Ovarian Cancer

INTRODUCTION

Ovarian cancer remains the most lethal of gynecologic malignancies in developed countries. Initial management is aimed at maximal cytoreduc-tion by surgery either before or after chemotherapy. Sequential palliative chemotherapy has enabled women to live with recurrent disease for years before suffering and dying with bowel obstruction. Despite advances, effective screening and cure remains elusive for most women.

INCIDENCE

Epithelial cancer of the ovary is the fifth most common tumor of women in the United States after cancer of the breast, colon, lung, and endometrium. It is the most lethal gynecologic malignancy, with approximately 22,240 cases and 14,030 deaths each year (1, 2). One in 70 of American women will develop ovarian cancer sometime during their lifetime. In premenopausal women ovarian cancer is uncommon and found in less than 5% of adnexal masses; indeed, only 30% of adnexal masses are malignant in postmeno-pausal women.

EPIDEMIOLOGY OF EPITHELIAL OVARIAN CANCER

The majority of ovarian cancer presents in postmenopausal women with only 10%-15% of cancers occurring in premenopausal patients. Median age at diagnosis is reported between 60 and 65 years. Possible risk factors identified in case controlled studies include white race, nulliparity, infertility, high fat diet, lactose, paracetamol, and asbestos contaminated talc. Oral contraceptives, pregnancy, tubal ligation, and lactation reduce the risk. The association with early menarche, late menopause, and nulliparity suggests that uninterrupted “incessant” ovulation may predispose to malignancy. The oral contraceptive pill may offer some protective benefit in preventing ovarian cancer in high-risk populations. However, hormone replacement therapy appears to double the risk of death from ovarian cancer. Initial reports of increased risks from fertility drugs have not been confirmed.

FAMILIAL OVARIAN CANCER

The vast majority of ovarian cancer is sporadic. However, a family history of ovarian cancer increases the risk of developing ovarian cancer two- to threefold, and it is estimated that 5%-15% of all epithelial ovarian cancer cases result from inherited predisposition. Approximately 75% of these families are linked to the breast ovarian cancer syndrome with loss of function of the tumor suppressor genes BRCA1 and BRCA2, involved in DNA repair, and inherited in an autosomally dominant fashion. Hereditary breast-ovarian cancer syndrome (HBOC) accounts for 65%-75% of all hereditary ovarian cancer cases, and is defined variably but typically with at least three cases of early onset (<60 years) breast or ovarian cancer. Mutations in BRCA1 (located on chromosome 17q) and BRCA2 (13q) are associated with a 40%-60% life-time risk of ovarian cancer. The founder mutations 185delAG, and 5382insC in BRCA1, and 6174delT in BRCA2 are present in 2.5% of Ashkenazi women.

Hereditary non-polyposis colon cancer syndrome (HNPCC, Lynch syndrome [type II]) results from mismatch repair (MSH2, MLH1, and PMS2) gene defects, low penetrance allele, and modifier gene defects. The American founder mutation is deletion of exons 1-6 of MSH2. HNPCC accounts for approximately 10%-15% of all hereditary ovarian cancer cases. A diagnosis of HNPCC can be made using the Amsterdam Criteria (colon cancer diagnosis in >3 relatives, one of whom is a first-degree relative of the other two, and one diagnosis before age 50 years). The risk of developing ovarian cancer associated with HNPCC appears to be associated with an approximately 3.7-fold increase in lifetime risk of developing ovarian cancer. The inherited predisposition syndromes are summarized in Table 54-1.

Women from high-risk families should have genetic counseling and gene testing. At the present time a similar number of women elect biannual pelvic examinations, transvaginal ultrasound, and CA125 with no proven effect on mortality, as we have a prophylactic risk reducing salpingo-oophorectomy (RRSO), which reduces the lifetime risk of ovarian cancer by 95% (3).

BIOLOGY

Although commonly termed “epithelial,” the embryologic origin of ovarian cancer is mesodermal, from the peritoneal surface of the ovary. Previously, subepithelial inclusion cysts that form after ovulation were thought to be the initial focus of dyplastic change, but compelling evidence points to the fimbria of the fallopian tube as the origin of perhaps 50% of tumors. Primary peritoneal and fallopian tube carcinomas (5%) are rare, and behave and are treated in an identical fashion.

Tumor cells predominantly spread transcelomically to the pelvic structures, exfoliating and following the circulation of the peritoneal fluid throughout the abdomen. Cells also metastasize by lymphatic and hema-togenous routes. Extraperitoneal metastases are rare, but with increasing number of patients living for a protracted time, up to two-fifths of patients will develop metastases in the liver, lung, or the central nervous system during the later stages of their disease.

The majority of epithelial cancers are serous or papillary with a similar appearance to the lining of the fallopian tube (4, 5). Endometrioid carcinoma is associated with synchronous endometrial carcinoma and endome-triosis, and therefore more commonly present early, and have a better prognosis. Clear cell tumors have a particularly poor prognosis, are commonly associated with thromboses, and have distinct genetics that link the disease with other clear cell tumors. Mucinous tumors are more commonly bilateral and can be associated with pseudomyxoma peritonei and mucocele of the appendix. Brenner’s tumor has a histologic pattern similar to transitional cell carcinoma. Molecular evidence has confirmed that carcinosarcomas, previously called malignant mixed Mullerian tumors have a clonal proliferation of the epithelial element rather than being collision tumors and are treated as epithelial cancers. In women under the age of 40 years, but rarely in older patients, 60%-70% of non-benign ovarian neoplasms are borderline tumors, a neoplasm that has distinctly malignant cytological features without invasion. Ovarian tumor pathology is summarized in Table 54-2.

NON-EPITHELIAL OVARIAN MALIGNANCIES

Non-epithelial ovarian cancer accounts for <10% of ovarian tumors. The commonest of these, germ cell tumors represent almost 70% of ovarian tumors in the first two decades of life, with one-third of these being malignant. These rare tumors disseminate early and the doubling time of the tumor can be very short. The tumor markers βHCG and αFP are important in the treatment and surveillance of germ cell tumors. Dysgerminoma, essentially the female equivalent of testicular seminoma, is exquisitely sensitive to platinum, and this is now favored over the traditional treatment of radiotherapy. Teratoma is probably most effectively treated with combination platinum-based chemotherapy such as BEP (bleomycin, etoposide, and cisplatin) and surgical removal of residual masses. Yolk sac, embryonal, and choriocarcinoma subtypes are rarer, curable, and require specialized care.

Sex-cord-stromal tumors account for even fewer ovarian malignancies. Granulosa cell tumors are typically relatively low grade, secrete estrogen and in juveniles, tumors may be associated with pseudo-precocity. The tumors secrete estradiol, Mullerian inhibiting substance, and dimeric inhibin, which serve as tumor markers. Sertoli-Leydig tumors are associated with the production of androgens. Thecomas and fibromas are rare and nonfunctional tumors.

EPITHELIAL OVARIAN MALIGNANCIES

DIAGNOSIS

DIAGNOSIS

The presentation of ovarian cancer is typically subtle, persistent (>2 weeks) abdominal or pelvic pain; bloating, nausea, change in bowel habit, as well as urinary and constitutional symptoms are typical of peritoneal involvement by advanced disease while early stage ovarian cancer is generally asymptomatic (Table 54-3). Unfortunately, most symptomatic women do not have a prompt diagnosis, and indeed it is not uncommon for these women to be misdiagnosed with irritable bowel syndrome, hiatal hernia, diverticu-losis, or endometriosis. Pelvic examination remains an essential part of the examination of women complaining of abdominal symptoms.

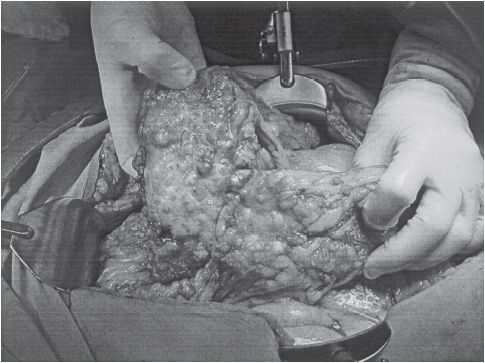

The diagnosis and initial management of ovarian cancer is surgical (Figure 54-1). Premenopausal women with a smooth, unilateral, mobile, cystic adnexal masses up to 8 cm can be managed conservatively with the use of oral contraceptives and serial ultrasound, typically performed at 6 weeks and at a different time of the menstrual cycle, as luteal cysts are common. In postmenopausal women, cystic masses larger than 5 cm in diameter warrant a tissue diagnosis. In postmenopausal women with a CA125 greater than 35 U/ml, adnexal masses are malignant in 80% of cases, although this should not be confused with the finding of a raised CA125 in an asymptomatic postmenopausal woman, as perhaps only 1 in 7 will have ovarian cancer. Occasionally there is uncertainty about the site of the primary and colonoscopy and mammography are appropriate. As early disease is typically asymptomatic, over 75% of tumors present as advanced stage disease (International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics [FIGO]) stage III/IV) (Table 54-4).

Figure 54-1 Advanced ovarian cancer. (Courtesy of Dr. Arlan Fuller.)

The surface glycoprotein CA125 (gene MUC-16) is found at elevated levels in the blood of >80% of patients with epithelial ovarian cancer (abnormal >35 u/ml) (6). CA125 is not useful in screening for occult carcinoma but can be used as a tumor marker. Human epididymis protein 4 (HE4) is another marker elevated in ovarian cancer and when both markers are elevated, adnexal masses are more often malignant. High levels of both markers are associated with disease bulk. Changes in levels correlate with response to therapy or disease progression. The OVA1TM diagnostic is the first FDA-approved blood test to evaluate the likelihood that an ovarian mass is malignant using 5 tumor markers including CA125.

The differential diagnosis of adnexal masses includes simple hemorrhagic physiologic cysts (follicular or corpus luteal); endometrioma; theca luteal cysts; benign, malignant, or metastatic tumors; and extraovarian masses such as paraovarian or peritoneal cysts and pedunculated fibroids, extopic pregnancy, hydrosalpinx, tuboovarian, diverticular, or appendiceal abscesses.

SCREENING

Screening for ovarian cancer is an attractive proposition because of the significant morbidity and mortality associated with advanced disease, the availability of apparently sensitive and specific diagnostic tests (ultrasound and CA125), and the better outcome for patients with early-stage disease. However, there is no evidence at the present time that screening improves survival. The serum marker CA125 has been shown to be elevated in only 50% of patients with stage I disease, but in 90% of stage II-IV ovarian cancers. CA125 has a sensitivity of 20%-58% and a specificity of 97%-99%. With a 1/70 lifetime risk, ovarian cancer is present in 1/2000 postmenopausal women and therefore the false-positive rate (1%-3%) for CA125 is unacceptably high, given the morbidity of laparotomy. In the largest study reported to date in 21,935 UK postmenopausal healthy women, the death rate was apparently halved by screening (18 of 10,977 vs. 9 of 10,958). However, this was not statistically significant (p = 0.083), and the massive U.S. study, Prostate, Lung, Colorectal, and Ovary Cancer Screening Trial (PLCO), in 150,000 subjects failed to confirm a survival advantage, with a 15% serious complication rate from laparotomy (7). There continues to be speculation about whether the sensitivity of screening can be improved by the use of a panel of markers such as HE-4, ROCA (Risk of Ovarian Cancer Algorithm), which evaluates change in CA125 over time, or proteinomics. At the present time, screening is only recommended in high-risk populations (+ve family history or BRCA carriers), where prophylactic surgery has a far greater impact on the risk.

MANAGEMENT OF EARLY STAGE OVARIAN CANCER

Approximately 2000-3000 patients a year in the United States will have disease confined to pelvis. While this group accounts for only 15% of ovarian cancer cases, more than half of all cured patients come from this group. Adequate staging requires that a surgeon with subspeciality expertise perform an exploratory laparotomy, total abdominal hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, omentectomy, careful examination of the peritoneal surfaces of the liver, diaphragm, pericolic gutters, and pelvic sidewalls with multiple biopsies and sampling of ascitic fluid and peritoneal washings with para-aortic and pelvic lymph node sampling. Patients diagnosed with apparently early-stage ovarian cancer without adequate staging should undergo reexploration for definitive staging.

The overall 5-year survival of patients with apparent stage I epithelial cancer was about 60% in earlier reports. With accurate staging, and migration of patients with clinically occult nodal or omental metastases to stage III, survival of stage I patients is now commonly reported as >90%. Approximately 30%-46% of cancers that appear to be confined to the pelvis (stages I and II) have occult metastatic disease in the upper abdomen or lymph nodes (stage III). In patients with stage IA and IB disease of low grade (well differentiated), no adjuvant treatment is warranted. For all other patients with high-risk histology or grade, adjuvant treatment is recommended with platinum-based chemotherapy based on Gynecologic Oncology Group (GOG-95), International Collaboration in Ovarian Neoplasia (ICON I), and the European Organization for the Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTCs) ACTION study (8).

GOG-157 compared 3 with 6 cycles of carboplatin and paclitaxel in early-stage disease. While more cycles were associated with more toxicity, there was a survival advantage in serous tumors and so most patients still receive 6 cycles of chemotherapy if tolerated.

MANAGEMENT OF ADVANCED STAGE OVARIAN CANCER

The principle of therapy for patients with advanced ovarian cancer is to cytoreduce (debulk) with surgery and chemotherapy to a state of minimal residual disease. For some patients this will translate into cure, but for the majority of patients, it delays symptomatic relapse. Current standard of care has been defined as cytoreductive surgery and 6 cycles of a taxane with either cisplatin or carboplatin chemotherapy. Five-year survival rates for patients treated with platinum-based regimens are approximately 20%-40%. Figure 54-2 illustrates a treatment algorithm for advanced ovarian cancer.

FIGURE 54-2 Treatment algorithm for ovarian cancer.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree