PARACHIASMAL LESIONS

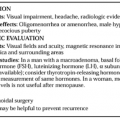

Most chiasmal syndromes are caused by extrinsic masses: classically, pituitary adenomas, suprasellar meningiomas, craniopharyngiomas, and internal carotid artery aneurysms. Although certain patterns of vision failure may suggest the location and type of lesion, such clinical impressions often prove fallible in the face of neuroradiologic procedures (and at craniotomy). At any rate, the diagnostic evaluation of all nontraumatic chiasmal syndromes is stereotyped: to rule in or out the presence of a potentially treatable mass lesion. Inflammatory or infectious causes are extremely rare, and chiasmal involvement by head trauma or radionecrosis is uncommon. The distinction is made by age-related incidence; accompanying signs and symptoms; and typical, if not diagnostic, radiologic appearance.

OPTIC AND HYPOTHALAMIC GLIOMAS

Primary astrocytic tumors of the anterior visual pathways assume two major clinical forms: the relatively benign glioma (juvenile pilocytic astrocytoma) of childhood and the rare malignant glioblastoma of adulthood. With the exception of vision loss and anatomic location, these two groups have little in common, and the assumption that the progressive malignant form stems from the static childhood form is untenable.

For the indolent glioma of childhood, clinical presentation is predicated on the location and extent of the tumor. Gliomas may be separated into roughly three topographic groups: unilateral optic nerve (orbital, intracranial, or both, but not involving the chiasm); principally chiasmal mass; or simultaneous infiltration of the hypothalamus. Strictly intraorbital gliomas present as insidious proptosis of variable degree, and although vision is usually diminished, remarkably good vision function is not uncommon. Strabismus, disc pallor, or disc swelling may be observed. Progressive proptosis, even if abrupt, or increased visual deficit does not imply an aggressive activity of the tumor, a hemorrhage, or necrosis. These tumors may rarely extend intracranially and have a low (˜10%) mortality rate.46

Chiasmal gliomas are more common than the isolated orbital type. These tumors present with unilateral or bilateral vision loss, strabismus, optic atrophy, and/or infantile nystagmus. The nystagmus may mimic spasmus nutans (usually unilateral or asymmetric nystagmus), complete with head nodding and torticollis, or may show a coarse, conjugate mixed horizontal–rotary pattern, especially when vision is severely defective. “Seesaw” nystagmus may also rarely be seen in these patients.

Children with extensive basal tumors also show hydrocephalus and signs and symptoms of increased intracranial pressure. Hypothalamic signs include precocious puberty, obesity, dwarfism, hypersomnolence, and diabetes insipidus. Usually, the non-vision complications of extensive gliomas occur in infancy or early childhood, and onset of obstructive signs or hypothalamic involvement much beyond the age of 5 years is uncommon.

Gliomas of the optic nerves and chiasm may be associated with neurofibromatosis in 20% to 40% of cases; the patients either show other characteristic stigmata or have affected relatives.47, 48 and 49 Indeed, there is good evidence that children with neurofibromatosis type 1 and chiasmal gliomas have a better long-term prognosis than those with chiasmal gliomas alone.46 Absence of neurofibromatosis, electrolyte abnormalities, and intracranial hypertension are all indicators of a poor prognosis.50,51

Treatment of benign optic gliomas in childhood is somewhat controversial, with most pediatric and neuro-ophthalmologists favoring a conservative approach. When there is documented progressive vision loss, significant tumor growth, or obstructive signs, intervention is obviously indicated. Debulking surgery, radiation therapy, and chemotherapy have all been advocated. Newer radiation techniques may allow a higher percentage of treated patients to grow normally,52 and, when chemotherapy is indicated, reports suggest success with a combined carboplatin/vincristine regimen,53 as well as oral etoposide (VP-16).54

DIENCEPHALIC SYNDROME

When the hypothalamus is the site of childhood glioma, a dien-cephalic syndrome evolves.55 Findings consist of emaciation, despite adequate food intake, that develops after a period of normal growth; hyperactivity and euphoria; skin pallor (without anemia); hypotension; and hypoglycemia. Other notable signs include nystagmus and disc pallor, to which may be added sexual precocity and laughing seizures.56 Twelve cases of histologically proven opticochiasmatic glioma with diencephalic syndrome were culled from a 22-year review.57 There were 6 men and 6 women, all with “failure to thrive” but with normal linear growth; none had stigmata of neurofibromatosis. Two patients died in the immediate postoperative period, and 10 patients received radiotherapy with “reversal of their diencephalic syndrome” (weight gain, deposition of subcutaneous fat, normal development). Six of 10 are alive, 3 being considered normal, and 3 are blind, retarded, or both. Clinical evidence of bilateral optic nerve involvement was seen in 10 of these 12 cases, but it was not possible during surgery to determine the origin of these tumors. The diencephalic syndrome appears to be related to the age at which the hypothalamus becomes compressed; none of the 12 patients (and only 4% of all published cases) had onset of symptoms after 2 years of age. Craniotomy with biopsy and radiotherapy is often indicated, as tumors involving the hypothalamus appear to be larger and more aggressive than other astrocytomas arising in this region.58

RADIOLOGIC INVESTIGATION OF GLIOMAS

The radiologic investigation of suspected gliomas is now sophisticated to the extent that “neuroradiologic biopsy” may obviate tissue diagnosis. The typical, but variable, findings

include CT and MRI evidence of enlarged orbital or intracranial optic nerves; enlarged chiasm; a homogeneous hypothalamic mass; enlarged optic canals; and J-shaped or gourd-shaped sellae. The demonstration of such typical dysplastic changes of the sella turcica and optic canals, coupled with CT or MRI evidence of intrinsic chiasmal mass, so strongly suggests the diagnosis of glioma that histopathologic affirmation probably is superfluous and hazardous to vision.

include CT and MRI evidence of enlarged orbital or intracranial optic nerves; enlarged chiasm; a homogeneous hypothalamic mass; enlarged optic canals; and J-shaped or gourd-shaped sellae. The demonstration of such typical dysplastic changes of the sella turcica and optic canals, coupled with CT or MRI evidence of intrinsic chiasmal mass, so strongly suggests the diagnosis of glioma that histopathologic affirmation probably is superfluous and hazardous to vision.

Analysis of visual fields in patients with chiasmatic gliomas has shown no consistent relationship between the pattern of field defects and the location, size, or extent of tumor; in 12 of 20 patients, the putative bitemporal pattern of chiasmal involvement was absent.59 Central scotomas or measurable depression of the central field occurred in 70% of the eyes; therefore, the absence of bitemporal hemianopia, or one of its variants, cannot be interpreted as a sign that the glioma does not involve the chiasm.

CRANIOPHARYNGIOMAS

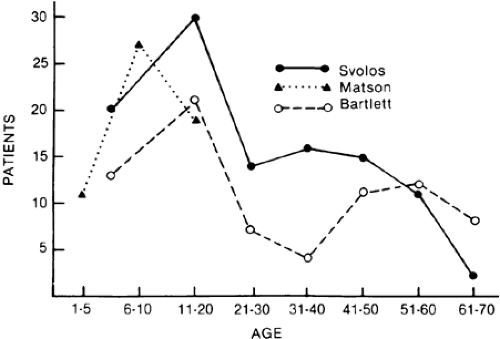

Craniopharyngiomas (see Chap. 11) are developmental tumors that arise from vestigial epidermoid remnants of Rathke pouch, scattered as cell nests in the infundibulohypophysial region. These tumors are usually admixtures of solid cellular components and variable-sized cysts containing oily mixtures of degenerated blood and desquamated epithelium or of necrotic tissue with cholesterol crystals. Calcification of such debris may be radiologically detectable, a helpful diagnostic sign. In rare instances, these tumors may present in the neonate, attesting to their congenital origin.60 Craniopharyngiomas constitute 3% of all intracranial tumors (˜15% in children), with two distinctive modes of presentation—in childhood and in adulthood—with a peak in the 40- to 70-year-old age range (Fig. 19-11).

The symptomatology of childhood craniopharyngioma is variable, depending on the position and mass of the tumor.61,62 Frequently, progressive vision loss goes unnoticed until a level of severe impairment is reached, or unless headache, vomiting, or behavioral changes occur because of hydrocephalus. Obesity, delayed sexual development, somnolence, and diabetes insipidus attest to hypothalamic dysfunction, and other endocrinopathies may be present. Increased intracranial pressure is not uncommon, and papilledema may be observed. Some optic atrophy is usually present, but its absence does not conflict with the presence of chronic compression of the anterior visual pathways, even with severe vision loss. Suprasellar or intrasellar calcification is a rather constant radiologic finding in childhood craniopharyngiomas, occurring in 80% to >90% of affected children. Cystic areas frequently occur in craniopharyngioma but rarely in opticochiasmatic gliomas. CT scanning retains special sensitivity in diagnosis, being superior to MRI in detecting calcifications and cyst formations. However, involvement of adjacent structures is more clearly defined by MRI.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree