Overview of Endometrial Carcinoma

Anna Sienko MD

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Endometrial carcinoma ranks as the fourth most common malignancy in women, accounting for 6% of female cancers. Endometrial carcinoma is the most common malignancy in women in developed and industrialized countries, with 75% of cases occurring in postmenopausal women at an average age of 61 years1 (Table 2-1). The remaining 25% of cases occur in premenopausal women, with 5% of cases reported in women under age 40 years.2 Premenopausal women who develop endometrial carcinoma usually have certain increased risk factors such as obesity, nulliparity, hypertension, anovulatory cycles, and diabetes.3 An estimated 40,100 cases of endometrial adenocarcinoma will be diagnosed annually in the United States, with 7,470 annual reported deaths.1 One in 20 cases of female cancers reported in Europe are endometrial carcinomas.4 It is estimated that 4,500 new cases of uterine cancer will be diagnosed in Canada in 2010, with 790 deaths.5 Worldwide, endometrial adenocarcinoma has been increasing over the last 20 years, and cervical carcinoma has been decreasing.6 More than 90% of endometrial carcinoma cases are sporadic, with approximately 10% of cases associated with hereditary syndromes such as Lynch II syndrome, also known as hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer. This syndrome is an autosomal dominant germ line defect in DNA mismatch repair genes and accounts for 9% of endometrial carcinomas in patients under 50 years of age (see Chapters 7 and 8). Incidence of endometrial carcinoma is higher among White women compared with Asian or Black women. However, the mortality is much higher among Black women, which is thought to be due to presentation at higher stage of disease and less adequate access to health care.1,7

ETIOLOGY AND RISK FACTORS

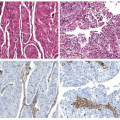

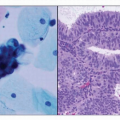

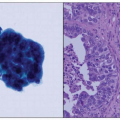

Endometrial adenocarcinoma represents a biologically and histologically diverse group of carcinomas that have traditionally been divided into two groups based on age of presentation, histologic features, and prognosis (Table 2-2). Type I endometrial carcinomas, which account for 80% to 90% of endometrial carcinomas, are seen in perimenopausal women; are estrogen-dependent, well-differentiated tumors (more often endometrioid histology type); and have a favorable prognosis. Type II endometrial carcinomas account for the remaining 10% to 20% of endometrial carcinomas; these carcinomas occur in older postmenopausal women, are estrogen-independent, histologically higher grade tumors (mostly serous

carcinoma, clear cell carcinoma, and other nonendometrioid histologic types), and present at a higher stage of disease with a higher incidence of metastasis at time of diagnosis.8 Type I endometrial carcinomas are usually preceded by endometrial hyperplasia, whereas type II endometrial carcinomas are not associated with hyperplasia. The molecular pathways have also been documented to be different; type I endometrial carcinomas demonstrate mutations in the KRAS proto-oncogene and PTEN tumor suppressor gene and microsatellite instability, whereas type II endometrial carcinomas have been shown to have p53 mutations with rarely documented microsatellite instability or KRAS or PTEN mutations (see Chapters 7 and 8 and Table 7-1).8,9

carcinoma, clear cell carcinoma, and other nonendometrioid histologic types), and present at a higher stage of disease with a higher incidence of metastasis at time of diagnosis.8 Type I endometrial carcinomas are usually preceded by endometrial hyperplasia, whereas type II endometrial carcinomas are not associated with hyperplasia. The molecular pathways have also been documented to be different; type I endometrial carcinomas demonstrate mutations in the KRAS proto-oncogene and PTEN tumor suppressor gene and microsatellite instability, whereas type II endometrial carcinomas have been shown to have p53 mutations with rarely documented microsatellite instability or KRAS or PTEN mutations (see Chapters 7 and 8 and Table 7-1).8,9

Table 2-1 Epidemiology of Endometrial Carcinoma | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Mass screening for endometrial carcinoma has not been advocated or found to be cost effective.10,11 Most patients present with postmenopausal bleeding and seek medical evaluation, with 10% of patients diagnosed with malignancy upon further investigation. As a result of early investigation and detection, 70% to 75% of patients have surgical stage I disease.12,13

Excess or unopposed estrogen, either from exogenous (e.g., hormone replacement therapy [HRT], tamoxifen, oral contraceptives) or endogenous sources (e.g., obesity, polycystic ovary syndrome, tumors secreting estrogen such as ovarian granulosa cell tumors), increases the

risk of developing endometrial adenocarcinoma.14 Unopposed exogenous hormones were demonstrated to have variable risk depending on age of the patient, perimenopausal or postmenopausal status, and whether the serum levels measured represented high estrone and albumin-bound estradiol, which have been associated with increased risk. However, high levels of serum total, free, and albumin-bound estradiol were unrelated to increased risk.14 An elevated level of androstenedione was also cited as a risk factor in both perimenopausal and postmenopausal women; however, the risk factor associated with obesity was not affected by adjustment for hormones.15,16 Risk associated with unopposed estrogen was decreased by addition of progestin to HRT, use of oral contraceptives, and smoking.15,16,17,18,19 and 20 It was found that women who took combined oral contraceptives (“the pill”) for at least 1 year had a 40% to 50% reduced risk of endometrial carcinoma and were “protected” for up to 15 years after discontinuing the pill.16,21 Postmenopausal women who were prescribed a combined estrogen-progesterone HRT regimen also had a decreased risk of endometrial carcinoma.21

risk of developing endometrial adenocarcinoma.14 Unopposed exogenous hormones were demonstrated to have variable risk depending on age of the patient, perimenopausal or postmenopausal status, and whether the serum levels measured represented high estrone and albumin-bound estradiol, which have been associated with increased risk. However, high levels of serum total, free, and albumin-bound estradiol were unrelated to increased risk.14 An elevated level of androstenedione was also cited as a risk factor in both perimenopausal and postmenopausal women; however, the risk factor associated with obesity was not affected by adjustment for hormones.15,16 Risk associated with unopposed estrogen was decreased by addition of progestin to HRT, use of oral contraceptives, and smoking.15,16,17,18,19 and 20 It was found that women who took combined oral contraceptives (“the pill”) for at least 1 year had a 40% to 50% reduced risk of endometrial carcinoma and were “protected” for up to 15 years after discontinuing the pill.16,21 Postmenopausal women who were prescribed a combined estrogen-progesterone HRT regimen also had a decreased risk of endometrial carcinoma.21

Table 2-2 Comparison between Types I and II Endometrial Carcinoma | ||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Tamoxifen is a selective nonsteroidal receptor modulator that blocks estrogen receptors by competing for the same site as estrogen. However, tamoxifen shows “mixed” function in that in reproductive, perimenopausal women, it demonstrates an estrogenic effect, whereas in postmenopausal women, it demonstrates an antiestrogenic effect. As a result of the “dual personality” of tamoxifen, controversy exists as to its usage, with some studies showing greatly increased risk for endometrial carcinoma and high-grade endometrial carcinomas, whereas other studies have found no significant increased risk.22,23 and 24

Additional well-defined risk factors for developing endometrial carcinoma are obesity, nulliparity, fat-rich diet adding to weight gain, diabetes, hypertension, and early menarche/late menopause. Obesity has been shown to increase the relative risk for endometrial adenocarcinoma 3-fold in women who are 20 to 50 lb overweight and more than 10-fold in women who are ≥50 lb overweight. Increased relative risk was due to increased conversion of androstenedione to estrogen and increased unopposed estrogen in fatty tissue due to increased aromatization of androgens to estradiol.18,25 Nulliparity, like polycystic ovary syndrome, is thought to increase unopposed estrogen as a result of anovulatory cycles and chronic anovulation. Early menarche and late menopause are considered risk factors because patients are exposed to estrogen for a longer period than women with late menarche and early menopause.

Patients with both type 1 and type 2 diabetes are at a twofold increased risk for developing endometrial adenocarcinoma compared with women without diabetes. This increased risk was independent of other risk factors such as obesity.18,

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree