Palliative Care for the Child with Cancer

Christina K. Ullrich

Barbara M. Sourkes

Joanne Wolfe

Life is so strange. Sometimes you feel it’s like a book with chapters to fill, never ending.

Sometimes it’s like a chess game where you have to make each move so carefully.

Other times it’s like a mystery where each hidden chamber reveals its secrets.

It is even a war where to live it is to win it.

—Karen Beth Josephson, age 10.1 (p. 23)

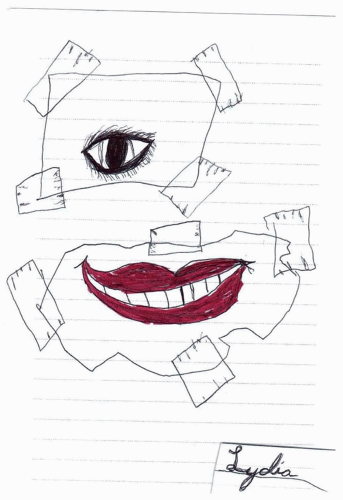

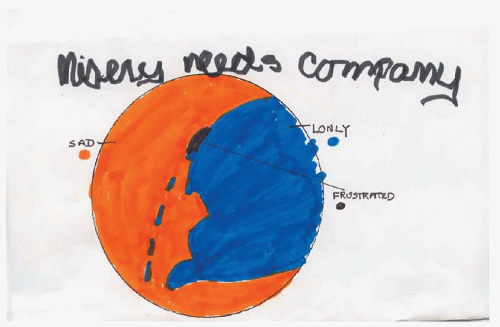

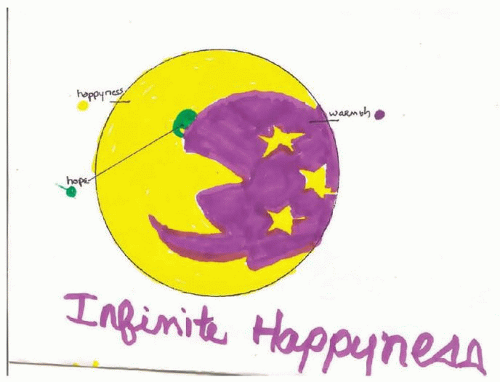

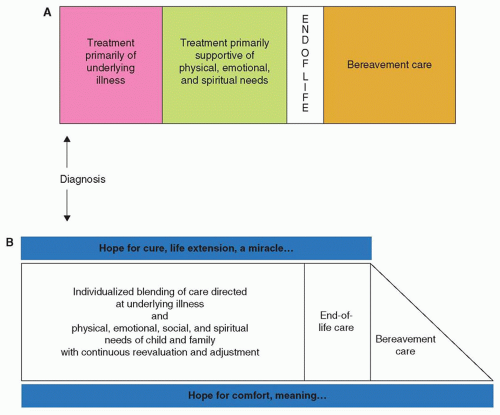

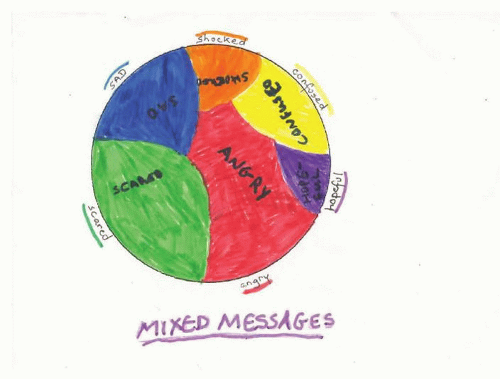

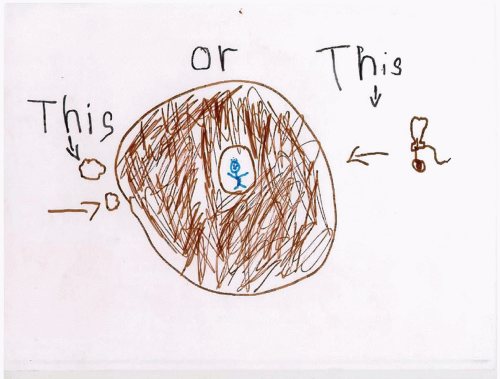

These profound and poignant opening words exemplify the experience of the child living with a life-threatening condition. The child’s diagnosis fractures any certainty, normalcy, and stability that may have existed (Fig. 50.1). Vigilance, determination, and hope mark the uncharted horizons that lie ahead for both the child and the family. From an emotional point of view, the child with advanced cancer faces extraordinary life circumstances and longs for understanding and comfort (Figs. 50.2 and 50.3).

PALLIATIVE CARE: A PHILOSOPHY OF CARE

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), palliative care for children with life-threatening conditions is the active total care of the child’s body, mind, and spirit, while also supporting the

family. It begins when a serious illness is diagnosed, and continues regardless of whether or not a child receives treatment directed at the disease or underlying condition. A palliative care philosophy is rooted in continual evaluation and optimization of a child’s physical, psychological, and social well-being and that of the family.

family. It begins when a serious illness is diagnosed, and continues regardless of whether or not a child receives treatment directed at the disease or underlying condition. A palliative care philosophy is rooted in continual evaluation and optimization of a child’s physical, psychological, and social well-being and that of the family.

This approach to the care of children with cancer has become an accepted standard of care. According to the American Academy of Pediatrics, “Excellence in pediatric palliative care is essential for hospitals and other facilities caring for children. Program development in pediatric palliative care, along with community outreach and public education, must be a priority of tertiary care centers serving children.”2 Furthermore, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) published a comprehensive report on improving palliative and end-of-life care for children and their families in 2003 calling for improvements in all aspects of care including clinical models, education, finance restructuring, and research.3 “Dying in America: Improving Quality and Honoring Individual Preferences at the End of Life” an IOM report on the delivery of health care to individuals approaching death and their families, is forthcoming.4 Indeed, high-quality palliative care is an expected standard in both pediatrics and oncology.2,3,5

Effective palliative care requires a broad interdisciplinary approach that includes the family, makes use of available community resources, and can be successfully implemented even if resources are limited. It can be provided across care settings, including home and tertiary hospital settings. Notably, palliative care is primarily delivered by the primary interdisciplinary oncology team. For more complex considerations, families and clinicians may benefit from subspecialty palliative care consultation. While palliative care services are increasingly available, they are largely hospital-based and not yet ubiquitous. A recent survey of Children’s Hospitals revealed that 69% had a pediatric palliative care program.6 With regard to the pediatric oncology population, a 2008 study found that a palliative care team existed in only 58% of Children’s Oncology Group centers.7

The Interdisciplinary Nature of Palliative Care

The care of a child with advanced cancer is best met through an interdisciplinary team, working to address the physical, emotional, and spiritual needs of the child, parents, siblings, and community. The trained interdisciplinary team should recognize the long-term needs of families and ensure continuity of service through time, fostering open communication, intensive symptom management, psychosocial and spiritual support, and timely access to care, with the primary goal of enabling meaningful experiences.

PALLIATIVE CARE FOR CHILDREN WITH CANCER

Although survival outcomes are improving, approximately 20% of children diagnosed with cancer eventually die of their disease.8 Cancer remains the leading cause of nonaccidental death in childhood.9 Children with advanced cancer, who ultimately die from their disease, as well as their families, are likely to benefit from the added layer of support that palliative care provides. However, requiring such prognostic certainty (i.e., death is certain and/or near) can result in lost opportunities to maximize support for children and families.

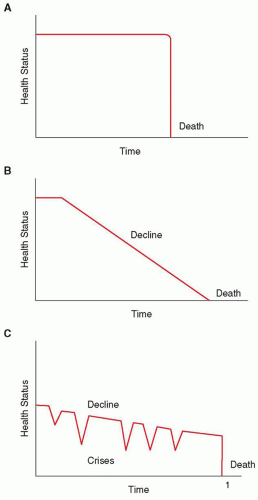

For children with cancer, it is not always possible to determine whether the disease will be responsive to cancer-directed therapy, nor is it possible to determine which type of trajectory the dying process will take (Fig. 50.4).10 Some children may die suddenly and unexpectedly— for example, the child undergoing bone marrow transplant who experiences a treatment-related complication (Fig. 50.4A). Others may experience a steady and fairly predictable decline (Fig. 50.4B), such as the child with a progressive brainstem glioma after radiation therapy. Most children with progressive cancer will experience varying periods of chronic illness punctuated by crises, one of which may prove fatal (Fig. 50.4C). An example of this type of trajectory may involve a child with relapsed metastatic neuroblastoma who may live years before experiencing a life-ending event.

In the context of such prognostic uncertainty, a palliative approach may not be integrated until late in the illness trajectory (Fig. 50.5A). There are likely multiple possible reasons underlying this delay. First, a common misunderstanding of palliative care is that it should be reserved for instances in which the outcome is certain (child will not survive and is approaching the end of life). As a result, care for children with cancer tends to focus solely on life-extending treatment until late in the illness trajectory, as opposed to concurrent integration of care aimed at maximizing comfort and quality of life for the child and family (Fig. 50.5B). Thus, optimal care of the child with life-threatening illness requires recognition on the part of the care team that it may not be clear if or when a child is dying, but if death is a potential outcome, palliative care in advance of the end of life should be a priority.

Another challenge to the timely integration of palliative care is the viewpoint that palliative care can only be implemented to the exclusion of disease-directed therapy. This is one of the most common reasons for pediatricians to delay referral to a palliative care program.11 For children with cancer, cancer-directed therapy is commonly pursued late into the course of illness, even when the child is unlikely to be cured.12,13 An “either or” approach delays introduction of palliative care and also promotes an abrupt transition from life-prolonging to symptom-oriented care (Fig. 50.5A).14 If palliative care is conceptualized as always being a part of the care paradigm (Fig. 50.5B), there is no transition or conflict between cancer treatment and palliative care. This approach is supported by the views of parents of children with cancer, who favor concurrent pursuit of cancer-directed therapy and optimizing child quality of life.12,15,16 Understanding that palliative care is not synonymous with hospice or end-of-life care facilitates the timely referral to a palliative care program, should the need arise, even as disease-directed or life-prolonging measures are pursued. Of note, end-of-life care (as depicted in Fig. 50.5) may be considered a distinct phase for children who are almost certainly going to die. For children with a prognosis of 6 months or less, hospice programs can provide care that in many ways is palliative care, with a stronger emphasis on home-based and comfort-focused care, even though cure, life extension, or praying for a miracle may be continued hopes of the family.

When discussing referral to a palliative care team, presenting palliative care as an added resource that both supports the family’s goals, and maintains an eye to the child’s and family’s well-being is often the most helpful approach. A useful strategy is to introduce the concept of palliative care in the context of “thinking through options,” “planning for now or the future,” “adding a layer of support for your child and family” and “helping your child feel as well as possible.” Families also appreciate reassurance that a palliative care team typically partners with the extant oncology team without replacing them, to provide maximal support for the child and family. Presenting palliative care as a “redirection of care” does not adequately reflect the nature of palliative care, and is less likely to be well received by families.

Communication: Goals of Care, Prognosis, and Advance Care Planning Conversations

Delineation of Goals of Care

A “goals of care conversation” is the primary “procedure” utilized by clinicians to further integrate a palliative approach into the care of children with advanced cancer. To begin a discussion with patients and families about care goals, it is often helpful to start with open-ended questions such as: What concerns you most about your child’s illness? How is treatment going for you/your child and your family? As you think about your/your child’s illness, what is the best and the worst that might happen? What are your/your child’s hopes (expectations, fears) for the future? These open-ended questions provide a means to explore the family’s illness experience and their prognostic understanding, as well as their hopes and goals within this context.

As with other conversations with families, discussing goals of and options for care necessitates sensitivity to and empathy for the child and family’s concerns and readiness (time and timing), attunement to their spoken and nonspoken cues, respect for their cultural/spiritual beliefs, and a nonjudgmental attitude on the part of the team are critical. Hope is a universal underpinning of communication17,18 and is a central factor for parents of children with advanced cancer making decisions. Whatever the meaning of hope for the child and family at that point in time (e.g., hope for life extension concurrent with hope for comfort), it is essential to convey a sense of hope.

Prognosis

Wolfe et al.15 have shown that parents first recognize that the child has no realistic chance for cure more than 3 months after the primary oncologist realizes this fact. However, the study also showed that earlier recognition by the physician and parent that the child had no realistic chance for cure was associated with better integration of strategies focused on enhancing child comfort. Thus, early and ongoing discussions aimed at informing parents of the possibility of a child’s death may be critical to easing suffering during the end of a child’s life.

Much has been written about strategies for communicating difficult news (i.e., limited prognosis).19 Recommendations have focused on ensuring privacy and adequate time; assessing the families’ understanding of the condition; providing information simply and honestly; encouraging patients and parents to express their feelings and empathizing with them; and providing a plan for approaching the situation and a summary of what was discussed. It is critical to end such discussions by assuring the family that they will receive ongoing support and that there will be opportunities for additional discussions to address continued concerns.

Cancer-Directed Therapy

Many families opt for continued treatment of the underlying cancer even when there is no realistic prospect for cure12,15,16 and parent preference for continuing treatment is a key factor for the pediatric oncologist’s prescription of such chemotherapy.13 Labeling cancer-directed therapy as either “curative” or “palliative” is often an artificial delineation and these labels undermine the term palliative, equating it with no hope for cure. Furthermore, no matter what the intent, the outcome of treatment is often uncertain. The rationale of the parents and child for ongoing cancer-directed treatment may include hoping for cure (perhaps via praying for a miracle) and hoping to extend the child’s life, and hoping to ease symptoms related to progressive disease. Wolfe et al.15 found that only 13% of parents reported that the primary goal of cancer-directed therapy for their child during the end-of-life care period was to lessen suffering. The majority of parents maintained a primary goal of extending life. Accordingly, communication about this issue must be very clear and tailored to the individual family.

In discussions of treatment options with families, the rationale for continued cancer-directed therapy might be presented as, “We are hoping that this treatment will control your child’s cancer for as long as possible, perhaps long-term, and at the same time, will help your child feel better.” At times, when families disclose praying for a miracle, a response might be “The very nature of miracles is that they are rare. However, we have seen miracles, and they have occurred both on and off treatment.” In other words, a child need not continue cancer-directed therapy to preserve hope, especially when the therapy significantly impacts the child’s quality of life.

Chemotherapy. Continuation of chemotherapy without the goal of cure or for very advanced cancer needs to be carefully considered, weighing the potential for life extension and the impact on quality of life. Several studies show improved quality of life among adult patients with advanced cancer receiving chemotherapy compared to those who were not.20,21,22 Possible reasons for this include placebo effect, provision of hope, or increased medical attention associated with being on treatment. The role of continued cancer treatment in children with advanced cancer has not been well studied. The benefits may depend on the developmental stage of the child and his or her awareness of disease state.

Phase I Trials. The goal of phase I research is to determine the toxicities and maximum-tolerated doses of an investigational agent. Yet, many parents considering a phase I trial for their child are unable to state the purpose of the trial. They also found that adults with cancer who participate in phase I trials are strongly motivated by the hope of therapeutic benefit. This is also true of parents of children with advanced cancer23 as well as adolescents with cancer.24 Yet overall, the chance of tumor response in phase I trials is low.25

Similar to discussions about chemotherapy, it is critical to ensure effective communication when discussing phase I therapy for children with advanced cancer. In general, physicians tend to assume there is a more positive potential benefit from experimental chemotherapy than the data would warrant. While pediatric oncologists may report presenting phase 1 trials as an option rather than a recommendation,26 parents emerging from such discussions describe optimism that may not be commensurate with the clinical reality.27 Given these challenges, further consideration for linking palliative care support with enrollment in phase I trials is warranted.28

Radiation Therapy. In addition to pain, common indications for radiation include treatment of bleeding, fungation, and ulceration; relief of impeding or actual obstruction; and shrinkage of symptomatic tumor masses. Given with the intent of relieving symptoms, and without significant concern for late effects, radiation for children with advanced cancer is typically delivered in larger fraction sizes over shorter time frames.29 Single-fraction regimens, when compared with multiple-fraction regimens, provide equal disease control with lower medical and societal costs.30 In the pediatric population, studies evaluating radiation in advanced cancer are sparse. Retrospective reviews of children with metastatic Ewing sarcoma or advanced neuroblastoma indicate that 70% to 80% of children receive at least a partial reduction in pain with radiation therapy.31,32 Although infrequently used in pediatrics, radiopharmaceuticals can effectively reduce bone pain. For example, treatment of children with highly refractory neuroblastoma with low-dose 131I-meta-iodo-benzyl-guanidine (131I-MIBG) has been reported to relieve tumor-associated pain.33

Resuscitation Status

Discussion of whether to attempt cardiopulmonary resuscitation for children with advanced cancer is a challenging and emotional topic. Pediatric clinicians also view unrealistic parent expectations or differences understanding of their child’s as major barriers to advance care planning discussions.34 For these reasons, medical caregivers may defer these conversations until respiratory or cardiac collapse seems imminent. Clearly, parents would be better able to consider this decision if they were not in the midst of a medical crisis. This issue should be broached in advance, whenever possible, so that parents have the opportunity to think and plan before a crisis arises.

An approach to this sensitive topic might frame it in the following manner: “We are hoping for the best of all possible outcomes; however, it is also helpful to prepare for the worst, to ensure that no matter what happens we are taking the best possible care of your child. [pause, listen, allow for reflection]. We would like to decide together whether your child should undergo cardiopulmonary resuscitative efforts if we believe she or he has an irreversible problem.” This approach along with reassurance that a life-threatening event is not imminent enables parents to maintain hope while facing this decision. It is also helpful to reassure parents that if the child’s condition should improve, the decision would be reconsidered. Even if a family is initially unable to make a decision about resuscitation status, it is helpful for them to have heard that they may have to face this decision in the future.

Careful thought should be given to the exact words used during a discussion regarding resuscitation status. Parents often think that agreeing not to resuscitate is choosing death over life for their child. It is helpful to explain that it is the uncontrolled cancer that would cause the death. To some parents, the phrase “do not resuscitate” implies that if these interventions were performed, they would be successful. Experience tells us that among children with advanced cancer, the likelihood of a patient being extubated and leaving the hospital is very low. Thus, when approaching families about this issue, it is preferred to use the phrase “do not attempt resuscitation (DNAR).” several institutions use a more affirmative term, “Allow

Natural Death (AND).” Some suggest that this phrase is softer and more comforting and implies that the team will continue caring for the family member,35 but it may also be more ambiguous.36 Regardless of the terminology, it is important to reinforce what will be done to continue to care for their child, such as attending to their comfort. In addition, it is important for clinicians to not assume that a DNAR order in place indicates that care other than resuscitative measures in the setting of cardiopulmonary arrest has also changed.37

Natural Death (AND).” Some suggest that this phrase is softer and more comforting and implies that the team will continue caring for the family member,35 but it may also be more ambiguous.36 Regardless of the terminology, it is important to reinforce what will be done to continue to care for their child, such as attending to their comfort. In addition, it is important for clinicians to not assume that a DNAR order in place indicates that care other than resuscitative measures in the setting of cardiopulmonary arrest has also changed.37

Documentation should always specify under which circumstances a DNAR order is applicable. In the outpatient setting, it is helpful to provide the family with a letter to keep with them at all times, that briefly summarizes the patient’s medical condition and documents the details of the resuscitation status discussion. In several states, there is also an official DNAR verification form, which permits emergency medical teams to honor DNAR orders written in the hospital or clinic. An increasing number of states have adopted Physician Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment (POLST), medical orders communicating patient preferences regarding resuscitation efforts and life-sustaining treatment across care settings. Emerging evidence from the adult population indicates that adults who wished to avoid hospitalization, as documented in POLST, were less likely to die in the hospital.38

Location of Care

Studies have found that slightly more than one-half of children with progressive cancer die at home.39,40,41 With regard to preferred location of care, one retrospective study found that 70% of bereaved parents ranked home over hospital or freestanding hospice as their choice location for the death of their child.42 Although many have suggested that most children prefer to die at home, this, too, has not been systematically evaluated. Creating the opportunity for dying at home may be dependent on the availability of services as well as the clinical context. Options may also be influenced by the cause of death and whether death was anticipated (e.g., relapse vs. treatment-related complications).43 For example, children who died following hematopoietic stem cell transplant as their last cancer-directed therapy were less likely to die in the family’s preferred location, compared with other children who died from cancer.44

More important than actual location is giving parents the opportunity to plan a child’s location of care and death. It is critically important to discuss preferences and options regarding the preferred location of death as early as possible. Dussel et al.45 found that parents who had the opportunity to plan were more likely to choose home as the primary location and that they experienced less regret about their decision on the location of care. Location options include inpatient care or home care with or without the support of a home care team. Increasing numbers of hospitals are developing palliative care services, and preliminary data suggest that concurrent with the integration of a palliative care service key end-of-life outcomes are improved. Specifically, parents report diminished child suffering from pain and other prevalent symptoms and an improved sense of preparation for the child’s end-of-life course.40 While there are very few inpatient pediatric hospice units, one innovative intervention is the development of hospital-based homelike suites to allow for inpatient care of the child in an environment that accommodates the entire family.46 Whatever the decision regarding the primary location of care, families should be reassured that they can change from one option to another and that the primary team will remain closely involved.

Home-based Care and Support. A parental decision to care for their child at home involves the consideration of medical, psychological, social, and cultural factors together with such practical considerations as the availability of home care support, respite care, physician access, and financial resources. Home care teams might include a visiting nurse association, bridge programs, or hospice. About a third of all hospices provide pediatric care47 and there are very few inpatient pediatric hospice units.

Provision of home care for children with advanced illness presents some challenges. Experience demonstrates that pediatric-specific programs often face financial difficulties, though a recent analysis found that possessing pediatric experience does not add to core hospice care costs.48 Experience demonstrates, however, that it may be challenging for hospices to find staff experienced in addressing the unique medical and psychological needs of children. Finally, with regard to hospice, parents may be reluctant to accept hospice support as they equate it with “giving up.”

When families are able to embrace hospice, assistance from these programs can be invaluable. Interdisciplinary hospice teams may include a nurse, physician, and home health aide as well as a social worker, chaplain, and volunteers. Optimal hospice care for children incorporates physical care for the child, home care, pain and symptom management, psychosocial support for child and family, respite care, staff support for health care providers, and special services such as transportation. Importantly, hospice programs are required to provide bereavement follow-up for family members.

It is important to understand that currently, for a child to be eligible for hospice, the physician must consider the child’s life span to be no longer than 6 months. Furthermore, reimbursement mechanisms for hospice differ from typical home care. Specifically, the Medicare Hospice Benefit provides a per diem reimbursement for care.49 Because children often receive disease-directed treatments until the very end of life, this has historically precluded them from enrolling in hospice. Continued cancer-directed therapy and uncertain prognosis have been some of the most common reasons for lack of child referral to hospice. However, the Concurrent Care Requirement, implemented in 2010 under the Affordable Care Act, was designed to address this barrier by allowing children covered by Medicaid to receive concurrent hospice care and treatment for their underlying illness. Unfortunately, it did not remove the 6-month prognosis requirement. Some states have pursued other initiatives to expand access to palliative care services, including state Medicaid plan amendments or waivers to allow children to enroll on hospice even if they do not meet the 6-month prognosis requirement50 and, in the case of Massachusetts, a state-funded pediatric palliative care program.51

Autopsy

When a child dies from progressive cancer, it may seem that there is no reason to perform an autopsy. However, postmortem examinations may provide a great deal of additional information. Sirkia et al. found that in 40 children who died of progressive cancer, autopsy examinations afforded new information in 20% of cases and important additional information in 55%.52 Regardless of whether new information about their child is uncovered, a recent study revealed that 77% of families valued its contribution to medical knowledge.53 The autopsy also provides an opportunity for families to return for a follow-up discussion, often an important step in bereavement.54 Given the complexities of an autopsy decision, families should be given the opportunity to consider this possibility in advance of the child’s death, whenever possible. Wiener et al.55 found that the majority of bereaved parents feel that autopsy should be introduced when it becomes clear that cure is no longer possible.

Organ Donation

Like autopsy, it is often helpful for families to have had the opportunity to consider organ donation in advance of the child’s death. While some families find the option of organ donation meaningful, the array of factors influencing their decision is complex. Representatives from organ procurement organizations (OPO) are available to speak with families about the possibility of organ donation, which frequently facilitates a decision to pursue organ donation.56 A shared approach in which medical teams and OPO representatives partner to provide families with the support and

information needed when considering this topic may be particularly helpful to families.

information needed when considering this topic may be particularly helpful to families.

Discussing Advanced Illness and Related Issues with Children

One side of my head says: “Think optimistic.” The other side says: “What if this treatment doesn’t work?”

—(11-year-old child)57 p. 156

Many children can face and negotiate discussions about their care to a remarkable degree. An important consideration is the extent to which children should be included in the decision-making process.

Psychologist: Do you remember what we talked about last time? Child (age 5): (without hesitation) About dying…. (A few minutes later) If I don’t feel like talking about dying today, there will be other days.57 (p. 121)

In the past, professionals relied on “normal” (i.e., not seriously ill) children’s developmental understanding of death to judge their involvement. However, these “norms” do not reflect the sophistication of children who face the prospect of death. In general, children with advanced illness may have a precocious understanding of the concepts of death and their personal mortality. A child’s likely developmental understanding of death based on age is helpful when engaging them in conversations about death, recognizing that such understanding is highly variable and it is only through such conversations that an individual’s conceptualization of death can be known.

Most children learn to recognize when something is “dead” before they reach the age of 3 years, but at this early age, death, separation, and sleep are almost synonymous in the child’s mind. As children grow to preschool age, they come to recognize that a dead person cannot function, but they are likely to believe that death is temporary. Their egocentric reasoning makes them vulnerable to believing they can cause death with their thoughts or actions. However, most preschoolers do not understand why people die. School-age children are typically problem solvers, who have begun to develop logical thought. During these years, they normally acquire a much more complete understanding of death, including its irreversibility, universality (i.e., that everyone will die), and that people die from both internal and external causes. They are interested in the specific details of death, and in the latter part of this phase they are able to envision their own deaths. For teenagers, thoughts about death are usually consistent with reality. They are ready to add to their complete definition of death the effect it has on other people and on society as a whole. Their future orientation makes it difficult for them to recognize their own deaths as a present possibility, although they can conceive this occurring at some point in the future.

A 13-year-old girl with widespread disease recounted to the therapist: “I know how to read palms, and I read my own. I’ll be famous. I’ll be married once. I see a break in my life when I’m about seventeen. I wonder what that is….”58 (p. 268)

An 11-year-old girl commented matter-of-factly: “Some of my friends have died. I wish I could talk to those kids’ parents to see what their symptoms were, so that I would know what is happening to me.”57(p. 157)

It is impossible to lie to a child and preserve a relationship that is built on trust and caring. Children will often know when they are dying and may feel tremendous isolation if they are not given permission to talk openly about their illness and impending death.59 Candor is just as crucial in communicating with the siblings, as evidenced in the following drawing and commentary by a 10-year-old child (Fig. 50.6).

In recent years, there has been increased recognition of the child’s participation in making treatment decisions. In a survey of 50 children aged 8 to 17 years with cancer, 95% indicated they would want to be told if they were dying.60 Although most of the children felt that treatment decisions were up to the physicians, 63% of the adolescents and 28% of the younger children wanted to make their own decisions about continued cancer therapy. In general, the approach to decision-making should be tailored to the individual child and family. Crucial to this process is an assessment of the child’s ability to appreciate the nature and consequences of a specific medical decision. This is often a point when input from members of the interdisciplinary team can be crucial: children may express their understanding, awareness, and thoughts about treatment options and living or dying to individuals other than their parents or primary physician (Fig. 50.7).

An 11-year-old child who had been offered radiation therapy for palliative symptom control confided to her therapist: “I’m scared because I’m not so good at making decisions. My parents want me to have radiation, but a little voice in me tells me not to…. My mother always said that if I die, she wants me to die happy and at home. If I had radiation, I’d have to come into the hospital every day. And I don’t know if radiation will really help, or if I would die anyway.” This child had been through many remission-relapse cycles, and had been informed and involved in all aspects of her illness and treatment from the beginning. Nonetheless, her statements highlight the “burden” of decision-making that children may feel at critical junctures of their illness, particularly at end-stage. Furthermore, despite what had been her clear understanding of the reason for radiation therapy (exclusively for palliative symptom management), her intense emotion and hope have overridden the intellectual as she wonders whether the radiation will help her to live longer “or would I die anyway.”1 p.15661

Considerations about what, or how much to tell and individual child centers on their competence and vulnerability and include: the child’s age, cognitive and emotional maturity, family structure and functioning, cultural background, and history of loss. In communication with the life-threatened child at any juncture, “the truth is not a principle nor a duty nor a rule. The truth is an atmosphere of exchange, of listening, and of respect for the child and his needs. The truth is a state” (p.473).62 The precedent for a climate that enables such honest interchange is created from the time of diagnosis. In this way, parents may avoid experiencing regret about not having discussed death with their child, as seen in 27% of parents who felt regret for not having discussed it with their child in one study. It is also important to note that in this study

none of the 147 parents who talked with their child about death regretted it.63

none of the 147 parents who talked with their child about death regretted it.63

Several tools facilitating conversation around end-of-life considerations exist. “Five Wishes” (adults), “Voicing My Choices” (adolescents and young adults), and “My Wishes” (school-age children), are useful for either gently introducing advance care planning to children, adolescents, and their families or guiding such conversations. In some instances, parents appreciate the opportunity to review these tools as a way to learn about the kinds of considerations that might lie ahead, even if the tools are not used as actual conversation guides (www.agingwithdignity.org).

A randomized controlled advance care planning intervention utilizing “Five Wishes” for adolescents with cancer and a parent or surrogate found that the intervention was associated with higher treatment preference congruence.64 Five Wishes is available in 26 languages and for patients >18 years meets the legal requirements for an advance directive. Though not a legal document, “My Wishes” contains opportunities for younger children and a parent or clinician explore these issues at a developmentally appropriate way and for the child to express how they would like to be cared for in case they become seriously ill through artwork and writing. “Voicing My Choices” is similar to “Five Wishes” but is geared for the adolescents and young adults (AYA) population. It allows them to express how they would like to be cared for in the course of their illness, and how they would like to be remembered if they do not survive. AYA with metastatic or recurrent cancer of HIV infection provided input during the development of this tool, revealing it is important for them to have the opportunity to choose and record preferences about their care, information for their family and friends to know and how they would like to be remembered.65 Unlike Five Wishes (under certain conditions), it is not legally binding.

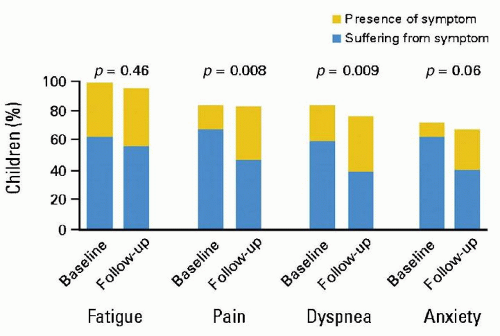

Symptom Management

Children with cancer experience a high prevalence of symptoms during the last month of life, with fatigue, pain, and dyspnea resulting in significant suffering.39 Increased availability of palliative care services, however, is associated with improvement in symptom control (Fig. 50.8).40 Intensive symptom management is a priority in patients with advanced cancer. Symptoms that are out of control should be considered a medical emergency requiring direct evaluation of the patient and immediate implementation of interventions.

Fatigue

Fatigue is one of the most common symptoms experienced by children with advanced cancer.39,66 Cancer-related fatigue is unlike everyday fatigue in its impact on everyday activities and lack of responsiveness to rest. Children are apt to describe fatigue in physical terms, while adolescents may articulate both physical and mental aspects of this symptom. Cancer-related fatigue is often multifactorial in etiology, often due to the underlying disease; treatment of the disease; medication side effects, anemia, infection, malnutrition, compromised organ function; sleep disturbance; and uncontrolled symptoms.67,68 Thus, treatment of fatigue requires careful evaluation of the child aimed at identifying treatable underlying causes. In some situations, such as fatigue primarily related

to advanced disease or organ failure, expectations for reversal of the symptom are limited. This should be explained to the patient and parents as a part of a plan to improve adaptation. However, some primary interventions may be helpful. For example, the drug therapies administered to the patient should be reviewed whenever fatigue is prominent with specific attention to centrally acting drugs. Increasingly, methylphenidate or dextroamphetamine is recommended for symptomatic relief of fatigue, regardless of the suspected etiology.69 The threshold for intervening to address insomnia,67,70 some metabolic abnormalities, or depressed mood should be low. Exercise is effective in relieving fatigue in adults with cancer. Moderate physical activity as tolerated may also be efficacious for children, even near the end of life.

to advanced disease or organ failure, expectations for reversal of the symptom are limited. This should be explained to the patient and parents as a part of a plan to improve adaptation. However, some primary interventions may be helpful. For example, the drug therapies administered to the patient should be reviewed whenever fatigue is prominent with specific attention to centrally acting drugs. Increasingly, methylphenidate or dextroamphetamine is recommended for symptomatic relief of fatigue, regardless of the suspected etiology.69 The threshold for intervening to address insomnia,67,70 some metabolic abnormalities, or depressed mood should be low. Exercise is effective in relieving fatigue in adults with cancer. Moderate physical activity as tolerated may also be efficacious for children, even near the end of life.