Step 1

Surgical Anatomy

- ♦

The adrenal gland is composed of a cortex and medulla that have different embryologic origins.

- ▴

The adrenal cortex arises from the coelomic mesoderm between the fourth and sixth weeks of gestation. Although the adrenal cortex is composed initially of an inner zone and a large outer fetal zone, this fetal zone involutes late in gestation and in the early postnatal period, leaving only a thin cortical layer in the mature adrenal gland.

- ▴

The adrenal medulla is derived from cells of the neural crest that migrate to the adrenal cortex. The neural crest also forms the sympathetic nervous system and ganglia. Because of this, cells that are derived from the neural crest (often referred to as chromaffin cells because they contain cytoplasmic granules with an affinity for certain salts of chromic acid) may also develop in extra-adrenal sites, most commonly in the para-adrenal and para-aortic regions. The single most common site where extra-adrenal chromaffin tissue develops is the organ of Zuckerkandl, located adjacent to the aorta, at or just proximal to its bifurcation, near the origin of the inferior mesenteric artery.

- ▴

- ♦

The adrenal cortex produces glucocorticoids (cortisol), mineralocorticoids (aldosterone), and sex steroids (largely androgens). Adrenocortical carcinoma (ACC) can produce all three types of hormones in superphysiologic amounts. The most common hormonal excess syndrome seen in patients with ACC is Cushing’s syndrome due to cortisol overproduction by the primary adrenal cancer. The adrenal medulla, similar to all chromaffin cells, produces epinephrine and norepinephrine. Malignant tumors of the adrenal medulla (malignant pheochromocytoma) are uncommon and will not be discussed in this chapter, which focuses on ACC.

- ♦

The adrenal glands are paired structures that have a pyramidal shape and are located in the retroperitoneum along the superior medial aspect of each kidney. The normal adult adrenal gland weighs approximately 4 to 5 grams, and measures approximately 4 to 5 cm vertically, 3 cm transversely, and 1 cm in the anteroposterior plane. The adrenal glands are highly vascular and of soft consistency, being completely surrounded by perirenal fat.

- ♦

On cut sections, the adrenal gland has two distinct layers: a thin (1 to 2 mm), bright yellow cortex that envelops an even thinner layer of dark reddish gray tissue, the adrenal medulla. The medulla is soft and constitutes only approximately 10% to 20% of the total weight of the adrenal gland. The bright yellow color of the adrenal cortex helps to distinguish it from the surrounding retroperitoneal fat and adjacent liver (on the right) and pancreas (on the left).

- ♦

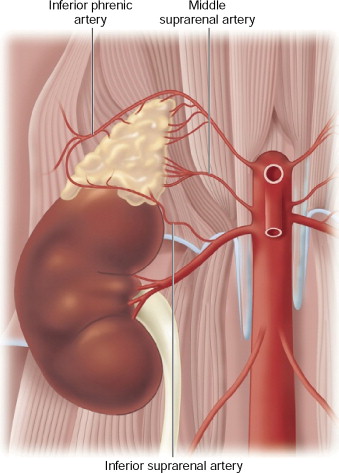

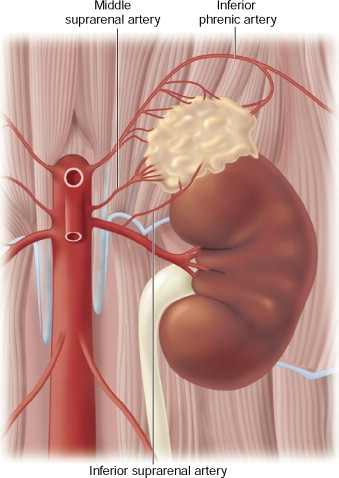

The arterial blood supply to the adrenal glands comes from branches of the inferior phrenic arteries, the renal artery, and directly from the aorta. See Figures 13-1 and 13-2 for illustrations of the anatomy of the right and left adrenal glands, respectively. The nutrient arteries coalesce and anastomose to form a capsular arterial plexus that sends capillaries coursing through the cortical cells. These capillaries combine to form a venous portal system that drains into the adrenal medulla. There, the vessels come together to join the central adrenal vein. This venous portal system supplies the adrenal medullary tissue with a high concentration of adrenal steroids. Additionally, the adrenal medulla is supplied by arteriae medullae, which penetrate directly into the substance of the adrenal medulla.

Figure 13-1

Figure 13-2

- ♦

Although some small veins drain from the surface of the adrenal cortex, most arterial blood flows from the capsular plexus, through the cortex, into the medulla, and out of the central vein. The right adrenal vein is short and wide; it exits the gland and immediately enters the posterolateral aspect of the inferior vena cava. The left adrenal vein exits anteriorly and usually drains into the left renal vein, although it occasionally enters the inferior vena cava directly. As a result, it is easier to control the adrenal vein on the left than on the right; as the size of the adrenal tumor increases, vascular control of the right adrenal vein can become more difficult.

Step 2

Preoperative Considerations

- ♦

In the absence of a hormonal excess syndrome patients should be evaluated in a standard manner, with attention paid to performance status, end-organ function, and cardiopulmonary risk as would be done before any major abdominal or thoracic operation.

- ♦

In the presence of Cushing’s syndrome one may want to attempt control of the hormonal syndrome (with metyrapone, for example) before laparotomy.

- ♦

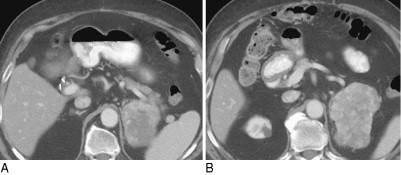

Very rarely, one may see aldosterone secretion causing hypokalemia and hypertension; this usually responds to selective aldosterone inhibition with spironolactone (Aldactone) or eplerenone (Inspra), if needed, before surgery. Figure 13-3 presents CT images of a large 9.6 cm left adrenal cortical carcinoma in an 80-year-old man who presented with profound hypertension and hypokalemia. There was biochemical evidence of hyperaldosteronism and normal serum levels of ACTH and cortisol (although his cortisol failed to suppress to a low-dose overnight dexamethasone suppression test).

Figure 13-3

- ♦

The day before surgery we usually have the patient perform a mechanical bowel preparation; the operation is routinely performed with combined epidural and general anesthesia. Central venous access and standard arterial monitoring are used.

- ♦

Computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is performed preoperatively to assess the local resectability of the primary tumor and assess for the presence of liver and lung metastases (when the diagnosis is thought to be ACC).

- ♦

On the right, evidence of local unresectability would include the following:

- ▴

Complete occlusion of the inferior vena cava (IVC) with involvement of the left renal vein and hepatic veins

- ▴

Extension into the porta hepatis with portal vein and hepatic artery encasement

- ▴

Encasement of the abdominal aorta

- ▴

The need for right nephrectomy in a patient with inadequate renal function on the left.

- ▴

- ♦

On the left, evidence of local unresectability would include the following:

- ▴

Abutment or encasement of the celiac axis

- ▴

Encasement of the abdominal aorta

- ▴

The need for left nephrectomy in a patient with inadequate renal function on the right. In addition, in general, we would not consider immediate surgery to remove the primary tumor in the setting of extra-adrenal distant metastatic disease.

- ▴

- ♦

When dealing with a presumed (yet biopsy unproven) ACC, one should consider a biopsy only if planning neoadjuvant therapy (chemotherapy, chemoembolization), or when the diagnosis is most likely an adrenal metastasis in a patient with a known history of a previous cancer and a clinical presentation consistent with an adrenal metastasis (where the diagnosis of metastasis would result in a plan for initial systemic therapy rather than surgery). Therefore, percutaneous biopsy of an adrenal neoplasm should be a very infrequent event.

Step 3

Operative Steps

Right Adrenalectomy

- ♦

Three main technical issues must be emphasized when performing right adrenalectomy.

- ▴

Preoperative planning for the optimal skin incision, which depends on the size of the tumor (and the degree of liver compression between tumor and diaphragm) and the anticipated need for liver resection

- ▴

The importance of performing a complete gross resection of the tumor, which may require right nephrectomy and nonanatomic liver resection or right hepatic lobectomy

- ▴

Management of the right adrenal vein and the retrocaval collateral vessels.

- ▴

- ♦

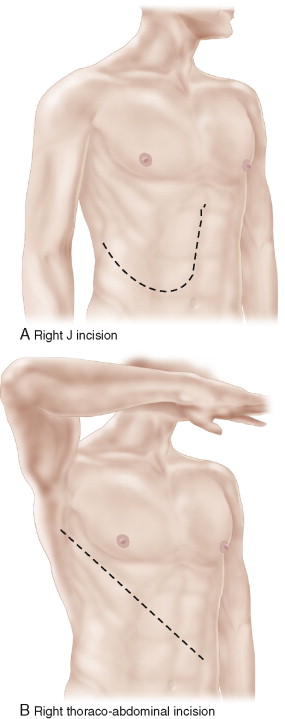

The abdomen can be opened with a midline incision, a J (Makuuchi) incision, or a right thoraco-abdominal incision ( Fig. 13-4A-C ). Removal of the right adrenal gland through a transabdominal approach requires that the liver be completely mobilized (or that the liver be divided before mobilization, as described below). Attempted removal of the right adrenal gland without mobilization of the right lobe of the liver, to allow complete exposure of the infrahepatic IVC, is a mistake. Figure 13-5 presents CT images of recurrent ACC secondary to tumor spillage at the time of adrenalectomy. Figure 13-5A shows diffuse carcinomatosis in a 46-year-old woman following a laparoscopic adrenalectomy during which the tumor was fractured. In Figure 13-5B , there is a local recurrence in the right adrenal bed following an open adrenalectomy in which the liver was not fully mobilized to allow adequate exposure for complete resection. This limited exposure to the cephalad extent of the tumor likely contributed to an incomplete gross resection. The initial postoperative CT scan (left panel) was interpreted as equivocal for recurrence, but less than 3 months later it was clear that this represented tumor recurrence in the bed of the incompletely resected adrenal gland (right panel). In Figure 13-5C , a recurrence in the left flank due to tumor implantation following a flank approach to a 4 cm ACC is evident.