31332

Palliation of Nonpain Symptoms

Katherine Wang and Emily Chai

INTRODUCTION

A geriatric patient with cancer may experience symptoms—attributable to malignancy itself or to side effects of treatment—that significantly impact quality of life. Palliative care places priority on eliciting symptoms and offering relief with treatments in line with the patient’s overall goals. This chapter addresses some of the most common cancer- and treatment-related symptoms including fatigue, anorexia, constipation, nausea and vomiting, and wound odor.

Symptom management is challenging in the older oncology patient. First, symptomatology associated with preexisting comorbidities increases the complexity of managing cancer- and treatment-related symptoms. Cognitive impairment or acute delirium may also adversely impact a patient’s ability to reliably report symptoms. Finally, both polypharmacy and age-related alterations in pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics complicate the selection and titration of medications for symptom relief (1).

Adhering to the following core principles of geriatrics will ensure safe and effective management of older oncology patients:

1. Incorporate functional assessment into routine practice. Functional ability is both a key indicator of overall health and an important patient-centered outcome, and can help guide selection of appropriate treatments.

2. Be aware that iatrogenesis, or the unintended effects of medical therapies, is common and often preventable.

3. Start at lower doses when considering medications for symptom relief. Be alert for the potential need to escalate rapidly, depending on the response.

4. Integrate the patient’s goals, values, and priorities into decisions about treatment options. Recognize that the risks and benefits of treatment in a geriatric patient may differ from those in a younger patient.

5. Use validated symptom assessment tools such as the Edmonton Symptom Assessment Scale (ESAS) and the Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale (MSAS) to screen for and track symptoms over time (2,3).

314FATIGUE

Cancer-related fatigue, present in up to 90% of cancer patients, is common, disabling, undertreated, and inversely related with quality of life (4,5). The National Comprehensive Cancer Network defines cancer-related fatigue as a “distressing, persistent, subjective sense of physical, emotional, and/or cognitive tiredness or exhaustion related to cancer or cancer treatment that is not proportional to recent activity and that significantly interferes with usual functioning” (6).

The pathophysiology of cancer-related fatigue is poorly understood but may relate to proinflammatory cytokines, dysfunction of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis, or serotonin dysregulation (7,8). Fatigue in geriatric cancer patients may be multifactorial: (a) primary fatigue that is due to the cancer and/or therapy or (b) secondary fatigue that is linked to concurrent syndromes or illnesses (e.g., anemia, fever), medications, insomnia, or depression.

Assessment

Clinicians should screen for fatigue using single-item scale (e.g., “I get tired for no reason”) or other tools such as the ESAS, Functional Assessment for Chronic Illness Therapy Fatigue (FACIT-Fatigue), or Brief Fatigue Inventory (9–12). A single-item scale is rapid and validated, but we recommend the ESAS for longitudinal symptom assessment. A thorough workup of secondary causes of fatigue includes labs such as complete blood count (CBC)/iron studies, thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH), basic chemistry, hepatic function panel, and vitamin B12 levels.

Treatment

Consider treating secondary causes of fatigue if consistent with patient’s goals. This might include erythropoietin or transfusion for anemia, antidepressants for mood disorders, reducing or rotating medications in the case of polypharmacy, or hormone substitution in the case of hypothyroidism or hypogonadism.

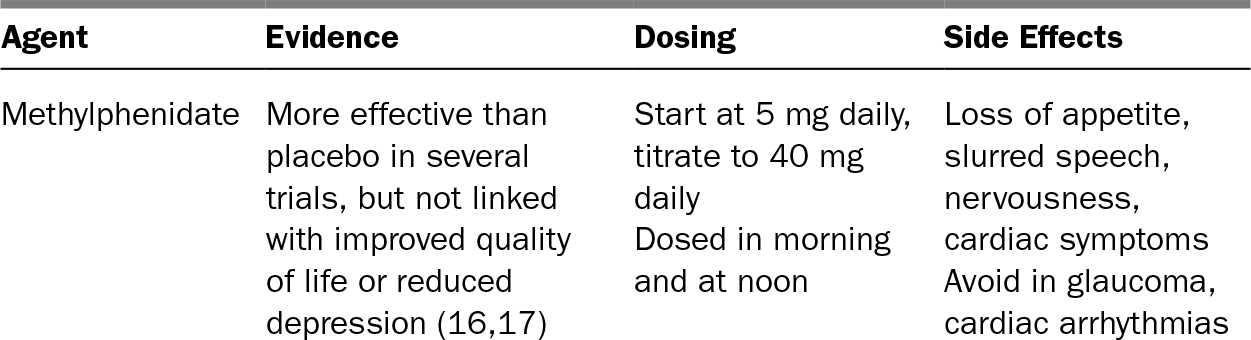

If the aforementioned strategy involves therapies deemed too burdensome for the patient, then focus on treating the symptoms of fatigue. Nonpharmacologic strategies to reduce symptoms of fatigue include education and expectation-setting, exercise, and therapy (cognitive behavioral therapy, individual or group psychotherapy) (13,14). Acupuncture may have some benefit (15). Pharmacologic therapies that have mixed data to support their use are listed in Table 32.1.

TABLE 32.1 Pharmacologic Therapy for Cancer-Related Fatigue

315

ANOREXIA AND CACHEXIA

Anorexia (the loss of appetite) and cachexia (involuntary weight loss associated with decreased muscle mass and adipose tissue) are reported in up to 80% of patients with cancer and cause significant distress for patients and their families (20). Due in part to the hypermetabolic and hypercatabolic state of malignancy, cancer cachexia is a complex syndrome with variable diagnostic criteria that is not fully understood or easily treatable. It often signals advancement of the underlying malignancy and portends a poor prognosis (21,22). Older adults are particularly at risk for anorexia given the higher likelihood of polypharmacy, chronic comorbidities (e.g., chronic kidney disease [CKD], heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [COPD]), and age-related changes in taste and smell that may reduce appetite.

Assessment

Clinicians must consider secondary causes of impaired food intake such as nausea, vomiting, constipation, xerostomia, mucositis, candidiasis, hypothyroidism, or hyperthyroidism. Thorough workup should include depression screening and labs such as TSH.

Treatment

If anorexia and cachexia are the result of advanced underlying malignancy, then no therapies have been shown to extend life. Adjusting expectations and providing 316education will reinforce for patients and families the significance of these symptoms as indicative of the severity of underlying illness. Nonpharmacologic therapies should be encouraged, such as offering favorite foods via small, frequent meals, giving assistance with eating if needed, and reducing polypharmacy.

Pharmacologic therapy has limited proven benefit (18). The two most extensively studied treatments—progestins and corticosteroids—are shown to improve appetite and weight but not to extend life. There is also limited benefit for long-term quality of life (23). If a trial is desired, megestrol acetate is given at the lowest starting dose (160 mg daily). Side effects include edema and increased thromboembolic risk. Of corticosteroids, dexamethasone 2–20 mg daily or prednisone 20–40 mg daily have been studied; given short-lived benefit and high toxicity, we do not recommend steroids if life expectancy is on the order of months to years. Dronabinol and other synthetic cannabinoids, while helpful in stimulating appetite in patients with AIDS, have not demonstrated benefit for cancer-related anorexia and cachexia and are not routinely recommended (24).

CONSTIPATION

Constipation is a common, frustrating complaint among older adults; cancer and related therapies (notably, opioids) increase the likelihood of developing constipation. A cascade of secondary symptoms may result, including anorexia, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, delirium, urinary retention or incontinence, and overflow fecal incontinence. The definition of constipation may include decreased frequency or symptoms such as straining, requiring self-disimpaction, or incomplete evacuation.

Assessment

Clinicians should evaluate for reversible secondary causes of constipation: dehydration, decreased dietary fiber, or medications. Consider eliminating common medications that may cause constipation such as antacids, anticholinergics, antidepressants (especially tricyclics), antihistamines, beta-blockers and calcium channel blockers, calcium supplements, diuretics, iron, levodopa, ondansetron, and opioids. Pay particular attention to bowel sounds on abdominal exam. Rectal exam will allow the clinician to assess for fecal impaction, masses, strictures, or rectoceles. If there is concern for bowel obstruction, consider abdominal plain film. Lab work may include CBC, electrolytes, calcium, phosphorus, magnesium, and TSH.

Treatment

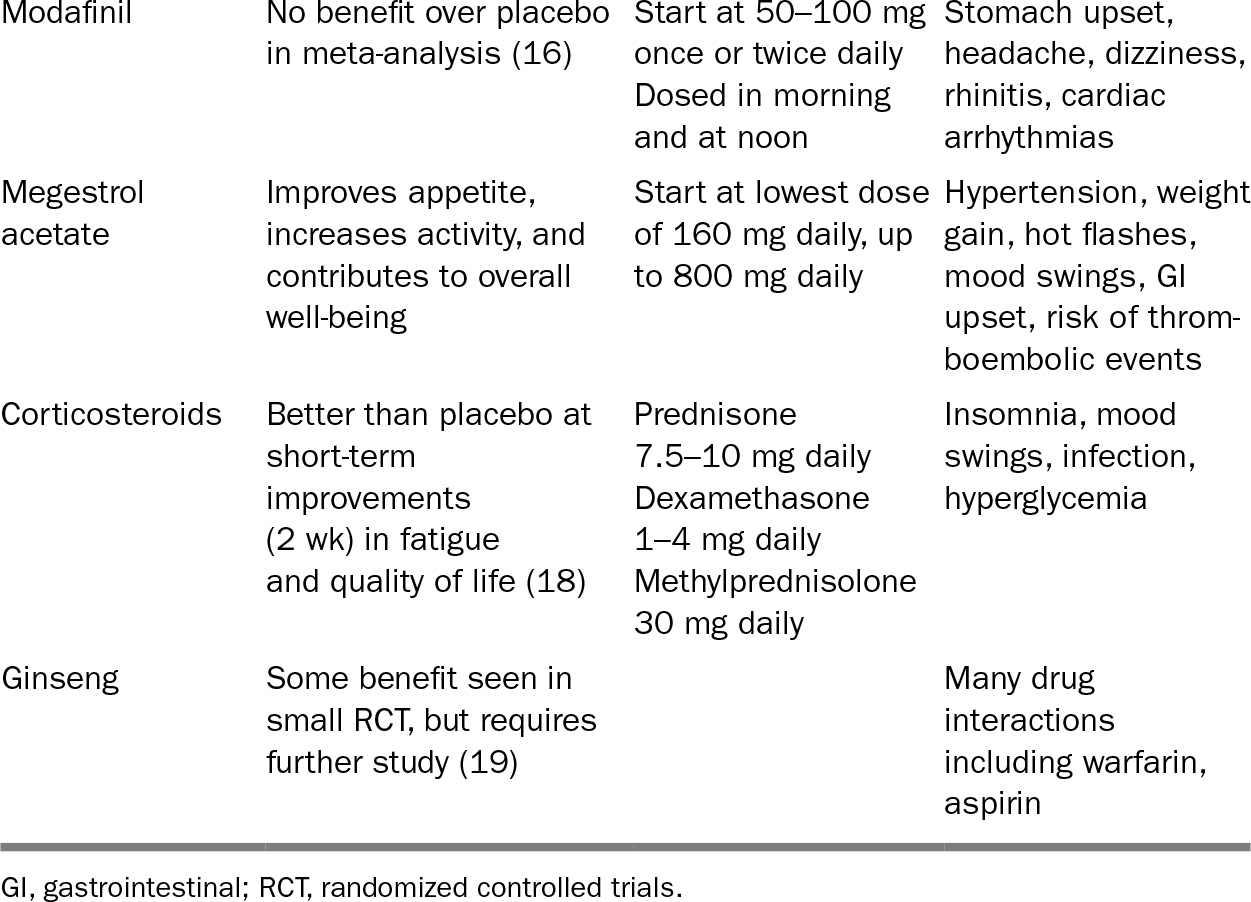

Selection of pharmacologic agents depends on side effect profile, route of delivery, and patient preference; there are no widely accepted evidence-based guidelines for the treatment of constipation (25). However, in particular for patients on chronic opiates, a daily bowel regimen is essential for preventing constipation. Table 32.2 outlines various oral and rectal options (27). Dosing does not need to be adjusted for geriatric patients. Fiber and bulk-forming laxatives (e.g., psyllium) should only be used if the patient is mobile and has adequate water intake. There is limited evidence for nonpharmacologic therapies such as massage, exercise, or biofeedback in the management of constipation.

317TABLE 32.2 Pharmacologic Therapy for Constipation

318NAUSEA AND VOMITING

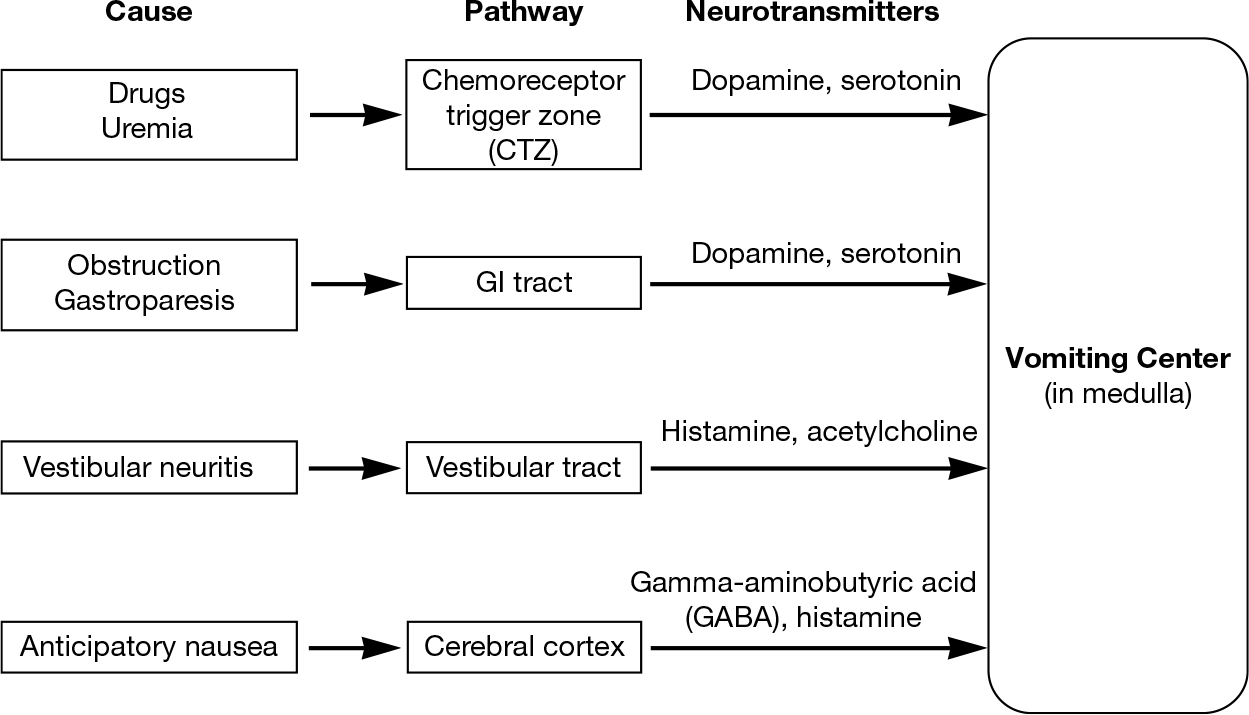

Nausea and vomiting are common and distressing complaints for older adults with cancer that may lead to anorexia, weight loss, dehydration, and electrolyte abnormalities. Nausea and vomiting may exist in the context of chemotherapy (iatrogenic due to treatment itself or due to anticipatory nausea), or as a result of malignancy itself. Uremia, gastroparesis, metabolic disorders, increased intracranial pressure, medications, and liver capsular stretch are also known to cause nausea and vomiting. The vomiting center receives inputs from four sites, each with associated neurotransmitters (see Figure 32.1) (28). Rational and effective therapy thus depends on identifying the etiology of the vomiting and targeting the appropriate neurotransmitters.

Assessment

A thorough history (duration, frequency, severity, and timing) and exam (for sequelae that should be treated, such as dehydration, or for potentially treatable etiologies, such as gastroparesis or obstruction) are essential. Imaging and procedures may be helpful to assess for or rule out conditions such as obstruction, gastric outlet obstruction, or peptic ulcer.

Treatment

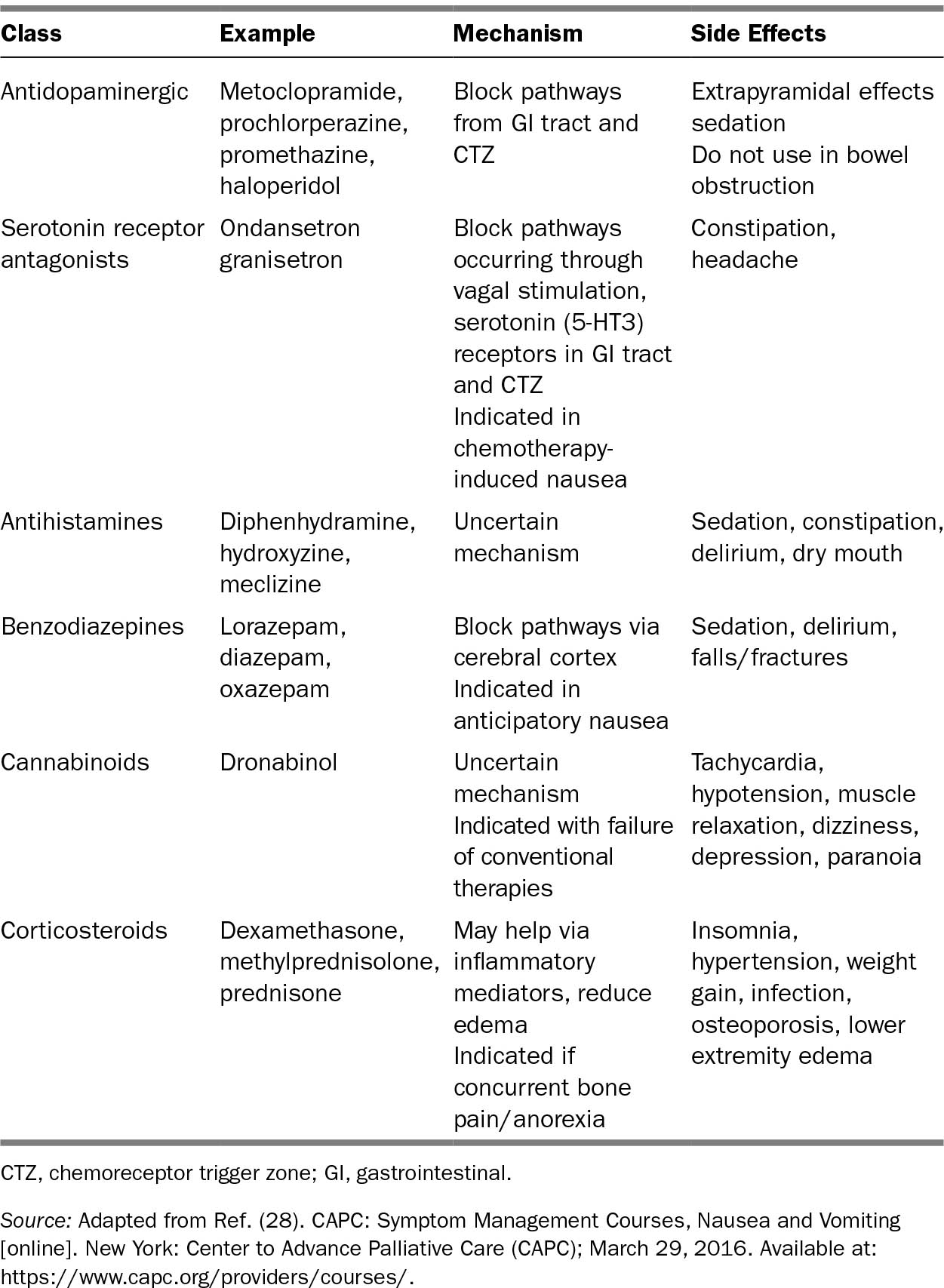

The etiology of nausea and vomiting is often multifactorial and therefore may require a combination of agents for control. See Table 32.3 for recommended pharmacologic therapy, based on presumed etiology. We recommend against the use of scopolamine patch in geriatric patients given the high potential for delirium due to anticholinergic effect. Adjunctive nonpharmacologic therapy might include acupuncture (particular benefit has been seen postoperatively and after chemotherapy) and relaxation/meditation.

FIGURE 32.1 Neurotransmitters implicated in emetogenic pathways.

319TABLE 32.3 Pharmacologic Therapy for Nausea and Vomiting

WOUND ODOR

Malignant wounds occur when cancerous cells (from a primary lesion or metastasis to the skin) invade the epithelium, thereby interrupting vascularity and causing necrosis to the area. Bacteria colonizing these lesions are prone to releasing odor, causing distress for patients and caregivers and leading to embarrassment, stigma, and social isolation.

320Assessment

Evaluate for signs of infection such as pain, purulence, erythema, or surrounding warmth. These findings are not necessarily diagnostic of acute infection and need to be evaluated within the particular clinical context. Similarly, odor may result from byproducts of anaerobic and gram-negative organisms simply colonizing the wound (29).

Treatment

Malignant wounds may not be curable; therefore, treatment options are guided by patients’ goals. If appropriate, palliative radiation therapy may be considered; if there is concern for active infection, then systemic treatment may be initiated (e.g., metronidazole 500 mg PO or IV 3–4 times daily). Often, however, palliative treatment involves managing the wound bed and odor with local therapy. Some evidence-based strategies are listed in Table 32.4 (30).

TABLE 32.4 Strategies for Managing Malignant Wounds

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree