PATHOGENESIS OF HYPOPITUITARISM

Part of “CHAPTER 17 – HYPOPITUITARISM“

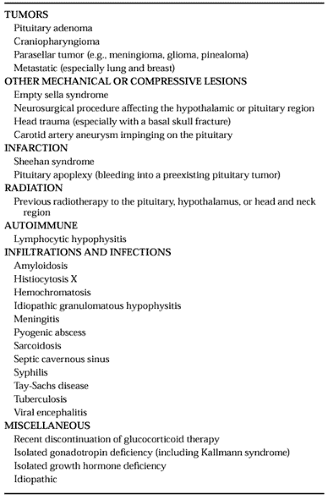

Table 17-1 lists many of the causes of hypopituitarism. There are no reliable statistics for the percentage of patients in each subgroup, but pituitary tumors represent the largest single category, and a pituitary adenoma (see Chap. 11) is the most common single cause of hypopituitarism in adults.

TUMORS

Pituitary adenomas originate within the sella from one of the cell types found in the anterior pituitary. They may be secretory, with a resultant increase in the serum concentration of one of the pituitary hormones and evidence of, for example, Cushing syndrome or acromegaly. Alternatively, the adenoma may be clinically nonfunctioning, without evidence of hormonal hypersecretion; however, some clinically nonfunctioning tumors secrete hormonal precursors with diminished or absent biologic activity.4 Even when an adenoma is hypersecretory, concomitant evidence of hypopituitarism is common because of the tumor effects on adjacent nontumorous pituitary tissue. Patients with microadenomas

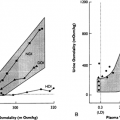

(<10 mm)may or may not have hormone deficiencies; they most commonly have diminished gonadotropin secretion.5,6 At least 30% of patients with macroadenomas (>10 mm) have a deficiency of one or more pituitary hormones, most commonly GH.1

(<10 mm)may or may not have hormone deficiencies; they most commonly have diminished gonadotropin secretion.5,6 At least 30% of patients with macroadenomas (>10 mm) have a deficiency of one or more pituitary hormones, most commonly GH.1

Craniopharyngiomas (see Chap. 11) may be sellar—or more often, suprasellar—and frequently contain calcifications. These tumors are congenital and may cause growth retardation, diabetes insipidus (DI), or mass-related symptoms. They commonly cause hypopituitarism in children, but symptoms may not appear until adulthood.7

Other tumors can occur in the pituitary or hypothalamic area and cause compression and hypopituitarism. Among the many possibilities are meningiomas, gliomas, and metastases, especially from breast and lung cancer. Pinealomas (see Chap. 10) are worthy of special mention because they often respond well to radiotherapy. If the computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan shows a tumor in the pineal area, the serum and cerebrospinal fluid should be tested for α-fetoprotein and β-human chorionic gonadotropin, and the cerebrospinal fluid cytology should be checked. In the past, when biopsy of the pineal area was associated with a much greater risk, treatment was customarily initiated based on the previously described tests alone if the results were compatible with the diagnosis of pinealoma. However, these results were sometimes misleading. Biopsies in the pineal area can be done more safely now, and some physicians recommend that the diagnosis be confirmed by biopsy before treatment is initiated.8

The mechanisms by which pituitary tumors cause hypopituitarism include mechanical compression of normal pituitary tissue and interference with delivery of hypothalamic hormones to the pituitary via the hypothalamic-hypophysial portal system. In addition, supraphysiologic prolactin levels may diminish hypothalamic gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) secretion, resulting in decreased gonadotropin secretion and hypogonadism. A patient with a pituitary tumor of any size may have a deficiency of one or any combination of hormones. Therefore, upon diagnosis of a pituitary tumor, before therapy, the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis and hypothalamic–pituitary–thyroid (HPT) axis should be evaluated, and prolactin should be measured. Evaluation of other axes may be undertaken, depending on individual circumstances. Hypopituitarism caused by a pituitary tumor may be reversible; surgical removal of the tumor or shrinkage via medical therapy is often accompanied by return of normal pituitary function. However, treatment of pituitary tumors with surgery or radiotherapy may worsen or cause hypopituitarism.

OTHER MECHANICAL OR COMPRESSIVE LESIONS

The discovery of an enlarged sella turcica on a skull radiographic film suggests a pituitary tumor. However, the empty sella syndrome (see Chap. 11 and Chap. 20) is another common cause of an enlarged sella.9 The sella may be enlarged and the pituitary gland compressed by pressure from meningeal tissue that has herniated into the sella. Although the pituitary is atrophic and the sella cavity appears empty on radiologic studies, because there is sufficient residual functioning pituitary tissue, the patient is typically endocrinologically normal; nevertheless, hormonal deficiencies occasionally occur. A CT or MRI scan of the head can usually differentiate a pituitary tumor from the empty sella syndrome. Usually no pituitary tumor is present, but there occasionally may be a microadenoma in the residual pituitary tissue.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree