Breast conservation therapy (BCT) is a popular treatment option for women with breast cancer, and that trend continues to rise.1 This is in part driven by equivalent survival rates and by preservation of body image, quality of life, and reduced psychological morbidity with breast-sparing surgery.2,3 However, there remains an innate conflict between the goals of oncology and cosmesis, with the former being to eliminate all locoregional disease, and the latter relying on preservation of as much breast tissue as possible for optimal aesthetic outcome. The wider the margin of resection, the lower the risk of local recurrence,4,5 and it often becomes a dilemma for the surgeon to meet both these end points. Breast shape becomes compromised and significant contour deformities, breast asymmetry, and poor aesthetic outcomes are not uncommon. Up to 30% of women will have a residual deformity that may require surgical correction,6 the correction of which is often difficult.7

In order to support the complex nature of the ever-expanding criteria for breast conservation, there has been a surge of reconstructive techniques for the partial mastectomy defect prior to breast irradiation, often referred to as the oncoplastic approach. This approach is intended to improve outcomes from both an oncologic as well as a cosmetic standpoint by combining the principles of oncology and plastic surgery.

The 2 main options available include (1) volume displacement techniques using parenchymal remodeling (volume shrinkage) and (2) volume replacement techniques using local or distant tissue (volume preserving). The decision is usually based on tumor characteristics (size and location), breast characteristics (size and shape), and patient desires. Large- or moderate-sized breasts, or ptotic breasts with sufficient parenchyma remaining following resection are amenable to reshaping procedures. When additional tissue (volume and skin) is required to maintain the desired breast size or shape (ie, smaller or nonptotic breasts), volume replacement procedures are required. The focus of this chapter is volume displacement (parenchymal modeling) techniques using local breast tissue.

Breast reshaping procedures all essentially rely on advancement, rotation, or transposition of a large area of breast to fill a small- or moderate-sized defect. This absorbs the volume loss over a larger area. In its simplest form, it entails mobilizing the breast plate from the area immediately around the defect in a breast flap advancement technique as proposed by Anderson et al.8

Other local breast options include dermatoglandular flaps to fill small defects that might otherwise have caused an unfavorable result due to skin or parenchymal deficiency being inadequately reconstructed.

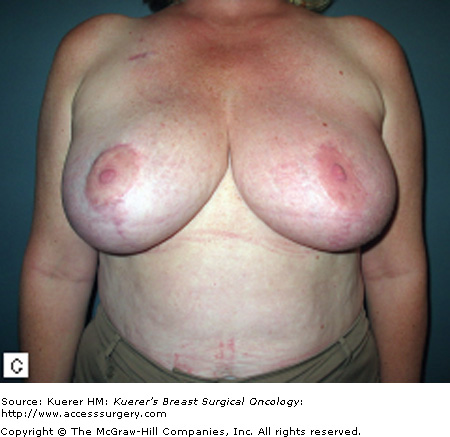

The use of reduction or mastopexy techniques to reconstruct the partial mastectomy defect prior to breast irradiation has recently become more popular, and will be discussed in detail below. This approach initially became popular in Europe for reconstructing quadrantectomy defects in the lower pole.9 In the United States, the popularity likely evolved out of frustration in the management of breast cancer patients with macromastia.10-13 Plastic surgeons are all familiar with these techniques, making the incorporation of this approach into their reconstructive practice an easy addition. Women with large pendulous breasts are often more difficult to reconstruct following total mastectomy due to body habitus and the inherent difficulty associated with skin envelope reduction and other morbidities. They are often deemed poor candidates for reconstruction and associated with increased complications and unfavorable cosmetic results (Fig. 76-1).

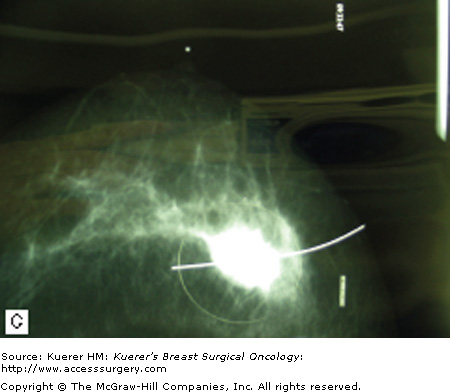

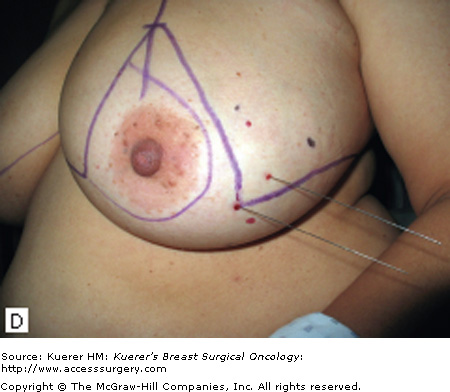

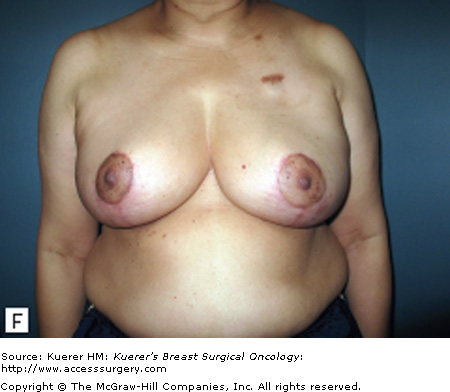

Figure 76-1

A 46-year-old female with bilateral macromastia (bra size 36G) with left-sided invasive ductal carcinoma. She expressed an interest in breast preservation and it was felt that given her large breasts she would be a better candidate with a simultaneous breast reduction. Skin-sparing mastectomy and reconstruction would be difficult given her breast size and body habitus. She had a left partial mastectomy (225 g) from the lateral quadrant with clear margins. A simultaneous superomedial breast reduction was performed removing an additional 1050 g from the left breast and 1205 g from the right side. She is shown 6 months following radiation therapy with preservation of shape and symmetry.

Macromastia was initially felt to be a relative contraindication to BCT with poor cosmetic results, greater radiation fibrosis, and less effective radiation therapy.14-17 On the other hand, women with macromastia and large pendulous breasts are often overweight, and total breast reconstruction is more challenging, being associated with higher complication rates and less favorable cosmetic outcomes. The addition of reduction mammaplasty techniques was therefore welcomed by the patient, the resective surgeon, and the reconstructive surgeon. It allows women with macromastia to be candidates for breast conservation without having to accept significant deformities; it allows the resective surgeon to remove a generous amount without having to worry about a residual deformity; and it makes breast reconstruction more predictable in an otherwise difficult patient population.

The indications for partial breast reconstruction using local tissue are numerous. The 2 main reasons to reconstruct partial mastectomy defects are (1) to increase the indications for BCT, making breast conservation practical in patients who otherwise might require a mastectomy, and (2) to minimize the potential for a poor aesthetic result.

Women with large pendulous breasts who are felt by the surgeon to be poor candidates for BCT alone benefit from the oncoplastic reduction techniques, minimizing the potential for a poor cosmetic result and allowing them to be candidates for breast conservation. The ideal patient is one whose tumor can be widely excised within the reduction specimen, and for whom a smaller breast is viewed as a positive outcome. Older women with macromastia are well suited for this approach compared to mastectomy and reconstruction. Another indication for the oncoplastic reduction technique is when the surgeon anticipates a large defect, or is concerned about being able to achieve clear margins in women with moderate to large breasts (Fig. 76-2). The potential for an unfavorable result exists in this situation regardless of breast size or tumor location. Other indications are patient driven, in those women who desire breast conservation, or who desire smaller breasts due to their limitations caused by symptomatic macromastia. As we become more comfortable with these techniques the indications will become more liberal. Essentially anyone with large breasts amenable to breast conservation is a candidate for this procedure. However, the importance of stringent patient selection criteria cannot be overstated, and is required to ensure maximal cosmetic outcomes as well as oncological safety.

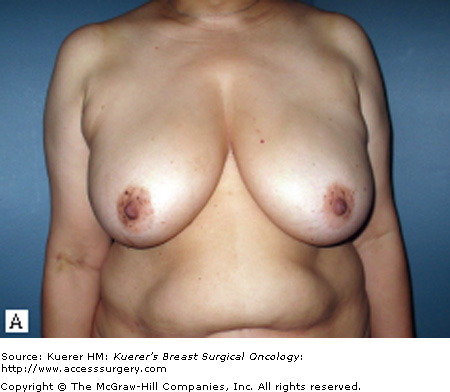

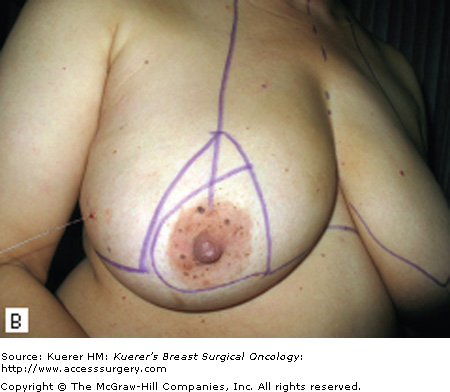

Figure 76-2

This 53-year-old female had a history of right-sided breast cancer and some suspicious areas on the left breast. She underwent a right lateral partial mastectomy (200 g) and an additional 80 g with her simultaneous superomedial breast reduction. On the left side her biopsy was negative for carcinoma with the specimen weight 90 g, and an additional 250 g from that side.

Partial mastectomy defects in the central or lateral location, or high tumor to breast ratios (more than 20%) will often benefit from reconstruction. Mastopexy techniques that reposition the nipple will often allow preservation of shape and symmetry in ptotic or even asymmetric breasts when used in combination with lumpectomy.

Contraindications include patients who are not good candidates for breast conservation, a history of prior irradiation, or situations when there is insufficient residual breast tissue following resection to allow reshaping. Similar selection criteria are used when deciding on elective breast reduction procedures and need to be taken into consideration. Patients with multiple medical comorbidities or active smokers are not ideal candidates for additional elective surgery, and the risks will often outweigh the benefits in these situations.

The general trend is to reconstruct the partial mastectomy defect prior to breast irradiation with the benefits of not operating on an irradiated, scarred, and contracted breast where the lack of elasticity makes reconstruction more difficult. Reconstruction prior to radiation therapy is considered immediate reconstruction. There are situations where poor results are encountered years following radiation therapy, which then require delayed reconstruction. Similar techniques are employed in delayed reconstruction, more often requiring flaps such as the latissimus dorsi myocutaneous flap, and are associated with higher complication rates (42% vs 26%) and worse cosmetic outcome.7 The main concern with immediate reconstruction is the potential for positive margins. Delayed-immediate reconstruction is another alternative where the reconstruction is delayed a week until final margin status has been determined. This gives the benefit of immediate reconstruction with the luxury of negative margins, however, at the expense of a second procedure.

One of the most important variables in ensuring a safe oncologic outcome is patient selection and how it relates to margin status. Positive margins on final are potentially complicated by altered architecture if parenchymal rearrangement has already been performed. The options for managing positive margins include reexcision or completion mastectomy and reconstruction. The extent of the disease in these situations, especially given the previous generous oncoplastic resection, will often dictate that completion mastectomy is a more appropriate treatment plan. If reexcision is performed, this needs to be done with the reconstructive surgeon. Fortunately the incidence of positive margins using this approach is felt to be less given the more generous resections. We have demonstrated specimen weight over 200 g in oncoplastic resections, compared to about 50 g for nononcoplastic procedures (Fig. 76-1).10,18 The incidence of positive margins is less in oncoplastic resections.19 When completion mastectomy and reconstruction is required, the disadvantages of the reduction procedure are minimal. The benefits of this approach are that (1) no reconstruction options (ie, flaps) have been used; (2) the contralateral symmetry procedure has already been performed; (3) skin envelope has been reduced; and (4) it is now easier to reconstruct a smaller reduced breast than a large ptotic one.

One way to avoid positive margins is to delay reconstruction a few weeks until confirmation of margin status has been obtained (delayed-immediate reconstruction). Most series report a positive margin rate of about 5% to 10%, and rather than perform an unnecessary second procedure 90% to 95% of the time, we need to minimize the incidence of positive margins. Preoperative breast imaging (ie, magnetic resonance imaging [MRI], ultrasound, or mammography) is helpful in determining the extent of the disease guiding the necessary resection and should be employed judiciously when indicated. An imaging study showed that tumor size was underestimated 14% by mammography and 18% by ultrasound, whereas MRI showed no difference when compared to the pathological specimen.20Separate cavity margins sent at the time of lumpectomy significantly reduce the need for reexcision. Cao et al demonstrated that final margin status was negative in 60% of patients with positive margins on initial resection.21 Additional intraoperative confirmatory procedures include radiography of the specimen and intraoperative frozen sections for invasive cancer. Patient selection is another important consideration. A recent series has demonstrated a higher rate of positive margins in women under the age of 40 years old with extensive ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS), suggesting delayed immediate reconstruction in those situations.10 Other patients with potentially difficult margin issues include those with prior chemotherapy, infiltrating lobular carcinoma, and multicentric disease. In these patients, and in any other patient where there is intraoperative concern regarding margin status, the reconstruction should be delayed until margin status has been confirmed.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree