim of thickened cytoplasm, the cell is known as a koilocyte (Fig. 5.6). Although koilocytes are pathognomonic for a diagnosis of LSIL, they are not required. LSIL can be diagnosed based on cells with enlarged, dark, irregular nuclei and no cytoplasmic halo. Koilocytes can be mimicked by prominent glycogen vacuoles or inflammatory halos (Fig. 5.7). In these cases, the area of perinuclear clearing is not sharply demarcated, and tends to be round and regular with the nucleus centrally located. When the findings fall short of LSIL, the diagnosis of atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance (ASC-US) is used (Fig. 5.8). Usually, this is because one of the nuclear features is lacking: The nuclei may be not quite large enough (2.5 to 3 times the size of an intermediate cell nucleus), dark enough, or irregular enough.

Table 5.3 Lubricants Less Likely to Interfere with ThinPrep Samples

Figure 5.6 Low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion. Koilocytes have sharply delineated, irregular halos and multiple, dark nuclei with irregular nuclear borders. (Papanicolaou stain)

Figure 5.7 Inflammatory halos. Perinuclear clearing with a centrally located nucleus and hazy edges can be seen with infections (e.g., trichomonas) and can be mistaken for koilocytes. (Papanicolaou stain)

Figure 5.8 Atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance (ASC-US). The nucleus is 2.5 times the size of the intermediate cell nucleus, and the nuclear membranes are smooth. (Papanicolaou stain)

HSIL is characterized by cells with dark nuclei, irregular nuclear membranes, and high nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratios (Fig. 5.9). The dysplastic cells can occur singly, in sheets, or as syncytial aggregates. The chromatin may range from coarse to bland, and the cytoplasm from delicate to dense. The nuclei vary in size, and are frequently smaller than those seen with LSIL. With liquid-based preparations, dispersed abnormal single cells are more common than aggregates. In addition, with ThinPrep, the nuclei may not be dark; the diagnosis relies on finding single cells with irregular nuclear membranes and high nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratios.

Mimics of HSIL include squamous metaplasia, atrophy, repair, endometrial cells, histiocytes, and endocervical cells. Atrophy and squamous metaplasia can be especially difficult to distinguish from HSIL. With atrophic changes, the basal and parabasal cells have high nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratios with enlarged, dark nuclei, and the background can resemble tumor diathesis (Fig. 5.10). The distinction from HSIL relies on finding smooth nuclear membranes, flat monolayer sheets, and lack of variability in the nuclear size and shape. Squamous metaplastic cells have high nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratios and dense cytoplasm, but smooth nuclear membranes. If the cytologic features fall short of a diagnosis of HSIL, the diagnosis of “atypical squamous cells–cannot exclude HSIL (ASC-H)” is used. If dysplastic cells are clearly present but do not quite meet criteria for HSIL, then the changes are characterized as “LSIL cannot exclude HSIL.”

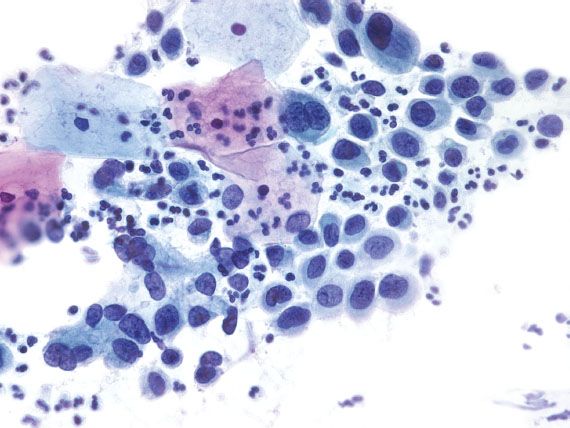

The cytologic diagnosis of squamous cell carcinoma implies invasive carcinoma, because carcinoma in situ is encompassed within the category of HSIL. Keratinizing squamous cell carcinoma has single cells with dense, dark nuclei and dense, orangeophilic (i.e., orange-colored) cytoplasm. Nonkeratinizing squamous cell carcinoma has syncytial aggregates and single cells with coarse chromatin and poorly defined cell borders with delicate basophilic (i.e., blue-colored) cytoplasm. Macronucleoli and tumor diathesis (i.e., necrosis, degenerating blood, inflammation) can be seen with both, but more frequently with nonkeratinizing squamous cell carcinoma. With liquid-based preparations, tumor diathesis is seen as necrotic material clinging to the edges of cell groups, and is less apparent than on conventional smears where it is spread across the background (Fig. 5.11). Squamous cell carcinoma can be difficult to distinguish from HSIL, because there is a significant morphologic overlap between these two entities. Because keratinization can be seen with both, the findings of macronucleoli and tumor diathesis are more reliable indicators of squamous cell carcinoma, but are not always present. For both HSIL and squamous cell carcinoma, the next step is colposcopy with biopsy, which will provide material for more definitive assessment of invasive carcinoma.

Figure 5.9 High-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion. The dysplastic cells have dark nuclei with focal nuclear membrane irregularities and high nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratios. (Papanicolaou stain)

Figure 5.10 Atrophy. Atrophic vaginitis is characterized by sheets of parabasal cells and an inflammatory background that can mimic squamous cell carcinoma. (Papanicolaou stain)

Figure 5.11 Squamous cell carcinoma. Necrosis in liquid-based preparations is characterized by granular debris that clings to the edges of tumor cell clusters. (Papanicolaou stain)

Glandular Cell Abnormalities

The diagnosis of “atypical glandular cells” accounts for less than 1% of all Pap tests. Significant disease is present in 9–38% of cases, with HSIL the most common abnormal finding (10). Other findings include endocervical adenocarcinoma in situ (AIS), endocervical adenocarcinoma, endometrial pathology including carcinoma, and extrauterine carcinoma. Postmenopausal women have a higher rate of abnormality, with a significant cervical or endometrial abnormality found in more than 30% of cases.

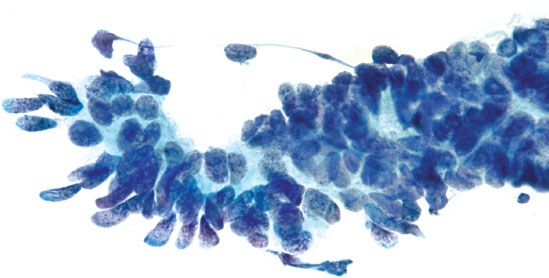

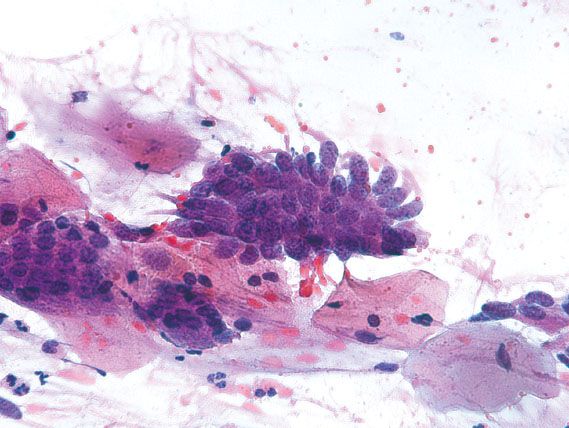

Endocervical AIS is characterized by enlarged, elongated nuclei, with irregular nuclear membranes and coarse chromatin arranged radially as rosettes or in strips as crowded palisades (Fig. 5.12). When the cytoplasm is partially stripped away, the palisading nuclei can resemble an array of feathers. This feature is referred to as feathering, and is considered characteristic of AIS. Mitotic figures are commonly present.

Endocervical AIS can be closely mimicked by tubal metaplasia, direct sampling of the endometrium, and HSIL involving endocervical glands. Tubal metaplasia is distinguished by the lack of nuclear crowding and smooth nuclear membranes. The presence of cilia is characteristic but not always seen. Direct sampling of the endometrium can yield strips and sheets of atypical glandular cells with feathering, rosette formation, and frequent mitotic figures. Identifying small, tightly cohesive endometrial stromal cells can help in the distinction from AIS. Sampling of endometrial glands can occur as the result of cervical endometriosis, or inadvertent sampling of the lower uterine segment or endometrial cavity (Fig. 5.13). The latter occurs more frequently in patients who have a shortened cervix because of previous LEEP or cone biopsy. The presence of glands embedded in stroma should raise the possibility of direct endometrial sampling. HSIL involving endocervical glands can be distinguished from AIS by the lack of palisading, presence of single cells with high nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratios and irregular nuclear membranes, or evidence of keratinization. AIS and HSIL can coexist. If the features fall short of a diagnosis of AIS, depending on the degree of atypia present, the following Bethesda diagnoses may be used: “Atypical endocervical cells, not otherwise specified (NOS)” or “Atypical endocervical cells, favor neoplastic.” The latter diagnosis is associated with a higher likelihood of finding a clinically significant lesion on biopsy.

Figure 5.12 Endocervical adenocarcinoma in situ. Palisading nuclei stripped of cytoplasm (“feathering”) is a characteristic feature. The nuclei are enlarged and elongated with coarse chromatin. (Papanicolaou stain)

Figure 5.13 Endometriosis. Direct sampling of endometrial glands in cervical endometriosis can mimic endocervical adenocarcinoma in situ. The smooth nuclear membranes and lack of nuclear crowding support a benign process. (Papanicolaou stain)

Figure 5.14 Endometrial carcinoma. Three-dimensional papillary clusters of cells with enlarged nuclei. (Papanicolaou stain)

Adenocarcinomas most commonly originate from the endocervix or endometrium, but malignant glandular cells on cervical cytology may represent spread from an extrauterine source (e.g., ovary, breast, stomach, colon, kidney, or bladder). Invasive endocervical adenocarcinomas resemble AIS, but are distinguished by the presence of a tumor diathesis in the background. Endometrial carcinoma is characterized by three-dimensional groups or papillary clusters of cells with enlarged nuclei, and often vacuolated cytoplasm (Fig. 5.14). Intracytoplasmic neutrophils are common. When the tumor cells have large cytoplasmic vacuoles and are associated with psammoma bodies, the findings are suggestive of a serous carcinoma. Adenocarcinoma cells in a clean background or with unusual morphology that is not typical of a uterine primary raise the possibility of metastatic disease (Fig. 5.15).

The diagnosis of atypical endometrial cells is used when endometrial cell clusters show mild nuclear enlargement, vacuolated cytoplasm, or cytoplasmic neutrophils. If it cannot be determined whether the atypical cells are endocervical or endometrial in origin, the diagnosis of atypical glandular cells (NOS) or atypical glandular cells, favor neoplastic can be used.

Other

The diagnosis of “endometrial cells in a woman 40 years of age and older” is used when benign-appearing exfoliated endometrial stromal or glandular cells are identified in a cervical cytologic specimen from a woman aged 40 or older. The age cutoff was set by the Bethesda system 2001 because menstrual data, menopausal status, hormonal therapy, and clinical risk factors are frequently unknown to the laboratory. For asymptomatic, premenopausal women, no further studies are recommended. Endometrial sampling is recommended for symptomatic premenopausal women and all postmenopausal women (10).

Ancillary Testing

HPV testing became routine after the ASCUS LSIL Triage (ALT) Study (11) and the publication of the American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology (ASCCP) Consensus Guidelines for the Management of Women with Cervical Cytological Abnormalities. Initially, Digene Hybrid Capture II (HC2) was the only commercially available HPV test, and had the additional distinction of being the assay used in the ALT study. In the intervening time, several different assays that use multiple different methodologies have become commercially available.

Figure 5.15 Metastatic breast carcinoma. Adenocarcinoma cells in a background without inflammation and necrosis raise the possibility of spread from an extrauterine source. (Papanicolaou stain)

There are four United States Food and Drug Administration (US FDA)-approved HPV assays for use in ASC-US triage and for co-testing in women over the age of 30: HC2 (Qiagen), Cervista HPV HR (Hologic), cobas HPV Test (Roche), and Aptima HPV Assay (GenProbe). The high-risk probes for all four assays target high-risk HPV types 16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58, 59, and 68. The probes for Cervista, cobas, and Aptima also target HPV type 66, which was classified as high risk by the IARC in 2005. Although the HC2 high-risk probe does not directly target HPV 66, studies showed that HPV 66 is detected through cross-reactivity. One of the main criticisms of HC2 is decreased specificity because of cross-reactivity, but the benefit of cross-reactivity is increased clinical sensitivity. As exemplified by HPV 66, cross-reactivity can allow for the detection of HPV types not classified as high risk.

The use of HPV genotyping has been incorporated into the ASCCP Consensus Guidelines since HPV types 16 and 18 were recognized as more carcinogenic and responsible for the majority of cervical cancers. The cobas HPV Test screens for 14 high-risk HPV types, and specficially identifies HPV types 16 and 18. Cervista has a separate HPV 16/18 probe that can be used for genotyping if the initial Cervista HPV HR screen is positive. HPV testing was initially validated by the ALT study using HC2; the newer assays are required to show similar or better test characteristics. In comparison with HC2, the other three systems exhibit similar sensitivity and offer the advantage of including an internal positive control.

Positive results with HC2 testing for high-risk HPV have been reported in many patients who have no cytologic or histologic evidence of dysplasia. False positive results with HC2 can occur as the result of cross-reactivity or signal leak. De Cremoux et al. (12) reported a false positive rate of 6.2%, with 1.9% because of cross-reactivity and 4.3% because of signal leak. Cross-reactivity with high-risk HPV DNA can occur in cases that have very high loads of low-risk HPV; similar cross-reactivity with low-risk types can occur with high loads of high-risk HPV. In addition, the chemiluminescent signal in cases with high viral loads can lead to false positive results in contiguous samples because of leaking of the signal.

HC2 results are reported as positive, negative, or equivocal based on the assigned cutoff of 1.0 RLU/PC. Although HC2 testing has been shown to have good interlaboratory reproducibility, there is poor reproducibility near the cutoff point of 1 RLU/PC (13). In a significant portion of cases with borderline positive HC2 results, PCR analysis for HPV is negative (14). Cases that are near the cutoff point are reported as equivocal because they may represent a false positive result. The newer HPV assays exhibit less cross-reactivity and equivalent or better specificity than HC2.

Automated Screening

The main impetus behind developing automated screening systems has been to increase productivity and improve quality. Both ThinPrep and SurePath have imaging systems that can be used with their liquid-based preparations. The ThinPrep Imaging System was approved by the US FDA in 2003 for dual review of ThinPrep cervical cytology slides. After the imaging system screens the slide, the cytotechnologist reviews 22 selected fields of view. If any abnormal cells are seen, the slide is manually rescreened by the cytotechnologist. Studies have shown that the ThinPrep system has equivalent or better sensitivity than manual screening for the detection of LSIL and HSIL, and higher specificity for the diagnosis of HSIL (15).

The BD FocalPoint Slide Profiler has been US FDA approved for primary screening of SurePath or conventional cervical cytologic slides. It functions as a triage device, allowing a portion of slides to be archived with no further review by a cytotechnologist, and identifying cases that are more likely to contain significant abnormalities, requiring further review. The BD FocalPoint GS Imaging System is an US FDA-approved location-guided screening system that can be used in conjunction with the Slide Profiler. The guided screener will direct the cytotechnologist to the fields of view containing the abnormal areas detected by image analysis.

Glandular Lesions of the Cervix

Terminology

A variety of terms have been used to describe preinvasive glandular lesions of the cervix, including atypia, dysplasia, and AIS. Unlike cervical squamous lesions, cervical glandular dysplasia is a poorly defined and controversial entity. Glandular lesions that exhibit some but not all the features of adenocarcinoma in situ have been associated with in situ and invasive adenocarcinoma, but the diagnostic criteria, clinical implications, prevalence, and progression rate of these lesions are not uniformly agreed upon (16).

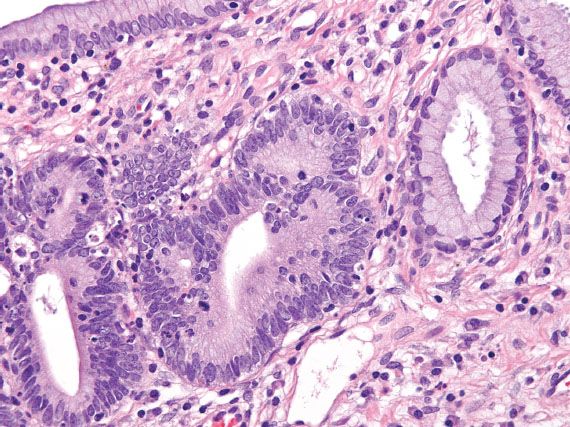

Adenocarcinoma In Situ

The histologic diagnosis of AIS requires unequivocal dysplastic changes, which are typically manifested by low-power basophilia, nuclear hyperchromasia with either fine or coarsely granular chromatin, nuclear apoptotic or karyorrhectic debris, apical mitotic figures, and loss of polarity (which may be subtle) (Fig. 5.16). The involved glands exhibit a lobular architecture that may appear more pronounced than adjacent uninvolved endocervical glands, but irregular infiltration into the stroma is absent. Partial glandular involvement is common. A superficial form of AIS has been described in the superficial columnar mucosa featuring similar cytologic alterations, but less pronounced atypia. This lesion is thought to occur more commonly in a younger age group (mean, 26 years) and so is interpreted as an “early” form of AIS (17).

A variety of processes mimic AIS, including tubal or tuboendometrial metaplasia, endometriosis, reactive endocervical cells, and several endocervical cell alterations that do not necessarily appear to represent a reactive process (18). These latter alterations often pose the most diagnostic difficulty, and are classified on the basis of the abnormality present: endocervical glandular hyperplasia, mitotically active endocervical mucosa, stratified endocervical mucosa, and atypical oxyphilic metaplasia.

Biomarkers, particularly a combination of Ki-67 and p16, are helpful in the differential diagnosis of AIS. In general, strong, diffuse expression of p16 in conjunction with increased Ki-67 is more commonly associated with AIS, whereas weak or focal p16 expression with or without increased Ki-67 is more supportive of an AIS mimic (19). Exceptions occur, so it is important to be thoroughly aware of the variant expression patterns of these markers in the individual lesions, in order to prevent overinterpretation on the basis of staining patterns alone (20).

Invasive Adenocarcinoma

The diagnosis of invasive cervical adenocarcinoma can be very difficult in early or superficially invasive lesions, and in limited (superficial) biopsy specimens. Unlike squamous carcinoma of the cervix, invasion may not be associated with a significant stromal reaction; in these instances, identification of invasion is based on the presence of significant glandular irregularity, an infiltrative glandular pattern, and the presence of enlarged, complex neoplastic glandular structures deep to the normal endocervical crypts (Fig. 5.17).

Figure 5.16 Adenocarcinoma in situ of the cervix. In situ carcinoma exhibits nuclear hyperchromasia, stratification, irregular chromatin, and apical mitotic figures. A normal endocervical gland is present on the right.

Because of the difficulties in diagnosing early invasive lesions, the concept of “microinvasive adenocarcinoma” is not as well accepted as it is for superficially invasive squamous cell carcinoma; nevertheless, a maximum depth of invasion of 3 mm with negative margins and no lymphovascular invasion is considered by most clinicians as the upper limit for consideration of conservative management. Measurements are made from the surface and expressed in millimeters.

Invasive adenocarcinoma of the usual or endocervical type accounts for 60–70% of cervical adenocarcinomas. Two variants—adenoma malignum (minimal deviation adenocarcinoma) and villoglandular adenocarcinoma—are very uncommon, but the source of frequent diagnostic problems. Other named histologic subtypes include serous, clear cell, endometrioid, mesonephric, intestinal type, signet-ring cell type, adenosquamous, adenoid basal, adenoid cystic, and adenocarcinoma admixed with neuroendocrine carcinoma, and undifferentiated carcinoma (18,21). Only those with distinctive clinical or differential diagnostic problems that affect prognosis or treatment are discussed.

Minimal Deviation Carcinoma—Adenoma Malignum

This tumor, which is characterized by a deceptively benign histologic appearance, accounts for <10% of all cervical adenocarcinomas. Patients present with irregular bleeding, diffuse cervical enlargement, or vaginal mucus discharge. Most minimal deviation carcinomas exhibit a gastric mucin phenotype. An association with Peutz–Jeghers syndrome has been reported (21). A wide age range has been reported, but virtually all patients are older than 20 years of age.

Microscopically, the tumor features cystically dilated, irregular (claw-shaped) glands with minimal cytologic atypia, and minimal stromal reaction (Fig. 5.18). The diagnosis is most easily established by careful search for foci of cytologic atypia, stromal reaction, or conventional-type adenocarcinoma. This tumor can replace normal endocervical and endometrial glandular tissue, mimicking mucinous metaplasia in uterine curettings and biopsy. Intracytoplasmic carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) staining may be helpful in some cases, but not all adenoma malignum carcinomas are CEA positive and normal endocervical glands may express CEA on occasion, although usually only along the surface (glycocalyx). These carcinomas do not stain for p16.

Figure 5.17 Invasive adenocarcinoma of the cervix. Deeply infiltrative glands are irregular in contour and surrounded by edematous stroma. (top, low power; bottom, high power)

Villoglandular Carcinoma

This tumor occurs predominantly in young women and is characterized by villoglandular architectural growth pattern and low nuclear grade. These tumors have a good prognosis, but only if they are exophytic with minimal or no invasion (Fig. 5.19). An association with HPV has been reported and these tumors are p16 positive.

Figure 5.18 Minimal deviation adenocarcinoma (adenoma malignum). Large, irregular mucinous glands typically show bland or minimally atypical cytologic features. (top, low power; bottom, high power)

Clear Cell Carcinoma

Clear cell carcinoma may occur in young (diethystilbestrol exposure in utero) or older women, and may arise in the ectocervix (typically, associated with diethystilbestrol exposure) or endocervix. A variety of patterns—including tubulocystic or glandular, solid, and papillary—may be seen (21).

Figure 5.19 Villoglandular adenocarcinoma of cervix. Slender, elongated villi are lined by well-differentiated epithelium with an exophytic growth pattern. This tumor is associated with a good prognosis, provided there is minimal or no cervical stromal invasion. (top, low power; bottom, high power)

Mesonephric Carcinoma

Mesonephric remnants may develop hyperplasia and carcinoma; often a spectrum of these changes is seen in the carcinomas (21). The carcinomas often pose significant diagnostic difficulty because of their lateral and deep location within the cervix. There may be no surface component. Ductal, retiform, tubular, solid, and spindle patterns may be seen in the carcinomas. Most have low to moderate nuclear grade, so some cases may be difficult to distinguish from florid mesonephric hyperplasia. The distinction is often based on loss of lobular architecture and infiltrative pattern. Diagnosis of higher-grade mesonephric adenocarcinoma is based on identification of residual normal or hyperplastic mesonephric tubules with their characteristic eosinophilic luminal material. Prognosis is uncertain because of the limited numbers of cases, but probably similar to usual endocervical adenocarcinoma. These tumors are not known to be associated with HPV and most are p16 negative.

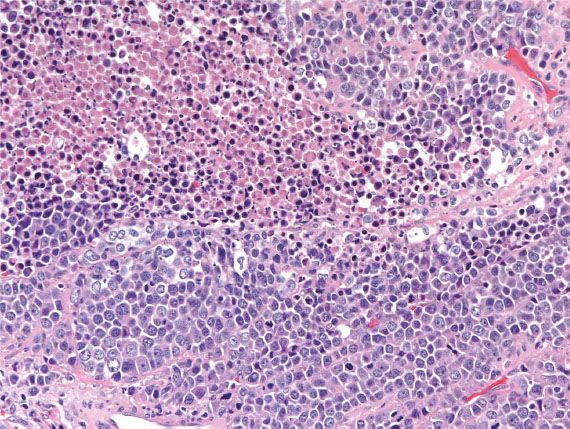

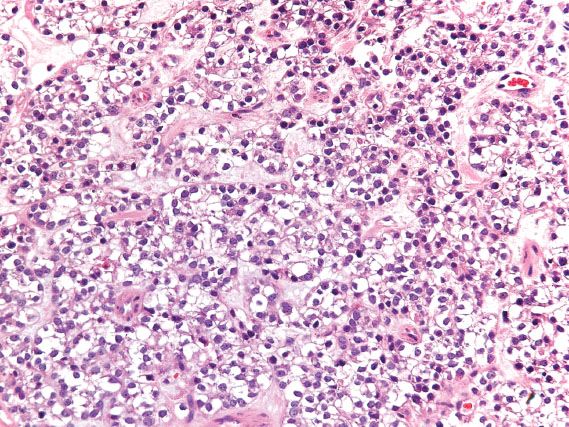

Neuroendocrine Carcinoma

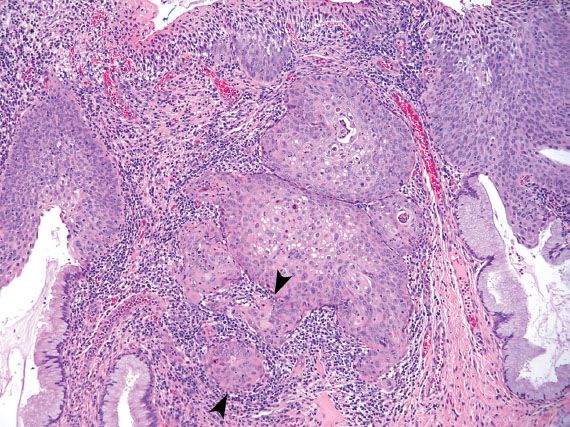

Neuroendocrine carcinoma, small- and large-cell variants, accounts for less than 5% of all cervical carcinomas. These highly aggressive tumors may present as small lesions, but most are deeply invasive. They exhibit the usual features of a neuroendocrine carcinoma; high mitotic indices and necrosis are common (Fig. 5.20). Neuroendocrine carcinoma is often associated with AIS, HSIL, and conventional invasive cervical adenocarcinoma. Most harbor HPV-18 and are p16-positive. Rarely, well-differentiated neuroendocrine tumors (carcinoid) may occur in the cervix and the prognosis for these tumors may be better. Metastasis should always be ruled out.

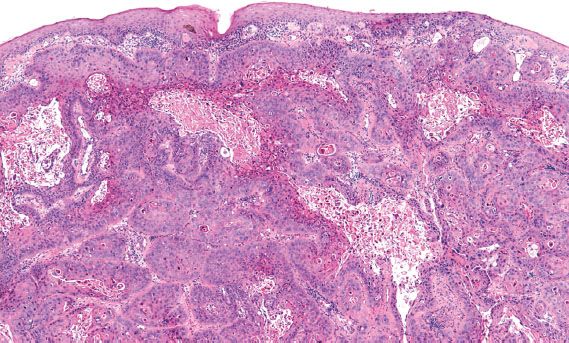

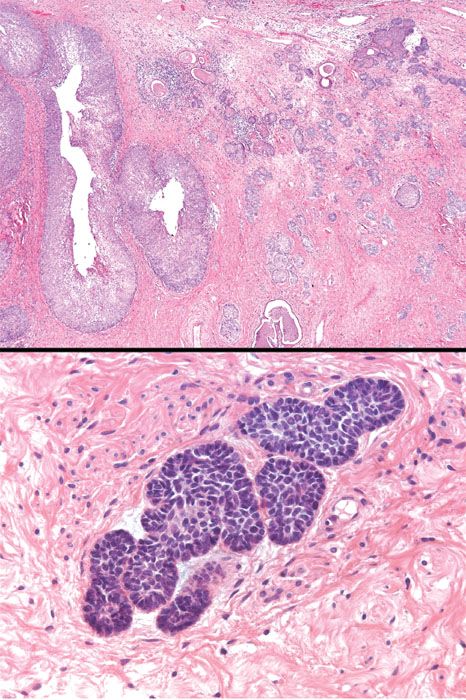

Adenoid Basal Carcinoma—Adenoid Basal Epithelioma

Adenoid basal cell carcinoma (epithelioma) occurs in postmenopausal, elderly women (mean age 65 years). Most are asymptomatic and the tumor is discovered during evaluation of an atypical Pap smear. Indeed, it is often associated with HSIL. The cervix is often normal on colposcopic and physical examination. The tumor is cytologically bland (often looking like “bland squamous cell carcinoma”), and features basaloid, adenoid, and squamoid differentiation. The adenoid areas consist of small, closely packed tubules, occasionally with intraluminal secretions reminiscent of mesonephric tubules (Fig. 5.21). There is typically no stromal response. Mitotic figures are rare or absent. The tumor has a favorable prognosis and needs to be distinguished from the adenoid cystic pattern of cervical adenocarcinoma, which does not have a favorable prognosis (21). Because of the extremely favorable prognosis associated with classic, superficial adenoid basal carcinoma, the diagnostic term adenoid basal epithelioma is preferred.

Figure 5.20 Neuroendocrine carcinoma of cervix. Malignant cells with high mitotic index are arranged in a sheetlike growth pattern. Necrosis is often present in these clinically aggressive tumors.

Figure 5.21 Adenoid basal carcinoma (epithelioma). This variant of cervical adenocarcinoma is characterized by nests of bland basaloid and squamoid cells in the cervical stroma. A squamous intraepithelial lesion is typically present in the overlying mucosa. This neoplasm is often referred to as adenoid basal epithelioma because it has a very favorable prognosis. (top, low power; bottom, high power)

Adenoid Cystic Carcinoma

Unlike adenoid basal carcinoma (epithelioma), adenoid cystic carcinoma is a clinically aggressive neoplasm. It is composed of cribriform nests containing eosinophilic hyaline material within the gland lumens, resembling adenoid cystic carcinoma of the salivary gland.

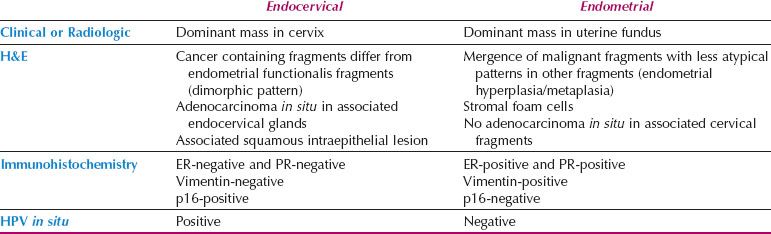

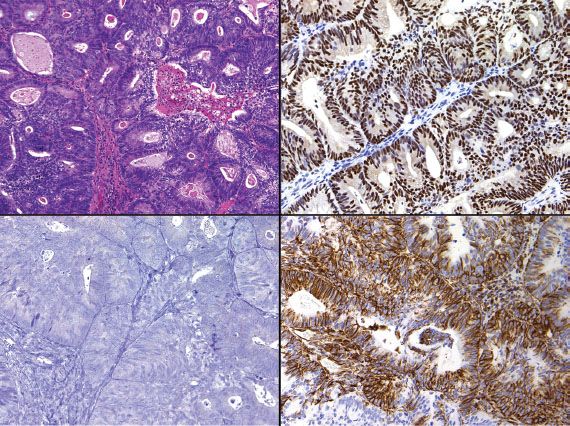

Table 5.4 Distinguishing Endometrial from Endocervical Adenocarcinoma

Localization of Adenocarcinoma: Cervix versus Corpus

Distinction between primary endometrial and primary endocervical adenocarcinoma may be difficult in biopsy and curettage specimens, especially when no precursor lesion is present. When clinical and histologic evaluation fails to clearly identify a carcinoma as cervical or endometrial in origin, an immunohistochemical panel that includes several markers, such as estrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PR), vimentin, and p16, is often useful (19,22,23). Using this particular panel (Table 5.4), glandular proliferations that are ER-positive and PR-positive, vimentin-positive, and p16-negative are almost always endometrial origin (Fig. 5.22), whereas those that are ER-negative and PR-negative, vimentin-negative, and p16-positive are very likely to be endocervical in origin (Fig. 5.23). Because the distinction between these two sites of origin may be based on whether a strong staining pattern with p16 is focal or diffuse in an individual case, this pattern of reactivity is most useful in whole tissue sections. In limited samplings, such as are encountered in routine biopsy and curettage specimens, these patterns may be misleading. In addition, overexpression of p16 can occur in a variety of other carcinomas independent of HPV status, including uterine serous carcinomas.

Figure 5.22 Endometrial adenocarcinoma (upper left). Endometrial adenocarcinoma is typically ER-positive/PR-positive (upper right), vimentin-positive (lower right), and p16-negative (lower left).

Figure 5.23 Endocervical adenocarcinoma (upper left). In contrast to endometrial adenocarcinoma (see Figure 5.22), endocervical adenocarcinoma is typically ER-negative/PR-negative (upper right), vimentin-negative (lower left), and p16-positive (lower right).

Mesenchymal Tumors

Stromal and smooth muscle tumors may occur in the cervix where they resemble their more common uterine counterparts. Although the vagina is the more common site, embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma may occur in the cervix; in contrast to vaginal rhabdomyosarcoma, which is more common in children, cervical rhabdomyosarcomas tend to occur in young adults. Most are embryonal, but alveolar variants may be seen.

Mixed Epithelial and Mesenchymal Tumors

The same mixed epithelial and mesenchymal tumors that occur in the uterine corpus may occur in the cervix. They tend to exhibit the same patient demographics as their uterine counterparts, but cervical adenosarcomas often occur at a younger age (24). Most present during the reproductive years with abnormal bleeding and recurrent polyps. Data are limited, but most appear to have a more favorable prognosis, possibly because of the early detection of low-stage disease in the majority of patients. As in uterine corpus tumors, deep invasion and sarcomatous overgrowth are adverse prognostic indicators.

Other Tumors

A variety of other neoplasms may arise in the uterine cervix. These include alveolar soft part sarcoma, rhabdomyoma, and nerve sheath tumors. Alveolar soft part sarcomas of the female genital tract appear to have a better prognosis than their counterparts in other sites. Yolk sac tumors may occur in the cervicovaginal region. Melanoma, lymphoma, and leukemia usually involve the cervix secondarily, either as metastases or in the setting of widespread disease (18).

Vagina

Squamous Lesions of the Vagina

Squamous Intraepithelial Lesion

The CAP-ASCCP LAST Project recommendations for standardized terminology apply across the anogenital tract for HPV-related preneoplastic squamous lesion. Consequently, preneoplastic lesions of the vagina are termed LSIL or HSIL with the corresponding vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia (VAIN) terminology in parentheses: LSIL (VAIN 1), HSIL (VAIN 2), HSIL (VAIN 3). LSIL and HSIL in the vagina have the same morphologic features as those in the cervix. LSIL can be mimicked by vaginal papillomatosis, which exhibits papillary architecture, parakeratosis, and cytoplasmic halos. However, papillomatosis lacks significant acanthosis and nuclear atypia. HSIL can be mimicked by atrophy and immature squamous metaplasia, but can be distinguished by a lack of nuclear atypia in the latter two entities.

Squamous Cell Carcinoma

Primary squamous cell carcinoma of the vagina is uncommon. Vaginal squamous cell carcinoma more frequently occurs as a result of secondary involvement by extension from the cervix or vulva. The morphologic features are the same as for the cervix. In patients with vaginal adenosis, immature squamous metaplasia involving areas of adenosis can be mistaken for invasive squamous cell carcinoma, but the two entities can be readily distinguished by the lack of cytologic atypia and the lack of desmoplastic response with the benign process.

Glandular Lesions of the Vagina

Clear cell adenocarcinoma is the most common malignant glandular lesion in the vagina, followed by endometrioid, mucinous, and mesonephric subtypes. The latter histologic subtypes occur predominantly in perimenopausal women.

Clear Cell Adenocarcinoma

Clear cell carcinoma of the cervicovaginal region is strongly linked to in utero exposure to diethylstilbestrol (DES) and has decreased in incidence with decreased use of this teratogen. It typically occurs in association with adenosis. Although the upper vagina is the most common site of involvement in DES-exposed women, the cervix is the most commonly affected site in non-DES–exposed women. The appearance is the same as the ovarian counterpart (Fig. 5.24), and prognosis is determined by tumor size, depth of invasion, and lymph node involvement.

Adenosis

The presence of ectopic glandular epithelium in the vagina is termed adenosis. Adenosis may exhibit mucinous endocervical-like epithelium or tuboendometrioid epithelium. It is often asymptomatic, but may be detected by colposcopic examination. Atypical adenosis, which exhibits architectural and cytologic atypia, is often seen in association with clear cell adenocarcinoma.

Fibroepithelial Stromal Polyp

Fibroepithelial stromal polyp is a common, typically small, exophytic polypoid lesion occurring in reproductive-aged women, most commonly in the vagina, but also in the vulva and cervix. Almost one-third occur during pregnancy. The polyps often occur in the anterior wall and range in size from 0.5 cm to 4 cm. Histologically, they are characterized by small spindle cells and enlarged, stellate, multinucleated cells in a myxoid stroma (Fig. 5.25). Mitotic figures can be prominent and may raise suspicion for a malignant process. Fibroepithelial stromal polyps are distinguished from sarcoma botryoides by the absence of a cambium layer.

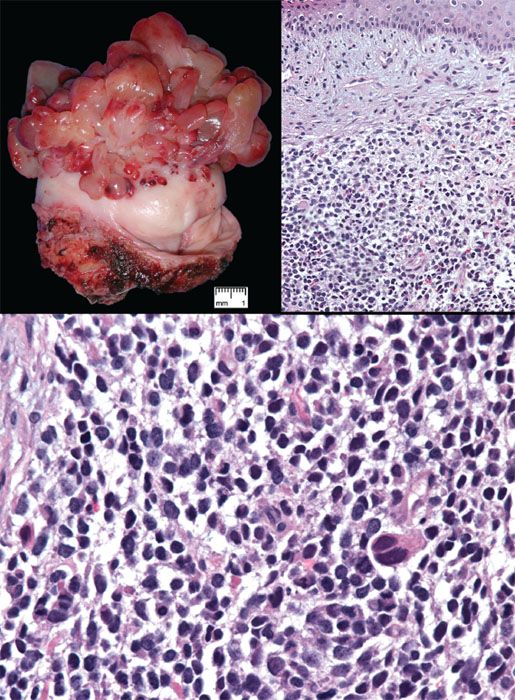

Sarcoma Botyroides

Embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma is the most common vaginal sarcoma; it occurs almost always in infants and children, but rare cases have been reported in young adults and postmenopausal women. The tumors present as polypoid vaginal masses, often protruding through the introitus, that may vary in size from 0.2 cm to 12 cm. Microscopically, the tumor is composed of small, round to oval or spindle-shaped cells surrounded by an edematous, myxoid stroma (Fig. 5.26). A characteristically dense, cellular cambium layer can be seen in the subepithelial zone. Rhabdomyoblasts (strap cells) are present but may be sparse or ill defined. Identification of rhabdomyoblasts can be facilitated by immunostaining for myogenin or Myo-D1.

Wide local excision and combination chemotherapy is the preferred treatment for sarcoma botyroides. Staging in children is based on the Intergroup Rhabdomyosarcoma Study Group classification; adults are staged according to the TNM and FIGO system. Most rhabdomyosarcomas in the vulvovaginal region are of the embryonal type, but rare tumors are of the alveolar type, which has a worse prognosis.

Figure 5.24 Clear cell adenocarcinoma of vagina. In this solid pattern of clear cell carcinoma, sheets of malignant cells with clear cytoplasm extensively replace normal tissue.

Melanoma

Melanoma is the second most common malignancy to occur in the vagina (after squamous cell carcinoma). Affected patients are typically 60 years of age and present with vaginal bleeding. Most, but not all lesions are pigmented, nodular, or flat, and measure 2 to 3 cm in size at diagnosis; ulceration may be present. The anterior wall of the lower third of the vagina is the most common site. The diagnosis may be difficult on small biopsies because an in situ component or pagetoid spread is often absent. Epithelioid cell lesions may resemble carcinoma, whereas spindle cell lesions may create confusion with sarcoma. Immunohistochemical stains for melanoma markers are often required to establish a diagnosis. The prognosis is poor.

Postoperative Spindle Cell Nodule

A variety of reactive processes may occur within the vagina, particularly following surgical procedures. One such lesion is composed of a cellular, spindle cell proliferation that may simulate a neoplastic process. This lesion has been designated as postoperative spindle cell nodule.

Vulva

Squamous Cell Lesions of the Vulva

Terminology

Similar to the cervix, there are multiple terminology systems in use to describe preneoplastic lesions of the vulva (25) (Table 5.5). The main difference lies in whether VIN is graded. The 2003 World Health Organization (WHO) classification grades VIN on a scale of 1 to 3, with VIN 3 further subdivided into classic type and simplex type. In contrast, the International Society for the Study of Vulvovaginal Disease (ISSVD) decided in 2004 to eliminate the category of VIN 1, and to abolish grading of VIN. This decision was based on the lack of evidence that condylomas, which account for the majority of VIN 1 lesions, progress to carcinoma, and the lack of interobserver reproducibility for diagnosing VIN 1 or for distinguishing between VIN 2 and VIN 3 (26). The ISSVD retained the distinction between classic VIN and simplex (differentiated) VIN. Given the variability in terminology, it is best to determine what terminology system the pathologist is using, especially if the diagnosis is “vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia (VIN)” with no further specification.

Figure 5.25 Fibroepithelial stromal polyp. Atypical stromal cells (inset) may simulate a malignancy, but this is a benign, probably reactive process. Although the lesion extends to the surface epithelium, there is no cellular condensation (forming a so-called cambium layer) at the surface; the absence of a cambium layer helps to distinguish this lesion from sarcoma botyroides on a limited sampling (see Figure 5.26). This polyp occurs most commonly in the vagina but can also be seen in the vulva and cervix.

Figure 5.26 Sarcoma botyroides (embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma). Top left: Botyroid growth pattern of cervical embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma (Courtesy of Dr. Matthew Quick). Top right: Stellate cells set in myxoid stroma are more condensed beneath the surface epithelium, forming a distinct cambium layer. Bottom: Small cells with hyperchromatic nuclei are punctuated by larger cells with more abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm.

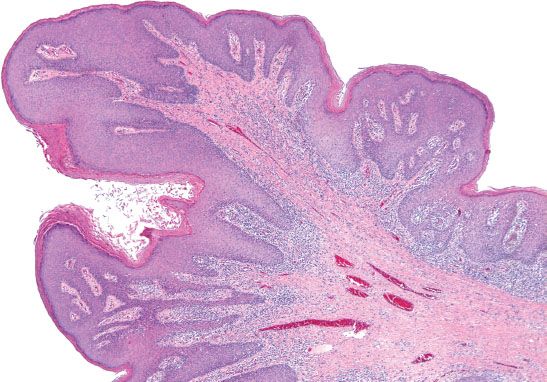

Vulvar Intraepithelial Neoplasia

In the vulva, there are two different pathways—HPV-related and HPV-unrelated—that lead to the development of squamous cell carcinoma. The two-tiered CAP-ASCCP LAST Project terminology applies to HPV-related precursor lesions of the vulva (1). LSIL consists predominantly of condyloma acuminata, which are associated with low-risk HPV types 6 and 11 (Fig. 5.27). Flat condylomas are uncommon in the vulva, but may be associated with high-risk HPV. Fibroepithelial polyps (skin tags) and hymenal mucosa can be mistaken for exophytic condylomas. Nonspecific inflammatory atypia or psoriasis can be misdiagnosed as flat condylomas.

Table 5.5 Terminology for Precursor Lesions of Vulvar Squamous Cell Carcinoma

Vulvar HSIL can be qualified as VIN 2 or VIN 3. High-risk HPV is identified in 53–90% of cases of HSIL (VIN 3), with HPV 16 the most common type (27). HPV 18, 31, 33, 35, 51, 52, and 68 have also been isolated from cases of vulvar HSIL (28).

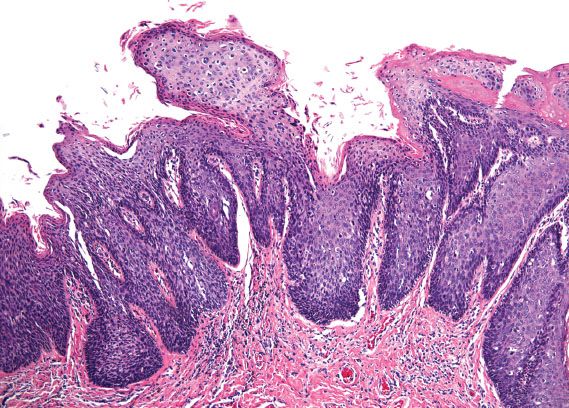

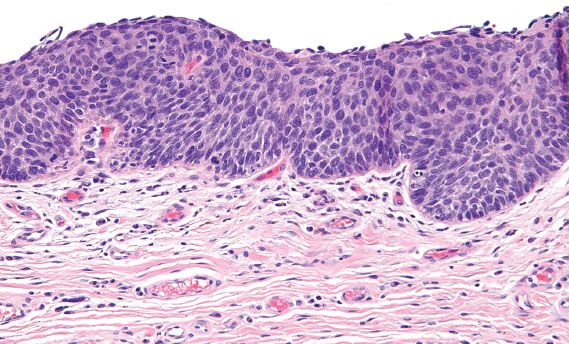

Vulvar HSIL is commonly multicentric, with extension to the perineum and involvement of the cervix and vagina. There are three patterns or subtypes of vulvar HSIL: warty, basaloid, and pagetoid. The warty pattern is characterized by prominent koilocytosis or warty architecture (Fig. 5.28), whereas the basaloid is more poorly differentiated (Fig. 5.29). The atypia involves two-thirds or more of the epithelium and is notable for disorganization, cells with high nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratios, dark irregular nuclei, and numerous mitotic figures, including abnormal forms. Dyskeratotic cells are often present, and the dysplastic cells frequently extend down pilosebaceous units, which can mimic invasive carcinoma.

Figure 5.27 Condyloma. Exophytic condylomas are common in the vulva and are associated with low-risk HPV types 6 and 11.

Figure 5.28 Classic VIN, warty. Prominent koilocytosis is present on the surface and overlies severe atypia involving two-thirds of the underlying epithelium.

Figure 5.29 Classic VIN, basaloid. Cells with high nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratios and dark, irregular nuclei involve the full thickness of the squamous epithelium.

The pagetoid subtype is rare but important to recognize because it can closely mimic extramammary Paget disease. The distinction between these two entities requires special stains, because histologically, they both are characterized by single cells and clusters of cells with pale cytoplasm involving the squamous epithelium of the vulva.

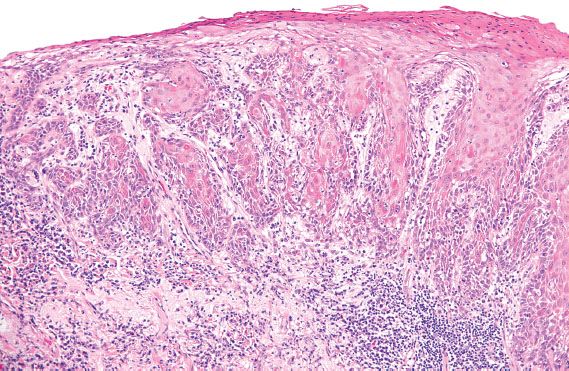

Figure 5.30 Simplex VIN. Abnormal keratinocytes with abundant, markedly eosinophilic cytoplasm involve the mid to superficial layers and extend into the elongated, branching rete ridges.

Differentiated or simplex VIN is localized to the vulva and usually identified adjacent to areas of invasive carcinoma in elderly patients. It is rarely identified prospectively (29). In contrast to vulvar HSIL, HPV is rarely identified in simplex VIN (28). The morphologic changes of simplex VIN are subtle, and characterized by nuclear atypia of the basal cell layer and expansion of the basal layer into elongated, narrow, branching rete ridges (Fig. 5.30). The nuclei can range from relatively small, dark and irregular, to enlarged and pleomorphic. Maturation is abnormal, as exhibited by the presence of enlarged keratinocytes with large, pleomorphic nuclei and abundant, markedly eosinophilic cytoplasm in the mid- to superficial layers. These abnormal keratinocytes can extend into the basal layer and involve the rete ridges (29). The thickness of the epithelium is variable, and can be atrophic or acanthotic (i.e., thickened). The differential diagnosis for simplex VIN includes lichen sclerosus with squamous hyperplasia, and other benign dermatologic conditions such as lichen simplex chronicus, psoriasis, spongiotic dermatitis, and candida vulvitis.

Lichen sclerosus is a potential risk factor for the development of vulvar squamous cell carcinoma. It may play a role in the HPV-independent pathway. Lichen sclerosus is negative for HPV and is more frequently identified in association with simplex VIN than with classic VIN (27,28).

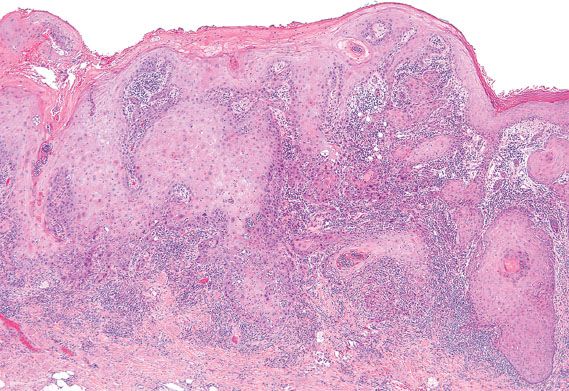

Squamous Cell Carcinoma

Primary invasive squamous cell carcinomas of the vulva can be subdivided into two main types: conventional squamous cell carcinoma and verrucous carcinoma. Conventional squamous cell carcinomas can exhibit different growth patterns, including warty, basaloid, and keratinizing (Fig. 5.31). Invasive squamous cell carcinomas that have warty or basaloid features are typically associated with classic VIN and high-risk HPV, whereas well-differentiated keratinizing squamous cell carcinomas are more commonly associated with simplex VIN (27).

Verrucous carcinoma is a rare special variant of squamous cell carcinoma that is slow growing and has minimal metastatic potential. It is typically exophytic, well circumscribed, and composed of hyperkeratotic fronds of cytologically bland squamous epithelium. The interface with the underlying stroma characteristically consists of a pushing border with associated chronic inflammation (Fig. 5.32).

Figure 5.31 Conventional keratinizing squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva. Nests of well-differentiated tumor cells jaggedly invade into the stroma on microscopic examination.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree