INTRODUCTION

Cancer is frequently associated with a host of distressing physical and psychosocial symptoms that can occur throughout the disease trajectory (1). Access to a multidisciplinary supportive care service is imperative for patients with cancer experiencing distressing symptoms, including fatigue, pain, anorexia, nausea, dyspnea, anxiety, depression, and weight loss, to improve the quality of life of patients. Without optimal symptom control, administration of anticancer therapies may be delayed or discontinued (Table 58-1).

CANCER PAIN

Uncontrolled pain has been reported by 42% of patients seen in the outpatient cancer center (1) and 50% of hospitalized patients with cancer (2). Pain was the most common symptom (82%) among patients with cancer referred to a palliative care service (3). In patients with cancer, pain may be the only symptom present prior to diagnosis and can indicate the recurrence or spread of the disease.

As many as 30% to 50% of patients receiving active anticancer therapy experience pain (1). Pain resulting from the tumor burden occurs in approximately 65% to 85% of patients with advanced cancer (4). In addition, treatment-related pain is reported by approximately 15% to 25% of patients, and 3%-10% of patients with cancer develop chronic nonmalignant pain syndromes similar to the general population (eg, low back pain associated with degenerative disk disease).

The pathophysiologic classification of pain forms the basis for therapeutic choices. Pain may be broadly divided into those associated with ongoing tissue damage (nociceptive) and those resulting from nervous system dysfunction (neuropathic). Nociceptive pain can be classified as either somatic or visceral and results from the activation of nociceptors in cutaneous or deep tissues. Nociceptive pain is described by patients as localized aching, throbbing, and gnawing discomfort. Visceral pain is the result of activation of nociceptors resulting from distention, stretching, and inflammation of internal organs. It is often poorly localized discomfort, described as a deep aching or cramping or a pressure-like sensation. An example of visceral pain is abdominal pain due to pancreatic cancer. Breakthrough pain is defined as a transitory exacerbation of discomfort that occurs on a background of stable persistent chronic pain. Causes of breakthrough pain include end-of-dose failure of opioids and pain exacerbation by activity or spontaneous occurrence. Breakthrough pain is also characterized by a short duration, often less than 3 minutes in 43% of cases according to previous prospective surveys (5).

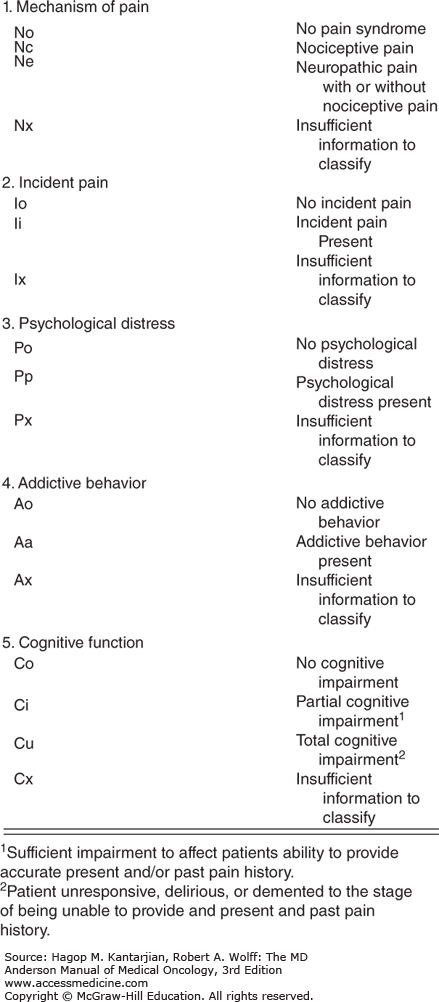

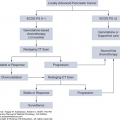

Classification of pain can help guide selection of appropriate interventions to improve pain control; however, they have not been universally accepted. Pain mechanism, incidental occurrences, psychological distress, addictive behavior, and cognitive dysfunction have been indicated as factors associated with higher ratings of pain intensity (6). The revised Edmonton Classification System for Cancer Pain (Fig. 58-1) characterizing these factors has been used at our institution to guide pain management.

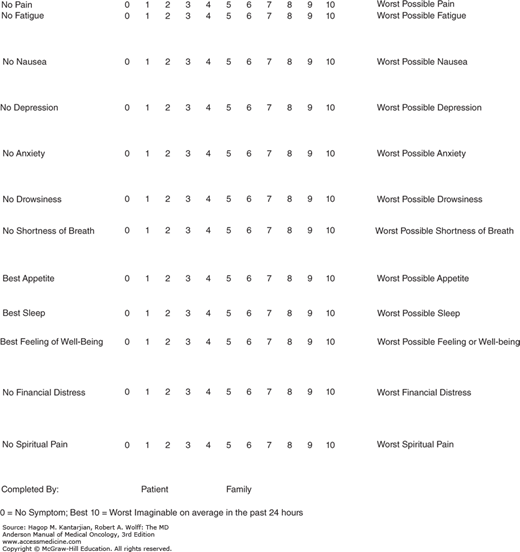

Pain can be measured by using visual, analogue, verbal, or numerical scales and, in the research setting, complex pain questionnaires (7). The Edmonton Symptom Assessment Scale is a useful assessment tool that allows patients to rate pain between 0 and 10 over the past 24 hours, where 0 signifies no pain and 10 is the worst pain imaginable. Effective pain assessments can be converted into graphic displays of pain and incorporated with other symptoms, allowing quick dissemination of information regarding a patient’s symptom burden to all health-care providers (Fig. 58-2). Pain assessment needs to take into account other symptoms experienced by patients with cancer because they are often are interconnected.

In 1984, the World Health Organization (WHO) proposed an analgesic ladder for the pharmacologic management of cancer pain (8) and has shown that the simple principle of escalating from nonopioid to strong opioid analgesics is safe and effective (Fig. 58-3). Other guidelines have been published, such as the Analgesic Quantification Algorithm and National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines for treating cancer pain (9).

Assess pain syndromes and other symptoms accurately.

Respect and accept the complaint of pain as real.

Treat pain appropriately.

Treat underlying disorders.

Address psychosocial concerns.

Multidisciplinary approach is essential.

PHARMACOTHERAPY

Match the drug to the pain syndrome.

Low threshold to prescribe opioids for cancer pain.

Use sustained-release formulations for constant, chronic pain and short acting for breakthrough discomfort.

Use adjunct medications for certain pain syndromes.

Use an oral route for analgesics if possible.

Use an intravenous route for acute titration.

Sequential opioid trials are often beneficial.

Become familiarized with equianalgesic dosing.

Become familiarized with the pharmacokinetics of opioids.

Differentiate between tolerance, physical dependence, and addiction.

Use caution with opioid and adjuvant drug titration in the setting of renal impairment.

A bowel regimen should always be prescribed with an opioid prescription because of the constipation opioids induce.

Always include stimulant laxatives to prevent opioid-induced constipation.

Preferred choices include sennosides and polyethylene glycol.

Decreased motility, gastroparesis, is a common side effect of opioids and can be treated with metoclopramide.

Activity and adequate hydration are important.

Bulking agents without a prokinetic may worsen constipation.

Refractory constipation may be managed with lactulose 30 mL by mouth every 6 h until a large bowel movement occurs.

Intractable cases may require a suppository or enema.

Proximal impaction may require oral laxatives.

In rare cases of hard stools present in the vault, manual disimpaction may be necessary.

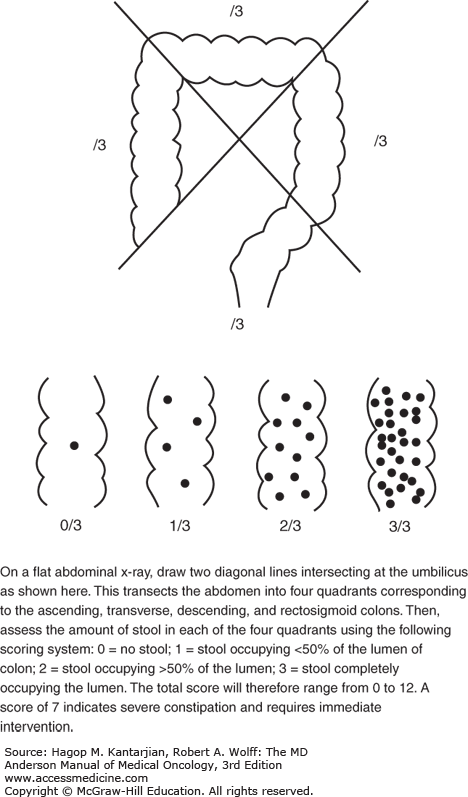

Constipation may be evaluated with imaging to assess the degree of severity of constipation (Fig. 58-4).

Opioid rotation is the switching from one type of opioid to another in the setting of opioid neurotoxicity. The following are reasons to rotate opioids:

Uncontrolled pain despite escalating opioid doses

Development of tolerance or dose-limiting side effects of opioid neurotoxicity (hallucinations, confusion, myoclonus)

Hyperalgesia as a result of the production of excitatory amino acids from the opioid itself

Cost necessitating switching of opioid

Opioid rotation has been shown to not only improve pain control, resolve delirium, and alleviate myoclonus, but also may improve other symptoms, including depression and insomnia (10).

In a recent study of an outpatient population of 114 patients with cancer at MD Anderson Cancer Center with mean Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status of 1, opioid rotation for side effects or uncontrolled pain achieved improved symptom control successfully in 65% of the patient population (10).

Individual variability of opioid activation of multiple subtypes of opioid receptors accounts for the benefits of opioid rotation that should be considered when managing uncontrolled pain (11,12). In difficult cases, this may include rotation on two or three occasions to reduce opioid neurotoxicity and improve pain control.

The following are general guidelines for opioid rotation:

Calculate total daily dose.

Calculate dose of new opioid using opioid conversion table (Tables 58-2 and 58-3).

Reduce dose of new opioid by 30% to 50% to account for incomplete cross tolerance.

| Drug | Usual Starting Dosages |

|---|---|

| Full opioid agonists | |

| Morphinea | 15-30 mg by mouth every 3-4 h |

| Morphine extended release (MScontin) | 30-60 mg by mouth every 8-12 h |

| Hydromorphone (Dilaudid) | 2-4 mg by mouth every 4-6 h |

| Hydromorphone ER (Exalgo) | 8-16 mg by mouth every 12-24 h |

| Fentanyl (Duragesic) | 25-50 μg/h transdermally every 3 days |

| Codeine | 15-30 mg by mouth every 3-4 h |

| Oxycodone (Percodan and others) | 5-10 mg by mouth every 3-4 h |

| Methadone hydrochloride (Dolophine)b | 5-10 mg by mouth every 3-4 h |

| Partial agonists and mixed agonists/antagonistsc | |

| Nalbuphine (Nubain) | 10 mg IV every 3-4 h |

| Butorphanol (Stadol) | 0.5-2 mg IV every 3-4 h 1-2 mg SL three times a day |

| Dezoncine (Dalgan) | 10 mg IV every 3-4 h |

| Pentazocine (Talwin) | 50 mg by mouth every 4-6 h |

| Intravenous MO | Oral MO | 1:2.5 |

| Intravenous HM | Oral HM | 1:2 |

| Oral HM | Oral MO | 1:5 |

| Intravenous HM | Intravenous MO | 1:5 |

| Oral oxymorphone | Oral MO | 1:3 |

| Oral oxycodone | Oral MO | 1:1.5 |

| Oral HCD | Oral MO | 1:1 at ≥40 mg HCD/d |

| Oral HCD | Oral MO | 1:1.5 at <40 mg HCD/d |

| Fentanyl patch | Oral MO | Fentanyl patch × 2 = Oral MO |

| Intravenous fentanyl | Intravenous MO | 1:100 |

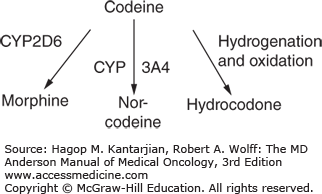

Codeine is a prodrug used to treat mild-to-moderate pain, diarrhea, and intractable coughing spells. It is the second most common alkaloid in opium and is hypothesized to be 200 times less potent than morphine. Metabolism by the liver converts 90% of the drug to inactive metabolites and 10% as morphine. The cytochrome oxidase 2D6 (CYP2D6) gene is responsible for the conversion to morphine and, in some groups, may not be fully active, while others may express multiple copies of the gene and be considered ultrarapid metabolizers (13). These ultrarapid metabolizers have greater risk of opioid neurotoxicity due to codeine rapidly metabolizing into morphine, especially in the pediatric population. On the other hand, patients who have decreased metabolization may experience ineffective analgesia with the drug.

In addition, some medications are CYP2D6 inhibitors and block conversion of codeine to morphine when coadministered. These include the antidepressants paroxetine, fluoxetine, buproprion, and diphenhydramine. Medications known to increase CYP2D6, such as dexamethasone, should also be used with caution with codeine (Fig. 58-5).

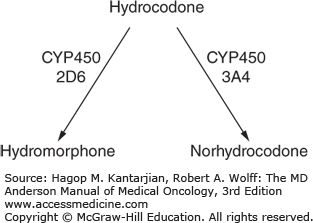

Hydrocodone has historically been considered a weak opioid on the WHO ladder. It is manufactured commonly in combination with acetaminophen or ibuprofen. It is a semisynthetic opioid derived from codeine and is metabolized by the liver and excreted in the urine. Hydrocodone is metabolized by cytochrome P450 2D6 to hydromorphone. Recent studies have shown that hydrocodone, when taken at doses of less than 40 mg per day, is equivalent to one and half the strength of morphine; however, the ratio of morphine to hydrocodone at doses greater than or equal to 40 mg per day have been shown to be closer to 1:1 (14) (Fig. 58-6).

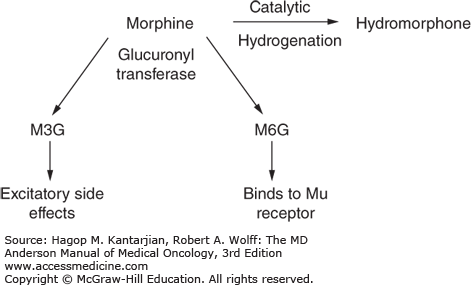

Morphine is commonly used as a standard prototype drug for opioid pain management. It is a naturally occurring opioid purified from opium poppy seeds and is available in short- and long-acting preparations. In the liver, it is converted to morphine-3-glucoronide and morphine-6-glucoronide (M3G and M6G, respectively) by glucuronyl transferase. Morphine-3-glucoronide is responsible for excitatory neurotoxic side effects, including myoclonus, hallucinations, seizures, and confusion and accumulates with renal insufficiency. Morphine is available as oral, rectal, intramuscular, intravenous, and sublingual preparations (Fig. 58-7).

Hydromorphone is a semisynthetic opioid derived from morphine and is five to seven times more potent. It is available for administration via all routes, including neuroaxial. It may be an alternative to morphine when dose-limiting side effects require rotation to a more potent opioid. Long-acting formulations are available, known by the trade name Exalgo, but are expensive.

Oxycodone is another semisynthetic opioid derived from thebaine, a minor natural component of opium similar to morphine and codeine. Oxycodone has been known to be 1.5 times more potent than morphine. Previously, its dosage was limited by its combination with acetaminophen or aspirin, but now it is commonly available as oxycodone by itself as a pill in the United States. It has a higher bioavailability than morphine and exists both as extended-release and short-acting formulations.

Oxymorphone is produced after the CYP2D6 metabolism of oxycodone. It is a semisynthetic opioid and, like oxycodone, is also derived from thebaine. It has a low bioavailability orally and is three times more potent than morphine. Its maximum serum concentration is reached in 30 minutes, and the effects of immediate-release tablets may last up to 6 to 8 hours. Extended-release oxymorphone effects last 12 hours, and it should be dosed as such due to its long half-life of 14 hours. Oxymorphone should be given on an empty stomach because coadministration with food can result in increased absorption and result in opioid toxicities.

Meperidine (Demerol) is a weaker opioid with a potency 1/10 that of morphine. Dose escalation is limited by the risk of accumulation of the metabolite nor-meperidine, metabolized by the liver. Both meperidine and nor-meperidine cause central nervous system toxicity, including convulsions, especially in renal impairment and in the geriatric population. Due these risks, it is becoming less commonly used.

Fentanyl is a synthetic opioid that is 80 to 100 times more potent than morphine and has a rapid onset and short duration of analgesia. It is used often in the setting of acute or incidental breakthrough pain. Transdermal sustained-release formulations, fentanyl patches, are a good choice for stable pain and are changed every 72 hours. Fentanyl patches are convenient in patients with oral routes that are limited or unavailable. Oral transmucosal fentanyl has been used for breakthrough pain; however, fentanyl has a very rapid onset of action, which makes it difficult to calculate total dose delivered, and erratic equianalgesic dosing often raises safety concerns.

Methadone is a synthetic opioid. Recent research (15) has characterized appropriate equianalgesic dosing (16,17), and advantages include low cost, less-active metabolites, good bioavailability, and N-methyl-D-aspartate antagonism, which may account for the absence of the development of tolerance associated with chronic use. Methadone potency can be 10 to 15 times that of morphine; thus, caution should be exercised when rotating to methadone. Close monitoring when initiated is necessary due to its tendency to accumulate as time advances before reaching a steady state. The half-life varies with the individuals; it can be between 15 and 190 hours. Clinicians prescribing methadone should be aware of potential drug interactions due to metabolism via the cytochrome P450 system, with these drugs including antifungals, antiretrovirals, and selective serotonin inhibitors (18). Methadone also has been associated with QTc interval prolongation (19,20), so proper cardiac monitoring is indicated. Prospective studies at MD Anderson Cancer Center found it to be safe in advanced cancer (21). It is being researched as a viable first-line treatment option for pain management (22) and is especially useful in refractory cancer pain (23).

Although opioids are often first-line analgesics, adjuvant medications are useful for pain control in some settings, such as neuropathic pain. Due to the delay in onset as well as side effects with some drug groups, adjuvant drugs may be best reserved after optimal trials of opioids. Of the tricyclic antidepressants drug class, nortriptyline is felt to be the most efficacious and has less cardiovascular side effects. Tricyclic antidepressants are limited by anticholinergic and sedative side effects. Anticonvulsants are helpful in treating brachial and lumbosacral plexopathies. Side effects and safety limit their wide use. For the adjuvant treatment of neuropathic pain, gabapentin has been shown to be effective but does require dose adjustment in renal failure. Pregabalin has been used as an alternative to gabapentin but is costly and has not shown greater efficacy (Table 58-4).

| Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs |

Acetaminophen Aspirin Ibuprofen Naproxen Celecoxib Ketorolac Diclofenac |

Tricyclic antidepressants |

Amitriptyline Nortriptyline Doxepin |

| Antiepileptic drugs |

Gabapentin Topiramate Levetiracetam Tiagabine Oxcarbazepine Lamotrigine Felbamate |

| Local anesthetics |

Lidocaine |

| N-Methyl-D-aspartate receptor antagonists |

Ketamine Methadone Dextromethorphan Haldol |

| Topical analgesics |

Capsaicin Lidocaine patches |

Adjuvant nonpharmacological treatments include nerve blocks, neurosurgical procedures, and radiation therapy. Physical and psychological interventions to treat pain include counseling, psychotherapy, relaxation techniques, massage therapy, music therapy, and acupuncture. Addressing psychosocial and spiritual distress for both patients and family may be needed for patients with cancer experiencing complex, total pain at the end of life (Table 58-5).

|

|