Parasites

Mervat Z. El Azzouni, MD, PhD  Radwa G. Diab, MD, MBBCH, PhD

Radwa G. Diab, MD, MBBCH, PhD

Overview

Many parasites were studied for a possible role in oncogenesis. Schistosoma haematobium was proved to play an important role in developing urinary bladder cancer. Other Schistosoma species, Schistosoma japonicum is classified as a colorectal carcinogen especially in the Far East. Other helminths Clonorchis and Opisthorchis are proved to induce hepatobiliary cancer. In Africa, a strong correlation between Ebstein–Barr virus infection and Burkitt lymphoma is present, with an evident enhancing role for Plasmodium falciparum. Chronic inflammation was incriminated to be the most accepted mechanism for parasite-induced cancer; however, the roles of certain carcinogens, oncogenes, DNA mutations, and others were all approved as mechanisms enhancing carcinogenesis in parasitic infections. Strikingly, despite the above-mentioned data, it seemed that certain parasites can modulate the host immune response in a manner that could lead to cancer regression or prevention. This is in the prospect of revaluation of the clinical importance of infectious agents; an issue that requires future concern.

The intensity of parasitic infection frequently correlates with its prevalence.1 Thus, when relatively uncommon neoplasms are noted with undue frequency in countries with a high prevalence of parasitic diseases, the question of the role of parasites arises. In this respect, the two most intriguing examples are probably the relationships of schistosomiasis to bladder cancer (BC) and that of malaria to Burkitt lymphoma (BL). Classic references have been presented before.2

Schistosomiasis and cancer of the bladder

Schistosoma haematobium was first incriminated for a potential role in induction of urinary BC in Egypt in 1911 by Fergusson3; an issue that was finally confirmed by the International Agency of Research on Cancer (IARC) in 1994; which reported the parasite as a carcinogen.4 Bilharzial bladder cancer (BBC) is theoretically a preventable malignancy if nationwide preventive strategies, including snail control and mass treatment campaigns, and screening projects could be adopted.5

Epidemiologic aspects

The highest incidence rates of BC are found in the countries of Europe, North America, and Northern Africa.6 Smoking and occupational exposure are the major risk factors in Western countries; however, the morbidity and mortality due to BC have declined over the past decade owing to changing the habits of cigarette smoking.7 Chronic infection with S. haematobium in developing countries, particularly Africa and the Middle East, accounts for about 50% of the total burden,8 with Egyptian males having the highest mortality rates (16.3/100,000).9 The association between S. haematobium infection and BC is far greater than that for any other parasitic infection,10 and it was classified as group 1 carcinogen.11 Association between S. haematobium and BC was initially established through case-controlled studies and close correlation of the incidence of BC with the prevalence of parasite. Clinically, the evidence of association was based on the presence of parasite eggs and Schistosoma-induced histopathological changes in cases of BC.12

Urinary BC is morphologically heterogeneous. More than 90% of the cancers are of the transitional cell carcinoma type (TCC),13 as in case of BC associated with smoking and occupational hazards.14 In Africa, squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) of the bladder is greatly overrepresented among the fellaheen of Egypt and the Africans of Mozambique, Zimbabwe, and Zambia (formerly Rhodesia), where S. haematobium is endemic.15–17 However, a shift toward TCC subtype was observed in developing countries owing to shift in risk factors with increased urbanization and industrialization.7 In Egypt, following the construction of the High Dam in the 1960s that led to changes in the water flow with direct impact on the intermediate snail host, S. haematobium was gradually replaced by Schistosma mansoni that causes intestinal rather than urinary disease.18 Furthermore, effective oral treatment campaigns in Egypt since 1977 resulted in significant decrease in urinary schistosomiasis.19 Strikingly, despite the large decline in S. haematobium infection in Egypt, BC continues to be the most common cancer among males. This is because the decline in BBC is being offset by increase in smoking-associated BC.20 This is evidenced by the shift in the incidence of SCC in Egypt from 78% in the 1980s to 27% in 2005 with a shift to TCC.21 Another retrospective study was conducted in Egypt, from 2001 to 2010, on two groups: group 1 included 1002 patients from 2001 to 2005 and group 2 included 930 patients from 2006 to 2010. The authors found that the incidence of BBC decreased from 80% in group 1 to 50% in group 2. Besides, a significant increase in TCC from 20% to 66% was observed with a significant decrease in SCC from 73% to 25% by comparing the two groups.22 Hamed et al.23 suggested another cause for the general decline in BBC in Egyptian governorates. Tendency toward warming, with high temperature exceeding 45°C, and increased number of hot days all over the year are incriminated in damaging the effectiveness of the snail host and hence schistosomal transmission.

The association of BC with schistosomal infection seems to become stronger with long standing and more severe infection.24 In Egypt, this association is directly related to the extent of perennial irrigation through canals, which creates a constant risk of reinfection, and inversely related to control measures and availability of safe and effective therapy.25 Children of school age are especially at risk because of their daily contact with infected water in rural areas.26 Besides, it was noted that in endemic areas in Iraq, Coastal Kenya, Ghana, Malawi, Mozmbique, Zambia, and Zimbabwe, a high association between S. haematobium and BC is present, whereas it was absent in Nigeria and areas in Southern Africa and Saudi Arabia with moderate to high prevalence of S. haematobium.27 Typically, schistosomiasis is a disease affecting agricultural communities, particularly those dependent upon irrigation to support their agriculture. The problem became much more significant in the nineteenth century, when the combination of new irrigation projects and population increases led to a higher probability of exposure to the parasite.28

Geographical distribution of S. haematobium seems to play an important role in determining the susceptible groups as regards their age and gender. The peak incidence of BC in schistosomiasis-nonendemic areas is in the sixth and seventh decades of life.29 In Egypt, Sudan, Iraq, Zambia, Malawi, and Zimbabwe, the mean age of the highest incidence of BC is between 40 and 49 years.10 The male : female ratio of BBC incidence in Schistosoma-endemic countries is in average 5 : 1,30 and this could be explained by prolonged contact with infected waters during agricultural activities in rural areas, which are normally done by men rather than women.5 Recent observation showed that the relative frequency of BBC was increasing among females during the period 1995–2005 in Egypt. This was explained by increasing migration of male farmers from the Nile Valley and Delta to the Urban and Frontier governorates seeking for jobs. Therefore, the females were expected to take place of their husbands in agricultural work and thus their exposure risk to infection was increased.23 Another study found that females were more affected by BBC (51.4%) compared to the males in the western part of Tanzania on the shores of Lake Victoria in the period 2000–2010.31

Variability in criteria for diagnosing urinary schistosomiasis influences the epidemiological rates for BBC. Ruling out a diagnosis of schistosomiasis because of the absence of ova in the centrifuged urine specimen would be unrealistic in many cases of contracted bladder owing to bilharzial fibrosis, in which the dense scar tissue precludes shedding of ova from the submucosa.25 Thus, by expanding the criteria for diagnosis of bilharzial bladder to include recent imaging and molecular techniques with high sensitivity and specificity, the epidemiological rates for BBC are expected to be more accurate.

Progression of bilharzial bladder cancer

BC cells require the acquisition of certain properties before being able to grow rapidly, invade, and metastasize.5

Chronic infection leads to trapping of Schistosoma eggs in the bladder wall. Proliferation of cells in the bladder mucosa results from constant irritation and inflammation.12 This mucosal damage increases the frequency of urinary tract infection.32 Besides, activated macrophages induced at the sites of inflammation are implicated in the generation of carcinogenic N-nitrosamines and reactive oxygen radicals.33 Mucosal fibrosis and dysuria associating chronic inflammation and bacterial infection lead to urinary stasis that, in turn, allows prolonged contact of urothelium with these carcinogens.34

Nitrate-reducing bacterial species accompanying urinary schistosmiasis can mediate the N-nitrosation of amines10 with the liberation of N-nitroso compounds.35 At the molecular level, these compounds are implicated in tumorigenic alkylation of specific bases and DNA sequences,36–38 leading to mutations in oncogenes, tumor suppressor genes, and genes for cell cycle control.5 Molecular events associating BBC include the activation of H-ras gene,39 inactivation of p53,40 and inactivation of retinoblastoma (Rb) gene.41 In 2010, Botelho et al.42 suggested that the parasite extract had carcinogenic ability through oncogenic mutation of the K-ras gene. The frequency of p53 mutations varies with the different grades of BBC.43 For BBC in Egypt,44 it was reported that about 86% had p53 mutations in exons 5, 6, 8, and 10 and that the in activation of p53 ranged from 0% to 38% at the early stage of the disease, as opposed to 33–86% in the advanced tumor stage.43 On the other hand, habitual smoking in a group of Japanese BC patients did not increase the frequency of p53 mutations, but caused unusual AT : GC mutation patterns.44 Mutations observed in p53 gene mostly involve transitions at CpG dinucleotides, which are in excess in cases of BBC. These transitions are explained by the effect of nitric oxide produced by the inflammatory response to Schistosoma eggs. Nitric oxide, released during the inflammatory response, can cause such mutations directly by deamination of 5-methylcytosine or indirectly via its capacity to form endogenous N-nitroso compounds leading to DNA alkylation.45 Over representation of the protein encoded by the MDM2 gene found in the majority of the studied cases may account for the frequent inactivation of the p53 gene observed in BBC, and hence the accumulation of DNA damage and the aggressive clinical course.46

Cancer development is closely related to uncontrolled cell cycles.47 Deletions and mutations in the gene coding for p16INK4, a cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) inhibitor, were found in 53% of BBC.48 Moreover, deletions in chromosome 9, where the CDKN2 gene is located, were found in 92% of SCC in Egypt.49

Human papilloma virus

The possibility of association between HPV and BBC remained open for long.50 A study done by Khaled et al.51 showed that the virus was present in 23 out of 40 cases of BBC. Recently, a study using the Mass ARRAY technology showed all BBC blood-tested samples to be associated with HPV-16 DNA.52

Metabolic observations during schistosomiasis

In the study of BBC, the metabolism of tryptophan along the formylkynurenine pathway leading to nicotinic acid has elicited considerable interest.53 The justification for this interest originally stemmed from industrial oncology; however, epidemiologic support is also derived from the high prevalence of classic pellagra that used to be observed in Egypt but not in other parts of Africa where SCC is infrequently reported despite endemic schistosomiasis. In pellagra, exaggeration of the pathway from tryptophan to nicotinic acid occurs, producing larger amounts of tryptophan intermediates along the formylkynurenine pathway.25

Our understanding of the role played by Schistosoma infection in disturbed tryptophan metabolism is complicated by geographic variations of dietary habits. In fact, serotonin metabolites such as 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid, which are excreted in large amounts by plantain-eating Africans, are low in Africans on other diets.54 Similar differences attributable to dietary habits have been found between bilharzial patients in Mozambique and South Africa. Egyptian peasants are not plantain eaters but subsist mostly on beans, lentils, and rice. Those with bilharzial cancer metabolize tryptophan into 3-hydroxyanthranilic acid, anthranilic acid, 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid, and kynurenine. The excretion of these metabolites is enhanced by a loading dose of tryptophan. Therefore, schistosomiasis should not be considered the only causal factor in the associated excretion of abnormal tryptophan metabolites because, with or without cancer, urinary schistosomiasis is almost universally accompanied by urinary tract infection. The bacterial flora may, thus, contribute to a spurious accumulation of some metabolites of tryptophan.25

Potentially carcinogenic metabolites of tryptophan, which may be the true oncogenic agent in the presence of bilharzial bladder inflammation, are principally determined by hepatic metabolic patterns. Factors that bear on this are coincident infestation of the liver by S. mansoni, pyridoxine deficiency, and chronic protein starvation. In the presence of advanced abnormalities in any of these factors, certain amounts of potential carcinogenic metabolites might be formed owing to lack of hepatic enzymes or cofactors.55, 56 The hepatic drug-metabolizing capacity of mice infected with S. mansoni is markedly reduced.57 The mutagen-inactivating potential of S. japonicum-infected mouse liver is similarly reduced,58 which results in longer persistence of the mutagen in the host body.59 It seems likely that the carcinogen dose is a determining factor in the aggressiveness of a bladder tumor, and that a low-grade carcinoma can be converted into a high-grade one if exposed continuously to low doses of N-nitroso compounds. This would explain, at least in part, the overrepresentation of deeply invasive SCC in the bilharzial urinary bladder.60

Apoptosis in schistosomal bladder cancer

One negative impact of the several cytogenetic changes that happen in the course of chronic schistosomiais is decreasing cell apoptosis and thus enhanced oncogenesis.12 In 2009, Botelho et al.61 showed that cells exposed to S. haematobium total antigen (worm extract) were found to divide faster than those not exposed to the antigen, and died much less. This was explained by increased level of Bcl-2, which is one gene that can contribute to oncogenesis by suppressing apoptosis.5 The overexpression of the Bcl-2 gene in BBC patients was found to be upregulated in SCC but not TCC.62

Pathology of benign and preneoplastic schistosomal bladder lesions

An intense, delayed-sensitivity reaction is elicited by viable Schistosoma eggs plugging the vesical venules leading to tubercules, nodules, or polyps. In bilharzial cystitis, the papilloma, covered as it is by one or two layers of flattened cells, which merge with the transitional epithelium at its base, is essentially a granuloma and not a precancerous lesion. With recurrent inflammation and fibrosis, some transitional epithelial cells become sequestered in the vesical submucosa and acquire a globular arrangement around a central cavity. When they open into the bladder cavity, the cystic formations become pseudoglandular. These structures, as part of cystitis glandularis, are at times precancerous; an adenocarcinoma may arise from the columnar epithelium, into which their lining has differentiated. In patients with schistosomiasis, squamous metaplasia is frequently encountered because it is a common concomitant of chronic inflammation. This type of metaplasia is a nearly consistent precursor of BC, and for this reason, leukoplakia acquires clinical importance as a precancerous condition.25

Site of origin

In patients in Western countries, BC frequently arises in the trigone; in patients in Egypt, it usually develops in areas remote from the ureters, mostly in the anterior and posterior bladder walls. This peculiarity tends to strengthen its association with schistosomal infection because the scanty or altogether absent submucosal tissue of the trigone discourages significant deposition of ova.25

Histologic classification

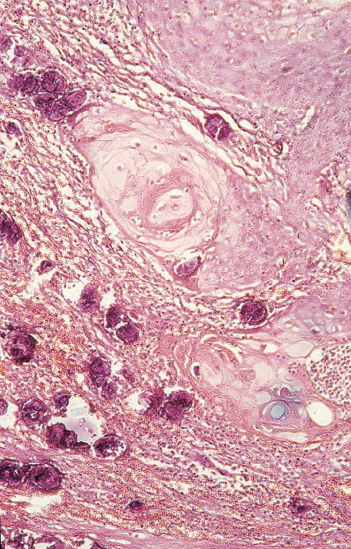

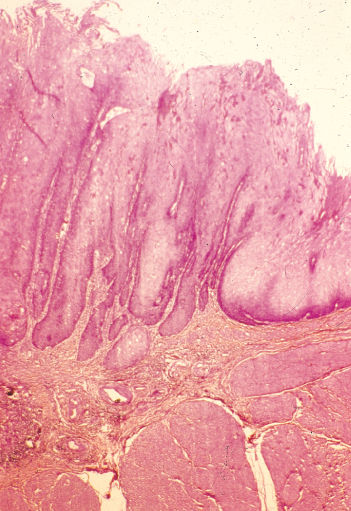

Significant changes in the pathological types of schistosomiasis-associated bladder tumors have been found over the past decades.10 Comparing the periods 1962–1967 and 1987–1992, there was a decrease in the incidence of nodular tumors (83.4% to 58.7%) and of SCC (65.8% to 54.0%) but an increase in the incidence of papillary tumors (4.3% to 34.8%) and TCC (31.0% to 42.0%).63–65 Similar results were proved by comparing the periods 2001–2005 and 2006–2010 as was fore-mentioned.22 The extent of Schistosoma infection apparently plays a significant role in the induction of different types of carcinoma; SCC is usually associated with moderate and/or high worm burdens, whereas TCC occurs more commonly in areas associated with lower degrees of infection63–65 (Figure 1). Adenocarcinoma of the bilharzial bladder is particularly aggressive owing to its proneness to develop gross chromosomal aberrations combined with high cell proliferation.66 Another rare, though distinct, variant of SCC is verrucous carcinoma of the bilharzial bladder (Figure 2). Despite reports to the contrary, a large proportion develop into invasive SCC, with which they share the same adverse prognosis.67

Figure 1 Bilharzial bladder cancer. Infiltrating, well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma with adjacent calcified S. hematobium eggs (H&E ×100).

Source: Courtesy of Drs M.R. Mahran and M. El-Baz, Mansoura University, Egypt.

Figure 2 Verrucous carcinoma (noninvasive) of bladder with superficial filamentous elongated surface projections (H&E ×40).

Source: Courtesy of Drs M.R. Mahran and M. El-Baz, Mansoura University, Egypt.

Experimental data for BBC

In a number of nonhuman primates, infection with S. haematobium resulted in epithelial proliferation, squamous metaplasia, and TCC of the urinary bladder.68 These types of carcinoma were morphologically similar to those observed in human bladders,69 and such observations suggest that there is an association between S. haematobium and BC. These early experimental observations were important because eggs of S. haematobium, lyophilized worms, and urine from bilharzia patients have not been found to be carcinogenic to mice.70, 71 However, 2-acetyl-aminofluorene appears to promote malignant and benign bladder neoplasms of mice infested with schistosomes more often than does either agent alone.72 Cancer development was thought to have been accelerated by schistosomal infection, presumably acting as a late-stage cocarcinogen by virtue of its direct proliferative effect on the urothelium.73

Schistosomiasis and cancer of other sites

Large intestine

Intestinal infestation with S. japonicum in Asia is considered a significant contributory factor to the development of colorectal cancer (CRC). Female S. japonicum lays a very large number of eggs (2000 per day per pair of worms), whereas S. mansoni‘s eggs are considerably less numerous and, thus, cause fewer pathologic problems.74 In Shanghai, patients with intestinal schistosomiasis and cancer of the large intestine are, on average, 6 years younger than patients with spontaneous intestinal cancer. Furthermore, the male-to-female ratio of schistosomal CRC is consistently higher than in nonschistosomal cancer.75, 76 Recently, Madbouly et al.76 studied the S. mansoni-associated CRC and showed that it has distinctive pathological features often similar to those of colitis-induced carcinoma. The parasitism is strongly associated with microsatellite instability, which is a sign of defective DNA repair,77 which in turn affects normal colonocyte homeostasis resulting in malignant growth.78 Another study showed that S. mansoni-associated colorectal tumors are characterized by Bcl-2 overexpression and less apoptotic activity than ordinary colorectal tumors.79

The liver

A study of liver cancer and its association with a previous diagnosis of schistosomiasis was performed in rural Sichuan, China. Previous schistosomal infection was found to be significantly associated with liver cancer and that a fraction of the disease (27%) was attributable to schistosomiasis among hepatitis-negative population.80 Experimental data showed remnants of schistosomal eggs in the severe granulomatous reaction present within a well-differentiated hepatocellular carcinoma that had developed in a hepatitis-B and -C, seronegative chimpanzee.81

Lymphoma

The association between schistosomiasis and lymphomas is far less reported.82 Occurrence of an isolated, primary T-cell lymphoma of the bladder may represent an unusual immune response to schistosomiasis.83 Discrete case reports of lymphoma in patients with hepatosplenic and chronic intestinal infections with S. mansoni and S. japonicum have been known. Types detected were histiocytic lymphoma84 and large B-cell lymphoma;82, 85, 86 where lymphoma cells proliferated around egg emboli and adult worms.86

Other organs

Immunohistochemical studies confirmed invasive SCC of the prostate in three prostatic schistosomiasis patients coming from a population where prostatic cancer is uncommon.87 Mazigo et al.88 reported three cases of adenocarcinoma of the prostate gland associated with S. haematobium in Tanzania.

A case report of a 34-year-old white woman was suspected for genital cervical schistosomiasis. A cervical smear showed cytologic changes suggesting dysplasia and S. haematobium eggs inside the chorion surrounded by granulomatous inflammation. The patient showed marvelous response to praziquantel, and all clinical and histopathological changes were relieved. It was concluded that cervical schistosmiasis should be considered a curable cause of dysplasia. It was postulated that schistosomiasis of the cervix might play an additional role in HPV-induced cervical dysplasia and cancer.89

Evaluation of carcinogenicity of schistosomiasis

According to accepted international criteria, infection with S. haematobium is carcinogenic to humans (group 1); infection with S. mansoni is not classifiable as to its carcinogenicity to humans (group 3); and infection with S. japonicum is possibly carcinogenic to humans (group 2B).90

East Asian distomiasis

Liver and pancreas

Clonorchiasis and opisthorchiasis are caused by chronic infection of the human liver flukes in the biliary tree. The three species of flukes Clonorchis sinensis, Opisthorchis viverrini, and Opisthorchis felineus are closely related trematodes that have similar life cycles and they cause the same pathophysiology to the biliary tract.91 Globally, nearly 35 million people are infected with C. sinensis, with approximately 15 million being in China.92 Clonorchiasis is predominantly endemic in China, the Republic of Korea, Vietnam, and a part of Russia.93 A similar species, O. viverrini, causes distomiasis in Thailand. Cholangiocarcinoma (CCA) is a cancer of the bile ducts that is considered the most severe complication of liver fluke infection. Exceptionally high incidence of CCA in Thailand and Korea is strongly related with the high prevalence of opisthorchiasis and clonorchiasis91; hence, C. sinensis and O. viverrini have been classified as “carcinogenic to humans” (Group 1) by the IARC in 2009.94, 95 However, infection with O. felineus is not classifiable as to its carcinogenicity to humans (group 3).94–96 The highest recorded incidence of CCA in the world is present in North-eastern Thailand, where 70–90% of the population are infected with O. viverrini. In Korea, where infestation with C. sinensis is widely prevalent, CCA accounts for more than 20% of liver cancers.

Intraductal papillary neoplasm of the bile duct is known to be a premalignant condition often associated with mucin over-production. There have been a few recent articles revealing that the disease was related with C. sinensis infection. Suh et al.97 reported that 5 of 16 (31%) of intraductal papillary tumors of the bile duct were associated with C. sinensis infection. Jang et al.98 reported that when CCA was associated with C. sinensis infection, intraductal papillary neoplasm was much more common than the usual adenocarcinoma.

Human infection results from eating raw or undercooked parasitized freshwater fish. In humans, the ingested parasites excyst in the duodenum and ascend the bile ducts and canaliculi, where they mature, causing biliary epithelial hyperplasia and fibrosis. Promotors of carcinogenesis as nitroso compounds are incriminated. In the Far East, nitrosamines are commonly found in traditional Chinese preserved foods such as salted fish, dried shrimp, and sausage.99 Precursors of nitroso compounds have been identified in the body fluid of men infested with O. viverrini.100 Pancreatic ducts may also be infected with C. sinensis; this frequently results in squamous metaplasia and mucous gland hyperplasia.

Malaria

The geographic distribution of BL in the classic malarial belt initially suggested the possible role of an arthropod vector in oncogenesis.101, 102 BL is a highly aggressive B-cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma and is the fastest growing human tumor.103 Two major epidemiological clues to the pathogenesis of BL are early infection by Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) and the geographical association with malaria. Both agents cause B-cell hyperplasia, which is almost certainly an essential component of lymphomagenesis in BL. Recent figures suggest that the incidence in children in equatorial Africa is similar to that of acute lymphoblastic lymphoma (ALL) in high-income countries—probably of the order of 3–6 per 100,000 in children aged 0–14 per year, accounting for 30–50% of all childhood cancers in equatorial Africa. This correlates with the high frequency and intensity of malaria in young children.104 Incidence figures from other parts of the world, though limited, are considerably lower than those in equatorial Africa.105 These data give the disease its name in Africa, endemic Burkitt lymphoma (eBL).

The possibility that drugs taken for malaria prophylaxis could have contributed to the development of BL106, 107 was considered unlikely because no increase (and indeed a decrease) in eBL was observed in the Malagasy Republic108 and in Imesi, West Africa,109 where intensive antimalarial prophylaxis was practiced. Interestingly, recent studies showed that chloroquine could play a role in cancer prevention.110, 111 Within endemic areas, the peak incidence of BL follows closely the incidence of severe Plasmodium falciparum malaria, and malarial prophylaxis reduces the incidence of the lymphorna.108, 109

Of considerable interest are studies on the frequency of sickle-cell trait in eBL patients and controls. Persons with sickle trait are protected against the lethal effect of overwhelming P. falciparum malaria in early childhood and from the intense reticuloendothelial stimulation that sometimes progresses to hyper-reactive malarial splenomegaly.112 Sickle cells exposed to low oxygen tension do not support the growth of parasites in vitro. A similar phenomenon may explain why children with the sickle-cell trait have a lower P. falciparum parasitemia. As a result, a lower mortality rate, lower IgM levels, and reduced lymphoproliferation (as measured by spleen size) are found among individuals with hemoglobin AS genotype. However, most studies attempting to relate eBL to AS hemoglobinopathy have failed to reach statistical significance.113, 114 Other hemoglobinopathies, such as hereditary ovalocytosis, also protect against malaria. If eBL turns out to be underrepresented in populations where both ovalocytosis is prevalent, as in Papua, New Guinea,115 such information would provide strong supporting evidence for malaria as a cofactor in the genesis of eBL.113

One way of explaining the observation that the malaria patient harboring a multitude of parasite-derived antigens becomes a host susceptible to eBL is the suggestion that malaria patients produce so many nonspecific and “useless” antibodies that they are unable to recognize and respond to the threat posed by a small clone of malignant lymphoid cells.116

Malaria and EBV

More significant are the epidemiologic observations that have linked eBL to the potentiating effect of malaria on EBV infection.117 Endemic BL is only found in areas where malaria is holoendemic or hyperendemic; and within these areas, it is absent in malaria-free pockets, such as urban centers. Vigorous cellular and serologic responses occur during malarial infection.118 This renders the plausible argument that persistent reticuloendothelial stimulation experienced among malarial populations conditions the EBV-infected African patient to develop a neoplasm rather than a self-limited disease, such as infectious mononucleosis.119 The potentiation effect adopted by malaria to induce BL is B-cell hyperplasia. A cystein-rich-inter-domain-region1alpha (CIDR1a) of the Plasmodium falciparum erythrocyte membrane protein 1 (PfEMP1) is expressed on the surface of infected erythrocytes. This protein was shown to cause an increase in the number of circulating B cells carrying the EBV in acute malaria.120, 121 This was explained by two mechanisms; first, the protein stimulates B memory cell replication, including the B-cell compartment where EBV resides.122 Second, CIDR1a can induce virus production from infected B cells, which in turn leads to infection of other B cells.122–124 Acute malaria, which increases B-cell proliferation, also impairs EBV-specific T-cell responses.101, 113, 125 This results in a larger pool of EBV-infected cells with increased likelihood for chromosomal translocation and lymphomagenesis.126 Chattopadhyay et al.127 defined a malaria-associated aberration localized to the EBV-specific CD8+ T-cell compartment.

African children with eBL develop autoantibodies, the elevated titers of which show no linear correlation with EBV titers for viral capsid antigen (VCA) or EBNA128 suggesting that a factor independent of EBV causes an immunologic imbalance and autoantibody production. The notion that this could be due to malaria is supported by the observation that Caucasians suffering from acute P. falciparum malaria develop autoantibodies,129, 130 and in vitro experiments that demonstrated that normal human lymphocytes can produce autoantibodies as a response to malarial antigens.131

Chromosomal aberrations and lymphomagenesis

Overexpression of c-myc appears to be central to the pathogenesis of typical and atypical BL. Although c-myc translocation occurs in all cases of BL, differences are seen in the translocation patterns in the endemic and sporadic varieties of the disease. Typically, sporadic BL has translocations involving sequences within or immediately 5′ to myc on chromosome 8 and sequences within or near the immunoglobulin heavy chain S region on chromosome 14. In contrast, eBL tends to be characterized by a translocation involving sequences on chromosome 8 further upstream from myc and sequences within or near the JH region on chromosome 14.131 A mechanism by which malaria can directly produce chromosomal translocations associated with BL is the interaction with toll-like receptors (TLRs),104 which are stimulated in malaria infection by certain agonists such as haemozoin and CpG-enriched DNA, and, in turn, activate the adaptive immune system. This is explained by their ability to induce activation-induced cytidine deaminase (AID) in B cells, an enzyme that induces hyper-variable region mutations and class switch recombination as well as activating B lymphocytes.132–134

Recent evidences

Several studies demonstrated the relationship between several parasites and oncogenesis, for example, the relation between cryptosporidiosis and intestinal cancer.135, 136 The study done by Certad et al.135 was the first to record that a human-derived Cryptosporidium parvum isolate can induce cancer in mice. Another protozoan Trichomonas vaginalis was incriminated. Although the latter has a possible role in cancer of the cervix, its role in prostatic cancer is still arguable.137 Neurocysticercosis was also incriminated in hematological malignancies.138 Parasite-induced immunomodulation, DNA damage, and nitric oxide release due to chronic inflammation were the mechanisms proposed.139 The relationship of the nematode Strongyloides stercoralis to hepatobiliary cancer140 and Kaposi sarcoma141 was studied, as well as the role of Toxoplasma gondii in brain cancer142, 143 and lymphoma.144 These parasites and others were incriminated in cancer development; however, clues are not yet sufficient to include them in the IARC roster.137

In view of recent revaluation of the role of parasites, it was found that infectious agents and their products can orchestrate a wide range of host immune responses, through which they may positively or negatively modulate cancer development and/or progression. Interestingly, certain types of pathogens, including parasites, can decrease the risk of tumorigenesis or lead to cancer regression.145 Trypanosoma cruzi was found to decrease the incidence of experimentally induced rodent colon cancer.146 The nematode Trichuris suis was investigated clinically and experimentally for its ability to alleviate diseases, such as inflammatory bowel disease (ulcerative colitis, Crohn disease), multiple sclerosis, and allergy.147, 148 The applicability of this to cancer pathology, and more specifically to tumors of the gastrointestinal system, is a question open to future investigations.145

Summary

When uncommon neoplasms are noted with undue frequency in countries with a high prevalence of parasitic diseases, parasites become incriminated. Many parasites were studied for a possible role in oncogenesis; however, not all of them were registered as true carcinogens by the IARC. Chronic inflammation, immunomodulation, overexpression of certain carcinogens, DNA mutations, and suppression of apoptosis are the frequent well-common mechanisms for parasite-induced oncogenesis. Besides, concomitant presence of other infectious agents is proved to be an enhancing factor in many situations. Epidemiological, cytogenetic, and animal studies were used to prove the relationship between parasites and cancer. In this view, S. haematobium was proved to play an important role in developing urinary BC due to chronic irritation by submucosal egg deposition, constant high levels of N-nitroso compounds that lead to DNA mutations, suppression of apoptosis, and, hence, histopathological changes in the urinary epithelium. Human papilloma virus is still suspected to play an assistant role in this sequence. Other Schistosoma species S. japonicum is classified as a colorectal carcinogen especially in the Far East. Other helminthes Clonorchis and Opisthorchis are proved to induce hepatobiliary cancer. In Africa, a strong correlation between BL and EBV infection is present, with an evident enhancing role for P. falciparum. These and more can be viewed as possible human carcinogens in respect of chronic inflammatory process associating several parasitic infections. However, strong evidences, especially cytogenetic, are usually required. Strikingly, despite the above-mentioned data, it seemed that certain parasites can modulate the host immune response in a manner that could lead to cancer regression or prevention. This is in the prospect of revaluation of the clinical importance of infectious agents; an issue that requires future concern.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree